World Economic Situation And Prospects: March 2019 Briefing, No. 124

- Growing demand for leveraged loans may pose a new global financial risk

- Surge in African sovereign external bond issuance raises concern

- China’s recent policy easing may further increase the domestic debt level

English: PDF (198 kb)

Global issues

The recent upsurge in leveraged loans—financial risks and productivity implications

As discussed in the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019, high indebtedness has become a critical feature of the global economy. In the last decade, debt levels have risen visibly across countries and sectors, fuelled by ultra-loose monetary policies in major economies. Public and private debt have reached historical highs in many countries. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the global debt stock is nearly one-third higher than in 2008 and more than three times global gross domestic product (GDP).

Amid signs that global growth has peaked and with renewed uncertainties over the monetary policy trajectory of the United States Federal Reserve (Fed), high global debt is not only a financial risk in itself but also a source of vulnerability in case of a downturn. A faster-than-expected increase in interest rates and a sudden rise in global financing costs pose risks to debt and financial stability. While high levels of corporate debt can amplify an economic downturn, high sovereign debt constrains fiscal policy space, hindering the policy response and potentially delaying the recovery. These aspects are especially relevant as global growth has been heavily dependent on extraordinary monetary policy easing and short-term expectations of rising asset values. This has exacerbated financial risks by reinforcing search-for-yield behaviour and by encouraging financial activities, such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and share buy-backs, rather than productive investments.

Against this backdrop, the ongoing rise of leveraged loans in several developed countries is increasingly seen as a potential risk for financial stability. The term “leveraged loans” is used to describe syndicated loans at floating interest rates provided to firms that already have high levels of debt relative to earnings and poor credit standards. After collapsing during the global financial crisis, leveraged loans have recently resurged in the United States of America and Europe, especially in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The current total size of the global leveraged loan market is about $1.3 trillion, more than twice the size a decade ago. In the United States, it exceeds the size of the high-yield corporate bond market.

Against this backdrop, the ongoing rise of leveraged loans in several developed countries is increasingly seen as a potential risk for financial stability. The term “leveraged loans” is used to describe syndicated loans at floating interest rates provided to firms that already have high levels of debt relative to earnings and poor credit standards. After collapsing during the global financial crisis, leveraged loans have recently resurged in the United States of America and Europe, especially in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The current total size of the global leveraged loan market is about $1.3 trillion, more than twice the size a decade ago. In the United States, it exceeds the size of the high-yield corporate bond market.

The rise in leveraged loans has been encouraged by investors’ search for yield and, more recently, the prospects for higher interest rates. In 2017 and 2018, the global issuance of leveraged loans reached pre-crisis levels of close to $700 billion per annum (see figure 1). The expansion in leveraged lending has been facilitated by increased securitization through collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), a financial instrument where payments from multiple firms are pooled together and then sold to investors in various tranches. Recent shifts in enforcement procedures for lending guidelines in the United States have made it easier for banks to place different tranches of CLOs in the market. At the same time, highly-indebted firms are attracted to this type of financing, which is generally more flexible than bonds.

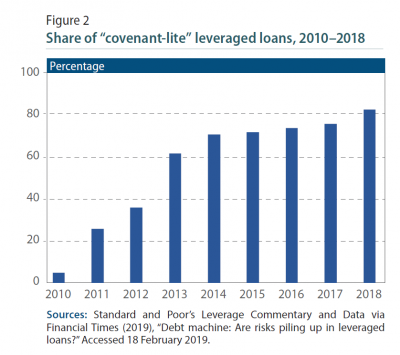

There are growing concerns regarding the build-up of risks in the leveraged loan market and implications for financial stability in case of a sudden shift in investor sentiment. Rising investor demand, coupled with an increasing number of firms willing to take on more debt, has led to a deterioration in the underwriting standards and the credit quality of these loans. For example, the share of the so-called “covenant-lite” leveraged loans—where investors do not require borrowers to maintain certain financial ratios—has risen continuously in recent years, reaching record highs of about 80 per cent (figure 2). In addition, most of the new issuances of leveraged loans have been used to engineer changes in firms’ liability structures, rather than funding new productive investments. Finally, the leverage of borrowers has also increased recently. For example, the proportion of leveraged loans issued to firms with debt-to-earnings ratios at or above 6 reached about 30 per cent in 2018, the highest level since before the global financial crisis. This shows the rising risk tolerance of investors in the market for corporate debt. Notably, these trends in leveraged lending contain similarities to the pre-crisis subprime mortgage market.

Amid rising corporate leverage and lower credit quality, slower economic growth and higher interest rates can substantially increase firms’ difficulties in rolling over debt. A rise in bankruptcies, credit defaults and mark-to-market losses can induce fire sales and trigger a downward spiral in prices and a liquidity crunch. Given the highly interconnected financial system, this could have wider financial and economic implications. Yet, unlike in the case of subprime mortgages before the crisis, leveraged loans today do not have significant volumes of re-securitization (“securitizations of securitizations”). They also contain a certain degree of protection for investors, as they are near the top of the credit structure, secured by firms’ assets. In addition, the banking system is better prepared to contain broader financial spillovers than it was prior to the global financial crisis, with better capitalization of banks and less reliance on short-term funding. Thus, while leveraged lending may not trigger a widespread financial meltdown, it can certainly deepen an economic downturn, especially considering its growing relevance to fund M&As, pay dividends and buy back shares.

Amid rising corporate leverage and lower credit quality, slower economic growth and higher interest rates can substantially increase firms’ difficulties in rolling over debt. A rise in bankruptcies, credit defaults and mark-to-market losses can induce fire sales and trigger a downward spiral in prices and a liquidity crunch. Given the highly interconnected financial system, this could have wider financial and economic implications. Yet, unlike in the case of subprime mortgages before the crisis, leveraged loans today do not have significant volumes of re-securitization (“securitizations of securitizations”). They also contain a certain degree of protection for investors, as they are near the top of the credit structure, secured by firms’ assets. In addition, the banking system is better prepared to contain broader financial spillovers than it was prior to the global financial crisis, with better capitalization of banks and less reliance on short-term funding. Thus, while leveraged lending may not trigger a widespread financial meltdown, it can certainly deepen an economic downturn, especially considering its growing relevance to fund M&As, pay dividends and buy back shares.

The recent expansion of leveraged loans could also have implications for productivity growth. While these loans provide an important source of financing for firms undergoing temporary economic and financial difficulties, they can also keep poorly managed and low-productivity firms in the market. This can prevent a more dynamic and efficient reallocation of resources, thus constraining productivity growth. The prevalence of so-called “zombie firms”—firms with persistent problems in meeting their interest payments obligations—has continuously increased in developed countries in recent years. While it is difficult to establish a direct connection between leveraged loans and productivity growth, recent evidence shows that reduced financial pressure and lower interest rates are associated with a higher prevalence of such firms. More broadly, while the observed slowdown in productivity growth has been mainly linked to factors such as technological change, demography and trade, the role of monetary policy deserves further attention. To manage future crises, it is critical to better understand the short- and medium-term implications of ultra-loose monetary policies for the corporate sector.

Developed economies

United States: Almost one third of fiscal spending is not covered by receipts

Many developed economies continue to face the challenge of dealing with very high or rising debt levels. In the United States, the federal budget deficit reached 29 per cent of outlays in the first quarter of the current fiscal year (October–December 2018), compared to 23 per cent in the previous year. Total receipts increased by 0.2 per cent, with revenue from corporate income taxes falling by almost 15 per cent and from individual income taxes by 4.2 per cent, as a consequence of the tax cuts initiated in 2018. This was offset by higher revenue from payroll taxes, excise taxes and customs duties, following the introduction of various tariffs. Total outlays increased by 9.6 per cent, driven by sharply higher interest payments and increases in spending on military and social security.

These quarterly trends have important implications for the fiscal outlook. First, at a time of a booming economy with record-low unemployment, almost 30 per cent of federal outlays are not covered by receipts. This leaves the economy on track to add more than 6 per cent of GDP to its total debt by the end of the fiscal year. In case of an economic slowdown or recession, the resulting decline in revenues and increase in spending could cause a further sharp increase in both ratios. Second, a large part of the current federal budget consists of mandatory spending on entitlement programs, which will likely further increase in the future. Demographic factors will drive social benefit payments higher in the coming years. In addition, with interest rates rising from historically low to more normal levels, the cost of covering future budget shortfalls and refinancing previous ones will steadily increase under current trends. Rising interest rates, combined with the existing stock of debt and continuous high financing needs, will likely further increase spending just to finance the outstanding public debt.

Japan: Fiscal position to improve only gradually

The size of Japan’s central government budget is expected to surpass 100 trillion yen ($902 billion) in the fiscal year 2019/20. While a slight increase of tax revenues is projected as a result of a planned hike in the consumption tax rate from 8 per cent to 10 per cent in October 2019, 32 per cent of the total budget is to be financed through bond issuance. While this share has come down from a peak of 52 per cent in 2009, the fiscal position is projected to improve only gradually. The Government aims to achieve a primary surplus by 2026. However, according to projections made by the Cabinet Office in July 2018, achieving this target is conditional on maintaining an annual rate of real GDP growth of about 2 per cent. Given that the level of gross public debt, including from local governments, is expected to have reached 200 per cent of GDP in 2018, Japan’s fiscal situation remains highly challenging.

Europe: Fiscal policy space remains limited

In Europe, policymakers face the challenge of limited policy space, largely stemming from a confluence of fiscal and monetary policy factors. In the wake of the global financial crisis, countries followed a path of procyclical fiscal consolidation, relying on monetary policy to stimulate economic activity. Monetary policymakers repeatedly emphasized the need for individual countries to complement the extremely accommodative monetary stances with structural reforms to revitalize their economies. Today, with a turn in monetary policy imminent, the window of opportunity provided by the extraordinarily loose monetary policy stance to undertake far-reaching economic reforms is starting to close. In many cases, countries still find themselves in fundamentally challenging fiscal positions: Belgium, Greece, Italy and Portugal have public debt-to-GDP ratios above 100 per cent, while in Cyprus, France and Spain, the ratio is only slightly under 100 per cent. These elevated debt levels, the prospect of rising interest rates and higher debt servicing costs, and the European Union (EU) budget rules on debt levels and deficits all serve to limit the scope for fiscal policy to offset the withdrawal of monetary stimulus. These conditions also leave limited policy options in case of a renewed slowdown. In one scenario, the task of managing the economy would again fall to monetary policymakers. In the other scenario, national Governments could respond to a renewed slowdown by pursuing more expansionary fiscal policy. However, in many cases, this would be inconsistent with EU rules and could test the tolerance of financial markets for further increases in debt levels.

In South-Eastern Europe, despite years of prudent fiscal policy aimed at reducing budget deficits and public debt levels, infrastructure investment, financed by loans from China, has inflated some countries’ public debt. In particular, Montenegro’s general government gross debt exceeded 70 per cent of GDP in 2018. In response, the Government lifted indirect taxes and partially froze public sector salaries to reduce debt to below 60 per cent of GDP by 2020.

Economies in transition

CIS: Public finances in the Russian Federation remain stable

Among the economies of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Russian Federation has been maintaining a relatively low level of public debt since 2006, partly owing to persistent current account surpluses. At the end of 2017, the ratio of public debt to GDP stood at about 12.6 per cent. However, indebtedness of some regional governments remains a concern. Recent policies, including adoption of the fiscal rule, have further strengthened public finances. In early February, Moody’s raised the country’s sovereign rating to investment grade. Public borrowing needs are modest and even if the United States imposes further sanctions targeting Russian sovereign debt, the required funds may be raised domestically. In addition, total external debt of the Russian Federation has been shrinking since 2014, when access to foreign financial markets was curtailed by international sanctions and fell to a 10-year low of around $450 billion. At the same time, the country has accumulated massive sovereign international assets, which can serve as a cushion against external shocks. By contrast, some CIS energy-importers, including Belarus and Ukraine, are struggling with relatively high levels of public debt (over 70 per cent of GDP in the case of Ukraine) and the external debt repayment schedule for 2019–2020, limiting their fiscal space. For some of the smaller CIS economies such as Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, the rapid rise in public and external debt since 2014 may pose medium-term risks.

Developing economies

Africa: Surge in African sovereign external bond issuance raises concern

Active external bond issuances by Governments in Africa are projected to continue. Five countries (Angola, Egypt, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya and Morocco) are likely to tap international capital markets in the first half of 2019. In 2018, eight African countries raised $28 billion in total through external bond issuances. These sovereign bonds were popular among international investors, who maintained “search-for-yield” attitudes despite rising US dollar interest rates. External borrowing can support African economies to mobilize financial resources for much-needed investments. Moreover, as recent external bond issuances aim at longer maturities (up to 30 years), finance costs can be relatively low in net present value. However, the recent surge in external bond issuances has also raised debt sustainability concerns, particularly given the borrowers’ exposure to currency risk.

A case in point is Angola, where the Government raised $3.5 billion in external bond issuances in 2018 and public debt is estimated to have reached 91 per cent of GDP. According to the National Debt Plan, up to $2 billion will be financed by external bond issuances in 2019. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently assessed Angola’s public debt as sustainable, contingent on the Government’s commitment to fiscal reforms, including the introduction of a value-added tax (VAT) in July 2019, and a national economic development plan that focuses on economic diversification. However, the situation remains challenging as 48 per cent of total expenditure in the 2019 budget is assigned to service the outstanding debt, while volatile oil prices continue to impact revenues. Angola’s public debt sustainability thus depends on a sensitive balance of institutions, policy reforms, progress in economic diversification and external factors, especially in oil market fluctuations.

East Asia: China’s recent policy easing measures may fuel a further rise in domestic debt

In the fourth quarter of 2018, China’s GDP growth moderated to 6.4 per cent, its slowest pace since 1990. Growth in the services sector weakened, particularly in the real estate and the retail and wholesale trade subsectors. Amid strong domestic and external headwinds, concerns over the risk of a sharp slowdown of China’s economy have increased.

In recent months, the Chinese authorities have introduced a range of monetary and liquidity measures to support growth. In January, the central bank reduced bank reserve requirement ratios for the fifth time in a year. Earlier, it had also raised bank lending quotas, particularly lending to small and micro enterprises, in efforts to stimulate credit growth. In addition, restrictions on local government bond issuances have been eased to boost infrastructure investment.

While these measures are likely to provide support to short-term growth, they may further increase the already high domestic debt levels. Data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) show that non-financial corporate debt in China reached 155 per cent of GDP in the second quarter of 2018. Given slowing growth and high external uncertainty, there is an increased risk of a disorderly deleveraging process in the future, with potential large repercussions on real economic activity.

South Asia: Public debt levels are elevated, but appear sustainable

General government gross debt-to-GDP ratios across South Asia remain lower than among developed economies, ranging mostly from 40 to 50 per cent. Over the past decade, the indebtedness has generally gone up. The Islamic Republic of Iran recorded the largest increase, from 5 per cent of GDP to 49 per cent. This change mostly reflects the sharp drop in oil prices in 2014–2016 and the unilateral economic measures imposed on the country. Maldives and Pakistan both recorded a 17-percentage point increase in government debt-to-GDP ratios.

The general government debt-to-GDP ratio remains relatively high in India, although the ratio has fallen from a peak of 85 per cent in 2003 to 69 per cent in 2018. Comparing India’s present debt profile with China’s debt profile in 2000—the year when it reached India’s current per capita income level of $2,000 (in constant 2012 USD)—shows key differences in the two countries’ financing paths. While China’s general government debt-to-GDP ratio in 2000 was only 22 per cent of GDP, its combined government and private non-financial sector debt stood at 128 per cent of GDP—about the same ratio as in India today (125 per cent of GDP). The lower level of India’s private sector debt partly reflects a less developed financial sector, including a limited corporate debt market and an ongoing lack of financial inclusion. Given India’s GDP per capita growth of around 6 per cent, debt sustainability is currently not a main concern. However, fiscal pressures may rise over the coming decade due to immense infrastructure investment needs.

Western Asia: Weak oil prices compel oil-exporting countries to expand debt financing

The slump in oil prices since 2014 has changed the fiscal stances of the region’s major crude oil producers, namely member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). While diversifying revenue sources by introducing VAT, GCC countries also utilize more debt financing options to make up for fiscal shortfalls. In Saudi Arabia, the level of public debt has risen rapidly from 1.6 per cent of GDP in 2014 to an estimated 18 per cent in 2018. Despite the pressures on fiscal balances, GCC countries maintained spending growth in health, education and infrastructure, which are deemed essential for sustainable development through economic diversification.

Part of the region’s growing fiscal needs have been financed by issuance of Sukuk, Shari’a-compliant securities. Since Islamic principles forbid the payment of interest, the returns on Sukuk are tied to the profits generated by the underlying tangible assets. In the case of sovereign Sukuk issued by Governments, the underlying assets are likely related to public projects. Saudi Arabia issues domestic Sukuk monthly, raising 7 billion Saudi Riyal (SAR), equivalent to $1.8 billion, in January and SAR 9.4 billion ($2.5 billion) in February 2019. In international capital markets, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are projected to be active in Sukuk issuances. Outside Western Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia are also active issuers of Sukuk. In February, Indonesia completed an innovative global green Sukuk issuance, raising $2 billion.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Amid fiscal pressures, Brazil’s Government proposes pension reform

Although Brazil’s budget deficit narrowed slightly last year, the country’s fiscal adjustment needs remain large. The central government primary deficit (before interest payments) is estimated to have declined from 1.9 per cent of GDP in 2017 to 1.7 per cent in 2018. Gross public debt currently stands at 76.7 per cent of GDP—almost 30 percentage points higher than five years ago. Government revenues in 2018 were boosted by an 8 per cent increase in tax receipts as the economy recovered and the labour market strengthened. A growing surplus in the treasury balance was, however, offset by a widening social security deficit, which imposes an ever-increasing fiscal burden. In response, Brazil’s new Government is currently finalizing a pension reform proposal, including the introduction of a minimum retirement age, that will be sent to Congress for approval.

Jamaica has made significant strides in putting public debt back on a sustainable path. For six consecutive years, the country registered a primary surplus of more than 7 per cent of GDP. As a result, the public debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen from 147 per cent in 2013 to an estimated 97 per cent in 2018, the lowest level in almost two decades. This fiscal adjustment has been accompanied by improved macroeconomic stability and a gradual decline in unemployment. Jamaica’s positive experience of the past few years can serve as an example for other Caribbean economies facing strong fiscal pressures, such as Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados and Dominica. In Barbados, the Government’s reform program under the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility aims to achieve a primary surplus target of 6 per cent of GDP in 2019/20.

Follow Us