Development Issues No. 8: Global context for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Sustained global economic growth

The Development Policy and Analysis Division at DESA has prepared a series of policy notes to review current trends in the global economy with the intention of stirring debate about the urgent need to create an enabling international environment for sustainable development. This note reviews recent trends in global economic growth and the challenges it poses for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Robust and sustained growth for sustainable development

There is a general consensus that sustained and faster economic expansion is necessary to accelerate the development process in the most vulnerable countries and to rebalance global economic prosperity. As indicated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, sustained economic growth will continue to be an important objective in developing countries, especially in those where extreme poverty is widespread and income per capita remains low. The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 explicitly calls to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. SDG target 8.1 specifies that Least Developed Countries (LDCs) should grow much faster than average: “Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 per cent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries”.

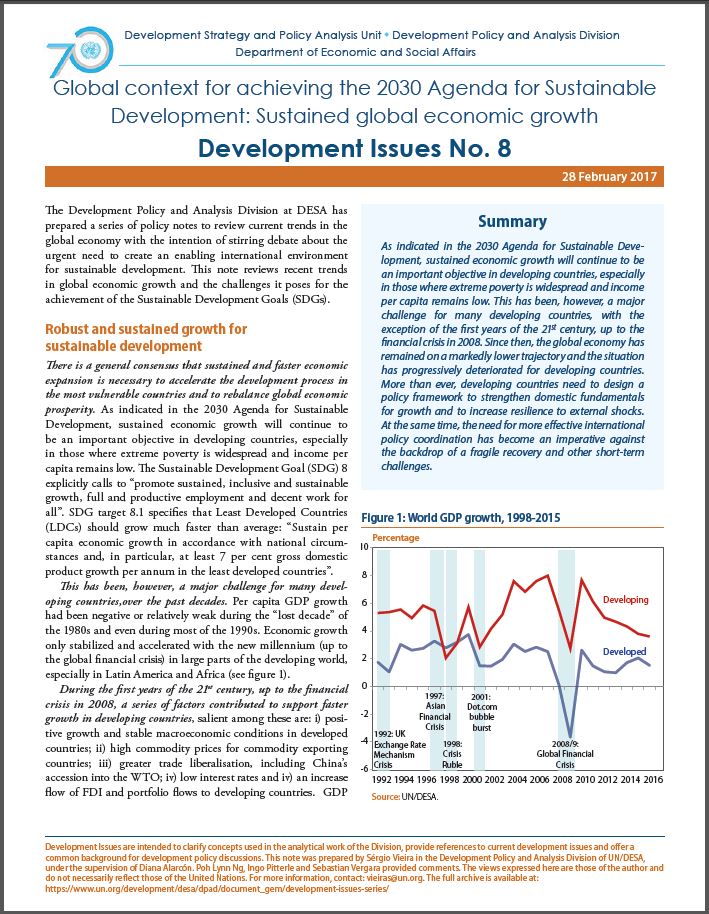

This has been, however, a major challenge for many developing countries,over the past decades. Per capita GDP growth had been negative or relatively weak during the “lost decade” of the 1980s and even during most of the 1990s. Economic growth only stabilized and accelerated with the new millennium (up to the global financial crisis) in large parts of the developing world, especially in Latin America and Africa (see figure 1).

During the first years of the 21st century, up to the financial crisis in 2008, a series of factors contributed to support faster growth in developing countries, salient among these are: i) positive growth and stable macroeconomic conditions in developed countries; ii) high commodity prices for commodity exporting countries; iii) greater trade liberalisation, including China’s accession into the WTO; iv) low interest rates and iv) an increase flow of FDI and portfolio flows to developing countries. GDP

per capita in developing countries grew by 4.4 per cent a year between 2000 and 2008.2 In the least developed countries, GDP growth also accelerated during those years, reaching an average of 6.8 per cent annually or the equivalent of 4.0 per cent growth in GDP per capita. By contrast, growth in developed countries in this time period was 1.7 per cent a year. This growth discrepancy between developed and developing countries helped to increase the latter’s share in global output, from about 20 per cent in 1990 to 37 per cent in 2015 (at constant US dollars).

Faster growth in a greater number of developing countries accelerated income convergence with developed countries. The ratio of per capita income of developing countries to that of developed countries (at purchasing power parity) increased from 16 per cent in the year 2000 to a remarkable 25 per cent in 2014. Prior to 2002, income convergence with developed economies was mainly explained by Asian countries, China in particular. After 2002, this trend was extended to other developing regions, such as Latin America and Africa (see figure 2).

This favourable conjuncture for developing countries was, however, interrupted by the Great Recession in 2008, ending a decade of rapid expansion. The global economy declined markedly in 2009, contracting by 2.5 per cent while developing countries showed resilience even as growth fell well below the pre-crisis years. The difference in performance suggested possible decoupling of the business cycles of developing and developed economies and the idea that emerging economies had developed stronger internal sources of growth. This idea was soon revisited in the aftermath of the financial crisis when it became clear that the business cycles of developed and developing countries were still highly correlated (see figure 1).

This favourable conjuncture for developing countries was, however, interrupted by the Great Recession in 2008, ending a decade of rapid expansion. The global economy declined markedly in 2009, contracting by 2.5 per cent while developing countries showed resilience even as growth fell well below the pre-crisis years. The difference in performance suggested possible decoupling of the business cycles of developing and developed economies and the idea that emerging economies had developed stronger internal sources of growth. This idea was soon revisited in the aftermath of the financial crisis when it became clear that the business cycles of developed and developing countries were still highly correlated (see figure 1).

Since then, the global economy has remained on a markedly lower trajectory and the situation has progressively deteriorated for developing countries. This is explained by the end of the commodity boom cycle, but also by a more challenging and uncertain global environment. The outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area, the policy uncertainty in developed countries, and the growth slowdown in large emerging economies, such as China, Brazil and the Russian Federation are among the major factors affecting negatively the global economic context. There are also a number of internal factors that have constrained growth in developing countries: the persistent vulnerabilities associated with lack of economic diversification and high reliance on commodity exports; the recurrent weather-related shocks; the intensified pressures for fiscal consolidation; and the rising geopolitical tensions and internal political crises.

Looking forward, the prospects for the global economy remain weak and the challenges for developing countries are immense. According to the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2017, the world economy expanded by just 2.2 per cent in 2016, the slowest rate of growth since the Great Recession of 2009. While growth of world gross product is forecast to pick up to 2.7 per cent in 2017 and 2.9 per cent in 2018, this moderate improvement is more an indication of economic stabilization than a signal of a robust and sustained revival of global demand.

Considering this persistent weakness in global growth, the prospects for developing countries remain limited. Developing countries will remain particularly vulnerable to shifts in commodity prices and to instability in international financial markets. Given low commodity prices, mounting fiscal and current account imbalances, as well as policy tightening, growth prospects for many commodity-exporting economies are limited. This has been further compounded by significant exchange rate fluctuations and large capital outflows in many developing regions, especially after the end of the commodity boom cycle and the anticipation of the monetary policy tightening cycle in the United States in mid-2014.

An extended period of weak global growth would pose significant challenges to achieve sustained economic growth in developing countries, but also a number of other sustainable development goals, including poverty eradication. The links between economic growth and other sustainable development goals are complex. There has been ample evidence that economic growth is not a sufficient condition to see progress in human and social development. Complementary policies are also needed to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are translated in human progress and reach the most vulnerable social groups. However, it is also clear that promoting economic growth is a necessary condition to see consistent and sustainable progress in other development dimensions. Thereby, a number of policies should be prioritized, both nationally and internationally, to accelerate economic growth in developing countries.

An improved policy framework is necessary to strengthen domestic fundamentals for growth and to increase resilience to external shocks. Strengthening productivity growth, productive capacity and economic diversification requires increased investments in human capital, infrastructure and technological improvement. Strengthening governance structures is also essential to improve the mobilization of domestic resources and the regulatory framework for the banking system. Policies will need to evolve in response to new challenges and the appropriate combination of policies will vary from country to country, but ultimately the overarching goal should be to strengthen domestic growth and reduce external vulnerabilities.

At the global level, the need for more effective international policy coordination has become an imperative against the backdrop of a fragile recovery and other short-term challenges, such as destabilizing capital outflows and exchange rate volatility in emerging markets. A better mix of policies is needed, moving beyond excessive reliance on monetary policies to support national economies. Effective use of fiscal policies to support demand, output and jobs, as well as to target poverty and inequalities, should remain an overarching priority for enhanced international policy coordination.

Follow Us