World Economic Situation And Prospects: May 2018 Briefing, No. 114

- Rising trade tensions pose a risk to the global trade outlook

- Africa marks an historic step towards the creation of a regional trade bloc

English: PDF (172 kb), EPUB (339 kb)

Global issues

Escalation of trade policy disputes poses risk to recovery in global trade

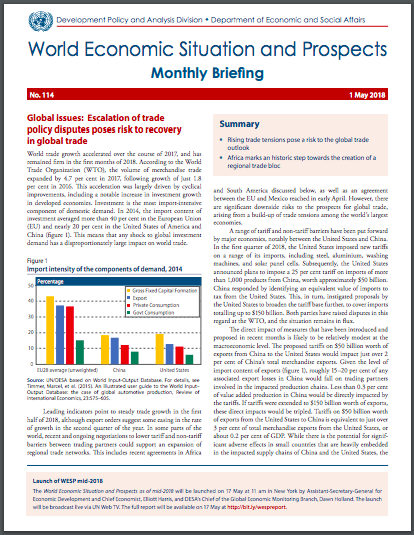

World trade growth accelerated over the course of 2017, and has remained firm in the first months of 2018. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the volume of merchandise trade expanded by 4.7 per cent in 2017, following growth of just 1.8 per cent in 2016. This acceleration was largely driven by cyclical improvements, including a notable increase in investment growth in developed economies. Investment is the most import-intensive component of domestic demand. In 2014, the import content of investment averaged more than 40 per cent in the European Union (EU) and nearly 20 per cent in the United States of America and China (figure 1). This means that any shock to global investment demand has a disproportionately large impact on world trade.

Leading indicators point to steady trade growth in the first half of 2018, although export orders suggest some easing in the rate of growth in the second quarter of the year. In some parts of the world, recent and ongoing negotiations to lower tariff and non-tariff barriers between trading partners could support an expansion of regional trade networks. This includes recent agreements in Africa and South America discussed below, as well as an agreement between the EU and Mexico reached in early April. However, there are significant downside risks to the prospects for global trade, arising from a build-up of trade tensions among the world’s largest economies.

A range of tariff and non-tariff barriers have been put forward by major economies, notably between the United States and China. In the first quarter of 2018, the United States imposed new tariffs on a range of its imports, including steel, aluminium, washing machines, and solar panel cells. Subsequently, the United States announced plans to impose a 25 per cent tariff on imports of more than 1,000 products from China, worth approximately $50 billion. China responded by identifying an equivalent value of imports to tax from the United States. This, in turn, instigated proposals by the United States to broaden the tariff base further, to cover imports totalling up to $150 billion. Both parties have raised disputes in this regard at the WTO, and the situation remains in flux.

The direct impact of measures that have been introduced and proposed in recent months is likely to be relatively modest at the macroeconomic level. The proposed tariffs on $50 billion worth of exports from China to the United States would impact just over 2 per cent of China’s total merchandise exports. Given the level of import content of exports (figure 1), roughly 15–20 per cent of any associated export losses in China would fall on trading partners involved in the impacted production chains. Less than 0.3 per cent of value added production in China would be directly impacted by the tariffs. If tariffs were extended to $150 billion worth of exports, these direct impacts would be tripled. Tariffs on $50 billion worth of exports from the United States to China is equivalent to just over 3 per cent of total merchandise exports from the United States, or about 0.2 per cent of GDP. While there is the potential for significant adverse effects in small countries that are heavily embedded in the impacted supply chains of China and the United States, the global impact of tariffs of this magnitude is likely to be relatively small.

The direct impact of measures that have been introduced and proposed in recent months is likely to be relatively modest at the macroeconomic level. The proposed tariffs on $50 billion worth of exports from China to the United States would impact just over 2 per cent of China’s total merchandise exports. Given the level of import content of exports (figure 1), roughly 15–20 per cent of any associated export losses in China would fall on trading partners involved in the impacted production chains. Less than 0.3 per cent of value added production in China would be directly impacted by the tariffs. If tariffs were extended to $150 billion worth of exports, these direct impacts would be tripled. Tariffs on $50 billion worth of exports from the United States to China is equivalent to just over 3 per cent of total merchandise exports from the United States, or about 0.2 per cent of GDP. While there is the potential for significant adverse effects in small countries that are heavily embedded in the impacted supply chains of China and the United States, the global impact of tariffs of this magnitude is likely to be relatively small.

Assessing the macroeconomic impact of a tariff requires an understanding of both the direct impact on the targeted sector and the indirect impact elsewhere in the economy. For instance, a tariff on steel may support production within the steelmaking industry, as domestic firms are better able to compete with lower-cost producers abroad. However, in steel consuming industries, the tariff may raise production costs and squeeze firm profits, potentially leading to job losses or lower wages. In addition, higher steel prices may feed to the broader macroeconomy through higher consumer prices, dampening overall household demand. Uncertainty and a loss of business confidence, in the face of a rapidly-changing trade policy landscape, can lead to a sharp drop of investment in the short-term, as firms postpone investment decisions until the regulatory environment settles. In the medium-term, prolonged weak trade and investment activity will adversely impact growth prospects for the global economy, particularly given the deep linkages between trade, investment and productivity growth.

The net impact of any tariff on the macroeconomy will as also depend on the spillovers and reactions by the rest of the world. Trade restrictive measures can disrupt the complex global and regional production networks that have evolved over the past decades under various trade arrangements, with potentially large adverse effects on many smaller developing countries integrated into those supply chains. Given the high import content of investment, a shock to global business confidence could spread rapidly through these networks. The global automotive and computing sectors, as well as the construction industry, are deeply embedded within global value chains, and could face severe disruptions.

The baseline forecast projections of the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018 and its forthcoming Update as of mid-2018 are based on an assumption that trade tensions do not escalate significantly from current levels and that global spillovers remain contained; world gross product growth is forecast to reach at least 3 per cent in 2018-2019. Under an alternative scenario, where trade tensions and barriers were instead to spiral over the course of 2018, with extensive disruptions to global value chains, this could instead trigger a sharp drop in global investment and trade.

Figure 2 illustrates the potential global impact of a scenario where escalating global trade barriers induce a postponement of 6 per cent of investment in developed economies and in China until after 2019, based on model simulations using UN/DESA’s World Economic Forecasting Model (WEFM). For context, the impacts are compared to changes in the same variables in 2009, at the height of the global financial crisis. The scenario suggests that a steep escalation of global trade barriers could reduce world gross product growth by 1.4 percentage points in 2019, and slow world trade growth by more than 6 percentage points. Trade losses of this magnitude are roughly half that experienced in 2009. If the recent trend towards increasing trade disputes were to escalate into a spiral of retaliation, the repercussions for the world economy, including many developing countries, could prove severe.

Figure 2 illustrates the potential global impact of a scenario where escalating global trade barriers induce a postponement of 6 per cent of investment in developed economies and in China until after 2019, based on model simulations using UN/DESA’s World Economic Forecasting Model (WEFM). For context, the impacts are compared to changes in the same variables in 2009, at the height of the global financial crisis. The scenario suggests that a steep escalation of global trade barriers could reduce world gross product growth by 1.4 percentage points in 2019, and slow world trade growth by more than 6 percentage points. Trade losses of this magnitude are roughly half that experienced in 2009. If the recent trend towards increasing trade disputes were to escalate into a spiral of retaliation, the repercussions for the world economy, including many developing countries, could prove severe.

Developed economies

Japan: Uncertain prospects with Japan’s largest trading partners

Steel tariffs introduced by the United States are expected to have only a marginal direct impact on the Japanese steel industry. In 2017, the United States accounted for just 8 per cent of Japan’s exports of steel and aluminium products. In the short term, the cost of tariffs will largely be transferred to customers, as the specialized quality specifications of Japanese products cannot be substituted readily by other countries. Nevertheless, the escalating trade dispute between China and the United States—two of Japan’s largest trading partners—is casting a shadow on the prospects of the Japanese economy. China accounted for 22 per cent of Japan’s trade in 2017, up from 10 per cent in 2000. In the same period, the United States’ share of Japan’s trade has decreased from 25 per cent to 15 per cent. While Japan continues to run persistent trade deficits with China, trade with the United States makes the largest contribution to Japan’s trade surplus.

Europe: Rising trade tensions with the United States and China

With the announcement by the United States of its intention to levy tariffs on various goods, trade tensions between the EU and the United States have increased. The EU and the United States are each other’s largest export destinations, with total trade in goods amounting to $722 billion in 2017 and the balance standing at a deficit for the United States of $153 billion. In reaction to the United States announcement, the EU outlined a set of measures it would take on its part, including opening a case at the WTO, protective measures specifically aimed at preventing a surge in steel imports and tariffs on various types of products from the United States. The proposed range of goods has so far been relatively small, compared to the overall trade volume, but given that exports to the EU account for almost 19 per cent of total exports from United States, there is a risk that trade tensions may escalate further.

At the same time, trade tensions have also been increasing between the EU and China. China represents the EU’s largest import origin, with about 20 per cent of all EU imports, and its second largest export destination. Issues that have moved to the fore include the conditions for market access and for company ownership. Negotiators will face the need to deal with the concept of reciprocity regarding these issues, which creates uncertainty regarding future trade developments.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Geopolitical tensions may impact trade prospects

In the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) area, the launch of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in 2015 laid the foundations for free trade among its members. The 2015–2016 recession in the Russian economy temporarily suppressed the expansion in internal EAEU trade, although the Russian Government’s restrictions on food imports from most OECD countries has facilitated food exports of some CIS countries; while the sharp depreciation of the Russian rouble and several other EAEU currencies in 2015 led to a strong contraction in external imports to the EAEU (total Russian import volume contracted by 25.9 per cent in 2015). The exit of the Russian economy from recession in 2017 has spurred EAEU internal trade, although a recent weakening of the rouble may curb Russian import demand.

The escalation of geopolitical tensions between the Russian Federation and several countries in early 2018 has led to the introduction of additional sanctions restricting international activities of several large Russian companies. Possible counter-measures currently under discussion in the Russian Federation may further constrain external trade. Several sectors of the Russian economy that are integrated into global production chains and require access capital markets, such as aluminium production, are likely to be heavily affected in the near term. Restricted access to the modern oil-drilling technology may have a longer-term impact on the hydrocarbon sector, which accounts for the majority of Russian exports.

Outside of the EAEU, Ukraine’s foreign trade has gradually reoriented towards the EU, following the military conflict and the collapse of industry in eastern Ukraine, loss of the Russian market, and the conclusion of the Association Agreement with the EU in 2014. Similar agreements were signed by Georgia (not a CIS member) and the Republic of Moldova in 2016; the market of the Russian Federation remains, nevertheless, important for both countries. Azerbaijan’s exports remained relatively stable in volume terms in 2015–2017, but their dollar value sharply declined in 2015, causing a noticeable fall in imports, which has yet to fully recover. Tajikistan’s external trade also suffered setbacks in 2015–2016, with imports contracting as the value of inward remittances dwindled and currency plunged; exports performed better and surged in 2017 thanks to stronger economic activity in Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation and higher aluminium prices.

Developing economies

Africa: Historic free trade agreement signed

On 21 March 2018, 44 member States of the African Union signed the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement. The free trade agreement commits signatory countries to removing tariffs on 90 per cent of goods, with 10 per cent of designated items to be phased in later. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the AfCFTA is estimated to boost intra-African trade by 52.3 per cent through the elimination of import duties.

A free trade area is essential to establish a sizeable regional cluster of markets, which enables African economies to localize more value-added processes in global value chains. Currently, goods are mostly exported at an upstream commodity stage, while imports are mostly final goods. As such, African economies miss out most of the value-added process. The small size of domestic markets hinders many African economies from expanding into the production of intermediate goods, and reaping the benefits of participating in a larger part of the production stream.

It is well known that East Asian economies have successfully established regional clusters of markets, enabling them to take advantage of intraregional trade, which has in turn contributed to the region’s rapid industrial development. While a gradual change in economic structure is ongoing in Africa, intraregional trade accounted for just 16 per cent of Africa trade in 2017, compared to 57.5 per cent in East and South Asia. East and South Asia have also accounted for an increasing share of interregional trade with Africa, rising from 15 per cent in 2000 to 32 per cent in 2017. This has been offset by a declining share of trade with Europe. The change in geographical intensity in trade reflects the changing dynamics of global supply chains, which could be a window of opportunity for African countries to diversify their economies.

East Asia: Proposed tariffs a risk to the region’s E&E industry

The solid performance of East Asia’s export growth that was observed in 2017 extended into the first few months of 2018. While recent figures may be distorted by the Lunar New Year holiday, leading indicators such as Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Indices and export orders suggest that export growth is likely to remain positive, but the expansion will proceed at a more moderate pace.

The region’s buoyant export growth over the past year has been driven mainly by strong shipments of electrical and electronic (E&E) products. In 2017, E&E exports contributed more than half of total export growth in China, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan Province of China. In Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore, E&E accounted for between 30 to 40 per cent of the rebound in exports. Meanwhile, the upturn in global electronics demand benefitted Indonesia and Philippines to a much lesser degree, with E&E exports making up less than 5 per cent of export growth in these economies.

A sharply more restrictive international trade environment poses a key downside risk to East Asia’s growth prospects, given the region’s high trade openness and extensive global production networks. While the direct impact of the proposed tariffs by the United States and China are expected to be limited, the indirect effects can be substantial given that they may disrupt supply chains in the region, particularly in the E&E industry. Furthermore, the tariffs are likely to lead to higher production costs and lower firm profits, thus weighing on investment in the region.

South Asia: Export growth is picking-up, but boosting medium-term competitiveness a major challenge for the region

The performance of exports in South Asia is gradually picking-up in several economies, underpinned by improving global economic conditions and the revival in international trade observed recently. In Bangladesh, exports have shown a more solid performance since the end of 2017, especially in the garment sector. In January, exports grew at its fastest pace since mid-2017, and export earnings in the first seven months of the FY2017/18 were up by 7.0 per cent, year-on-year. The outlook for garment exports remains favourable, as Bangladesh continues to gain relevance in the ongoing shift in this industry away from China. In addition, the outlook for demand from major destinations, such as the United States and the EU, remains positive. In Pakistan, export growth is gradually recovering, after tumbling for several years. Between July 2017 and February 2018, exports earnings increased by about 11 per cent year-on-year. However, the recent surge in imports due to strong domestic demand has also raised concerns on the sustainability of the current account deficit. In India, the performance of exports has also improved since the end of 2017, as the short-term effects from the demonetization policy and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) reform dissipated. In the FY2017/18, the value of exports increased by more than 9.0 per cent, the highest pace since 2012.

While domestic demand continues to be the main driver of growth across the region and the cyclical upturn in the export performance is encouraging, the region needs to redouble its policy efforts towards strengthening its international competitiveness. In fact, South Asia is lagging on several competitiveness indicators, such as attracting foreign investments, penetrating new markets and diversifying and upgrading its export products. In addition, trade openness and regional integration remains limited. Tackling these structural issues in a comprehensive manner, with an emphasis on building productive capacities, is crucial to improve the medium-term growth and to make visible progress towards sustainable development.

Western Asia: Slow but steady growth in intraregional trade

The pattern of international trade flows in Western Asian economies changed only slightly in 2017 from the previous year. The share of the region’s trade with East and South Asia remained the largest, with 49 per cent of exports and 33 per cent of imports. The share of trade with the EU remained the second largest, with 20 per cent of exports and 31 per cent of imports. Meanwhile, intraregional trade has grown at a moderate but steady pace from 9 per cent in 2000 to 13 per cent in 2017. The consistent growth is in part attributed to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) customs union, which became effective in 2015. Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates dominated the level of intraregional trade flows although their trading partners are more geographically diversified. According to official data, Turkish exports to Syria stood at $1.36 billion in 2017, having recovered to 74 per cent of the 2010 level. However, the Syrian crisis continued to weigh on exports from Jordan and Lebanon due to the ongoing closure of the Syrian-Jordan border points to commercial traffic.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Stronger demand in South America and reduction of trade-restrictive measures stimulate intraregional trade

Amid a broad-based upturn in global economic activity, export growth in Latin America and the Caribbean has gradually picked up over the past two years. In 2017, the region’s exports of goods and services grew by an estimated 2.1 per cent in real terms, slightly faster than in 2016, but still well below the 2000–2015 average of 3.7 per cent. Export growth has been driven by strong demand from China and the ASEAN countries, especially for metals (copper, iron ore) and agricultural products (soybean, wheat). A modest recovery of demand in South America, along with a reduction of trade-restrictive measures in recent years, has helped stimulate intraregional trade. Since late 2015, Argentina has lifted both tariff and non-tariff restrictions. Ecuador gradually eliminated the import surcharges that were imposed in 2015 to address the country’s deteriorating balance of payments situation. In addition, the Mercosur members (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) signed in mid-2017 a trade agreement with Colombia that allows limited quantities of tariff-free trade in products, including automobiles, textiles and agrochemicals. One of the main beneficiaries of more dynamic intraregional trade has been Brazil’s automotive industry. In 2017, the total number of exported vehicles increased by 48 per cent to an all-time high of 766,000 units, with much of the growth coming from Argentina and Colombia. While intraregional trade will likely continue to improve in 2018–2019, there is a need to deepen regional economic integration in order to boost trade in manufactured and higher value-added goods. Currently intraregional exports account for only 17 per cent of the region’s total exports. This is well below the peak level of 22 per cent reached in 1994 and much lower than the levels seen in the EU (62 per cent) and in East and South-East Asia (about 50 per cent).

Launch of WESP mid-2018

The World Economic Situation and Prospects as of mid-2018 will be launched on 17 May at 11 am in New York by Assistant-Secretary-General for Economic Development and Chief Economist, Elliott Harris, and DESA’s Chief of the Global Economic Monitoring Branch, Dawn Holland. The launch will be broadcast live via UN Web TV. The full report will be available on 17 May at http://bit.ly/wespreport.

Follow Us