World Economic Situation And Prospects: January 2019 Briefing, No. 122

- WESP 2019 highlights that economic progress remains highly uneven across the world

- Downside risks to the global growth outlook have increased

- Waning support for multilateralism may limit the capacity for collaborative policies in the event of a sharp global economic downturn

English: PDF (178 kb)

WESP 2019: Solid global growth obscures significant development challenges

The steady pace of expansion in the global economy masks an increase in downside risks that could potentially exacerbate development challenges in many parts of the world, cautioned the World Economic Situation and Prospects (WESP) 2019 report, launched today in New York.

The world economy is estimated to have grown by 3.1 per cent in 2018, as a fiscally induced growth acceleration in the United States of America offset a slower expansion in a few large economies, including Argentina, Canada, China, and Turkey. In many developed countries, growth rates have risen close to their potential, while unemployment rates have dropped to historical lows. Among the developing economies, the East and South Asia regions remain on a relatively strong growth trajectory, amid robust domestic demand conditions. While economic activity in the commodity-exporting countries, notably fuel exporters, is gradually recovering, growth remains susceptible to volatile commodity prices. For these economies, the sharp drop in global commodity prices in 2014/15 has continued to weigh on fiscal and external balances, while leaving a legacy of higher levels of debt.

Looking ahead, there are increasing signs that global growth may have peaked. Growth in global industrial production and merchandise trade volumes has been tapering since early 2018, particularly in the trade-intensive capital and intermediate goods sectors. In several countries, leading indicators point to some softening in economic momentum, amid escalating trade disputes, risks of financial stress and volatility, and an undercurrent of geopolitical tensions. At the same time, a few developed economies are facing capacity constraints, which may weigh on growth in the short term.

The WESP projects steady global growth of 3.0 per cent in 2019 and 2020 (Figure 1). As the impulse from fiscal stimulus wanes, the growth momentum in the United States is projected to slow from 2.8 per cent in 2018 to 2.5 per cent in 2019 and 2 per cent in 2020. While the European Union is projected to experience steady growth of 2.0 per cent, the risks are tilted to the downside, including a potential fallout from Brexit. In China, growth is expected to moderate from 6.6 per cent in 2018 to 6.3 per cent in 2019, with policy support partly offsetting the negative impact of trade tensions. Several large commodity-exporting countries, including Brazil, Nigeria and the Russian Federation, are likely to see a moderate pickup in growth in the outlook period, albeit from a low base.

The WESP projects steady global growth of 3.0 per cent in 2019 and 2020 (Figure 1). As the impulse from fiscal stimulus wanes, the growth momentum in the United States is projected to slow from 2.8 per cent in 2018 to 2.5 per cent in 2019 and 2 per cent in 2020. While the European Union is projected to experience steady growth of 2.0 per cent, the risks are tilted to the downside, including a potential fallout from Brexit. In China, growth is expected to moderate from 6.6 per cent in 2018 to 6.3 per cent in 2019, with policy support partly offsetting the negative impact of trade tensions. Several large commodity-exporting countries, including Brazil, Nigeria and the Russian Federation, are likely to see a moderate pickup in growth in the outlook period, albeit from a low base.

Economic growth is uneven, often not reaching the regions that need it most

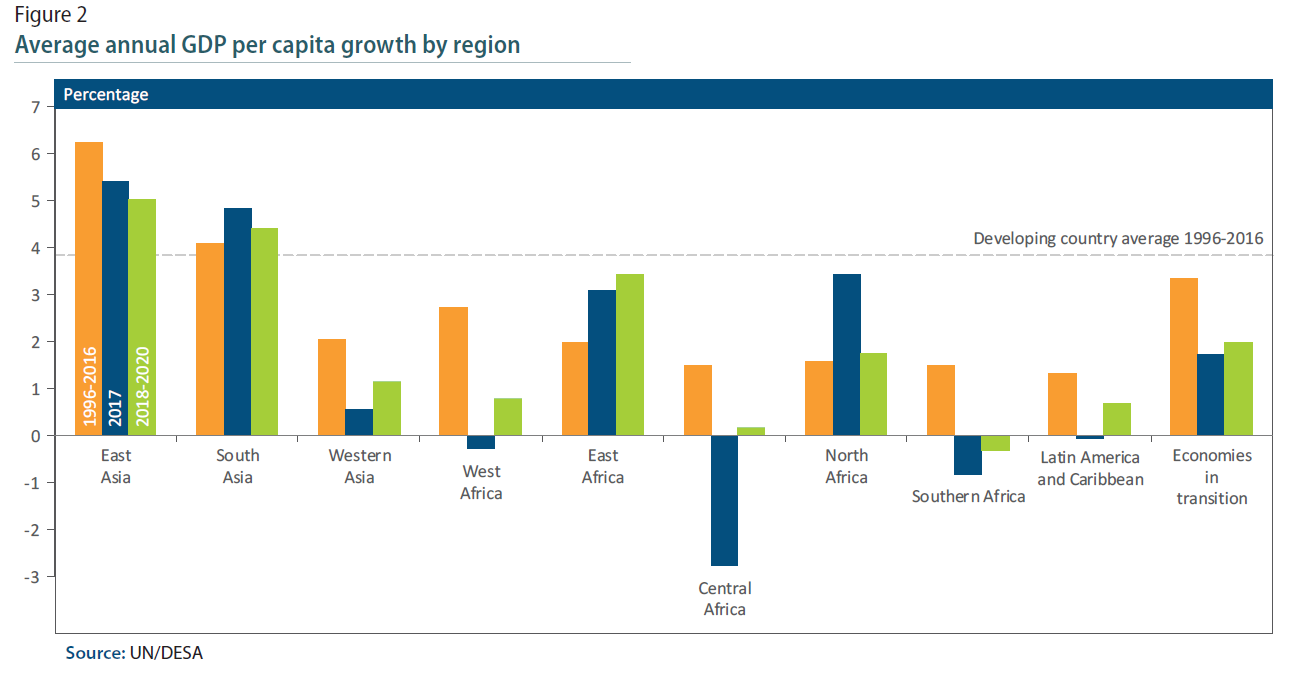

Beneath the strong global headline figures, however, economic progress has been highly uneven across regions. Despite an improvement in growth prospects at the global level, several large developing countries saw a decline in per capita income in 2018. While a modest recovery is projected in 2019, per capita incomes are still likely to remain stagnant or grow only marginally in Central, Southern and West Africa, Western Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 2). These regions are home to nearly a quarter of the global population living in extreme poverty. In the majority of the least developed countries (LDCs), per capita GDP growth remains significantly below the rates needed to eradicate extreme poverty.

Even among the economies that are experiencing strong per capita income growth, economic activity is often driven by core industrial and urban regions, leaving peripheral and rural areas behind. Despite historically low unemployment rates in several developed countries, many individuals, notably those with low incomes, have seen little or no growth in disposable income for the last decade.

Even among the economies that are experiencing strong per capita income growth, economic activity is often driven by core industrial and urban regions, leaving peripheral and rural areas behind. Despite historically low unemployment rates in several developed countries, many individuals, notably those with low incomes, have seen little or no growth in disposable income for the last decade.

Declining or inadequate income growth, coupled with high levels of inequality, poses an enormous challenge as countries strive to reduce poverty, develop essential infrastructure, and support economic diversification. Deep inequalities in income distribution also hamper progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 1 on poverty eradication. In Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean and Western Asia—three regions with historically high levels of inequality—some moderate progress has been made over the past two decades in reducing inequality. However, in Africa and in the LDCs, eradicating poverty by 2030 will require both double-digit GDP growth and dramatic declines in inequality, illustrating the scale of the current challenges faced.

Increasing downside risks and vulnerabilities pose considerable threats to the growth outlook

The global economy is facing a confluence of risks, which could severely disrupt economic activity and inflict significant damage on longer-term development prospects. These risks include an escalation of trade disputes, an abrupt tightening of global financial conditions, and intensifying climate risks.

Escalation of trade policy disputes

In 2018, the rise in trade tensions among the world’s largest economies was accompanied by a sharp increase in the number of disputes raised under the dispute settlement mechanism of the World Trade Organization. The United States’ decisions to increase import tariffs have sparked retaliations and counter-retaliations. A prolonged episode of heightened trade tensions and a spiral of additional tariffs poses a significant risk to the global growth outlook. Global economic activity would be impacted through several channels, including a slowdown in investment, higher consumer prices and a decline in business confidence. This would create severe disruptions to global value chains, particularly for the East Asian economies that are deeply embedded into the supply chains of trade between China and the United States. Slower growth in these two major countries would also reduce demand for commodities, affecting commodity-exporters in Africa and Latin America.

A protracted period of subdued trade growth would also weigh on productivity growth in the medium term, and hence on longer-term growth prospects. Trade supports productivity growth via economies of scale, access to inputs, and the acquisition of knowledge and technology. Trade in services also contributes to inclusiveness, resilience, and diversification. These channels are strongly intertwined with investment decisions, productivity gains, economic growth and ultimately sustainable development.

Abrupt tightening of global financial conditions

Financial markets experienced bouts of heightened volatility in 2018, as investor sentiments were affected by the increase in trade tensions, oil market developments, and shifting expectations over monetary policy in the United States. Against this backdrop, global financial conditions experienced some tightening during the year. In the current uncertain environment, any unexpected developments or sudden shift in sentiment could trigger sharp market corrections and a disorderly reallocation of capital.

Amid a highly pro-cyclical fiscal expansion and an increase in import tariffs, a strong rise in inflationary pressures could prompt the United States Federal Reserve to raise interest rates at a much faster pace than expected. In Europe, the possible failure of policymakers to finalize post-Brexit legal and regulatory arrangements before March 2019 poses additional risks to financial stability, given the prominence of European banks in driving global cross-border financial flows. Recent policy easing in China, while likely to support short-term growth, could exacerbate financial imbalances. This may raise the risk of a disorderly deleveraging process in the future, with large repercussions on real economic activity, with regional and global spillovers.

A rapid rise in interest rates and a significant strengthening of the dollar could exacerbate domestic fragilities and financial difficulties in some countries, leading to higher risk of debt distress. Across many developed and developing economies, public and private debt levels have risen to historical highs in the post-crisis period (Figure 3). In several countries, high debt service obligations already constitute a heavy burden on government finances. More broadly, the rise in debt in developing economies has generally not been matched by an equivalent expansion of productive assets. This raises concerns about debt sustainability, as well as concerns about productive capacity over the medium term, given large infrastructure gaps and degradation of existing capital.

A rapid rise in interest rates and a significant strengthening of the dollar could exacerbate domestic fragilities and financial difficulties in some countries, leading to higher risk of debt distress. Across many developed and developing economies, public and private debt levels have risen to historical highs in the post-crisis period (Figure 3). In several countries, high debt service obligations already constitute a heavy burden on government finances. More broadly, the rise in debt in developing economies has generally not been matched by an equivalent expansion of productive assets. This raises concerns about debt sustainability, as well as concerns about productive capacity over the medium term, given large infrastructure gaps and degradation of existing capital.

Intensifying climate risks

Over the last six years, more than half of extreme weather events have been attributed to climate change. Climate shocks impact developed and developing countries alike, putting large communities at risk of displacement and causing severe damage to vital infrastructure. Nevertheless, the human cost of disasters falls overwhelmingly on low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Many small island developing States (SIDS) are particularly exposed to climate risks, through flooding, rising aridity, coastal erosion and depletion of freshwater. Climate-related damage to critical transport infrastructure may have broader implications for international trade and for the sustainable development prospects of the most vulnerable nations.

While some progress has been made in reducing the greenhouse gas intensity of production, the transition towards environmentally sustainable production and consumption is not happening fast enough. A fundamental and more rapid shift in the way the world powers economic growth is urgently needed if we are to avert further serious damage to our ecosystems and livelihoods. Such a fundamental transformation requires policy action on many fronts, the acceleration of technological innovation, and significant behavioural changes.

The multilateral approach to global policy making is facing significant challenges

In today’s closely integrated world economy, internationally agreed rules are vital to ensure smoothly functioning markets and resolve disagreements. Strengthening multilateralism is therefore necessary to advance sustainable development across the globe. Nevertheless, the multilateral approach to global policy making is currently facing significant challenges. Pressures have materialized in several areas, including international trade, international development finance and tackling climate change. These threats to multilateralism come at a time when international cooperation and governance are more important than ever, as many of the challenges laid out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are global by nature and require collective and cooperative action. Waning support for multilateralism also raises questions around the capacity for collaborative policy action in the event of a sharp global economic downturn.

A withdrawal from multilateralism would pose further setbacks for those already being left behind. The multilateral system is facing challenges in part because the gains from globalization and other processes have not been equally shared and the needs

of many people have not been met. The solution is not to withdraw into nationalism and unilateral action, but instead to address the weaknesses of the current system and strengthen the multilateral framework.

Follow Us