- عربي

- 中文

- English

- Français

- Русский

- Español

CTC 20th Anniversary | An Interview with David Wells on Political Analysis and Research

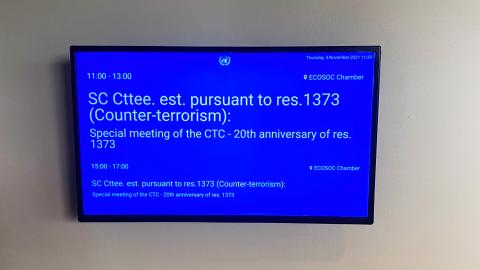

2021 marks the 20th anniversary of the adoption of Security Council resolution 1373 (2001) and the establishment of the Counter-Terrorism Committee. As part of the year of commemoration, CTED experts reflect on their work.

David Wells is a Political Affairs Officer and Head of the Political Analysis and Research Unit at CTED. Mr. Wells has been with CTED for over four years. This interview has been edited for brevity.

What motivated you to come to the United Nations and to CTED?

Mr. Wells: I've been working in counter-terrorism, basically, since university. So my first job out of university was working for one of the UK intelligence agencies. And straightaway (because this was in 2005, just after the “7/7” attacks in London) pretty much everyone who joined in that kind of stream (the intelligence analyst stream) was pushed into counter-terrorism. So it's something that I've worked on pretty much constantly for the last 16 years, working in the national context in the UK, then the national context in Australia, and ending up moving more into kind of a research policy space rather than an operational space. And it felt to me that the next logical step (having worked in national contexts and to an extent, regional contexts) was to think about the international context and the global impact of counter-terrorism as a whole. So the UN, and CTED, seemed like the logical place to go, and I've been here for the last four years.

What is the role of the Political Analysis and Research cluster at CTED?

Mr. Wells: We're in charge of coordinating all work on trends, issues and developments connected to terrorism and counter-terrorism, as well as anything in relation to CTED’s mandate, which is obviously broad and expanding all the time. So, broadly speaking, our role is to engage with all our colleagues who speak every day to Member State Governments, international and regional organizations, the private sector, and civil society, and take all those inputs and synergize them. But then, also, the team is responsible for engaging with academia through our Global Research Network. And so the idea is that we sit in the middle of those two streams of work (again, with a global focus), working with all partners engaged on counter-terrorism. The idea is to synergize all that, analyse it, and then draw broad conclusions about the key trends that the Counter-Terrorism Committee, Member States, our UN partners and policymakers need to be aware of.

So that can take a number of different forms. It can be publications (probably most visibly) but also, a lot of the time, we put together events, workshops, and round tables (and particularly since COVID we've done a lot of those online). But the idea is to mainstream those trends and the kind of analysis that the team pulls together throughout CTED’s work.

What is the Global Research Network?

Mr. Wells: The Global Research Network has been around since February 2015. The idea is for CTED to be a kind of focal point for engagement with academia working in this space. So we partner with over 100 organizations from around the world, working on lots of different aspects of the counter-terrorism and terrorism picture. It’s a fairly informal network, in some ways, but we do come together for formal meetings. We held one most recently in September 2021 with the Counter-Terrorism Committee. The general idea is that it's “the best and brightest minds out there” in the research field, directly engaging with CTED and providing us with their research. But it also means that if we're looking at a new issue (for example, over the last two-to-three years, we’ve been looking closely at the rise of terrorism motivated by xenophobia, racism and intolerance), we have a network of individuals who are working in that space for different institutions whom we can call on, consult with, and seek their expertise. And that expertise can be shared at Counter-Terrorism Committee meetings and in various other forums.

What would you say the main trends have been since 2001?

Mr. Wells: I think if I were going to summarize the last 20 years into three key trends, I think the first one is that there's been a waxing and waning of both the terrorist threat and the level of violence posed by terrorism, but also significant changes in its geographical centre. So, at any point really over the last 20 years, we've seen the terrorist threat emerging in different regions and different States (often fragile States facing conflict or other crises, where terrorist groups can exploit those conditions and either find a safe haven or, in more recent times, control territory). So we've seen dramatic shifts in where that kind of centre of gravity is, but also shifts in the level of violence that terrorism has posed. So I think, for sure, over the last 20 years there have definitely been points where maybe the consensus has been that terrorism is less of a problem than it was before. Certainly in 2011, and 2012, I think there was such a consensus, after the death of Bin Laden and the death of Anwar al-Awlaki, that maybe terrorism wasn't going to be a global problem anymore and that perhaps our attention could turn elsewhere. Obviously, only two years later, suddenly, terrorism was the biggest issue on the global agenda. So there have been big shifts in terms of the threat base level and the location. I think it's probably fair to say that if we look at where the terrorism issue is now versus where it was 20 years ago, we have made significant progress. But there's still a lot more work to be done. So I think that's the first key trend.

I think the second key trend has been the huge increase in the global counter-terrorism architecture. Obviously, the UN (and especially the Security Council) has been at the heart of a lot of that. But again, looking back to 2001, and looking at how many Member States actually were dealing with terrorism in any meaningful way (at the criminal justice level, legislatively, all those different ways) the number now is vast, and it's something that has also affected so many different Member States. We have an architecture that's evolved over time. And it's now overarching and fairly huge in its scope and scale. And I think what's happened simultaneously with that (and I guess this is linked to the first point) is that terrorists have continued to evolve their modus operandi in response to our counter-terrorism approaches. What we now see today where Member States have developed counter-terrorism architecture are predominately “lone actor” attacks and simple attacks using basic weapons.

And then I think the third thing is the evolution of the Internet and the role of ICT over the last 20 years, which has been transformative. During my first few years in counter-terrorism, it was very much about telephony, it was about landlines to a certain extent in terms of the kind of intelligence that we were looking at. And now everything's online, and we're all online 24/7. And we've addressed that shift a lot in the context of foreign terrorist fighters and the role of social media in terms of analysing and recruiting, but it's across all spheres and it has obviously changed the way we can do counter-terrorism. And the whole field of international cooperation is obviously radically different. Now it's instant. We can communicate with partners all around the world. The ability of CTED to continue to perform its assessment function virtually over the last 18 months, during the pandemic, would have been almost impossible to imagine even 10 years ago. So I think that the Internet has just fundamentally changed everything that we do and how we interact with each other. And that's definitely the same for terrorism and counter-terrorism.

Member States have been focusing on a number of major challenges, including the pandemic, and I think that one of the big challenges over the next few years will be making sure that counter-terrorism is adequately resourced.

How do you decide what trends to look at? Does the Security Council ask you to look at specific things? Where do you get your information?

Mr. Wells: We try to be as proactive as possible. And I think that's part of the challenge: to be proactive without at the same time pushing new issues onto the agenda at the expense of existing issues that are significant and aren't being dealt with either. So it is really about that synthesis; first and foremost, the information we receive through our dialogue with Member States, but then adding that to information we receive from colleagues who've been to different parts of the world on different missions and at different conferences and engaging with different partners and asking those questions and hearing about what they've learned. So I think there are lots of different sources of information, obviously, for the team as well. We spend a lot of our time engaging with the research community to see what they're looking at. But there are instances where researchers are looking at issues because Member States are funding them or regional bodies are funding them so it's quite a symbiotic relationship. So it is a difficult decision to say “This is the key thing we should look at”. And I think it’s also about partnerships, about working with colleagues, but working with other communities as well to understand the issues that affect them most. I think it’s also thinking about issues where CTED is well positioned to work (or perhaps where there aren't existing international standards, good practices, and that sort of thing). So it is trying to think ahead a little bit, a bit of horizon scanning and trying to understand what's coming next in terms of either a regional or nation-specific problem or a technologically driven trend, or a broader thematic challenge. One of the key challenges is to try to balance that while still giving significant attention to the recurring challenges that we've seen throughout the last 20 years. And there are lots of problems connected to terrorism that we haven't really dealt with at all. Sometimes the shiny new things can distract from core work around grievances, drivers to radicalization, human rights issues connected to counter-terrorism (issues that have been around throughout the last 20 years and still haven't really been adequately addressed). So I think the final challenge is the global nature of what we do, there will always be challenges that are region-specific. And so if you look at say, some of the terrorism issues that parts of Africa are facing, you see that their challenges and the issues that they face will be different from those faced by, say, South-East Asia. And that's about Member States’ capabilities, but also about the available technology and other region-specific factors. So it's very hard, I think, to just talk globally. We have to be nuanced and provide context around that.

What have the recent trends been, and what light does this shed on what terrorism and counter-terrorism could look like in the future?

Mr. Wells: I think the first overarching change (particularly in the last six or seven years) was the FTF issue, which is obviously an incredibly broad issue. There are huge issues around evidence (whether digital, battlefield, or more conventional) and huge issues around violent extremist prisoners and how to deal with those individuals if they're in detention. I think it's also shed a lot of light on the gender issue in particular and strengthened our understanding of the role of women in terrorist and violent extremist organizations. Obviously, in the current context, it’s related to issues around repatriation. And recidivism will be a really big issue moving forward because the size of that FTF cohort is so enormous and so many of them are so young that there are big questions around what happens next to individuals who may have returned to their countries of origin or nationality and served prison time. A lot of the CTED team has worked closely on these topics over the last few years.

I think, secondly, an issue that we've worked on a lot as a team (and it's been increasing in prominence) is the issue of terrorism motivated by xenophobia, racism and intolerance. I think this is an issue that has been bubbling under the surface for quite some time. The global focus had been on ISIL and, to an extent, Al-Qaida and the FTF issue. And, as that phenomenon began to wane, there was suddenly a realization that perhaps there was a broader issue that was more domestic in its roots, but still transnational in terms of connectivity, and that Governments hadn't been paying much attention to. And it was certainly going to create significant challenges. So we’ve seen some pretty major terrorist attacks (less so over the last 18 months of the pandemic but certainly in the two-to-three years before that) across Europe, in Australasia, and obviously in North America, too. So that's a really growing issue that a lot of Member States are concerned about, and I think it throws up a lot of questions in terms of the applicability of the existing international frameworks to a different kind of terrorist threat. Many of those frameworks had been tailored very specifically to ISIL and Al-Qaida-related problems. So it's still not clear, and I think that's one of the big questions moving forward. A lot of progress has already been made over the last two years. And CTED has been at the forefront of that, and particularly around financing and the issue of the use of the Internet. But there's a great deal more work to be done in that space.

And then, thirdly, there’s the COVID-19 issue. CTED has published three analytical papers on that topic. I think, broadly speaking, our analysis is that it's a little early to say what the impact of COVID-19 has been so far, but that the long-term impacts do look worrying when we think about the potential for greater polarization, alienation, and online radicalization (all of which have received a huge amount of attention over the last 18 months). And there’s also the relationships established between new groups, their pushing of conspiracy theories in relation to the pandemic, and how those groups might be connected to violent extremist and terrorist groups.

So that's a big concern, I think, looking ahead. It's kind of a compounding crisis that has exacerbated a number of existing trends. But it has also brought to the surface broader challenges around inequality and competition for power, which are all going to make counter-terrorism a lot harder moving forward. One of the things we've highlighted is the economic impact of the pandemic, including the potential impact on resources available for counter-terrorism and CVE. The pandemic will increase the number of people around the world who are struggling financially and looking for meaning or alternative sources of income and could be potentially recruited by terrorists and violent extremist groups.

So those are the three core trends. Zooming out again to think about the last 20 years and where we are in 2021, It's a very challenging environment in terms of the priority of counter-terrorism. Member States have been focusing on a number of major challenges, including the pandemic, and I think that one of the big challenges over the next few years will be making sure that counter-terrorism is adequately resourced. That hasn't generally been a problem for the last 20 years in most parts of the world. But there will be greater challenges around that. So, yes, there has been significant progress in responding to the terrorist threat in terms of creating a global counter-terrorism architecture. But a significant threat still remains. And I think, in this age of compounding crises, the recent reallocation of resources that we’ve seen may not be positive for counter-terrorism over the next few years.

How did the Security Council decide that it needed to look at trends and have a research arm?

Mr. Wells: Security Council resolution 2129, that was adopted in 2013, was basically the first time that the Council had asked CTED to look at the issue of trends, research and analysis. So, up until that point, there had obviously been a really significant focus on the assessment process and engagement with Member States. And I guess one of the, I mean there’s lots of huge positives about that process and the level of engagement it gives CTED and the Committee. But I think one of the challenges with that is that it’s a very “Member State by Member State by Member State” approach, and I think one of the things that that resolution recognized was that for an organisation like CTED, we’re sitting on a wealth of information derived from our engagement with Member States, and over the years, our engagement with other partners as well. And so having a research and analysis function within CTED with a role to essentially zoom out and say “Okay, great on a national level, you're looking at this specific Member State that you've engaged with, or this specific region, but how can we compare that region (or subregion) with a different part of the world? Or can we look at a thematic issue across a whole region or globally?” And so I think what's really unique about the Political Analysis and Research Unit is that we have a completely global mandate from the Security Council to look at trends entirely globally. And that was recognised by the Council in 2017 through resolution 2395, which reaffirmed and strengthened CTED’s trends mandate.

Is there a standout moment or something you’re really proud of over the last four years that you’d specifically like to highlight?

Mr. Wells: I can think of two things, in particular. The first is the work on terrorism motivated by xenophobia, racism and intolerance, because it was a challenge. There were a lot of sensitivities involved, and a lot of things we had to navigate while working on that issue. It wasn't as simple as saying, “We've identified this as a trend of concern, and therefore we're going to have a publication on it, we're going to hold an event. And we're just going to move forward”. It was a really long process to try to sensitize Member States to the fact that there was a concern around that issue, while also understanding the various pressure points and issues involved (particularly around the terminology question). A lot of that work was done behind the scenes for a couple of years before we finally published something. In 2020, we published two reports on that issue. And the second really gratifying moment came in October in 2020, when we had the first CTC open briefing on the same issue and we were able to see how far we'd come over the previous two, or two-and-a-half, years. We were able to organize a dedicated CTC meeting on a topic that had been so sensitive up to that point, with real concerns about CTED working in that space. It was very gratifying not only to be able to listen to the contributions of civil society, academia and the other parts of the UN but also to see how many Member States not only spoke about their own work on the issue or their own concerns about it, but also commended CTED for its work. There was a real sense that we were leading that discussion and that we had pushed the issue onto the international stage for the first time.