18 July marks the Nelson Mandela International Day, designated in recognition of Mandela's dedication to the service of humanity, while acknowledging his contribution to the struggle for democracy internationally and the promotion of a culture of peace. The article below is published as an academic and personal reflection within the framework of this international observance, aiming to highlight parallelisms in the struggles made by Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi, and how Gandhian values influenced political developments in South Africa.

Our somewhat dystopian times are witnessing a debate everywhere about global challenges beyond national capacities. It is engaging national leaders, strategic thinkers, and the common man alike. Inadequacy of global response and of the mandated global institutions to the menacing, accelerating challenges, are resulting in profound questioning about statecraft and about managing political change itself. At individual and social levels, the debate reflects distrust of political elites and the slide towards an uneasy comfort in narrowing, splitting identities. In addition to this, newer technologies are empowering the individual but also raising complex ethical questions.

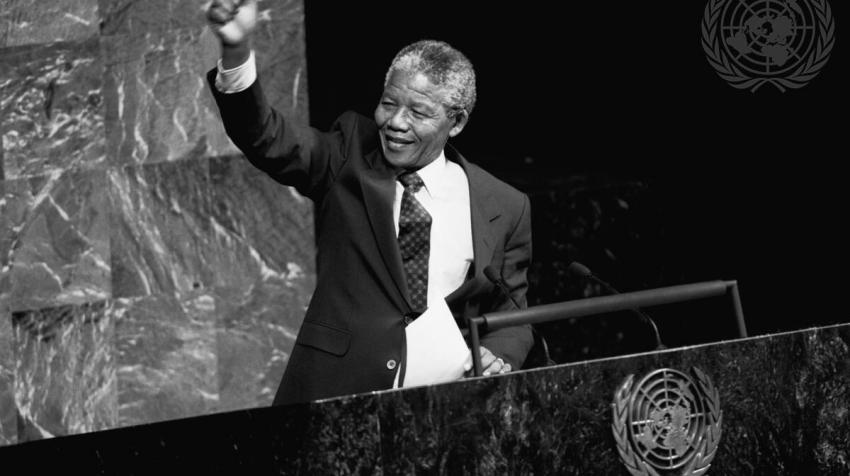

In these uncertain times, why does Nelson Mandela matter? Despite the bitter, fierce struggle of the South African black community against the oppressive, dehumanizing apartheid regime and his own decades-long personal suffering, he led his people to a modern country based on inter-racial concord and equity turning their backs on centuries of violence and bigotry. His healing touch, along with other leaders, ensured a smooth political transformation in one of Africa’s most important countries. And this transformation had continental and global ramifications. His prestige helped in critical international situations and in crystallizing the vision of a more peaceful and equitable post-cold war order.

Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi chose the path of social cohesiveness as the only way of achieving a smooth political transformation to ensure a stable political system. They were both conscious that domestic political stability is a precondition for socioeconomic progress besides enabling countries to play a helpful, stabilizing role in international affairs. Mandela's political movement had espoused non-violence and, as David Hardiman describes, it paid close attention to the techniques of the one founded by Gandhi, for non-violent mass militant mobilization for breaking apartheid laws, displaying personal sacrifice and suffering.

Mandela himself was also conscious of the value of nonviolence as the true foundation of a post-apartheid South Africa. He wrote in his autobiography, “animosity between Afrikaner and Englishman was still sharp 50 years after the Anglo-Boer war; what would race relations be like between black and white if we provoked a civil war?.” The objectives of both Mandela and Gandhi were to fashion a strong political force capable of effecting political transformation conducive for the people to develop their inherent talents. This is of particular relevance if we consider for instance, that half of the world’s poor would be living in politically fragile countries in less than 10 years.

State fragility and collapse results in mass migrations and safe havens for violent extremism and terrorism, apart from internal socioeconomic devastation and polarization, regional spillover and wider geopolitical distrust. Resulting institutional dysfunctionality negatively impacts the global initiatives in fighting common challenges and takes much international effort, to resurrect stable political institutions and grassroots capacities. Hence, we must revisit the ideas and philosophies of Gandhi and Mandela. For Gandhi, nonviolent means for political struggle were a matter of absolute faith. Though Mandela considered them as a matter of political tactics, as his leadership demonstrated, he was fully aware of their value.

Gandhi generated, in doctrinal and programmatic terms, a political force subversive of the colonial system but capable of steering a political transformation for a smooth power transition at independence obviating breakdown of the government mechanism. This transformation was uplifting and empowering for the most disadvantaged. Resilient institutions withstood future shocks, external and internal, laying the foundation for India’s later socioeconomic growth within a robust democratic framework. Gandhi pivoted the freedom struggle in a non-violent direction in the wake of the horrific Jallianwala Bagh massacre (1919).

His rejection of violence, as explained by Karuna Mantena, was based on its perpetrator’s presumption of infallibility which human beings are not capable of; a logic of escalation is built into it. Satyagraha (Gandhi’s “truth force”) is direct action for collective protest, which is context-dependent and is defined in terms of orientation, mechanism, and disposition; it is also non-coercive and conscious suffering for its practitioner. For him as a self-described ‘practical idealist’, there is fusion of means and ends – or, rather means are everything. Despite the violence and mass migrations accompanying the Indian independence, political consolidation of the infant state was rapid.

In the interim government before the general elections based on universal franchise, he got the Congress leaders to invite other political leaders to join government, including those opposed to him. The ultimate test for the Gandhian values of selfless public service was his nomination of Jawaharlal Nehru, as future Prime Minister of the country, over the claim of Vallabhbhai Patel who commanded overwhelming support. The mass base of the governing party ensured implementation of the program of rapid socioeconomic regeneration which was seen as a model by others. For Gandhi, nationalism was actually an essential prerequisite of internationalism, as countries needed to be self-sufficient to be equal and productive players in the international community.

Furthermore, his values shaped India’s foreign policy for years and decades. Today, decolonization and a fairer global order, bear the imprimatur of Gandhian thinking. Undoubtedly, Mandela became a torch bearer of these very same values for a global order we all strive for. A reflection on the political struggles of Mandela and Gandhi, now when we commemorate the birthday of the former South African leader, puts the current global challenges in different perspective. Steering political change, through the empowering and ennobling of the most disadvantaged, is key to resilient institutions. As we ponder the future of global affairs, their legacies need to be internalized by our leaders, the international institutions and the world as a whole.

This article was drafted by Yogendra Kumar, former Ambassador of India to the Philippines, Namibia and Tajikistan, and author of the book 'Geopolitics in the Era of Globalisation: Mapping an Alternative Global Future' (Routledge, 2021)