At the end of May this year, I visited the Gaza Strip for the first time in my life. I was there to support the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) with their work on advocacy, policy influencing and resource mobilization. While visiting a school, I met two young people, Deema and Kareem, who were kind enough to show me around. Deema, Kareem and their friends dream of becoming teachers, doctors or engineers. They told me that their school represented their best, and only, hope for a better future, one in which they could realize their ambitions and reach their full potential. However, Deema and Kareem fear they will not be able to achieve their dreams because their school—managed by UNRWA—is seriously underfunded due to significant cuts in financial support to the Agency.

Let me put things in a global perspective for you: 263 million young people between the ages of 6 and 17 are out of school, and the same is true for 60 per cent of young people between the ages of 15 and 17.1 Some 617 million young people worldwide lack basic mathematics and literacy skills.2 And for girls, the situation is even worse. Far too often, in fact, they are marginalized and left out of school simply because of their gender. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 15 million girls of primary school age will never get the chance to learn to read or write in primary school, compared to about 10 million boys.3 If you think that’s bad, I’m not done: if you are a girl and live in a conflict-affected or rural area, come from a poor family or have a disability, you are 90 per cent more likely than boys to miss secondary school.4 All these statistics provide clear evidence that significant transformations are still required to make education systems more inclusive and accessible.

Access to quality education is not only beneficial for young people but also for the world.

A plethora of barriers prevents young people from accessing quality education. Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, especially girls, might be forced to work, manage their households or care for their siblings. Young people could be affected by conflicts and emergencies; child marriage; pregnancies at a young age; disabilities; and a lack of access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene facilities. Whatever the circumstances, however, everyone—including Deema and Kareem—has a right to learn and receive a quality education. Access to quality education is not only beneficial for young people but also for the world. Educating boys and girls increases productivity and facilitates economic growth; knowledge about sanitation, immunization, nutrition and general health can save lives; and quality education provides girls and boys with the skills they need to take on leadership roles at local and national levels, enabling them to take part in decision-making on matters that affect their lives and their communities. If that is not convincing enough, young people who are educated on human rights can defend themselves and others; support their personal and their communities’ health and well-being; and contribute to building stronger families, communities, nations and, ultimately, the world.

At the United Nations, we are very aware of the potential held by the 1.8 billion young people living in the world right now. We want them to realize this potential. In 2015, the Member States of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for the people and planet. The widely shared motto has since been “Leave no one behind”. Leave no one behind in poverty; leave no one hungry; leave no one out of decent work and economic growth; and, crucially, leave no one without access to quality education. As part of this global agenda guiding the whole world towards a better future, we made a commitment to achieve the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG): to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”.

We want to guarantee that all girls and boys can complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education. We need to support those who are in dire need of education so they are able to compete in the continuously changing job market and the fourth industrial revolution. With more than 64 million young people unemployed today and another 145 million young workers living in poverty, we cannot afford to continue exacerbating the skills gap.5 We must bridge this gap through all means necessary.

Education needs to effectively combine knowledge accumulation, life skills and critical thinking, enabling young people to navigate changing economies rapidly and successfully.

Yet, in the midst of this learning crisis, we have the solution right before us: schools should provide education to prepare young people for both life and work. Educational attainment alone, however, does not provide the expected social and economic returns. Education needs to effectively combine knowledge accumulation, life skills and critical thinking, enabling young people to navigate changing economies rapidly and successfully. Education must also enable young people to adopt sustainable lifestyles and contend with climate change—the greatest challenge of our time. Education needs to reflect our world’s diversity, including marginalized groups, and ensure gender equality. It should promote a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity.

In our increasingly complex and interconnected world, learning is key to lifelong personal and professional success. Learning enables us to seize and create opportunities. Out of interest or necessity, each one of us seeks new knowledge or training to acquire, update and enhance competencies. This is especially critical for the current generation of young people, given the rapidly changing future of work, characterized by technological advancement and the need for an accelerated transition to green and climate-friendly economies. The creation of new technologies is also transforming the way we learn. However, while such technologies support learning for many, access to them is not always universal. It is our duty to ensure that technology leaves no one behind. Only when policies adopt a life cycle approach, and quality education and training are adequately funded and equally available to those who are marginalized, will individuals have the agency and capacity to act independently and make free choices.

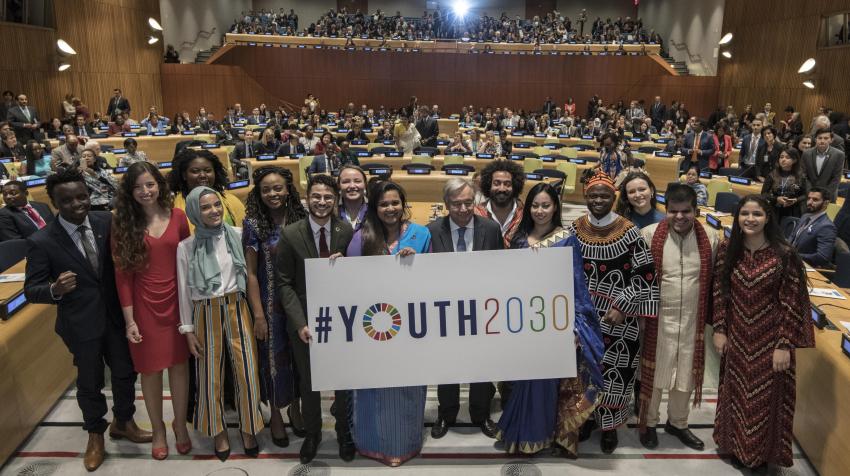

To achieve this ambitious but reachable goal, we need to transform education. We must refocus our efforts to improve the quality, eliminate deep disparities, and invest more in infrastructure and access. How are we doing this? Here at the United Nations, working with and for young people is at the centre of all we do. In September 2018, Secretary-General António Guterres launched Youth 2030, the United Nations Youth Strategy. Youth 2030 is the first document of its kind at the United Nations. It envisions a world in which every young person’s human rights are realized, where young people are empowered to achieve their full potential; it recognizes young people’s strength, resilience and their positive contributions as agents of change. Education is one of Youth 2030’s key priorities: we are advocating for quality education by engaging Member States and other partners to ensure universal access to such education, and to develop and deliver quality and inclusive education for young people that is learner-centred, adopts a lifelong learning approach, is relevant to their lives and the social and environmental needs of their communities, and promotes sustainable lifestyles and sustainable development. We are also promoting non-formal education by advancing youth policy frameworks that support non-formal education and its role in the development of young people’s knowledge, skills and competencies.

As I said earlier, the United Nations works with young people who are taking matters into their own hands. Since my appointment as the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth in 2017, I have met a large number of inspiring young leaders. These leaders are working hard to ensure that no one is left without quality education. No act is too small. One example is Amélie Jézabel Mariage, a Young Leader for the SDGs. Amélie is a champion of inclusive education in Spain and globally. She is also the co-founder of Aprendices Visuales—an award-winning tech non-profit that uses the power of visual learning to teach children. Together with her partner, Miriam Reyes, Amélie developed a series of e-books and applications with pictograms in five languages to teach autonomy as well as social and emotional skills, reaching 1 million children who are experiencing barriers in accessing inclusive education.

On 12 August, we will celebrate International Youth Day. This year’s theme, “Transforming education”, highlights the world’s efforts—including those pursued by youth themselves—to make education more inclusive and accessible for all young people. It will examine how Governments, young people, and youth-led and youth-focused organizations, as well as other stakeholders, are transforming education into a powerful tool to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Efforts should be directed to developing the right mechanisms to empower and educate young people.

Transforming education is no easy task, but it is an imperative one. Efforts should be directed to developing the right mechanisms to empower and educate young people. Governments may have a lead role in providing a lawful environment that safeguards and promotes human rights. Civic, religious, educational, business, labour, cultural and social organizations at all levels of society have important roles to play in reinforcing respect for human rights, as well. We need to unify our efforts in securing access to quality education for all.

Though my mission to the Gaza Strip has ended, I will not stop advocating for the rights of all young people—including Deema and Kareem—until they all are able to realize their full potential.

Notes

1. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 263 Million Children and Youth Are Out of School. Available at http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school (15 July 2016).

2. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 617 million children and adolescents not getting the minimum in reading and math. Available at https://en.unesco.org/news/617-million-children-and-adolescents-not-getting-minimum-reading-and-math (21 September 2017).

3. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 263 Million Children and Youth Are Out of School. Available at http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school (15 July 2016).

4. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “Education for All Global Monitoring Report”, Policy Paper, No. 21 (Paris, 2015). Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233557_eng.

5. International Labour Organization, Youth Employment. Available at https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/youth-employment/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 06 August 2019).

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.