Drafting Resolutions

Drafting Resolutions

Background

There are six principal organs of the UN. However, since the Trusteeship Council suspended operation on 1 November 1994, only three adopt resolutions: the GA, the SC, and ECOSOC. This section will explore the nature of drafting resolutions that apply equally to all three organs.

If you consider that the Charter is the basic text, or “Constitution,” for the organization, you can also consider that resolutions adopted by the GA constitute the “law” of the Organization. And because it is the law of the Organization, it stands to reason that the text you produce should be clear. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes, resolutions adopted by the GA may be obscure or even seem to be contradictory. This is not necessarily the fault of the drafter. Contrary to what happened in the early days when every draft resolution was put to the vote, nowadays, every draft resolution is the result of informal consultations. In the process, compromises are made and the final language of the text sometimes may be unclear.

The main goal of a conference is to adopt an outcome document that Member States as a whole can agree on. Draft resolutions can be tabled as soon as the GA agenda is adopted and it has been decided whether a particular agenda item will be allocated to the GA Plenary or one of its Main Committees.

Member States consulting on a draft resolution or decision before its formal adoption may use one of two common practices.

Negotiations Before Tabling

The main sponsor consults with Member States and holds informal negotiations on the draft before tabling the “best version possible.” This allows for action to be taken immediately after the introduction of the L-document. This is the normal practice in the Plenary.

Negotiations After Tabling

The main sponsor tables a draft resolution or decision without prior consultations. After the introduction of the L-document, informal negotiations take place, led by either the main sponsor or by a facilitator appointed by the Chair of a Main Committee. If consensus is reached, the negotiated text will replace the original draft. This is done in two ways: either the sponsor withdraws the original L-document, and a new L-document is issued after a bureau member has tabled the negotiated text; or the sponsor submits the negotiated text as a revision of the original L-document (issued as L.xx/Rev.1). In both cases, the resolution/decision is adopted by consensus.

If the negotiations do not result in consensus, the sponsor can either request action on the original L-document or on the negotiated text (issued as L.xx/Rev.1). In both cases, the draft resolution/decision is submitted to a vote, often accompanied by proposals for amendments and requests for votes on specific paragraphs.

Drafting and negotiation are closely related because the negotiations often involve agreeing on the words that are used to describe an action that is to be taken on a particular agenda item.

Life History of Text

Texts that international conferences adopt begin as a draft of the words that will advance a particular aim (e.g., increased safety of shipping, measures to remedy a public health problem, etc.). Until they are adopted at the conference, these words are no more than proposals—and are often forgotten. Once adopted, they carry the authority of the conference.

Structure of Resolutions and Words Commonly Used

The most common form in which a conference expresses itself is by way of resolutions. Resolutions have a particular format.

Each resolution consists of one long single sentence. It begins with the name of the main organ that is adopting the resolution (e.g., the GA or the SC) and is followed by several preambular paragraphs. Preambular paragraphs are not really paragraphs, but clauses in the sentence. Each one starts with verb in the present participle (e.g., Recalling, Considering, Noting), which is capitalized, and ends with a comma. Sometimes the clause begins with more than one keyword, such as, Noting with satisfaction, Noting with regret, etc. These words are always italicized.

After the preambular paragraphs come the operative paragraphs, each of which begins with a verb in the present tense, also capitalized, and finishes with a semi-colon, except for the last, which has a period at the end of it.

Words Commonly Used at the Beginning of Preambular Paragraphs

- Acknowledging

- Affirming

- Appreciating

- Approving

- Aware

- Bearing in mind

- Believing

- Commending

- Concerned

- Conscious

- Considering

- Convinced

- Desiring

- Emphasizing

- Expecting

- Expressing

- Fully aware

- Guided by

- Having adopted

- Having considered

- Having noted

- Having reviewed

- Mindful

- Noting

- Noting with approval

- Noting with concern

- Noting with satisfaction

- Observing

- Realising

- Recalling

- Recognizing

- Seeking

- Taking into consideration

- Underlining

- Welcoming

- Whereas

Tips on Ordering Paragraphs in the Preambular Section

If the preamble is going to refer to the UN Charter, it should be put first. If the resolution starts with a general reference to the “purposes and principles in the Charter of the United Nations,” there should be another clause in the preamble that refers more specifically to a Chapter or Article within the UN Charter that elaborates the principles that are relevant to the subject of the resolution. The first time it is mentioned in the preambular or operative section it should be referred to as the Charter of the United Nations. After that, it can be referred to simply as the Charter.

References to past resolutions or decisions usually come second (e.g., “Recalling its resolution 65/309 of 19 July 2011). If the resolution was adopted in the SC, the correct wording would be “Recalling SC resolution 338 (1973) of 22 October 1973.” It is not considered good form to write, “Recalling resolution 338 (1973) of 22 October 1973 of the SC...” The first time a resolution of the SC is mentioned the date is included. After that, only the resolution number and year needs to be mentioned, for example, resolution 338 (1973).

Next, it is proper to include general observations about the content or purpose of the resolution that serves as the basis for the rest of the text. This helps set the stage for the call to action in the operative section of the resolution.

Finally, if a reference to a report on this item is to be included, it would go last (e.g., “Taking note of the report of the Secretary-General). If this is done, it is not considered proper to include the symbol of document in the text. This would go in a footnote.

Words Commonly Used at the Beginning of Operative Paragraphs

- Accepts

- Adopts

- Agrees

- Appeals

- Approves

- Authorizes

- Calls upon

- Commends

- Considers

- Decides

- Declares

- Determines

- Directs

- Emphasizes

- Encourages

- Endorses

- Expresses appreciation

- Expresses hope

- Invites

- Notes

- Notes with approval

- Notes with concern

- Notes with satisfaction

- Proclaims

- Reaffirms

- Recommends

- Reminds

- Repeals

- Requests

- Resolves

- Suggests

- Supports

- Takes note

- Urges

All resolutions have at least one operative paragraph, but many resolutions have several preambular and several operative paragraphs. If several preambular or operative paragraphs begin with the same word (for example, “noting” or “notes”), it is traditional to use “further” for the second such use, and “also” for the third and subsequent uses (for example, “Noting,” “Further noting,” “Also noting,” etc.).

In the GA and many other conferences, the preambular paragraphs are not numbered, whereas the operative paragraphs are. However, if there is only one operative paragraph, it is not numbered.

Informally the preambular paragraphs are referred to as PP1, PP2, etc., and the operative paragraphs as OP1, OP2, etc.

Preambular paragraphs serve to explain the basis for the action called for in the operative paragraphs. They can be used to build an argument, to build support, or to express general principles. Some lack of precision in the wording of preambular paragraphs is tolerable.

Operative paragraphs express what the conference has decided to do. Precise and clear language enhances political impact and facilitates implementation. Likewise, brevity is preferable, as it is politically much more powerful.

Tips on Ordering Paragraphs in the Operative Section

First, refer to the past. While references to the Charter and previous resolutions should be put in the preamble, if you want to give a report more emphasis you can put it in the first operative section.

Next, specify current actions, for example, “Decides,” “Decides also” and “Decides further.”

Today’s resolution format is, no doubt, a product of habit and tradition that can be traced to the days of the League of Nations (1919–1946). It is language and form that is accepted and understood by governments everywhere, despite differences of language, tradition and politics.

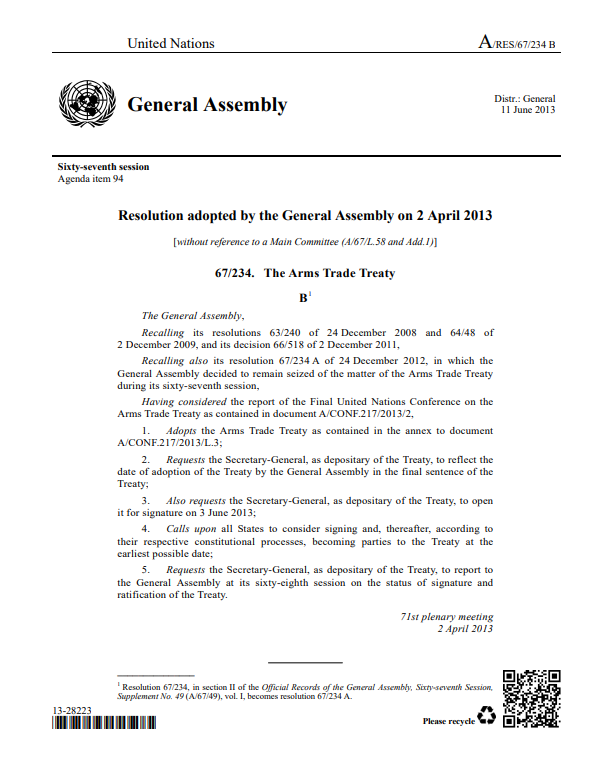

Example of a GA Resolution:

Example of a SC Resolution:

Tips on the Choice of Words

The most common and most neutral keyword that is used to begin an operative clause is “Requests.” This is typically used when a resolution asks the Secretary-General to do something.

When a GA resolution includes an operative clause that asks the SC to do something, it must remain polite; hence use of the keyword “Recommends” or “Invites” is desirable.

Sometimes the drafters of a resolution want to begin a clause with a word that contains more emotion. For example, “Calls upon” is stronger than “Requests” and “Urges” is considered to be even stronger. “Demands” expresses the highest level of emotion, but is rarely used.

Keys to Successfully Drafting Resolutions

In the early days of the UN, all draft resolutions were put to a vote. Now every draft resolution is discussed beforehand in informal consultations where some of the language is sacrificed in a spirit of compromise.

A key to successful drafting of both oral proposals and/or draft resolutions is to consult widely so as to know the concerns of others before you put pen to paper, and then to factor these into your draft so as to recruit sponsors and disarm opponents. When your draft resolution is written, you should again consult widely and be ready to modify it in response to the concerns of other delegations. This process will often ensure the draft’s acceptance when it is put to the committee for decision. At the very least, any points of serious disagreement will have been identified and isolated.

Checklist

Before you table a draft resolution, be sure that:

- Your delegation agrees that draft resolution is ready to be tabled.

- Your resolution is supported by other delegations. This includes not only those with whom you usually associate but also others who support the thrust of the resolution. You need to know the resolution’s chances of success before it is tabled.

- Delegations you want to co-sponsor the resolution have been consulted throughout, that they are happy with the final text and are willing to co-sponsor it.

- You are confident in the wording of the resolution. This relates both to its content and how it is expressed. If you are not proficient in English you should consult someone who is.

- You have tabled your draft resolution with the Model UN Secretariat or committee bureau ahead of time so that they can distribute the text to all the delegations before the resolution is introduced.

Reviewing the Text after it Is Tabled

In the case of long texts on which there are many proposals for amendments, the committee (or plenary), under the Chair’s leadership, will undertake successive readings of the text. The Chair will invite the committee’s attention to the first paragraph (or, if the Chair expects the text to be contentious, the first sentence or first part of the first sentence). If there are no proposals for amendment, that passage is considered to have been provisionally agreed. The Chair will then invite the committee to consider the next passage. If amendments are proposed, these will be discussed and, if there is agreement, modified wording will be incorporated into the text. This new text will then form part of the provisionally agreed draft.

If, on the other hand, the committee is unable to reach agreement on the proposed amendment within a reasonable time, the disputed words will be enclosed in square brackets and the committee will proceed to the next passage.

At the conclusion of the first reading, the text will consist of provisionally agreed upon passages and words or passages in square brackets. Each set of square brackets may enclose a single word or several words, or alternative words or phrases, separated by a slash (/). This means that some in the committee prefer one option, while others prefer the alternative.

Soon after completing the first reading (but sometimes after allowing time for informal consultations), the Chair will invite the committee to proceed to a second reading of the text. This time, the committee will not re-examine the provisionally agreed text. It will instead proceed to the first set of square brackets and the Chair will seek new ideas on their content. This is often the case because the delegates who had objections have in the meantime:

- Seen how the whole text is developing and consequently are now untroubled by the bracketed word(s)

- Given the matter further thought (in some cases after discussing the issue with other delegations informally and/or consulting their headquarters) and come to the conclusion that they do not wish to maintain their objection, or

- Held consultations with other interested delegations ending in informal agreement to change the word(s) at issue.

If the committee can agree to accept the word(s) in question, or different word(s) instead, the square brackets will be removed and the newly agreed text will now form part of the provisionally agreed whole. This process is known informally as “getting rid of square brackets.” If, on the contrary, agreement cannot be reached, the contested word(s) will be left in square brackets. Either way, the Chair will invite the committee to proceed to the next set of square brackets and again attempt to reach agreement. This process will continue to the conclusion of the second reading, with the result that the text is fully agreed or substantial progress has been made towards agreement.

Thereafter, a third and any successive readings will be conducted in the same manner until the text is approved. A text that goes through several readings may be called a “rolling text.”

The text provisionally agreed is “provisional” in the sense that all concerned understand that in many cases delegates cannot definitively approve partial texts. They need to see the whole before knowing whether any of the parts are acceptable.

During consultations the facilitator or sponsor of a draft resolution can circulate “compilation texts” that reflect the evolution of the negotiations and the different positions of Member States in detail. After each round of negotiations, revisions of the text are compiled.

This illustration shows the standard elements for compilation texts. Please note that the example here is fictional:

Compilation Text as of 21 October 2016 (Rev. 3) The General Assembly,

PP1 Reaffirming its previous resolutions relating to the issue of chocolate, including resolutions 46/77 of 12 December 1991 and 63/309 of 14 September 2009;

PP2 Recognizing the role of the General Assembly in addressing the issue of chocolate, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations;

PP2 (Alt) Recognizing also the need to further enhance the role, authority, effectiveness, and efficiency of the General Assembly; [Proposed: Liechtenstein]

OP1 Takes note of the report of the Secretary-General on “Chocolate for All”;

OP2 Expresses its support for the active ongoing [replace : EU] promotion of Swiss [Delete: EU, G-77] chocolate for the physical and mental [Add: ROK] well-being of people;

OP3 Calls upon the Secretary-General to mainstream the use of chocolate by providing chocolate in all meetings as a tool to increase happiness throughout the United Nations system and its operational activities;

OP3 (bis) Recognizes the positive contribution of increased consumption of chocolate to the economy of cocoa farmers in developing countries; [proposed: G-77 / supported: Mexico]

OP4 Encourages Member States to promote the consumption of chocolate; [Comments: US, JPN, CANZ will get back on the paragraph after checking with their Ministry of Health]

OP5 Decides to declare 2020 the International Year of Chocolate; (agreed ad ref)

OP6 Requests the Secretary-General to submit a report on the implementation of the present resolution including recommendations for future action at the 84th session of the GA. (agreed)

Terminology

“To place brackets around text” or to “bracket text” indicates the text is not yet agreed.

“Getting rid of square brackets” indicates a need for more work towards agreeing on the disputed words or passages.

“A clean text” is one without square brackets that is acceptable to all who participated in its drafting. However, there is a strong convention against re-starting discussion on any part of provisionally agreed text, as it can easily lead to prolonged negotiation. Nevertheless, “all conferences are sovereign.” This means that if delegates agree there is a good reason, a committee may decide to reconsider part of the provisionally agreed text. It is unlikely to agree to such reconsideration unless the proposal is acceptable to all delegates.

Tips for Model UN Conferences

The review of draft resolutions and the consideration of amendments is the most time-consuming element of a conference. In addition, it is typically a time during Model UN conferences when Rules of Procedure are frequently invoked which further slows down the process of taking action on a draft resolution.

Given the time limitations of a typical Model UN conference, the amount of time needed to take action on agenda items can be significantly reduced by:

- Reducing or limiting the number of resolutions that are tabled on a particular agenda item.

- Making sure that the sponsor(s) of a draft resolution have consulted with other delegations to make sure it has wide support by other delegations. This includes not only those with whom they usually associate but also others who support the thrust of the resolution. It is critical for the sponsor(s) of a resolution to know whether their resolution has a chance of success before it is tabled.

- Reviewing the text of a resolution line by line. In many Model UN conferences, amendments are made randomly rather than as a result of a systematic review of the document. Following a more rigorous review as outlined above can help identify where delegates are in disagreement and allow more time for informal consultations to resolve their difference.