23 July 2024

Trade and Development Board

Seventy-first session

Geneva, 16–27 September 2024

Item 8 of the provisional agenda

Report on UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people

Developments in the economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory

Note by the UNCTAD secretariat.

Summary

The thirtieth anniversary of the Oslo Accords coincided with a severe confrontation. Intense Israeli operations in Gaza and restrictions in the West Bank inflicted the greatest damage to the Palestinian economy in recent history.

In Gaza, the military operation decimated the remaining infrastructure and precipitated an unprecedented humanitarian and environmental crisis, as the gross domestic product fell by 81 per cent in the last quarter of 2023 and unemployment soared to 79 per cent. Prior to October 2023, 80 per cent of Gazans depended on international assistance. By the end of the year, multidimensional poverty had affected the entire population.

The West Bank and East Jerusalem were not spared, as violence spread and the occupying Power tightened long-standing restrictions on movement and access. The quarterly gross domestic product shrank by 19 per cent and unemployment reached 32 per cent.

Inflationary pressures combined with increasing unemployment and declining incomes to erode household welfare. The decline in economic activity exceeded the impact of previous confrontations in 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021, on course to surpass the impact of the aftermath of the second intifada.

Settlements continued to expand in 2023 and early 2024. Their growth displaces Palestinians, alters reality on the ground, changes the demographics in East Jerusalem and Area C of the West Bank and hinders a two-State solution.

The success of the Palestinian National Authority in governance and building capable institutions has been widely recognized, as early as in 2011, including by the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations and the World Bank. However, in recent years, the capacity of the Palestinian Government to perform basic functions has been weakened by a lack of resources and recurrent crises. Withholding and deductions by Israel from Palestinian revenues, leakage of fiscal resources and a steep decline in donor aid have contributed to a severe fiscal crisis that poses direct threats to sociopolitical stability and the banking system.

I. An unparalleled shock overwhelms the Palestinian economy

A. From arrested development to large-scale destruction

1. The thirtieth anniversary of the Oslo Accords coincided with the most severe confrontation in recent history and since the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority in 1994. Following the events of 7 October 2023, the occupying Power launched a military operation in Gaza. An intense and sustained military operation has decimated entire neighbourhoods and resulted in high numbers of deaths and the destruction of infrastructure, schools, hospitals, housing units, agricultural assets and energy, water and telecommunications networks. Across the Occupied Palestinian Territory, production processes have been disrupted or decimated, income sources have disappeared, poverty has intensified and expanded, neighbourhoods have been eradicated and communities and towns have been ruined. The operation caused unprecedented humanitarian, environmental and social crises and transformed the region from one experiencing underdevelopment to one facing devastation. The direct damage to the economy, infrastructure and productivity of Gaza continued to accumulate through mid-2024. Repairing the damage will take decades, and the socioeconomic repercussions of the large-scale destruction will be felt for a long time. By early 2024, 82 per cent of private sector establishments in Gaza had been damaged or fully destroyed; and 96 per cent of private sector establishments in the West Bank reported a decline in sales and 42.1 per cent reported a decrease in the total number of employees reporting to work.[1]

2. UNCTAD has assessed the evolution of the economic crisis in Gaza, which took a sharp downturn in 2007, and provided a preliminary assessment of the economic impact of the current confrontation.[2] The report of the Secretary-General to the General Assembly at its seventy-ninth session provides a detailed assessment of the economic impact of the military operation through May 2024.

3. Prior to October 2023, a consensus had emerged that sustainable development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory required lifting the restrictions and closures in Gaza and the removal of all restrictions on movement, trade and investment in the West Bank, as first steps to ending occupation.[3] The performance of the Palestinian economy has been largely determined by measures taken or not taken by the occupying Power and, to a lesser extent, by aid flows that have either mitigated the economic impact of occupation or revealed the impact when they ebbed. In the past few years, UNCTAD and various international organizations have described the state of the Palestinian economy and its prospects as dire. Post-pandemic growth momentum has waned. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth was projected to lag behind population growth and hover at around 2 per cent over the medium term, implying a continuous decline in per capita income for the growing population.[4]

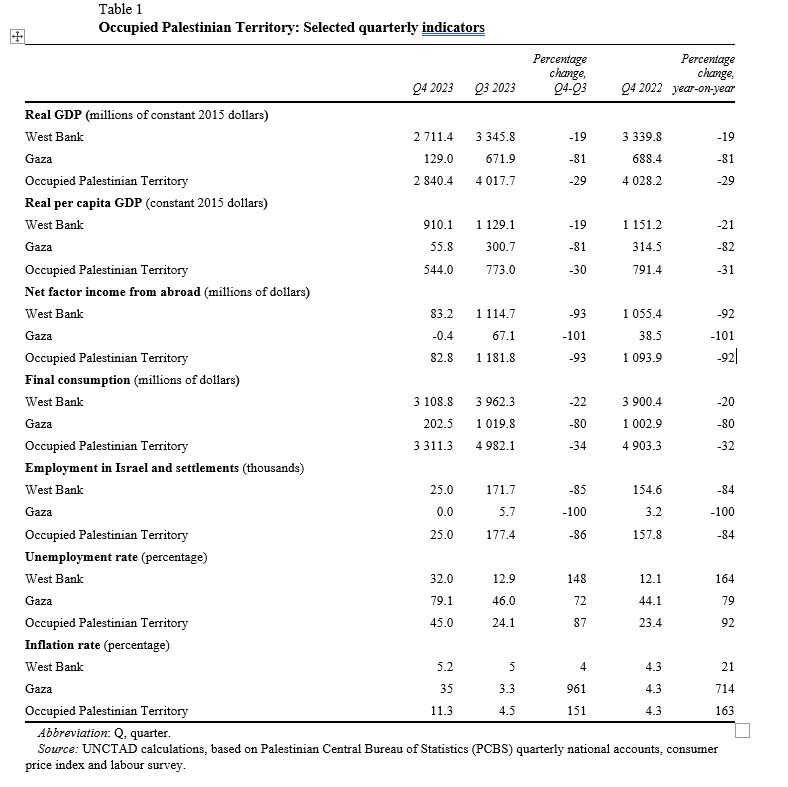

4. Table 1 shows the immediate impact of the latest military operation. All key economic indicators fell steeply in the fourth quarter of 2023 and the first half of 2024, as the economy was affected by the greatest economic shock in recent history. In the first three quarters of 2023, the Palestinian economy grew by 2.8 per cent, compared with in the same period in 2022. However, in the last quarter of 2023 alone, the Palestinian economy shrank by 30 per cent, compared with in the fourth quarter of 2022. This reversal led to a 5.5 per cent contraction in annual GDP and an 8 per cent decline in GDP per capita; one of the deepest slumps in recent history. In the West Bank, 4 per cent GDP growth in the first three quarters of 2023 was followed by a 19 per cent decrease in the last quarter. Consequently, annual GDP contracted by 1.9 per cent; and GDP per capita, by 4.5 per cent. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the economy of Gaza shrank by 81 per cent; the most severe contraction in recent history. In 2023, GDP in Gaza contracted by 22.6 per cent, leading to a decline of 24.5 per cent in GDP per capita, with 91 per cent of the contraction taking place in the fourth quarter (figure 1). As the military operation continued through May 2024, economic activity in Gaza fell to less than 20 per cent of the level in 2022. By early 2024, the decline in economic activity across the Occupied Palestinian Territory had exceeded the impact of previous confrontations in 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021, and was on course to surpass the impact of the aftermath of the second intifada that began in 2000 and continued for some years.

Table 1

Occupied Palestinian Territory: Selected quarterly indicators

Abbreviation: Q, quarter.

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) quarterly national accounts, consumer price index and labour survey.

Figure 1

(a) Gaza: Real gross domestic product

(Millions of constant 2015 dollars)

(b) Gaza: Real gross domestic product per capita

(Constant 2015 dollars)

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on PCBS quarterly national accounts.

5. Across the Occupied Palestinian Territory, value added in all sectors decreased in the fourth quarter of 2023 compared with in the same period in 2022 (figure 2), as follows: by 39 per cent in the construction sector (96 per cent in Gaza); by 38 per cent in the agricultural sector (93 per cent in Gaza); by 33 per cent in the services sector (77 per cent in Gaza); and by 28 per cent in the industrial sector (92 per cent in Gaza). Throughout 2023, Palestinian output declined in all sectors, as follows: by 12 per cent in construction; by 11 per cent in agriculture; by 8 per cent in industry; and by 6 per cent in services.

Figure 2

Quarterly value added by sector

(Millions of constant 2015 dollars)

(a) Occupied Palestinian Territory

(b) West Bank

(c) Gaza

Abbreviation: Q, quarter.

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on PCBS quarterly national accounts.

6. The military operation has decimated the agricultural sector in Gaza, damaging or destroying 80–96 per cent of agricultural assets by early 2024, including “irrigation infrastructure, livestock farms, orchards, agricultural holdings, machinery, storage facilities and research stations”.[5] The long-term consequences for nutrition, food security and poverty are evident.

7. The damage caused by the military operation has not been confined to Gaza, but has also affected the West Bank, where the occupying Power has tightened long-standing restrictions on the movement of Palestinian people and goods. According to the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS), entrances to most Palestinian towns and villages have been closed and new checkpoints have been deployed, increasing the total from 567 checkpoints in early October 2023 to 700 checkpoints by February 2024.[6]

8. Restrictions on movement hinder humanitarian aid delivery and undermine the economy by increasing transportation costs, investment risks and uncertainty, causing shortages of critical production inputs and consumer goods and impeding access by workers to job sites. By January 2024, 99 per cent of West Bank establishments participating in an International Labour Organization survey had been adversely impacted by measures implemented by the occupying Power since October 2023, with over 97 per cent experiencing a drop in sales, and small and medium-sized enterprises affected the most and having to implement permanent layoffs.[7]

9. East Jerusalem has also been affected. The confrontation has triggered a considerable downturn in commerce, tourism and transportation, resulting in the partial or complete cessation of operations, affecting 80 per cent of businesses in the Old City. According to MAS, the recovery of tourism from the pandemic-related shock has been reversed, with a decline in hotel room occupancy rates and the diversion of guests to hotels in Israel.[8]

10. Other cities in the West Bank have been affected by the loss of customers from Israel. Retail outlets, hotels and restaurants have been particularly impacted. For example, Jenin had over 4,800 economic establishments providing education, services, agriculture and handicrafts, and its proximity to the border with Israel and relatively lower prices had attracted cross-border shoppers from Israel, who accounted for a significant percentage of aggregate demand; and, according to MAS, the post-October 2023 crisis eliminated sales to these shoppers.[9]

11. The gap between actual values and pre-conflict projections of key indicators for 2023 serves to summarize the significant level of the damage inflicted: exports grew by 2.9 per cent versus the projected 5 per cent; imports contracted by 2.6 per cent versus projected growth by 5 per cent; the services sector contracted by 5.6 per cent versus projected growth by 3.7 per cent; the industrial sector contracted by 7.5 per cent versus projected growth by 3.2 per cent; and the agricultural sector contracted by 11.3 per cent versus projected contraction by 1 per cent.[10] The impact of the military operation on the agricultural sector is of particular concern, given the historical role of the sector in providing income, jobs and food security and in serving as a shock absorber that provides employment for displaced workers during frequent crises. In recent years, the sector has accounted for about 6 per cent of Palestinian GDP and the agrifood value chain has accounted for 15 per cent of GDP.[11]

12. Disruption to productive activities, delivery delays and trade disruptions have resulted in shortages of essential imports, including food and production inputs, and fuelled inflationary pressures. In the aftermath of the October 2023 shock, consumer prices in Gaza rose by 33 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2023; food prices rose by 39 per cent and fuel and gas prices, by 143 per cent.[12] PCBS data show that in the Occupied Palestinian Territory in 2023, inflation reached 6 per cent (4.8 per cent in the West Bank; 9.7 per cent in Gaza). Household welfare has thus been undermined by higher prices, increasing unemployment and declining incomes, with implications for poverty and food insecurity.[13] The opposing price effects of the dual shock to supply and demand did not offset each other. The inflationary impact of the supply shock has dominated the demand shock. The resulting high inflation rate, despite a sharp decline in all aggregate demand components, underscores the severity of the supply shock.

13. The disruption to import chains, restrictions on the movement of goods and the loss of incomes of Palestinians employed in Israel and settlements combined to reduce imports by one third in the fourth quarter of 2023. Exports fell by the same percentage, yet the trade deficit narrowed significantly in the fourth quarter of 2023 because imports were thrice as large as exports in absolute terms. The trade deficit increased from 45 per cent of GDP in 2022 to 48 per cent in 2023 (table 2). In addition, bilateral asymmetrical trade dependence persisted, as Israel accounted for roughly two thirds of total Palestinian trade, while the Palestinian share of total Israeli trade stood at about 3 per cent.

Table 2

Economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Key indicators

B. Mass unemployment

14. The confrontation has had a significant negative impact on the labour markets in both Gaza and the West Bank. In Gaza, unemployment reached 79 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2023, compared with 46 per cent in the third quarter of 2023 (see table 1).

15. UNCTAD has emphasized the significant reliance of the West Bank on employment in Israel and settlements, driven by the lack of jobs in the domestic labour market.[14] In 2022, 22.5 per cent of employed Palestinians from the West Bank worked in Israel and settlements, earning $4 billion, equivalent to 25 per cent of Palestinian GDP and 18.5 per cent of gross national income.[15] UNCTAD noted that this labour market dependence left the economy overly exposed to a highly unstable political environment. Such dependence should be overcome by freeing domestic producers from the occupation-related barriers that hinder investment and job creation and not by a sudden termination of employment in Israel and settlements.

16. Prior to October 2023, 171,000 West Bank Palestinians worked in Israel and settlements and their incomes accounted for one third of overall demand. Since the start of the confrontation, 90 per cent of these workers have lost their jobs, and additional restrictions and closures have prevented another 67,000 workers from accessing their workplaces outside their governates of residence.[16] In the fourth quarter of 2023, unemployment in the West Bank rose to 32 per cent, up from 12.9 per cent in the third quarter of 2023.[17] Over 200,000 jobs have been lost, most of them in Israel and settlements.

17. By end-January 2024, Gaza had lost two thirds of pre-October 2023 jobs (201,000 jobs). In the West Bank, less than 6 per cent of workers previously employed in Israel and settlements returned to work. In addition, 25 per cent of employment in the domestic private sector was lost, estimated at 144,000 jobs, for a total of 306,000 lost jobs in the West Bank, or one third of total employment. The International Labour Organization estimated the overall Occupied Palestinian Territory unemployment rate in the first quarter of 2024 at 57 per cent.[18]

18. In recent years, incomes earned by Palestinian workers in Israel and settlements played a key role in sustaining consumption-driven GDP growth. MAS estimates that a demand shock of one year’s suspension of employment in Israel and settlements could reduce GDP by 29 per cent.[19]

19. On the earnings side, the Palestinian Government has been paying employees partial salaries since November 2021; by January 2024, public employees had received 60 per cent of wages. By February 2024, the Palestinian Government owed employees arrears equivalent to 4.3 months of salary, with $48.4 million owed to employees in Gaza and $102.7 million owed to employees in the West Bank. In addition, 40 per cent of private sector workers in the West Bank experienced a wage reduction of about 20 per cent.[20] The job losses translate into labour income loss, estimated at $21.7 million per day. Adding the reduction in salaries of public and private sector employees raises the sum to $25.5 million per day.[21]

C. Multidimensional poverty

20. Since October 2023, all monetary and non-monetary welfare indicators have worsened, as multidimensional poverty has affected the entire population of Gaza. By early 2024, three out of four of the 2.3 million people in Gaza had been internally displaced, lacking proper shelter, facing starvation and experiencing shortages of water, fuel, electricity and a lack of access to education, health care and sanitation.[22]

21. In recent years, poverty has been widespread and increasing. By 2022, 80 per cent of the population of Gaza depended on international assistance, and aid was the primary source of income for more than half of households. One third of the Palestinian people (1.84 million people) were food insecure or severely food insecure, and 31.1 per cent were poor.[23]

22. Trends in poverty and inequality are closely linked to employment, income, expenditure and transfers. The poverty level is sensitive to small changes in expenditure in the West Bank and to changes in social assistance in Gaza.[24] Recent income loss and restrictions on the entry of humanitarian relief aggravate poverty across the Occupied Palestinian Territory and increase the threat of famine and starvation. The United Nations Development Programme stated that if the confrontation continued to mid-2024, the poverty rate could surge to 60.7 per cent and bring a large part of the middle class below the poverty line.[25] In Gaza, households have resorted to extreme strategies to cope with increasing poverty, including reducing meals, decreasing the food share of adults to feed children, bartering clothes and other items for food and gathering wild foods.[26] In the West Bank, households have dealt with the income shock through unsustainable measures such as borrowing, selling gold and other assets and vending on saturated streets in conditions of low demand and high cost. By May 2024, 88 per cent of school buildings in Gaza had sustained some level of damage.[27] The capacity of the health-care system to deliver adequate care has also been eroded due to 17 years of restrictions with regard to medical supplies. The latest military operation has further devasted medical facilities in Gaza, resulting in shortages of supplies, electricity and fuel.

23. In Gaza, by end-June 2024, over 37,396 Palestinians had reportedly been killed; 85,523, injured; and 1.7 million, displaced, in addition to 508 Palestinians killed in the West Bank.[28] The destruction, hunger and lasting trauma will have long-term implications for human capital formation, as human development in Gaza has already been set back by several decades.

24. The capacity of the Palestinian Government to provide basic services and social protection has been weakened by the lack of resources. The national cash transfer programme supported the most vulnerable groups, who received four quarterly cash payments that covered 15–30 per cent of minimum household needs. However, since 2017, coverage and payments fluctuated with the fiscal situation. By 2023, the programme had delivered less than 40 per cent of the coverage planned.[29] However, Government spending on health care has been significant, accounting for 13.2 per cent of the budget by 2022.[30]

D. Settlements and demolition in the West Bank

25. The United Nations Security Council, in its resolution 2334 (2016), reaffirmed that the establishment of settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, had no legal validity and constituted a flagrant violation under international law, and condemned all measures aimed at altering the demographic composition of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem. However, settlements have continued to expand and the recent transfer of administrative powers from military authorities to civilian officials in Israel could facilitate the annexation of settlements.[31]

26. Prior to the signing of the Oslo Accords, in 1993, there were about 250,000 settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. A subsequent hiatus on settlement expansion did not endure, and settlements and settler numbers continued to increase. By end-2023, the settler population had reached 700,000, with two thirds residing in Area C and the rest in East Jerusalem.[32] Settlement expansion is facilitated by economic incentives and infrastructure development, including the construction of bypass roads connecting settlements with each other and Israel, bypassing Palestinian cities. According to Peace Now, in recent years, there has been an increase in road construction, with 13 bypass roads developed in 2020 alone.[33]

27. Settlements hinder a two-State solution, alter the reality on the ground, fragment Palestinian geography and markets and impede economic development through the confiscation of land, water and natural resources.

28. In Area C, which constitutes about 60 per cent of the West Bank and holds valuable resources, it is nearly impossible for Palestinians to obtain permits from authorities in Israel to build structures for residential, industrial, agricultural or infrastructure-related purposes. According to B’Tselem, until 2016, the rejection rate for building applications was 98 per cent and, in recent years, the rate has risen to 99 per cent.[34] However, the number of applications does not fully reflect Palestinian needs, as many potential applicants do not apply; if actual needs are considered, the rejection rate might exceed 99 per cent. Inability to build or invest in Area C constrains Palestinian development because Areas A and B have limited room for development and urban expansion, while resource-rich Area C is sparsely populated, with 200,000–300,000 Palestinians.

29. If Palestinians build without a permit, the structures are demolished by the occupying Power. According to the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, in 2009–late-April 2024, the occupying Power demolished 10,686 structures, leading to the displacement of 16,110 Palestinians. The affected structures included residential buildings, livelihood-related facilities, service-related facilities and infrastructure components such as water pipes, roads and network facilities.[35]

30. In 2023, the demolition of Palestinian structures in the West Bank reached the highest level since registration began in 2009, with 1,177 structures demolished, of which 106 had been donor funded, leading to the displacement of 2,296 Palestinians and affecting 44,000 people.[36] Notably, demolitions disproportionately impact women-headed households, as displacement entails not only the loss of shelter but also privacy and safety.

31. Settler violence has escalated significantly since 7 October 2023. Incidents of violence, including intimidation, physical assaults, crop destruction and vandalism, increased from an average of three incidents per day in the first nine months of 2023 to eight incidents per day in 7–31 October.[37] The combination of settler violence, restrictions on access to land and water and demolitions creates an environment of forced relocation that magnifies the impact of the growth of settler populations on the demographic structure of Area C and East Jerusalem.[38]

II. The cost of fiscal and monetary dependency

A. Unilateral deductions and withholding of revenue aggravating the fiscal crisis

32. Over the last decade, the Palestinian Government has implemented far-reaching fiscal reforms towards sustainability. By 2023, the Palestinian Government had reduced the total budget deficit to 3 per cent of GDP, down from 26.1 per cent in 2008, a significant achievement in an environment of occupation and recurring political, economic and humanitarian crises. However, Palestinian fiscal policy space has been progressively shrinking. Below-potential GDP growth, deductions by Israel, leakage of Palestinian fiscal resources to the occupying Power and a steep decline in donor aid have collectively contributed to a severe fiscal crisis that involves substantial financing gaps, mounting public debt and arrears owed to private sector entities, public sector employees and the pension fund. The changes in key fiscal indicators show the achievements in reducing the deficit, the build-up of public debt and the decline in donor aid (figure 3).

Figure 3

Selected fiscal indicators

(Percentage of gross domestic product)

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on data from the Palestinian Ministry of Finance and Planning.

33. A quarter of a century since its expected expiry in 1999, the Paris Protocol continues to define the revenue clearance mechanism, whereby Israel collects taxes on Palestinian imports from or via Israel and makes monthly transfers to the Palestinian Government. This arrangement leaves over two thirds of Palestinian fiscal revenue under the control of the occupying Power, which can (and often does) suspend transfers and apply deductions. Since 2019, the Government of Israel has been deducting from clearance revenue amounts equivalent to the payments made by the Palestinian Government to families of Palestinian prisoners in Israel and Palestinians killed in attacks or alleged attacks against Israelis. According to the Palestinian Ministry of Finance and Planning, in 2019–April 2024, these deductions amounted to $863 million, equivalent to 5 per cent of Palestinian GDP in 2023. Since October 2023, the occupying Power has withheld additional amounts, approximately $75 million per month, equivalent to the payments made by the Palestinian Government to civil servants in Gaza. According to data from the Palestinian Ministry of Finance and Planning, in October 2023–May 2024, $483 million was withheld under this item. This raises monthly withholding and deductions to about half the clearance revenues. Deductions and withheld amounts have increased since October 2023 (figure 4). In 2019–April 2024, cumulative deductions and withheld amounts surpassed $1.4 billion, equivalent to 8.1 per cent of GDP in 2023. The loss of revenues undermined the capacity of the Government to provide essential services and pay employees, pensioners and creditors.

Figure 4

Israel deductions and withheld amounts

(Millions of dollars)

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on data from the Palestinian Ministry of Finance and Planning.

34. The Paris Protocol stipulates that the Government of Israel is to collect tax revenues in Area C and remit them to the Palestinian Government, but this has not yet taken place. UNCTAD estimates the average GDP produced by the occupying Power, using Palestinian land and natural resources, in settlements in East Jerusalem and Area C, at $41 billion per year.[39] The Israeli tax revenue, approximately 33 per cent, indicates that the occupying Power collects several billion dollars in revenue from economic activities in settlements in East Jerusalem and Area C.

35. Fiscal policy recommendations have overemphasized revenue enhancement and expenditure rationalization, while the dominant causes of the fiscal crisis are occupation-related constraints on investment, labour and trade, as well as the leakage of Palestinian fiscal resources and deductions by the occupying Power. Fiscal sustainability requires ending occupation and granting the Palestinian Government sovereign control over its borders, trade and independent revenue collection.

B. Procyclical austerity compounding the economic crisis

36. In 2023, total revenues (excluding grants) contracted by 10 per cent, compared with pre-conflict projections.[40] Declining donor aid added to the severity of fiscal pressure.

37. The Palestinian Government lacks essential economic policy tools, compared with fully sovereign States; there is no central bank, no national currency and no access to international financial markets. Under severe resource constraints, the Palestinian Government has responded to the impacts of the military operation subsequent to the events of 7 October 2023 with an effectively procyclical, involuntary austerity, which has magnified the negative impact of the supply shock on GDP growth. The Palestinian Government has resorted to unsustainable measures, including accumulating debt, delaying payments to private suppliers, reducing social transfers to the poor and providing partial salaries to employees while curtailing essential public services such as health care and education. Public employees have been paid partial salaries since November 2021. By end‑2023, Government employees had been paid 50 per cent of October salaries and 64 per cent of November salaries; by February 2024, employees had been paid 60 per cent of December salaries.[41]

38. Public debt increased from $3.54 billion in 2022 to $3.78 billion in 2023. The Palestinian Government also accumulated an additional $1.13 billion in new arrears to its employees and the private sector. The financing gap in 2023 after aid reached $682 million, or 3.9 percent of GDP, and the situation is expected to further decline in 2024, with a potential financing gap of up to $1.2 billion.[42]

39. The downward trend in donor aid continued in 2023, with total aid at $358 million, equivalent to 2 per cent of GDP, with $206 million for budget support. Reversing this trend is crucial for the Palestinian Government to be able to maintain essential public services, pay salaries and pensions, clear arrears and sustain aggregate demand. The fiscal impact on aggregate demand constricts economic growth and thereby reduces fiscal revenue, posing the risk of a downward spiral, whereby the fiscal constraint weakens economic performance and weak GDP growth diminishes public revenues.

C. Fiscal pressures and the banking system

40. In recent years, the stability of the banking system has faced several challenges, including the disruption of correspondent banking relations with Israel, the overall economic decline that lowers asset quality and engenders defaults and the exposure of banks to the Government and public employees.

41. According to MAS, the latest military operation has led to the destruction of physical bank assets, including buildings and cash machines. Gaza accounted for 10.6 per cent of total private credit facilities and 11.6 per cent of customer deposits within the banking system, as well as 8 per cent of the total assets, valued at $22.8 billion.[43]

42. The military operation has impacted banks in the West Bank through several channels, including the heightened direct and indirect exposure to the Government and increased incidents of default and returned checks associated with the loss of jobs and incomes.

43. Amid concerns about the high level of exposure of the banking system to the Palestinian Government and its employees, by mid-2023, the Government managed to lower borrowing to $2.3 billion, close to the limit set by the Palestinian Monetary Authority. As a result, exposure of the banking system fell to 37 per cent of total banking credit, or $4.2 billion.[44] However, the fiscal ramifications of the military operation prompted the Government to borrow $400 million from banks and thereby heightened the potentially destabilizing exposure of the banking system. In addition, by end-2023, arrears to private suppliers and the pension fund had risen from 33.6 per cent to 40.9 per cent of GDP.[45]

44. The Palestinian Monetary Authority monitors indicators of financial stability and has strengthened prudential regulations with regard to capital requirements and to safeguard against excessive credit growth and sectoral concentration.[46] Following the start of the recent confrontation, the Authority implemented emergency measures to maintain banking stability and guard against direct and indirect spillovers from Gaza. The Authority extended low interest rate loans to small and medium-sized enterprises to assist them, and initiated support for Palestinians who had lost jobs in Israel and settlements in the form of zero interest loans. Given modest and cautious lending, stress tests suggest that the banking sector remained resilient by mid-2024.[47]

45. Despite the lack of a sovereign national currency and given a narrow fiscal space, the Palestinian Government has insulated the banking sector from the fiscal crisis. However, if the crisis persists, it may hinder the ability of the Government to service debt to banks and private sector suppliers. In addition, the payment of partial salaries to public employees limits their ability to service debt to banks and obtain fresh credit.

46. The Palestinian economy relies on the new shekel as the dominant currency in circulation, with the American dollar and Jordanian dinar used for secondary purposes, particularly in real estate transactions. In recent years, the accumulation of excess physical cash in new shekels has impacted the profitability of Palestinian banks.[48] The arrangement whereby Palestinian banks shipped such excess cash to correspondent banks in Israel came to an end in 2009 when Israel terminated cash services following the designation of Gaza by the Government of Israel as a “hostile entity”, citing concerns among banks in Israel related to money laundering and the financing of terrorism.[49] The Bank of Israel began to service cash shipments from banks operating in the West Bank, but set a monthly limit on the amount accepted. Since 2017, temporary measures allowing banks in Israel to deal with Palestinian banks have been extended several times, but uncertainty remains, and the accumulation of excess cash has continued over the limit of 6 per cent of short-term new shekel deposits set by the Palestinian Monetary Authority. Wages and salaries paid in cash to authorized and unauthorized Palestinian workers in Israel and settlements account for most cash inflows in new shekels, followed by informal trade between Israel and the West Bank, fuelled by shoppers from Israel.[50]

47. The accumulation of excess cash undermines the profitability of banks through several channels, including foregone opportunities and inflated costs. Excess cash undermines the capacity of banks to optimize operations and manage cash flows; banks are forced to eschew business opportunities in sectors and activities dominated by cash transactions such as retail establishments, gas stations and restaurants. In addition, the cost of securing and insuring excess cash reached $12 million in 2021. The direct and opportunity costs of foregone interest earnings and profits reduces the profitability of Palestinian banks by about 20 per cent, and the cost of excess cash in new shekels extends beyond banks. The accumulation of billions of new shekels enlarges the informal sector, estimated at over 50 per cent of GDP.[51]

48. A sizable informal sector is associated with many problems, including narrowing the tax base, discouraging productivity growth, encouraging small-size inefficiency and lowering GDP growth. In addition, workers in the informal sector often lack protection, as they tend to be employed without contracts and at low pay levels, often below minimum wage. Dollarization, or recourse to any other currency, may not be a realistic solution to the problems arising from currency dependency, including due to the significant dependence of the Palestinian economy on that of Israel, the main trading partner. The Palestinian Government receives clearance revenue (about two third of its revenue) from the Government of Israel in new shekels, used to pay salaries and pensions and settle transactions with Israel. Short of currency independence, a possible solution is to ensure that banks in Israel accept the return of new shekels issued by the Bank of Israel.

D. The enduring crisis threatens the achievements of the Palestinian National Authority

49. Since its establishment in 1994, the Palestinian National Authority has embarked on a state-building project with international support. The success of the Palestinian National Authority in building essential governance institutions has been widely recognized, as early as in 2011, including by the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations and the World Bank.[52]

50. The Government achieved success in education and health, with Palestinians generally outperforming regional comparators across key indicators. However, in recent years, gains have stagnated or reversed due to continuing loss of land and natural resources, leakage of fiscal resources to the occupying Power and a decline in foreign support.

51. In 1994–2023, the international community extended at least $44 billion in official development assistance to the Occupied Palestinian Territory; of the total, grants and loans for development projects accounted for 43 per cent, budget support accounted for

35 per cent and humanitarian assistance accounted for 21 per cent.[53] The composition of international support has varied over time. Until 1999, most assistance funded development and infrastructure projects. However, following the second intifada, economic decline and security crises shifted the focus to humanitarian relief, at the cost of development. The recent military operation will further divert support toward relief and the replacement of damaged infrastructure. Budget support had begun to decline by 2013. By 2021, the share of budget support in total assistance was at roughly 9 per cent, the lowest level since 2000; humanitarian assistance accounted for 36 per cent; and grants and lending for development projects, the private sector and the security sector accounted for the remainder.[54]

52. The significant achievements of the Palestinian Government notwithstanding, occupation has deepened, settlements have continued to expand in the West Bank, Gaza has been under restrictions and closures for over a decade and a half and permanent status issues remain unresolved. The recent military operation increases the negative effects.

53. A quarter of a century since its expected expiry in 1999, the Paris Protocol remains the general framework that shapes Palestinian macroeconomic, fiscal and trade policies. Implementation of the protocol has been weak, selective and subject to conflicting interpretations by unequal sides. UNCTAD has previously stated the need to update the Paris Protocol, and this has also been noted by the Office of the Quartet in 2022 and the United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process in 2022 and 2023.[55]

III. UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people

A. Framework and objectives

54. For over three and a half decades, UNCTAD has been supporting the Palestinian people through policy-oriented research, the implementation of capacity-building and technical cooperation projects, the provision of advisory services and the promotion of international consensus on the needs of the Palestinian people and their economy.

55. The UNCTAD programme of assistance to the Palestinian people responds to paragraph 127 (bb) of the Bridgetown Covenant, which requests UNCTAD to “continue to assess the economic development prospects of the Occupied Palestinian Territory and examine economic costs of the occupation and obstacles to trade and development… with a view to alleviating the adverse economic and social conditions imposed on the Palestinian people”. Furthermore, the United Nations General Assembly, in eight resolutions (69/20, 70/12, 71/20, 72/13, 73/18, 74/10, 75/20 and 77/22), requested UNCTAD to continue to report to the General Assembly on economic development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the economic costs of the Israeli occupation for the Palestinian people.

56. The UNCTAD programme, which aims to build and strengthen the institutional capacities of the Palestinian public and private sectors, addresses the constraints to and emerging needs of the Palestinian economy through the following four clusters:

(a) Trade and macroeconomic policies and development strategies;

(b) Trade facilitation and logistics;

(c) Finance and development;

(d) Enterprise, investment and competition policy.

B. Operational activities under way

57. In response to the above-mentioned resolutions, in 2023, UNCTAD submitted a report to the General Assembly titled “Economic costs of the Israeli occupation for the Palestinian people: The welfare cost of the fragmentation of the occupied West Bank”. The report focused on the economic cost of the Israeli occupation of Area C, which constitutes 60 per cent of the West Bank, and estimated the cost of the additional restrictions on economic activities in Area C in terms of household welfare.[56]

58. In October 2022, UNCTAD signed a grant agreement with MAS, under which UNCTAD and MAS updated the MAS macroeconometric model and organized training for Palestinian Government professionals and researchers on the structure and use of the UNCTAD integrated simulation framework. In May 2023, UNCTAD updated the macroeconometric model and, in collaboration with MAS, trained Palestinian researchers and officials from the Ministry of Finance and Planning, the Palestinian Monetary Authority and PCBS on using the updated model.

59. In November 2023, UNCTAD provided advisory services to MAS through a series of online meetings on assessing the economic impact of the Israeli military operation in Gaza.

60. In January 2024, UNCTAD issued “Preliminary assessment of the economic impact of the destruction in Gaza and prospects for economic recovery”.[57]

61. In 2024, UNCTAD has been preparing a study on the occupation, fragmentation and poverty in the West Bank. The study seeks to quantify the welfare cost of the fragmentation of the West Bank with reference to the relative share of the occupied Area C in Palestinian localities.

C. Coordination, resource mobilization and recommendations

62. In 2023, in line with its mandate, UNCTAD continued its support to the Palestinian people in coordination with the Palestinian Government, international organizations, donors, the United Nations country team and other stakeholders, including civil society, providing research and policy analysis, gathering evidence and proposing policy recommendations with a view to alleviating the adverse economic and social conditions imposed on the Palestinian people and pursuing the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. The programme continued its ongoing support for the Palestinian people despite adverse and increasingly difficult field conditions.

63. In 2020, UNCTAD received a grant from the Government of Saudi Arabia to sustain the professional capacity required at UNCTAD. The grant funded a project that provided systematic, evidence-based assessments of the economic cost of the occupation for the Palestinian people. The goal was to facilitate future negotiations towards achieving a just and lasting peace in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and the Middle East. The project was successfully concluded by the end of June 2023.

64. A shortage of extrabudgetary resources continues to limit the ability of UNCTAD to deliver on its mandates and meet the growing need for technical assistance by the Palestinian people and other stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector. Therefore, member States are invited to consider extending extrabudgetary resources to enable UNCTAD to fulfil the requests made in the Bridgetown Covenant and in United Nations resolutions.

* The designations employed, maps and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In accordance with the relevant resolutions and decisions of the General Assembly and Security Council, references to the Occupied Palestinian Territory or territories pertain to the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Use of the term “Palestine” refers to the Palestine Liberation Organization, which established the Palestinian National Authority. References to the “State of Palestine” are consistent with the vision expressed in Security Council resolution 1397 (2002) and General Assembly resolution 67/19 (2012).

** The document was submitted late to the conference services for processing without the explanation required under paragraph 8 of General Assembly resolution 53/208 B.

[1] World Bank, 2024a, Note on the impacts of the conflict in the Middle East on the Palestinian economy, available at https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/db985000fa4b7237616dbca501d674dc-0280012024/note-on-the-impacts-of-the-conflict-in-the-middle-east-on-the-palestinian-economy.

[2] TD/B/EX(74)/2 and UNCTAD, 2024, Preliminary assessment of the economic impact of the destruction in Gaza and prospects for economic recovery, January, available at https://unctad.org/publication/preliminary-assessment-economic-impact-destruction-gaza-and-prospects-economic-recovery.

[4] International Monetary Fund, 2023, Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, 8 September.

[6] MAS, 2024a, Policy brief: Methods to address West Bank cities’ economic losses since the start of the Gaza war, available at https://mas.ps/cached_uploads/download/2024/02/13/pb1-2024-eng-1707811228.pdf.

[7] International Labour Organization, 2024, Impact of the war in Gaza on the labour market and livelihoods in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, bulletin No. 3, available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/impact-war-gaza-labour-market-and-livelihoods-occupied-palestinian.

[8] MAS, 2024b, Palestine economic update, February, available at https://mas.ps/en/publications/9668.html.

[9] MAS, 2024a, and MAS, 2024b.

[13] PCBS and Palestine Monetary Authority, 2024, The performance of the Palestinian economy for 2023, and economic forecasts for 2024, available at https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/512/default.aspx?lang=en&ItemID=4672.

[16] See https://www.ilo.org/publications/impact-escalation-hostilities-gaza-labour-market-and-livelihoods-occupied.

[18] See https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/palestinian-unemployment-rate-set-soar-57-cent-during-first-quarter-2024.

[19] MAS, 2024c, Palestine economic update, April, available at https://mas.ps/en/publications/10212.html.

[20] International Labour Organization, 2024.

[22] See https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-26-june-2024 and https://www.ochaopt.org/content/humanitarian-situation-update-184-gaza-strip.

[23] See https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/wfp-palestine-country-brief-august-2023.

[24] World Bank, 2023a, Poverty and equity brief: West Bank and Gaza, April, available at https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_PSE.pdf.

[25] See https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-05/2400314e-keymessages-gaza-web.pdf.

[26] Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, 2024, Special brief, March, available at https://www.ipcinfo.org/

fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Gaza_Strip_Acute_Food_Insecurity_Feb_July2024_Special_Brief.pdf.

[27] See https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-26-june-2024.

[29] United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, 2023, Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, 15 September, available at https://unsco.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/unsco_ahlc_report_-_september_2023.pdf.

[30] World Bank, 2023b, Economic monitoring report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, September, available at https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099638209132320721/idu0e8b2e87e098b004a7a09dcb07634eb9548f4.

[32] Peace Now, 2023, 30 years after Oslo, available at https://peacenow.org.il/en/30-years-after-oslo-the-data-that-shows-how-the-settlements-proliferated-following-the-oslo-accords.

[34] See https://www.btselem.org/sites/default/files/publications/202309_pogroms_are_working_

transfer_already_happening_eng.pdf.

[35] See https://www.ochaopt.org/data/demolition.

[37] See https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/Palestine-March2024.pdf and https://www.btselem.org/

sites/default/files/publications/202309_pogroms_are_working_transfer_already_happening_eng.pdf.

[39] UNCTAD, 2022, The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: The Cost of Restrictions in Area C Viewed from Above (United Nations publication, Geneva).

[42] World Bank, 2024b, Economic monitoring report, May, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/05/23/world-bank-issues-new-update-on-the-palestinian-economy.

[46] International Monetary Fund, 2023.

[47] World Bank, 2024a, and MAS, 2024b.

[48] International Monetary Fund, 2023.

[49] International Monetary Fund, 2022, West Bank and Gaza: Selected issues, 13 September, available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/09/15/West-Bank-and-Gaza-Selected-Issues-523402.

[52] See https://www.imf.org/-/media/external/country/WBG/RR/2011/041311.ashx and https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/423451468176985450/Building-the-Palestinian-state-sustaining-growth-institutions-and-service-delivery-economic-monitoring-report-to-the-Ad-Hoc-Liaison-Committee

[53] United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, 2023.

[55] See https://www.quartetoffice.org/files/Office%20of%20the%20Quartet%20Report%20to%

20the%20AHLC%20-%20September%202022.pdf, https://unsco.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/unsco_report_to_the_ahlc_-_22_september_2022.pdf and https://unsco.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/unsco_ahlc_report_-_september_2023.pdf.

Download Document Files: https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/g2412912.pdf

Document Type: Report

Document Sources: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

Subject: Armed conflict, Development, Economic issues, Gaza Strip, Human rights and international humanitarian law, Jerusalem, Poverty, West Bank

Publication Date: 23/07/2024

URL source: https://undocs.org/TD/B/71/3