World Economic Situation and Prospects: April 2025 Briefing, No. 189

Navigating through an inflationary world

Navigating through an inflationary world

The current inflation landscape

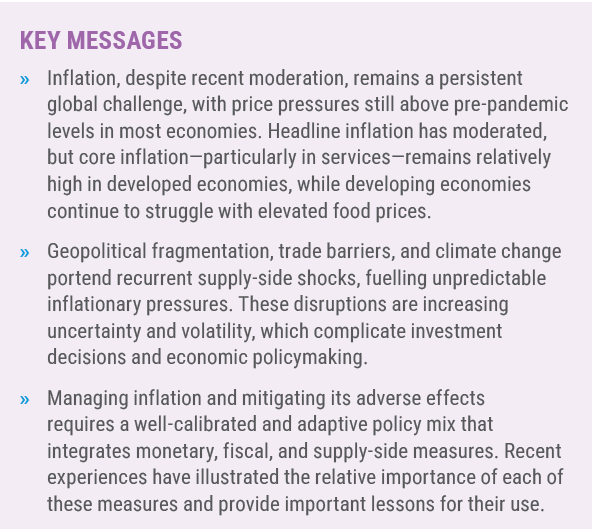

Inflation has once again become a central topic among academics, policymakers, and in the daily lives of citizens. For much of the past two decades, inflation remained relatively low and stable in most developed and developing economies, even as a few countries experienced high inflation amid economic and financial crises or macroeconomic mismanagement. Between 2000 and 2020, global inflation averaged 3.4 per cent, compared to 8.0 per cent in the 1980s and 7.1 per cent in the 1990s. Even in developing countries, where inflation is typically higher and more volatile, it followed a downward trend since the mid-1990s, supported by technology-driven efficiency gains and stronger macroeconomic policy frameworks, including inflation-targeting regimes (Duncan and others, 2024). In recent years, however, global inflation surged (figure 1), driven by COVID-19-induced supply chain disruptions, strong post-pandemic demand, and sharp increases in international commodity prices, further exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. This fuelled a cost-of-living crisis, as soaring prices for essentials eroded household purchasing power, particularly for lower-income families, deepening poverty and further widening socioeconomic inequalities.

Despite recent moderation, with global headline inflation falling from 5.6 per cent in 2023 to 4.0 per cent in 2024, price pressures remain a persistent challenge for policymakers worldwide. By early 2025, annual headline inflation still exceeded its 2015–2019 average in 89 out of 134 countries—around 65 per cent—underscoring ongoing difficulties in curbing price pressures. In most developed economies, inflation remains above central bank targets, though underlying drivers vary across countries. In the United States, persistent core inflation has been driven largely by robust consumer demand, a tight labour market, and rising services prices—particularly in housing. In the euro area, persistent upward pressure on services prices reflects strong wage growth, along with robust consumer spending on leisure activities in the tourism, hospitality and recreational services sectors.

At the same time, heightened policy uncertainty and rising trade barriers contribute to renewed inflationary pressures. The recent U.S. tariff package—which includes a 10 per cent baseline tariff on all imports and significantly higher rates for China—risks increasing import costs for both final and intermediate goods, while disrupting global trade flows. In response, retaliatory measures—such as China’s announcement of additional tariffs on all U.S. goods—are set to further escalate trade tensions. These developments could generate inflationary spillovers across the world through higher input costs, reduced supply-chain efficiencies, and increased market uncertainty.

These dynamics may not only raise price levels for specific goods in the short-term but could also contribute to broader inflationary pressures as well as greater volatility and uncertainty. A key concern in this context is the role of inflation expectations. Inflation expectations influence wage-setting, pricing behaviour, and central bank credibility, making them a crucial channel in the transmission and persistence of inflation. Amid the recent surge in policy uncertainty in the United States, the University of Michigan reported a sharp rise in inflation expectations in March 2025, with one-year expectations surging to 4.9 per cent (figure 2) and five-year expectations reaching 3.9 per cent—a three-decade high. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, average one-year inflation expectations rose to 3.4 per cent in February, while five-year expectations increased to 3.6 per cent (Bank of England, 2025). Amid headwinds to growth and heightened policy uncertainty, developed country central banks face increasingly difficult trade-offs between controlling inflation—and anchoring inflation expectations—and supporting economic activity.

Inflation remains elevated in many developing economies as well, with more than 20 countries still experiencing double-digit inflation by early 2025. In Africa and Western Asia, for example, price pressures are well above long-term averages (United Nations, 2025). While headline inflation is expected to decline further in 2025, high and volatile food inflation remains a major concern in many developing countries, averaging above 6 per cent. This persistence is driven by limited transmission of the decline in international prices, currency depreciation, and climate-related disruptions to agricultural output. In Brazil, for example, food price inflation surged from 1.8 per cent in January 2024 to over 7.0 per cent by January 2025. Between 2018 and late 2024, the number of countries experiencing annual food inflation above 20 per cent has tripled, rising from six to eighteen.

The recent inflation episode: drivers and evolution

In the last five years, global shocks have shaped inflation dynamics across both developed and developing countries. However, the importance of specific drivers and impacts varied, reflecting differences in economic structures, vulnerabilities to external shocks and policy responses. In developed economies, headline inflation surged from less than 1 per cent in early 2021 to over 11 per cent by the end of 2022, primarily due to rising oil, gas, and food prices following the war in Ukraine. Supply chain disruptions played a significant role in triggering price pressures, particularly in durable goods and automobiles, where semiconductor shortages and shipping delays created massive supply bottlenecks. Core inflation also rose substantially, albeit more gradually than headline inflation, reflecting the partial pass-through of energy and food price hikes. Later, in 2023, tight labour markets and wage growth, coupled with strong consumer demand, also contributed to upward pressures on prices. A key driver of these pressures was the acceleration in services inflation, particularly in housing, financial services, insurance, and medical care.

Developing economies also experienced a sharp rise in inflation, due to their higher dependence on imported energy and fuel, currency depreciation, and structural vulnerabilities. The impact of surging food and energy prices on headline inflation was particularly pronounced, as these essentials constitute a larger share of household consumption. For instance, in low-income countries in Africa and South Asia, food expenditures account for over 40 per cent of total consumer spending, compared to just 10–15 per cent in most European Union economies (USDA ERS, 2023). Average headline inflation in developing countries increased from 4.6 per cent in early 2021 to more than 11 per cent in November 2022, with several economies facing inflation rates above 25 per cent.

A key amplifying factor in developing economies was currency depreciation, as many countries saw their domestic currencies weaken against the U.S. dollar throughout 2022. This raised the cost of imports, particularly food and fuel, thereby intensifying domestic inflationary pressures. Currency depreciation was largely driven by the U.S. Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening in response to stubborn domestic inflation. While countries such as Argentina, Nigeria and Türkiye experienced depreciation due to country-specific factors, a broader wave of currency weakening affected many developing economies. In Egypt, repeated currency devaluations, combined with a heavy reliance on food imports—particularly wheat—also intensified inflationary pressures. Unlike in developed economies, wage-driven price pressures were much less prevalent due to a smaller post-pandemic monetary and fiscal stimulus, larger informal labour markets, and higher levels of underemployment.

Furthermore, there is some evidence indicating that firms’ responses to rising costs and supply shocks exacerbated inflationary pressures. Companies with substantial market power not only passed on higher costs but also expanded profit margins (Lagarde, 2023). Empirical evidence, particularly in developed economies, indicates that profit expansion was prevalent, further propagating price pressures (Bivens and Banerjee, 2023; Uxó and others, 2023; Matamoros, 2023). Arce and others (2023), for example, estimate that unit profits contributed around two-thirds to inflation in the euro area in 2022, whereas in the previous 20 years their average contribution had been around one-third. Similarly, Hansen and others (2023), find that rising corporate profits explained nearly half of Europe’s inflation increase between mid-2021 and mid-2023, as firms raised prices beyond the surge in imported energy costs. Firms may have been able to raise prices beyond their costs due to temporary monopolies in industries facing capacity constraints and consumers’ expectations of rising prices.

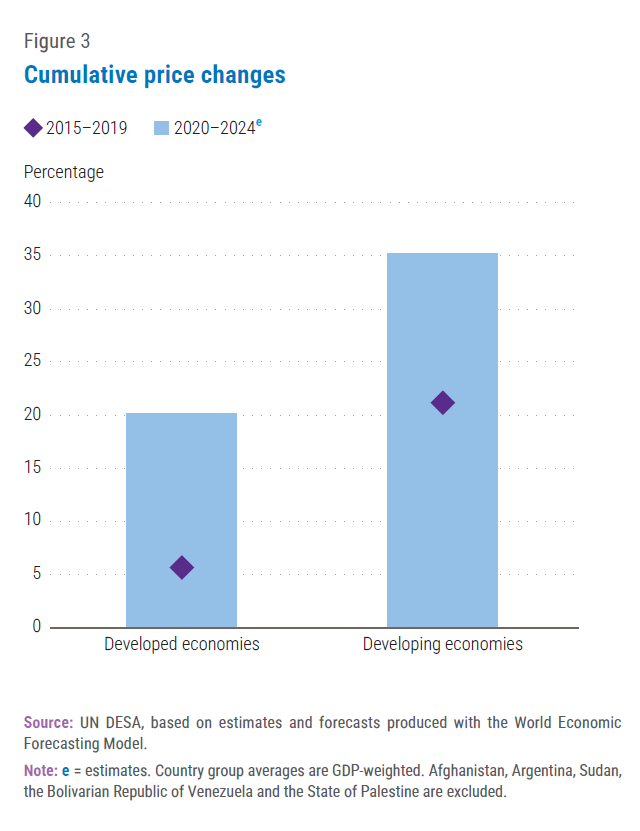

Even as inflation has been a global phenomenon, its impacts have been uneven across countries, sectors, households, and firms. These disparities reflect underlying differences in consumption patterns, income levels, market structures, and the nature and timing of policy responses—underscoring the often regressive and asymmetric nature of inflation impacts. At the aggregate level, between 2020 and 2024, consumer prices rose cumulatively by about 20 per cent in developed economies and 35 per cent in developing economies—substantially exceeding the increases recorded during the previous five-year period (figure 3). As wages, in general, failed to keep pace with price increases, households’ purchasing power was eroded, requiring them to change consumption patterns in order to stay within their (fixed) budgets. Such adjustments could have disproportionately affected poorer households, exacerbating socioeconomic inequalities. This disparity stems primarily from differences in consumption patterns: essential goods and services—food, energy, and rent, which account for a larger share of spending among lower-income households—recorded some of the steepest price increases.

Even as inflation has been a global phenomenon, its impacts have been uneven across countries, sectors, households, and firms. These disparities reflect underlying differences in consumption patterns, income levels, market structures, and the nature and timing of policy responses—underscoring the often regressive and asymmetric nature of inflation impacts. At the aggregate level, between 2020 and 2024, consumer prices rose cumulatively by about 20 per cent in developed economies and 35 per cent in developing economies—substantially exceeding the increases recorded during the previous five-year period (figure 3). As wages, in general, failed to keep pace with price increases, households’ purchasing power was eroded, requiring them to change consumption patterns in order to stay within their (fixed) budgets. Such adjustments could have disproportionately affected poorer households, exacerbating socioeconomic inequalities. This disparity stems primarily from differences in consumption patterns: essential goods and services—food, energy, and rent, which account for a larger share of spending among lower-income households—recorded some of the steepest price increases.

Inflation outlook: risks and uncertainties moving forward

In the coming years, a number of factors indicate that supply-side shocks could recur, keeping inflationary pressures elevated. Rising economic fragmentation and the increasing trade restrictions elevate production costs, disrupt supply chains, and reduce efficiencies. When countries impose tariffs or trade barriers, import costs rise, driving up prices for consumers and businesses reliant on foreign inputs, with increases in prices of intermediate goods or raw materials having the potential to cascade through multiple final goods in the economy. For example, Cavallo and others (2021) investigate the introduction of United States’ tariffs ranging from 10 to 50 per cent on certain goods in 2018, and the retaliatory measures from Canada, China, the European Union, and Mexico. Tariffs passed through almost fully to United States import prices, with much lower rates of pass-through from exchange rate shocks into import prices. In a study for a large group of countries over several decades, Furceri and others (2021) shows that tariffs led to an increase in inflation after two years, in addition to lower output growth, higher unemployment and small effects on the trade balance.

Other factors are also important. Geopolitical fragmentation heightens global policy uncertainty, which can add inflationary pressures by discouraging long-term investment, disrupting production strategies, and increasing risk premiums. These risk premiums are often associated with higher price volatility, particularly in commodities and traded goods. Over time, such instability can also contribute to broader price volatility complicating economic decision-making. An increasing incidence of supply side shocks can also arise from climate change and associated extreme weather events, albeit not all of them are necessarily inflationary. However, as unexpected price increases become more frequent, inflationary expectations can rise beyond the limits designated by central banks, raising the spectre of self-fulfilling inflation in the economy.

Given the persistent inflationary challenges and the complex interplay of supply and demand forces, policymakers have turned to a mix of monetary, fiscal, and supply-side interventions to manage price pressures.

Responding to inflation: learning from recent experiences

Demand and supply considerations for policy choices

The recent surge in inflation sparked an examination of underlying causes, transmission mechanisms and emerging policy challenges. This debate largely centres on two perspectives (Martins, 2024). One attributes inflation primarily to excessive aggregate demand (Bergholt and others, 2024), emphasizing the role of expansive fiscal and monetary policies in the pandemic recovery. The other highlights structural and sectoral factors, arguing that inflation was mainly driven by supply-side constraints, global production bottlenecks, and the ability of dominant firms to raise prices in response to shifting market conditions (Weber and others, 2024). Importantly, these perspectives are not mutually exclusive, as both demand and supply-side forces interacted throughout the episode—supply-side constraints dominated the early stages, while demand pressures became more prominent later, particularly in developed economies such as the United States. These differing views naturally lead to distinct policy recommendations, with one favouring tighter monetary and fiscal policy and the other advocating targeted supply-side interventions.

Demand-side measures

Amid mounting inflationary pressures, central banks worldwide responded swiftly. The 2021–2023 monetary tightening cycle was among the most rapid, intense, and synchronized episodes of policy tightening. The U.S. Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and European Central Bank executed some of their fastest rate hikes, with the Fed raising rates by 525 basis points in 16 months—its most aggressive tightening since the 1980s. Initially considering inflation as transitory, major central banks later shifted to aggressive hikes to curb demand and ensure that expectations remained anchored around their respective inflationary target. In developing economies, many central banks acted early and decisively. Among a sample of 50 developing country central banks, 43 raised interest rates in 2022. By 2023, inflation began to ease as food and energy prices moderated and labour market pressures in developed economies subsided. As concerns over the growth prospects and financial stability grew, central banks slowed hikes and eventually began cutting rates.

Fiscal and supply-side measures

Amid significant supply-side disruptions that stoke inflation, the debate on policy responses continues to evolve. Conventional monetary policy tools—particularly interest rate hikes aimed at curbing aggregate demand and anchoring inflation expectations—may prove insufficient or even suboptimal when supply-side factors dominate. In such cases, they can impose significant economic costs, including slower growth, higher unemployment, and financial instability, but with limited impact on the root causes of inflation. Recognizing these limitations, between 2021 and 2023 many governments complemented monetary tightening with relatively novel fiscal and supply-side measures to mitigate the broader fallout—particularly the escalating cost-of-living crisis affecting households and vulnerable populations. Fiscal measures refer to government interventions through taxation, public spending, and transfers to protect vulnerable groups, while supply-side and administrative policies aim to ease production constraints, stabilize key markets, or directly influence prices. Depending on their design and financing, however, some of these interventions—particularly broad subsidies or untargeted tax cuts—can create additional inflationary pressures.

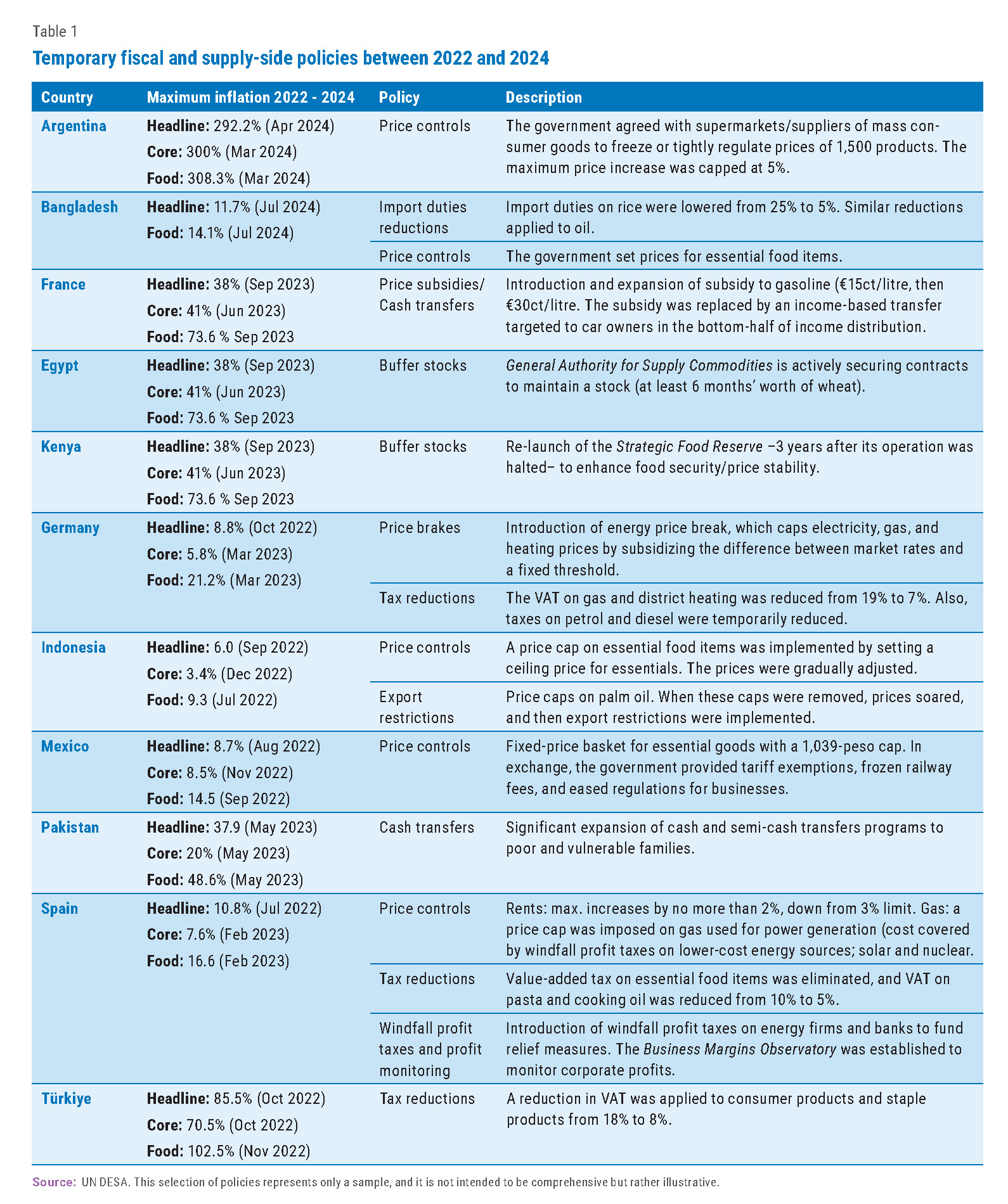

The fiscal measures comprised temporary value-added tax (VAT) reductions, targeted subsidies for energy and food, price stabilization mechanisms and export restrictions (Table 1). Amaglobeli and others (2023) report that cash and semi-cash transfers, VAT reductions and price subsidies were the most common measures across developed and developing countries, while reduction of customs duties or price freezes were also prevalent. Additionally, some governments established or reinforced medium-term strategies to address structural factors driving inflation, such as expanding buffer stocks, strengthening competition policies, or promoting domestic energy production. Amid greater fiscal policy space—reflected in stronger pre-pandemic fiscal positions, greater access to low-cost borrowing and more resilient fiscal revenues—developed economies were able to implement broader and more sustained fiscal and supply-side interventions, despite the significant financial burden. In contrast, limited access to financing and reduced revenues during the pandemic crisis forced many developing economies to rely on more limited measures.

A common fiscal policy response was the adoption of temporary VAT reductions, unprecedented in both scale and prevalence. By directly lowering the tax component of consumer prices, these measures helped reduce headline inflation, particularly for essential goods and services. These tax cuts, implemented in Argentina, Türkiye, Viet Nam, and several European Union countries—including France, Germany, Spain, Poland and Portugal—came at a high fiscal cost due to their broad scope. A number of countries also adopted price subsidies to limit the pass-through of international price increases to domestic consumers, particularly for energy and food. France, for example, introduced a broad-based fuel price rebate that initially reduced gasoline prices by €0.15 per litre, later expanded to €0.30 per litre. The subsidy provided widespread relief and was almost fully passed through to consumers, yet it imposed a high fiscal burden and delivered disproportionate benefits to higher-income households.

Meanwhile, some countries resorted to strategic, targeted and temporary price stabilization mechanisms. By limiting price increases in a few essential goods and services, these measures can directly limit headline inflation and contain broader price pressures, particularly in moments of acute supply shocks. As argued by Weber and others (2024), such interventions can be especially effective in critical sectors—like food, fuel, and housing—where price surges not only affect basic living costs but also risk triggering broader inflationary dynamics and social instability.

Importantly, many of these recent price stabilization efforts differ from past experiences with widespread and prolonged price controls, which often led to supply shortages and severe market distortions (Guénette, 2020). In contrast, countries that achieved better outcomes—such as Mexico and Spain—implemented strategic, time-bound, and targeted measures, usually paired with other supply-side incentives and broader macroeconomic adjustments. Additionally, targeted coverage (focused on key essentials), coupled with decisive monetary policy actions, helped anchor inflation expectations. These design features were essential in allowing governments to temporarily cushion households without replicating the adverse consequences historically associated with generalized price controls.

Some countries turned to trade restrictions to combat inflation. By limiting exports or easing import barriers, these measures aim to increase domestic supply and reduce upward pressure on prices—particularly for food and energy—during periods of international market volatility. Indonesia, for example, imposed a domestic price cap on cooking oil to counter a 50 per cent surge in crude palm oil prices. However, enforcement challenges led to shortages, prompting the government to quickly remove the cap—causing prices to soar again. This led to strict export restrictions, prompting complaints from domestic producers—particularly small-scale farmers— and backlash from import-dependent countries, as Indonesia supplies 56 per cent of global exports.

Additionally, governments in some countries have been reinvesting in buffer stocks, reflecting a renewed interest in this policy tool amid persistently high food inflation in recent years (Manduna, 2024). Buffer stocks are publicly held reserves of essential commodities, such as staple foods, managed with the aim of stabilizing prices, ensuring availability during shocks, and mitigating inflationary pressures by smoothing supply fluctuations (Weber and Schulken, 2024).

The implementation of some of these fiscal and supply-side policy measures presents significant challenges and potential trade-offs. VAT reductions, for instance, can be costly, erode public revenues, and lead to asymmetric price adjustments when reversed. Moreover, broad-based subsidies, untargeted transfers and prolonged tax cuts can widen fiscal deficits, and stimulate demand, and reinforce inflationary pressures rather than mitigate them if sustained for too long. Price controls may provide temporary relief but risk distorting markets, discouraging investment, and fuelling shortages. Similarly, export restrictions can stabilize domestic prices but may undermine producer incentives, drive up global prices, and provoke retaliatory trade actions. As a result, these fiscal and supply-side interventions can generate inefficiencies, impact fiscal revenues and create international spillovers. Given these risks, ensuring that these interventions remain targeted, temporary, and data-driven is crucial to avoiding fiscal imbalances and unintended economic distortions. Also, clear exit strategies and robust monitoring mechanisms are crucial to prevent excessive fiscal burdens and misallocation of resources.

Towards a balanced and adaptive policy approach

Although several of the drivers of the post-pandemic inflationary surge appear to have abated, the inflation outlook remains complex, shaped by geopolitical fragmentation, trade restrictions, climate change and other pressures. Recent experiences have shown that even when supply-side shocks and disruptions are expected to be transient, they can trigger longer term inflationary episodes and price volatility. Navigating this evolving landscape demands thinking beyond conventional policy approaches and requires a flexible and adaptive policy mix that integrates monetary policy with targeted fiscal and supply-side measures.

In this context, central banks may need to reassess their monetary policy frameworks—including inflation targets and broader mandates—to ensure their increased effectiveness in an era of changing inflation dynamics. At the same time, fiscal policy must complement these efforts by ensuring that fiscal measures provide critical support to vulnerable populations. Given that supply constraints cannot be immediately altered by monetary or fiscal policy, well-designed longer-term strategies that strengthen production capacity and logistical efficiency are crucial to addressing structural supply chain bottlenecks. Enhancing supply resilience through targeted investments in infrastructure, energy, and food security can mitigate inflationary risks. As geopolitical uncertainties grow and climate-related disruptions intensify, strategic policymaking and institutional adaptability are essential to stabilizing inflation while fostering sustainable and inclusive growth.

Follow Us