World Economic Situation And Prospects: July 2018 Briefing, No. 116

- Rising levels of public debt fueling fiscal sustainability concerns in many developing countries

- Several countries highly vulnerable to a sharp increase in government interest burden in the event of a financial shock

- High debt service obligations limit the availability of resources to pursue development objectives

English: PDF (168 kb)

Global issues

Rising fiscal vulnerabilities posing risk to development prospects in many developing countries

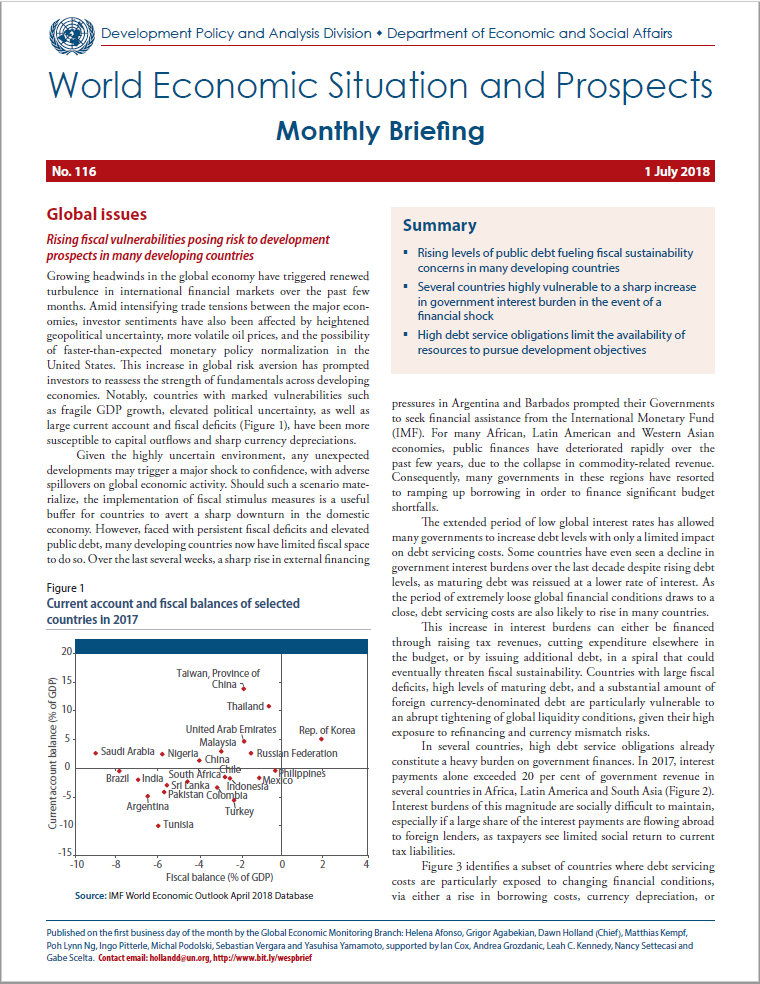

Growing headwinds in the global economy have triggered renewed turbulence in international financial markets over the past few months. Amid intensifying trade tensions between the major economies, investor sentiments have also been affected by heightened geopolitical uncertainty, more volatile oil prices, and the possibility of faster-than-expected monetary policy normalization in the United States. This increase in global risk aversion has prompted investors to reassess the strength of fundamentals across developing economies. Notably, countries with marked vulnerabilities such as fragile GDP growth, elevated political uncertainty, as well as large current account and fiscal deficits (Figure 1), have been more susceptible to capital outflows and sharp currency depreciations.

Given the highly uncertain environment, any unexpected developments may trigger a major shock to confidence, with adverse spillovers on global economic activity. Should such a scenario materialize, the implementation of fiscal stimulus measures is a useful buffer for countries to avert a sharp downturn in the domestic economy. However, faced with persistent fiscal deficits and elevated public debt, many developing countries now have limited fiscal space to do so. Over the last several weeks, a sharp rise in external financing pressures in Argentina and Barbados prompted their Governments to seek financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). For many African, Latin American and Western Asian economies, public finances have deteriorated rapidly over the past few years, due to the collapse in commodity-related revenue. Consequently, many governments in these regions have resorted to ramping up borrowing in order to finance significant budget shortfalls.

Given the highly uncertain environment, any unexpected developments may trigger a major shock to confidence, with adverse spillovers on global economic activity. Should such a scenario materialize, the implementation of fiscal stimulus measures is a useful buffer for countries to avert a sharp downturn in the domestic economy. However, faced with persistent fiscal deficits and elevated public debt, many developing countries now have limited fiscal space to do so. Over the last several weeks, a sharp rise in external financing pressures in Argentina and Barbados prompted their Governments to seek financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). For many African, Latin American and Western Asian economies, public finances have deteriorated rapidly over the past few years, due to the collapse in commodity-related revenue. Consequently, many governments in these regions have resorted to ramping up borrowing in order to finance significant budget shortfalls.

The extended period of low global interest rates has allowed many governments to increase debt levels with only a limited impact on debt servicing costs. Some countries have even seen a decline in government interest burdens over the last decade despite rising debt levels, as maturing debt was reissued at a lower rate of interest. As the period of extremely loose global financial conditions draws to a close, debt servicing costs are also likely to rise in many countries.

This increase in interest burdens can either be financed through raising tax revenues, cutting expenditure elsewhere in the budget, or by issuing additional debt, in a spiral that could eventually threaten fiscal sustainability. Countries with large fiscal deficits, high levels of maturing debt, and a substantial amount of foreign currency-denominated debt are particularly vulnerable to an abrupt tightening of global liquidity conditions, given their high exposure to refinancing and currency mismatch risks.

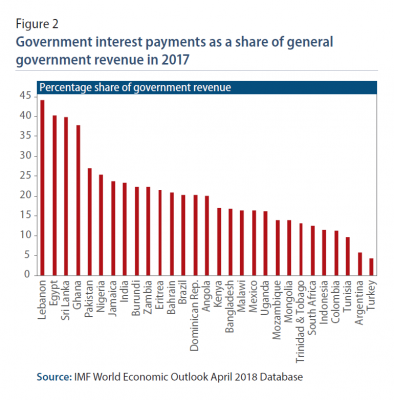

In several countries, high debt service obligations already constitute a heavy burden on government finances. In 2017, interest payments alone exceeded 20 per cent of government revenue in several countries in Africa, Latin America and South Asia (Figure 2). Interest burdens of this magnitude are socially difficult to maintain, especially if a large share of the interest payments are flowing abroad to foreign lenders, as taxpayers see limited social return to current tax liabilities.

Figure 3 identifies a subset of countries where debt servicing costs are particularly exposed to changing financial conditions, via either a rise in borrowing costs, currency depreciation, or commodity price shock. These diagnostic scenarios are presented in isolation, but should be interpreted in light of the close interaction between financial variables. For example, the collapse in oil prices by more than 50 per cent between 2014 and 2016 was associated with a 35 per cent devaluation of the Nigerian naira. This in turn triggered a 3 percentage point rise in interest rates, thus compounding the impact on the interest burden of the commodity shock with both an exchange rate and interest rate shock. A number of least developed countries (LDCs) and heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs) are identified as being particularly vulnerable to financial shocks. Many low-income countries have experienced a substantial rise in both fiscal and interest burdens in recent years, placing them at high risk of debt distress.

Figure 3 identifies a subset of countries where debt servicing costs are particularly exposed to changing financial conditions, via either a rise in borrowing costs, currency depreciation, or commodity price shock. These diagnostic scenarios are presented in isolation, but should be interpreted in light of the close interaction between financial variables. For example, the collapse in oil prices by more than 50 per cent between 2014 and 2016 was associated with a 35 per cent devaluation of the Nigerian naira. This in turn triggered a 3 percentage point rise in interest rates, thus compounding the impact on the interest burden of the commodity shock with both an exchange rate and interest rate shock. A number of least developed countries (LDCs) and heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs) are identified as being particularly vulnerable to financial shocks. Many low-income countries have experienced a substantial rise in both fiscal and interest burdens in recent years, placing them at high risk of debt distress.

Faced with increasing risks of sovereign rating downgrades and sharply higher borrowing costs, high debt levels also intensify fiscal consolidation pressures, undermining governments’ capacities and political will to pursue development objectives. Any cutback or delays to critical infrastructure investment will worsen existing structural bottlenecks and constrain productivity growth, further hampering the progress towards sustainable development. In addition, rollbacks on policy measures to address structural challenges, including measures to tackle high unemployment and rising inequality, could risk triggering political and social unrest.

In the current environment, policymakers in the developing economies need to assess policy options not only to effectively mitigate external risks, but also to restore fiscal positions to a more sustainable footing. For the commodity-dependent economies, the present fiscal challenges highlight the urgent need to accelerate economic diversification efforts and diversify sources of government revenue. Measures to improve fiscal management are also important in strengthening public finances and preserving confidence. These measures could include improving the allocation of expenditure, expanding the tax base, and ensuring that public debt is channelled towards productive investment.

Developed economies

United States: Procyclical fiscal stance exposes vulnerabilities in developing countries

The expansive fiscal stance of the United States sets it apart from most other developed countries, where Governments have tended to adopt a broadly neutral fiscal policy stance for 2018–2019. Recent fiscal stimulus measures are expected to add roughly 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in 2018, while significantly increasing the public deficit and debt. With the economy operating close to full employment and inflation at the central bank’s target, the fiscal expansion is highly procyclical, and may accelerate the pace of interest rate rises by the Federal Reserve. An associated tightening of global liquidity conditions would have significant repercussions for many of the vulnerable developing countries discussed above.

Japan: Narrowing fiscal space poses policy dilemma

Narrowing fiscal space poses a policy dilemma for Japan, given that it has almost exhausted monetary policy options with its extraordinarily loose monetary stance. With gross public debt at 236 per cent of GDP in 2017, the Government has repeatedly pledged to undertake more effective fiscal consolidation, including the planned hike in the sales tax rate in October 2019. However, the Government is also cautious not to derail the fragile growth in domestic demand. For the fiscal year 2018, only a modest increase in expenditure, mostly on social security spending, has been budgeted. However, should the economy experience an unexpected slowdown, additional spending is likely.

Europe: A less stringent fiscal policy stance

Fiscal policy is expected to have a broadly neutral impact on growth in 2018–2019. A number of countries, including Austria and Germany, continue to require fiscal spending increases to integrate the large number of migrants. However, fiscal space remains limited in the EU as a whole. The region’s aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 86 per cent while Belgium, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal have debt-to-GDP ratios around or in excess of 100 per cent. While the currently low level of interest rates reduces the cost of debt service, the shift in monetary policy stances towards a normalization of interest rates hints at higher levels of fiscal spending on servicing public debt in the near future. In the United Kingdom, the budget deficit decreased from 3.0 per cent of GDP in 2016 to 1.9 per cent of GDP in 2017, due to higher tax revenue and spending reductions. However, fiscal policy will remain under pressure from the effects created by the decision to leave the EU. The United Kingdom has to reorganize public support mechanisms and financial flows in a plethora of policy areas, and this administrative exercise alone is already a major cost.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Conservative fiscal policy of energy-exporters despite higher oil prices

For several economies in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), including Kazakhstan, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan and Ukraine, banking sectors bailouts in 2017 have exerted significant pressure on public finances. However, the recent rise in oil prices has alleviated some of the fiscal constraints faced by the CIS energy-exporters since 2014.

Fiscal policy in the Russian Federation remains conservative, due to the implementation of a fiscal rule designed to decrease reliance on hydrocarbon revenues, to rebuild the National Wealth Fund, and to curtail currency volatility. The possibility of new sanctions targeting Russian sovereign debt is reinforcing fiscal conservatism. However, progress towards the recently announced economic development targets and social spending promises requires raising additional revenue. The Government has proposed an increase in the value-added tax (VAT) rate in 2019 and a gradual increase in the retirement age. Among other large energy-exporting economies in the region, Kazakhstan aims to preserve fiscal sustainability through the phasing out of earlier stimulus measures, thus reducing the budget and the non-oil deficits in 2018 to 1.1 and 7.4 per cent of GDP. Meanwhile, Turkmenistan is consolidating public finances after large infrastructure spending in 2017.

Among the CIS energy-importers, fiscal policy in Ukraine is coordinated with the IMF. Public debt must be reduced to 71 per cent of GDP by 2020. Thanks to improving economic conditions, the leverage of the IMF over economic policy is weakening; the successful issuance of Eurobonds in 2017 raised $3 billion and reduced dependence on external funding. This has allowed some fiscal loosening, including doubling the minimum wage in 2017 and plans to increase pensions. Due to the internal conflict, defence spending remains significant. For the smaller CIS economies, higher growth, increasing remittances and stronger consumption have boosted fiscal revenues.

Developing economies

Africa: Aggregate fiscal deficit improved in 2015–2017

In 2014–2015, most economies in Africa were hard hit by the commodity downturn. The drop in commodity revenue led to a deterioration of fiscal positions and sharp rise in government debt. The debt-to-GDP ratio for the continent rose from less than 40 per cent of GDP in 2013 to reach more than 50 per cent of GDP in 2017. As fiscal deficits remain high in most regions, debt levels are unlikely to recede significantly in the near term.

Africa’s overall fiscal deficit in 2017 improved compared to 2016, but still stood at more than 6 per cent of GDP. The improvement was mainly due to increased revenues connected to higher commodity prices, although expenditures for the continent as a whole also decreased marginally relative to GDP. Looking forward, Africa’s fiscal deficit should continue to improve slightly in 2018 and 2019.

North Africa ran a large fiscal deficit of close to 9 per cent of GDP in 2017, which weighed heavily on the continental average. This largely reflects Egypt’s high deficit and the exceptional situation in Libya. Excluding Egypt and Libya, the fiscal deficit in North Africa averaged 4.7 per cent in 2017, and was more closely aligned with other regions. Deficits in East, West and Southern Africa averaged 4.5-5.5 per cent of GDP in 2017.

In Central Africa, after a sharp increase peaking at 8.1 per cent of GDP in 2015, fiscal deficits are improving and will rank among the lowest in 2018/2019 at just 0.3/0.1 per cent of GDP, thanks to firmer oil prices and international support.

East Asia: Policymakers in several countries are utilizing available fiscal space to address medium-term issues

With the recent escalation in trade tensions and spikes in global financial market volatility, downside risks to East Asia’s short-term growth outlook have increased. However, in the event of an external shock, most countries in the region have some degree of fiscal space to support domestic economic activity. Compared to other developing regions, fiscal positions in East Asia are relatively stronger, attributed in part to robust GDP growth and more prudent fiscal management. Over the past five years, fiscal deficits in the region averaged only 1.8 per cent, while the region’s public debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low, amounting to 46 percent of GDP in 2017.

Nevertheless, there is still ample room to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public expenditure among East Asian economies. Efforts to mobilize more fiscal resources towards addressing the region’s development challenges are crucial in order to strengthen economic resilience and improve the quality of growth. Over the past year, several governments in the region have announced a range of measures aimed at boosting productivity growth and expanding social protection systems. Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand have continued to focus on developing transport infrastructure to improve connectivity. The Indonesian Government has also announced plans to prioritize human capital development, through the expansion of vocational training and apprenticeship programmes. Meanwhile, in the Republic of Korea, the authorities plan to raise spending on welfare, including increasing social service jobs and expanding health insurance coverage.

South Asia: Weak fiscal positions a key policy challenge

The strengthening of fiscal accounts is a major medium-term policy challenge in South Asia. Most economies have high government debt-to-GDP and low tax-to-GDP ratios in comparison to other developing regions. For instance, the public debt-to-GDP ratio is above 60 per cent in Maldives, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and interest payments are close to or exceed 20 per cent of government revenue in several economies. This severely constrains the capacity to implement countercyclical policies to stabilize and support domestic demand and to deploy redistributive interventions to promote more inclusive development. Thus, South Asia should intensify efforts to widen the tax base, strengthen the design and administration of tax systems and eliminate channels for tax avoidance and evasion, while promoting a supportive environment for the private sector.

Against this backdrop, fiscal policies are officially in a moderately tight stance across the region. However, the ongoing consolidation efforts have been flexible. Thus, fiscal deficits are likely to remain elevated—even more so given the prospect for national elections in several countries—but manageable in the near term. For example, the fiscal deficit in India continues to be above official targets, about 3.5 per cent over GDP. In Pakistan, the fiscal deficit has recently increased, due to rising expenditures to tackle development needs and high repayment debt obligations. The fiscal deficit in Bangladesh remains high, close to 5.0 per cent over GDP. However, tax revenues should strengthen in the near term, due to vigorous economic growth as well as prospects for the introduction of a VAT in 2019. Meanwhile, progress in reducing the fiscal deficit in Sri Lanka has been slow, in part because of increased spending to mitigate the effects of natural disasters.

Western Asia: Jordan and Lebanon face fiscal reform challenges

Rising oil prices have improved the budget balances of oil exporters in Western Asia. For the fiscal year 2018, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are projected to register fiscal surpluses. Iraq is also benefiting from lower defence expenditures, amid a stabilizing security situation.

Meanwhile, Jordan is struggling with obtaining popular support for its fiscal reform plan. Its 2018 budget outlined several measures to raise government revenues by 18 per cent. The general sales tax was unified at 16 per cent, removing exemptions on food items. Subsidies on bread were also removed. The implementation of these measures contributed to the increase in consumer price inflation to 5.1 per cent in May. In response to proposed income tax reforms, Jordan witnessed public protests in June.

Lebanon is also facing challenges in its plan to increase government revenue. Due to high public debt and interest payments, Lebanon’s total budget deficit has been growing despite recording a primary budget surplus (which exclude interest payments) in recent years. In 2017, public debt stood at 155 per cent of GDP and interest payments consist of 36 per cent of total expenditure.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Fiscal adjustment remains a priority for many countries

Despite the recent recovery in global commodity prices and a slightly improved growth outlook, the fiscal situation in the region remains challenging. Except Jamaica, all countries in the region recorded fiscal deficits in 2017. While primary fiscal balances were positive in Mexico and several Central American countries, they remained negative in most of South America. Persistent fiscal deficits have led to a notable increase in government debt: the region’s public debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 48.5 per cent in 2013 to 60 per cent in 2017. Since January 2017, deteriorating fiscal situations have led to credit rating downgrades in several countries, including Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica. Faced with fiscal pressures and a fragile economic recovery, governments have mostly undertaken a process of gradual fiscal adjustment. In some cases, the pace of adjustment will likely have to increase going forward. This is especially true for Argentina and Brazil, which both face large fiscal imbalances and considerable macroeconomic vulnerabilities.

Argentina’s primary fiscal deficit stood at 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2017, virtually unchanged from 2015 and 2016. This deficit has been partly financed by foreign borrowing, causing a strong increase in dollar-denominated debt and creating large external financing needs. Following a recent currency turmoil, where international investors pulled money out of peso assets on a large scale, Argentina’s Government and the IMF agreed on a 36-month Stand-By Arrangement amounting to $50 billion. The associated economic plan aims at restoring primary balance by 2020, with a significant up-front adjustment.

Barbados has also requested financial assistance from the IMF, and suspended payments on debts owed to external commercial creditors. The Government has announced that it is seeking to restructure it public debt, which is among the highest in the world relative to GDP. Barbados is running a primary fiscal surplus, but carries an interest burden of 7.7 per cent of GDP, diverting resources from essential infrastructure investment and social safety nets.

In Brazil, a combination of moderate primary deficits and high interest expenditures has resulted in large overall fiscal deficits, averaging 9 per cent of GDP in 2015–2017. As a result, the public debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 60 per cent in 2013 to 84 per cent in 2017. Going forward, the country’s biggest fiscal challenge is reforming its pension system, which is seen as unsustainable. The combined deficit of the public and private pension system amounted to about 4 per cent of GDP in 2017. With a rapidly aging population and declining ratio of contributors to beneficiaries, Brazil’s fiscal pressures are projected to worsen in the coming decades.

Follow Us