World Economic Situation and Prospects: February 2024 Briefing, No. 178

Global outlook 2024: Tight monetary policy and geopolitical uncertainty weigh on growth

Global outlook 2024: Tight monetary policy and geopolitical uncertainty weigh on growth

Resilience of global growth in 2023 masks underlying risks and vulnerabilities

The world economy proved remarkably resilient in 2023 despite sharp monetary tightening, escalation of geopolitical conflicts and heightened economic uncertainty. In several large developed and developing countries, economic growth exceeded expectations, with strong labour markets supporting consumer spending. At the same time, global inflation declined significantly on the back of lower energy and food prices, allowing central banks to slow or pause interest rate hikes. This veneer of resilience, however, masks both short-term risks and structural vulnerabilities. Underlying price pressures are still elevated in many countries. A further escalation of conflicts in the Middle East poses the risk of disrupting energy markets and renewing inflationary pressures worldwide. As the global economy braces for the lagged effect of sharp interest rate increases, the major developed country central banks have signalled their intention to keep policy rates higher for longer. The prospects of a prolonged period of elevated borrowing costs and tight credit conditions present strong headwinds for a world economy that is saddled with high levels of debt, while in need of increased investment, not only to revive growth but also to fight climate change and accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Moreover, tight financial conditions, coupled with a growing risk of geopolitical fragmentation, are weighing on global trade and industrial production.

Against this backdrop, global GDP growth is projected to slow from an estimated 2.7 per cent in 2023 to 2.4 per cent in 2024 (figure 1). Growth is forecast to improve moderately to 2.7 per cent in 2025 but will remain below the average pre-pandemic (2011–19) growth rate of 3.0 per cent. While the world economy avoided a sharp downturn in 2023, a protracted period of subpar growth looms large. Growth prospects for many developing countries, especially vulnerable and low-income countries, remain subdued, making a full recovery of pandemic losses ever more elusive and threatening to further set back sustainable development.

Against this backdrop, global GDP growth is projected to slow from an estimated 2.7 per cent in 2023 to 2.4 per cent in 2024 (figure 1). Growth is forecast to improve moderately to 2.7 per cent in 2025 but will remain below the average pre-pandemic (2011–19) growth rate of 3.0 per cent. While the world economy avoided a sharp downturn in 2023, a protracted period of subpar growth looms large. Growth prospects for many developing countries, especially vulnerable and low-income countries, remain subdued, making a full recovery of pandemic losses ever more elusive and threatening to further set back sustainable development.

Growth in developed economies is projected to slow in 2024

The economy of the United States of America defied expectations in 2023, growing at a robust rate of 2.5 per cent. Consumer spending remained strong backed by continued job growth, higher real wages and rising asset prices. But the Federal Reserve’s past rate hikes are expected to dampen consumption and investment in 2024, with annual GDP growth projected to slow to 1.4 per cent. Among the other developed economies, growth prospects for Europe and Japan remain subdued. In the European Union, GDP is projected to expand by 1.2 per cent in 2024, following growth of only 0.5 per cent in 2023. The mild recovery is expected to be supported by a gradual pick-up in consumer spending as inflationary pressures ease, real wages rise, and labour markets remain robust. In Japan, GDP growth is forecast to slow from 1.7 per cent in 2023 to 1.2 per cent in 2024 despite continued accommodative monetary and fiscal policy stances. Softening growth in China and the United States – the country’s main trading partners – is expected to curb net exports this year.

In the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Georgia, economic growth in 2023 was stronger than previously expected, reflecting resilience of the Russian Federation’s economy, a moderate recovery in Ukraine, and strong performance in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Regional GDP growth is projected to moderate from 3.3 per cent in 2023 to 2.3 per cent in 2024, with higher inflation and the resumption of monetary tightening in the Russian Federation weighing on domestic demand.

Tight financial conditions dampen growth prospects in many developing countries

Tight financial conditions dampen growth prospects in many developing countries

Short-term growth prospects for developing countries and regions vary significantly (figure 2). In China, annual growth reached 5.2 per cent in 2023 amid recovery from COVID-19-related lockdowns. Weakness in the property sector and soft external demand are expected to nudge growth down moderately to 4.7 per cent in 2024. Average growth in East Asia is projected to decline from 4.9 per cent in 2023 to 4.6 per cent in 2024. Private consumption growth is expected to remain firm, supported by easing inflationary pressures and steady labour market recovery. While the recovery of services exports – particularly tourism – has been robust, weak global demand will likely depress merchandise exports. In South Asia, GDP expanded by an estimated 5.3 per cent in 2023 and is forecast to grow by 5.2 per cent in 2024. India, which remains the world’s fastest-growing large economy is projected to see GDP increase by 6.2 per cent in 2024, following 6.3 per cent growth in 2023, amid robust domestic demand and strong manufacturing and service sectors. Tight financial conditions, fiscal and external imbalances and the return of the El Niño climate phenomenon cast a shadow over the outlook for several other South Asian economies.

While East Asia and South Asia enjoy solid growth prospects for 2024, Africa, Western Asia and Latin America face a more challenging outlook. Economic growth in Africa is projected to remain modest, edging up from an estimated 3.3 per cent in 2023 to 3.5 per cent in 2024 as the region is buffeted by the global economic slowdown and tighter monetary and fiscal conditions. Debt sustainability risks will continue to undermine growth prospects in many countries. The impacts of the climate crisis are a growing challenge for key sectors such as agriculture and tourism. Geopolitical instability continues to adversely impact several subregions, notably the Sahel and North Africa. In Western Asia, GDP growth is forecast to accelerate from an estimated 1.7 per cent in 2023 to 2.9 per cent in 2024 amid a recovery in Saudi Arabia and robust expansion of non-oil sectors. In Türkiye, the authorities aggressively tightened monetary policy to combat inflation, dampening growth prospects for 2024. The outlook for Latin America and the Caribbean remains challenging, with GDP growth projected to slow from 2.2 per cent in 2023 to 1.6 per cent in 2024. While inflation has been easing, it remains elevated, and structural and macroeconomic policy challenges persist. In 2024, tight financial conditions will undermine domestic demand, and slower growth in China and the United States will constrain exports.

Vulnerable country groups are facing moderate growth prospects

The least developed countries (LDCs) are projected to grow by 5.0 per cent in 2024, up from 4.4 per cent in 2023 but still well below the 7.0 per cent SDG growth target. Investment in LDCs will remain subdued amid volatile commodity prices. External debt service is estimated to have increased from $46 billion in 2021 to approximately $60 billion in 2023 (about 4 per cent of GDP), further squeezing fiscal space and constraining the ability of Governments to stimulate growth. Many small island developing States (SIDS) benefited from a rebound in tourism inflows in 2023, and the outlook for 2024 is generally positive. On average, SIDS are projected to grow by 3.1 per cent in 2024, up from 2.3 per cent in 2023. However, economic prospects of the SIDS remain vulnerable to the increasing impacts of climate change and to fluctuations in oil prices, which directly affect tourism flows and consumer prices. Economic growth in the landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) is projected to accelerate from 4.4 per cent in 2023 to 4.7 per cent in 2024. Several economies are benefiting from stronger investment, including foreign direct investment, especially in infrastructure.

Global labour market recovery remains uneven

The rebound in the global labour market since the pandemic has been swifter than the labour market’s recovery from the global financial crisis of 2008/09. By 2023, unemployment rates in many developed economies had fallen below pre-pandemic levels, reaching near-historic lows in the United States and several European economies. However, the labour market recovery was uneven, with developing economies in particular experiencing divergent trends. Brazil, China and Türkiye, for example, saw declining unemployment rates in 2023, but many other countries, especially in Western Asia and Africa, continue to struggle with high unemployment and low levels of formal employment. In many economies, nominal wage growth failed to keep pace with inflation, exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis. Labour market conditions across developed and developing countries will likely weaken in 2024, with the lagged effect of monetary tightening taking a toll on employment.

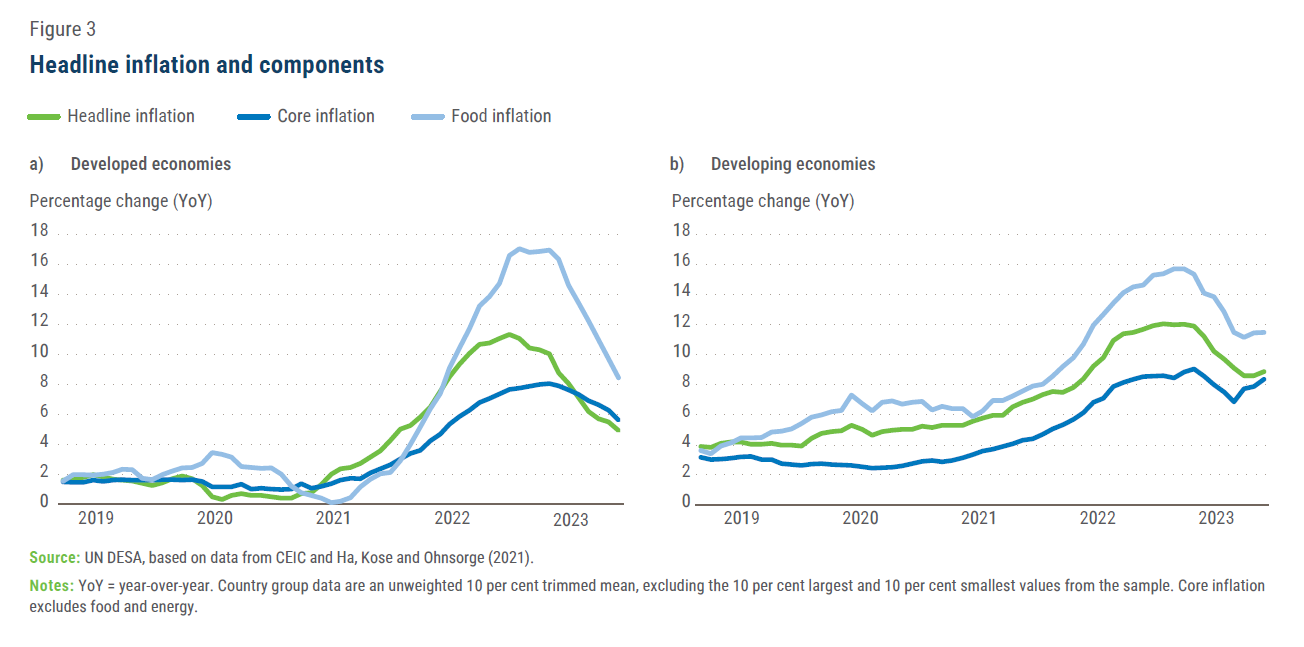

Global inflation is easing, but food insecurity continues to rise

After surging for two years, global inflation declined in 2023 but remained well above the 2010–2019 average (figure 3). Global headline inflation fell from 8.1 per cent in 2022, the highest value in three decades, to an estimated 5.7 per cent in 2023. A further decline to 3.9 per cent is projected for 2024 due to further moderation in international food prices and weakening demand. In developed economies, headline inflation has fallen sharply, whereas core inflation has remained more persistent amid rising service sector prices and tight labour markets. In almost a quarter of all developing countries – home to about 300 million people living in extreme poverty – annual inflation is forecast to exceed 10 per cent in 2023, further eroding the purchasing power of households and undermining poverty reduction efforts.

Local food prices have remained high, particularly in Africa, South Asia and Western Asia, due to limited pass-through from international to local prices, weak domestic currencies, and climate-related shocks. High food prices are disproportionately affecting the poorest households, which spend a larger share of their income on food. In 2023, an estimated 238 million people experienced acute food insecurity, an increase of 21.6 million people from the previous year, with women and children being particularly vulnerable. In the absence of significant progress, nearly one in four women and girls is projected to be moderately or severely food insecure by 2030.

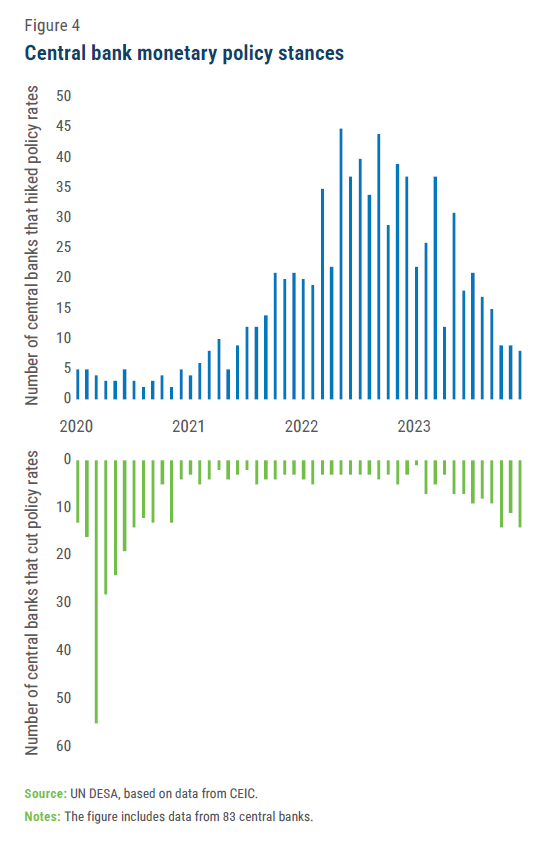

Monetary policy stances are increasingly diverging

With headline inflation easing, monetary policy stances across the world began to diverge. While many central banks continued to hike interest rates in 2023, others initiated a monetary easing cycle (figure 4). The global monetary policy stance, however, remains largely restrictive. The Federal Reserve and other developed country central banks are likely to keep interest rates higher for longer given upside risks to inflation from rising nominal wage growth and escalating geopolitical tensions. In addition to hiking policy rates, the major developed country central banks (except for the Bank of Japan) have continued to reduce the assets on their balance sheets, a monetary policy measure known as quantitative tightening (QT), to remove excess liquidity. The implementation of QT has raised significant financial and fiscal stability concerns. Although QT has contributed to tighter financial conditions, the impact on long-term bond yields has been limited due to the predictable and gradual pace of QT implemented by the central banks.

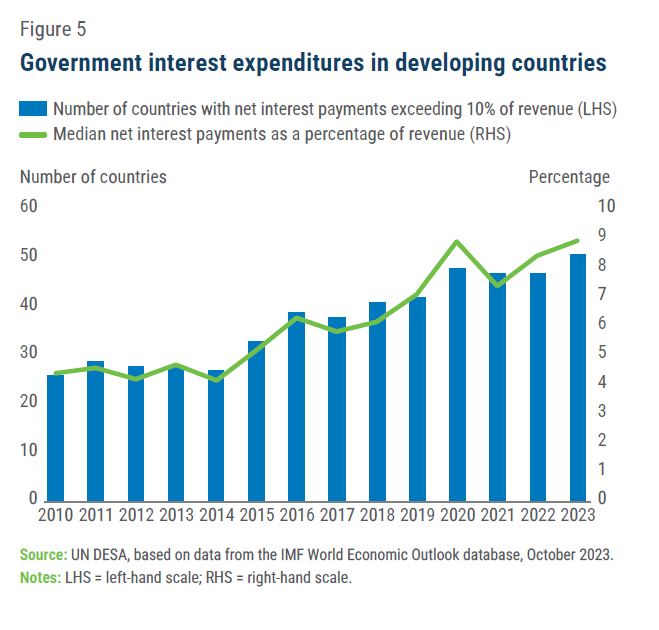

Monetary tightening in major developed countries continues to have significant spillover effects on developing countries. Although international financial conditions generally remained benign in 2023, high borrowing costs, constrained access to international capital markets, and weaker exchange rates have exacerbated debt sustainability risks in many developing countries. During the post-pandemic period, fiscal revenue stagnated or even fell, while the debt-servicing burden continued to increase, especially in developing countries with high levels of dollar-denominated debt (figure 5). This is particularly concerning at a time when developing economies need additional external financing to stimulate investment and growth, address climate risks, and accelerate progress towards the SDGs. The LDCs have experienced a decline in official development assistance (ODA), further aggravating the financing squeeze.

Global investment growth is projected to remain subdued

Global investment growth is projected to remain subdued

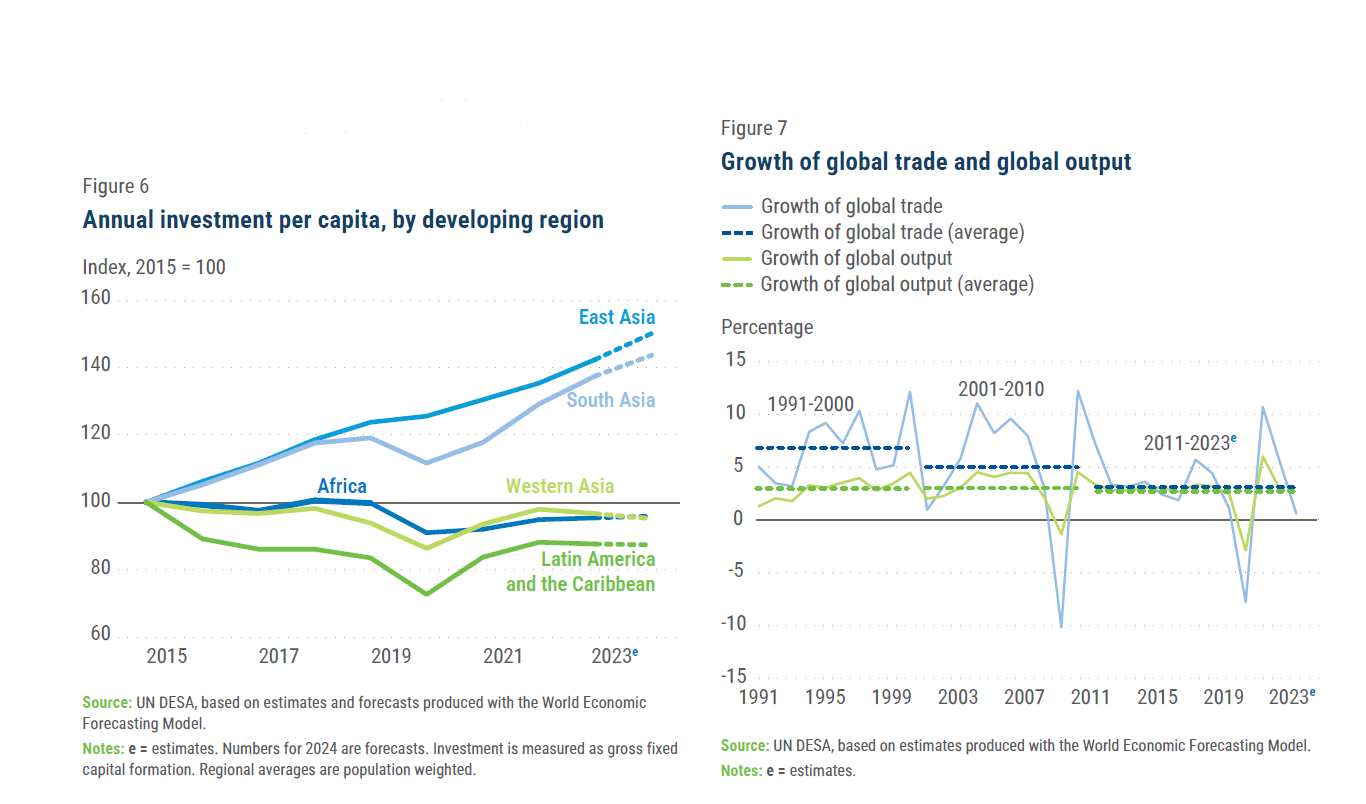

Gross fixed capital formation grew by an estimated 1.9 per cent in 2023, down from 3.3 per cent in 2022 and far below the average pre-pandemic growth rate of 4.0 per cent. In both developed and developing economies, investment growth had been slowing even before the pandemic. Ultra-loose monetary policy adopted in the aftermath of the global financial crisis was not associated with a strong upturn in investment. The current environment of high borrowing costs and elevated political and economic uncertainties will further weigh on investment growth. Among the developing regions, Africa, Western Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean continue to struggle with high financing costs and other challenges that hinder investment (figure 6).

International trade is losing steam as a driver of growth

Growth in global trade was very weak in 2023. International trade in goods and services is estimated to have increased by only 0.6 per cent, far below the 5.7 per cent growth rate recorded in 2022. Global trade growth is expected to recover to 2.4 per cent in 2024 but will likely remain well below the pre-pandemic trend of 3.2 per cent. The weakness in global trade is attributable to a slump in merchandise trade amid a shift in consumer spending from goods to services, monetary tightening, a strong dollar and geopolitical tensions. Trade in services, particularly tourism and transport, continued to recover in 2023. Overall, international trade has lost some of its dynamism since the global financial crisis of 2008. Not only has trade growth slowed considerably, but the ratio of average trade growth to average GDP growth has also declined (figure 7). In part, this reflects an increasing share of non-tradable goods and services in total output. The current trends are expected to persist in the coming years, with trade growth projected to remain subdued and export-led growth strategies giving way to domestic-demand-driven growth strategies.

Central banks face a delicate balancing act

Central banks worldwide are expected to continue facing difficult trade-offs in 2024 as they strive to manage inflation, revive growth, and ensure financial stability. Policy uncertainties loom large as the full impact of monetary tightening is yet to materialize. Central banks in developing economies face the additional challenge of growing balance-of-payments pressures and debt sustainability risks and thus need to use a broad range of tools – including capital flow management, macroprudential policies, and exchange rate management – to minimize the adverse spillover effects of monetary tightening. Developing countries also need to strengthen their technical and institutional capacities, focusing on timely economic and financial data collection and strengthened supervisory capabilities. Early warning indicators and country risk models can help monetary authorities spot domestic and external risks and vulnerabilities.

While a growing number of central banks are expected to shift towards monetary easing to support aggregate demand in 2024, the impact will, to some extent, depend on the actions taken by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. Central banks should strengthen international monetary policy cooperation or coordination and further improve communication to limit negative cross-border spillover effects.

Fiscal space is shrinking amid higher interest rates and tighter liquidity

Sharp increases in interest rates since the first quarter of 2022 and tighter liquidity conditions have adversely affected fiscal balances, renewing concerns about fiscal deficits and debt sustainability. For many developing countries, the lack of fiscal space restricts the capacity to invest in sustainable development and respond to new shocks. In 2022, more than 50 developing economies spent more than 10 per cent of total government revenues on interest payments, and 25 countries spent more than 20 per cent. Subdued medium-term growth prospects, together with the need for increased investment in education, health and infrastructure, will put further pressure on government budgets and exacerbate fiscal vulnerabilities. In developing countries with less vulnerable fiscal positions, Governments need to avoid self-defeating fiscal consolidation policies. Many of these economies need to bolster fiscal revenues to expand their fiscal space.

The increased use of digital technologies can help developing countries reduce tax avoidance and evasion. In the medium term, Governments will need to increase revenues through more progressive income, wealth and green taxes. Many economies must also improve the efficiency of fiscal spending and the effectiveness of subsidies and better target social protection programmes. Low-income countries and middle-income countries with vulnerable fiscal situations will need debt relief and restructuring to avoid devastating debt crises and protracted cycles of weak investment, slow growth, and high debt-servicing burdens.

Industrial policy is being deployed for sustainable development

Industrial policy, increasingly seen as crucial for fostering structural changes and supporting a green transition, is being revived and transformed. This shift is aimed at fixing market failures and aligning innovation with broader development goals. Innovation policies are also changing, with more ambitious, systemic and strategic approaches being employed. The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions have underscored the importance of domestic resilience, prompting major economies such as China, the United States and the European Union to invest heavily in the high-tech and green energy sectors. Most developing economies, however, struggle to fund industrial and innovation policies because of a lack of fiscal space and structural difficulties. A growing technological divide could further hinder the ability of developing countries to strengthen their productive capacities and move closer to realizing the SDGs.

Multilateralism is critical for progress towards SDGs

At the midpoint of the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the world remains vulnerable to disruptive shocks, including a rapidly unfolding climate crisis and escalating conflicts. The urgency and imperative of achieving sustainable development underscore that strong global cooperation is needed now more than ever. On the macroeconomic front, critical priorities for the international community include reinvigorating the multilateral trading system; reforming development finance and the global financial architecture and addressing the debt sustainability challenges of low- and middle-income countries; and massively scaling up climate financing.

The protracted slowdown in global trade – which in part reflects increased scepticism about the benefits of globalization – points to the need for reform of the multilateral trading system. Maintaining a rules-based, inclusive and transparent trading system is critical to boosting global trade and supporting sustainable development, including the energy transition. Urgent reforms are needed to ensure that the World Trade Organization (WTO) can resolve disagreements among member countries, accelerate progress on global trade agreements, and tackle new challenges, including the growing use of trade restrictions.

Global progress in financing sustainable development remains slow and fragmented. With many developing countries in debt distress, urgent and more effective international cooperation and support is needed to restructure debt and address refinancing challenges. The Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable, established in February 2023, aims to facilitate collaboration between stakeholders and enable coordination, information-sharing and transparency. Efforts are under way to improve contractual clauses to prevent and more effectively resolve debt distress and crises. There is a need for more robust and effective multilateral initiatives that provide clarity regarding steps and timelines for processes, the provision of debt standstills during negotiations, and better ways to ensure adherence to the “comparability of treatment” principle among different creditors.

Scaling up climate finance is crucial to combat the climate crisis. According to recent estimates, $150 trillion in investment will be needed by 2050 for energy transition technologies and infrastructure, with $5.3 trillion required annually to transform the global energy sector alone. However, climate finance remains far below the level required to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as set out in the Paris Agreement in 2015. The effective operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund, formally adopted at the twenty-eighth Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28), and the scaling up of financing commitments made in connection with this Fund will be critical for helping vulnerable countries cope with the impacts of climate disasters. Reducing fossil fuel subsidies, strengthening the role of multilateral development banks in climate finance, and promoting technology transfer to developing countries are vital for strengthening climate action worldwide.

Follow Us