Development Issues No. 9: Low growth with limited policy options? Secular Stagnation – Causes, Consequences and Cures

The Development Policy and Analysis Division at DESA has prepared a series of policy notes to review current trends in the global economy with the intention of stirring debate about the imperative to create an enabling international environment for sustainable development. This note describes the debate on the macroeconomic difficulties facing developed countries, which will affect the enabling environment for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Recent growth trends in developed economies – stuck in secular stagnation?

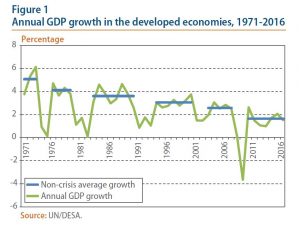

The recovery of the world economy from what is now commonly referred to as the Great Recession of 2008/09 has been unexpectedly weak. From 2011-16, world gross product growth averaged only 2.5 per cent per year, a full percentage point below the rate recorded in the pre-crisis period of 2000-07. Developed economies, in particular, have seen a slow recovery with average annual GDP growth of just 1.5 per cent from 2011-16, down from 2.5 per cent in 2000-07 (figure 1).

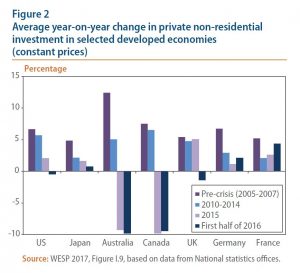

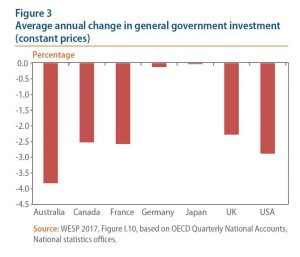

Employment and labour participation have also recovered more slowly than after previous recessions. This subdued economic environment is projected to persist over the next few years, according to the World Economic Situation and Prospects (WESP) 2017. The weakness in growth coincides with a slowdown in private and public investment in developed economies (figures 2 and 3). Weak investment not only weighs on aggregate demand in the short run, but also reduces growth in productivity and potential output in the medium- to long-run.

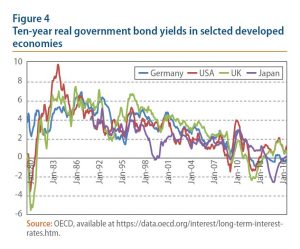

The weak recovery in developed economies has also been marked by a continuation of the long-term decline in interest rates, persistent below-target inflation, and stagnant wages for large segments of the workforce. Real long-term interest rates have been on a steady downward trend since the early 1980s (figure 4). In 2016, 10-year nominal government bond yields turned negative in Germany and Japan and remained remarkably low in most other developed economies.2 Such low bond yields suggest that the market expects low inflation and low real interest rates to persist in the medium-run. Wages have been affected by declines in labour shares and by disproportionate gains of high wage earners.

Aggressive and persistent monetary easing by central banks has brought nominal interest rates close to the zero lower bound. With future inflation expected to remain low, there is little room left for monetary policy to add further stimulus. The question of whether developed economies are stuck with low-growth, low investment, low inflation and low interest rates—and how such a scenario could possibly be averted—has triggered a fruitful debate among eminent economists. Bradford DeLong (2016) recently called this “the most important policy-relevant debate in economics since…the 1930s”.

Aggressive and persistent monetary easing by central banks has brought nominal interest rates close to the zero lower bound. With future inflation expected to remain low, there is little room left for monetary policy to add further stimulus. The question of whether developed economies are stuck with low-growth, low investment, low inflation and low interest rates—and how such a scenario could possibly be averted—has triggered a fruitful debate among eminent economists. Bradford DeLong (2016) recently called this “the most important policy-relevant debate in economics since…the 1930s”.

In fact, the importance of this debate can hardly be overstated as the economic performance of developed countries is a key determinant for an enabling environment of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Long term stagnation in developed countries could act as a major headwind for growth and poverty reduction in developing countries, create instability in trade and financial markets, and reduce the amounts of investment and concessional finance available, including for the Least Developed Countries. Increased trade and financial integration of the world economy has resulted in a rapid transmission of macroeconomic shocks across borders. The financial crisis of 2008/09 has illustrated this global interdependence and interconnectedness, refuting the idea that developing countries have “decoupled” from developed economies. Moreover, the post-crisis experience, in particular the use of unconventional monetary policies by major central banks, has demonstrated how strongly the macroeconomic conditions and the policy space of developing countries depend on the measures implemented in developed economies.

Long term stagnation or short-term disequilibrium?

The most comprehensive account of the current situation in developed countries is arguably provided by the “secular stagnation” hypothesis.3 According to this explanation, the economies face a lasting excess of desired savings over desired investment, which weakens aggregate demand and puts downward pressure on the real interest rate. In other words, the rate of real interest that is required for the economy to be at full employment (natural real interest rate) is too low and cannot be achieved with conventional monetary policies. This savings-investment imbalance results in the observed low interest rates, below target inflation and sluggish output growth in developed economies.

The secular stagnation hypothesis provides an intuitive and compelling account of the current economic malaise in developed countries and is largely consistent with recent macroeconomic developments. A number of additional explanations exist for the observed trends. Some are consistent with the secular stagnation view and underscore the long-term nature of the underlying problem. Other explanations provide a less pessimistic assessment, characterizing the current weaknesses in developed economies as largely temporary or cyclical. Depending on the concrete diagnosis of the fundamental causes, the studies reach very different conclusions about the necessary policy responses.

Under-consumption

John A. Hobson argued in 1902 that chronic under-consumption and excessive savings can result from a high concentration of wealth and high levels of inequality. Greater consumption and investment would thus be needed to offset the lack of domestic demand and boost output. This under-consumption explanation has re-emerged in light of rising inequality.

Global savings glut

According to Ben Bernanke (2005), the savings-investment imbalance is essentially the result of excessive savings in emerging markets in search for safe, liquid assets. Households and governments accumulate savings and reserves as insurance against financial shocks. Without sufficient investment opportunities in these markets, this excess of desired savings over desired investment puts downward pressure on real interest rates in developed countries. The flow of savings also leads to currency appreciation in developed countries, weakening their net exports and growth.

Technological and demographic stagnation

Alvin Hansen suggested in 1939 that technological and demographic stagnation negatively affected the return on investment, pushing down desired investment demand and resulting in secular stagnation. Robert Gordon (2015) applied this argument to the current context, explaining that slower growth in potential output results from the combination of slow productivity growth, slower population growth and a decline in the labour force participation rate. According to Gordon, the productivity slowdown can be primarily explained by diminishing returns to innovation, in particular as a result of the information and communication technology revolution.

Decline in the relative price of investment goods

As documented by Karabarbounis and Neiman (2014), developed economies have seen a significant decline in the price of investment relative to consumption goods over the past few decades. This decline accelerated in the early 1980s and is generally attributed to advances in information technology and the computer age. Thwaites (2015) shows that a fall in the relative price of investment goods could lead to an increase in the real capital-output ratio, which lowers the marginal product of capital and results in lower real interest rates.

Debt overhang

Kenneth Rogoff (2015) sees the current period of slower growth as the direct result of the residual excessive debt from the global financial crisis and the Great Recession. Governments and firms in developed economies face the need to reduce debt, which increases net savings and decreases investment and growth. Rogoff argues that this debt overhang has also undermined the ability of financial markets to function properly and to properly match savings and investment.

Liquidity trap and the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates

Paul Krugman (2013) explains the current situation as a typical Keynesian liquidity trap. Because the nominal interest rate is at or near the zero lower bound, and given low inflation expectations, the monetary authority must commit to higher inflation targets and negative real interest rates to stimulate investment. One concrete target is to double the inflation target from 2 per cent to 4 per cent.

Policy options to escape secular stagnation

All of the explanations presented above provide insights into the reasons for continued sluggish growth, below target inflation, and low interest rates. Each of the explanations, however, addresses only part of a more complex and overarching problem. Escaping the trap of secular stagnation and realising a more enabling environment for the Sustainable Development Goals will require interventions that simultaneously address the various factors affecting the excessive supply of savings and weak demand for investment (see for example Teulings and Baldwin, 2014). Some of the factors can be influenced in a relatively short period, such as the imbalance in global capital flows and the decline in demand for investment goods. It will require longer periods to reverse trends in productivity and inequality and counterbalance demographic changes. It is therefore helpful to consider the possible policy options in terms of their short- and long-term effects.

Short term

Policy makers in developed economies have a range of fiscal, monetary, income and industrial policy tools to address the savings-investment imbalance in the short- to medium-run. The effectiveness of individual policy measures depends, however, on the country-specific environment.

On the fiscal side, governments have instruments at their disposal to change both expenditures and revenues. Public investment in infrastructure, education and research and development, combined with private sector incentives in the sustainable energy sector are good examples to boost the demand for investment (see for example Mourougane, 2016). Alternatively, governments can provide tax credits for low-income or liquidityconstrained households to increase the incomes of those with a high marginal propensity to consume.

On the monetary side, the challenge is that central banks need room to reduce real interest rates and boost output in the face of an exceptionally low natural rate of interest. With standard monetary policy being limited by the zero lower bound, central banks have resorted to unconventional monetary policy tools, such as large-scale asset purchases, negative interest rates and forward guidance.4 A recently discussed alternative option is an increase in the official inflation target (from currently 2 per cent to 4 per cent) in order to raise inflationary expectations. This would give the central bank additional room to reduce the real interest rate to its natural rate.

Targeted industrial policies can provide additional support for aggregate demand in the short- to medium-run and help lift the natural rate of interest. Incentives for industries that are heavy consumers of investment goods, for example, can help reverse the decline in the marginal product of capital and put upward pressure on interest rates.

Long term

Reversing the trends in productivity and inequality, and counterbalancing demographic changes will require longer term interventions that need to take into account the linkages and interactions between these secular trends.5

As stated by Paul Krugman in his 1994 book The Age of Diminishing Expectations “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.” In fact, over a longer time period, productivity is the single most important determinant of a country’s level of real income and potential output. Fostering productivity growth must therefore be at the centre of national and international policy agendas as an enabling condition for development. Countries can boost productivity by expanding public and private investment in human capital—including education, child care and on-the job training—and in research and development. New firm level evidence also underscores that the regulatory environment needs to keep up with structural changes in the global economy, such as digitalization, globalization and the rising importance of tacit knowledge (Andrews et al., 2016). Policy efforts should thus be directed towards lowering entry barriers and ensuring the contestability or competiveness of product markets, while facilitating the adjustment of workers to changing conditions.

In virtually all developed economies, income inequality has risen notably over the past few decades. The top-income earners have made strong gains, whereas large segments of the population have seen real incomes stagnate and even fall. High or rapidly rising inequality is increasingly regarded as an obstacle to longterm economic growth. The direct way for Governments to tackle this problem is to intensify their redistributive efforts.6 Larger and more progressive tax and transfer policies can significantly reduce inequality and economic insecurity. Redistributive efforts could also include some combination of means-tested or universal basic income and robust safety nets and health care systems. Redistribution, however, does not address the underlying causes of rising inequality, such as higher skill premium, the disruption in labour markets caused by technological progress and globalization and the decline in the bargaining power of workers. Policy responses must therefore focus on supporting those who have been negatively affected by these trends, for example by assisting workers to acquire new skills and help them find new jobs. Strengthening labour market institutions to better balance negotiating positions, including unionization, can also help increase the labour share of income and reduce inequality (Barkai 2016). Preventing the conditions that give rise to excessive household debt and financial vulnerability is also important to promote long term progress.

Demographic change, in particular population ageing, has weighed on growth in developed economies, most notably in Japan and parts of Europe. While this trend will persist in the coming decades and raise significant challenges, the negative impact on growth can be mitigated through a number of policy measures. Stimulating labour productivity growth, as discussed above, has the largest potential to mitigate the effect of ageing on growth. Governments can promote an expansion of the supply of labour by expanding immigration and raising the participation of women and older persons in the labour force. Policies to ease the outsourcing of jobs and to promote labour-saving technological transformation can help to align the domestic labour demand and supply. Given the political difficulties that come from large changes in labour markets, boosting productivity and the participation of domestic labour is the most viable approach, however.

References

Andrews, Dan, and Chiara Criscuolo and Peter N. Gal (2016). “The Best versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence across Firms and the Role of Public Policy,” OECD Productivity Working Papers 5, OECD Publishing.

Akyüz, Yilmaz (2017), “Inequality, Financialization and Stagnation”, South Centre Research Paper No. 73.

Barkai, Simcha (2016), “Declining Labor and Capital Shares”, mimeo.

Bernanke, Ben S. (2005), “The Global Saving Glut and the U.S. Current Account Deficit,” speech delivered in Sandridge Lecture, Virginia Association of Economists, Richmond, Virginia.

Bradford DeLong, J. (2017), “Three, Four... Many Secular Stagnations!” Grasping Reality with Both Hands.

Eichengreen, Barry (2015), “Secular Stagnation: The Long View.” NBER Working Paper No. 20836

Gordon, Robert (2015). “Secular Stagnation: A Supply-Side View”.

American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 105(5): 54-59 Karabarbounis, Loukas, and Brent Neiman (2014),” The Global Decline of the Labour Share”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2014), 61–103.

Krugman, Paul (1994), “The Age of Diminished Expectations”. The MIT Press.

Krugman, Paul (2013), “Secular Stagnation, Coalmines, Bubbles, and Larry Summers”, The Conscience of a Liberal.

Mourougane, Annabelle (2016), “Can an Increase in Public Investment Sustainably Lift Economic Growth?”. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1351.

Rogoff, Kenneth (2015), “Debt supercycle, not secular stagnation”, VoxEU.org.

Summers, Lawrence H. (2015), “Rethinking Secular Stagnation After Seventeen Months”, document presented in IMF Rethinking Macro III Conference.

Teulings, Coen, and Richard Baldwin, eds. (2014), “Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cures”, London: CEPR.

Thwaites, Gregory (2015),” Why are real interest rates so low? Secular stagnation and the relative price of investment goods.” Bank of England, Staff Working Paper No. 564.

Follow Us