Rendering of the United Nations Headquarters, drawn by Hugh Ferriss for the Board of Design, 1947.

This exhibition was organized in connection with the 70th Anniversary of the United Nations in 2015.

It commemorates the founding of United Nations Headquarters (UNHQ) in New York by showcasing archival images of selected design proposals developed in 1947 by a team of ten international architects led by Wallace Harrison as well as images taken during the construction of the compound between 1949 and 1952.

The exhibition also includes images of the renovated UNHQ, which underwent a major and long delayed refurbishment between 2008 and 2014. The Dag Hammarskjöld Library, the fourth building on the site, was not renovated because its location and fragile structure prevent the building from being properly secured. The future of the Library is uncertain.

The purpose of the renovation was to make UNHQ safe, secure, sustainable, modern, and accessible, while respecting the architectural integrity of the original design. Michael Adlerstein, the former Chief Historic Architect for the United States National Park Service, was appointed Executive Director of the Capital Master Plan.

...For the people who have lived through Dunquerke, Warsaw, Stalingrad and Hiroshima, may we build so simply, honestly and cleanly that it will inspire the United Nations, who are today building a new world, to build this world on the same pattern...The world hopes for a symbol of peace. We have given them a “workshop for peace”.

—Wallace Harrison, Director of Planning, 1947

UNHQ needed major repairs: the roof of the General Assembly and the green-glass façades of the Secretariat Building were leaking; the heating and air conditioning systems were obsolete; the buildings had fallen below fire and safety standards; asbestos was a major health hazard, and security was an increasing concern.

As a result of the renovation, the energy consumption of the entire compound has been halved; all the glass, including the revolving doors, are now blast-resistant; and the electronics infrastructure has been upgraded. Extensive structural enhancements were necessary to increase the level of protection in the Conference Building because it overhangs the FDR Drive. To better accommodate the 8,000 meetings held every year, several new conference rooms have been added. The compound now meets current New York City building and life safety codes.

Many of the photos on display are included in The United Nations at 70, Restoration and Renewal, a book published in 2015 by Rizzoli International in collaboration with the United Nations.

This exhibition is presented by the Department of Public Information with the generous support of the Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations.

Planning and Building UNHQ

Construction of the United Nations Headquarters (UNHQ) began in 1949. When the work was completed in 1952, the Complex included three buildings: the Secretariat, the General Assembly Building, and the Conference Building. The Dag Hammarskjöld Library was added in 1961.

The choice of the United States as the host country was made in January 1946 in London during the first session of the newly created General Assembly. Proposals for the actual site were numerous, including San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Boston. In New York, Flushing Meadows was an option as it had languished unused since the 1939 World’s Fair. In Connecticut, Fairfield County was a favorite.

The final choice was a site in mid-town Manhattan, north of 42nd St, an 18-acre expanse of slaughterhouses and tenements along the East River. On that same six block site, William Zeckendorf, a renowned real estate developer, had envisioned a massive multi-use complex to rival Rockefeller Center. He had already selected an architect to design it, Wallace Harrison, who had worked on Rockefeller Center and on the buildings of the 1939 World’s Fair. But Zeckendorf lacked the funds to close the deal.

At the same time, the Rockefeller family was trying to attract the United Nations to New York and was scouting for a site. Harrison acted as a go-between and arranged the sale of the parcel to the United Nations. Zeckendorf got his asking price ($8.5 million). The Rockefellers wrote the check.

In December 1946, the United Nations Headquarters Committee recommended the acceptance of the site and the financial gift. The General Assembly approved the request, and East Midtown site became the location of the permanent UN headquarters.

An international Board of Design was approved by Trygve Lie, the United Nations’ first Secretary-General, who appointed Harrison to direct it. Only UN Member States were entitled to contribute architects to the team. For this reason, some prominent names were excluded, including Alvar Aalto from Finland, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, both born in Germany.

The Board of Design met 45 times and reviewed 75 proposals. The final design was presented on 21 May 1947. While the modernist proposal was approved, its scope was later reduced due to the UN’s tight budget.

Designing UNHQ

Ten architects were selected for the team: Le Corbusier, France; Oscar Niemeyer, Brazil; Sven Markelius, Sweden; Nikolai D. Bassov, USSR; Gaston Brunfaut, Belgium; Ernest Cormier, Canada; Howard Robertson, United Kingdom; Ssu-Ch’eng Liang, China; Gyle A. Soilleux, Australia; and Julio Vilamajó, Uruguay. Wallace Harrison, USA, led the team as Director of Planning. Shown in the photo the architects with assistants. UN Photo

The fundamental forms of the buildings as eventually constructed were Le Corbusier’s and Niemeyer’s. The design process was not always smooth. Le Corbusier, the most prominent of the group, announced his vision from the very first meeting in February 1947. His design included two structures: a minimalist skyscraper on stilts, and a horizontal conference building, as long as the skyscraper was tall and as deep as it was broad, that would include four chambers on one floor. Nobody objected to the choice of a high-rise with an aluminium-and-glass façade – symbol of a more transparent world order. However, the Conference Building drew immediate criticism. The architects argued that two stories were needed to keep UN staff and visitors separate and highlighted that the General Assembly – the world’s Parliament – should be a free-standing, separate building.

Le Corbusier’s proposal number 23A with the General Assembly in the middle of the site.

Niemeyer’s proposal (number 32)

The compromise design the group agreed on. Numbered 23B, it is a combination of 23A and 32.

Eventually, Niemeyer proposed a design that his colleagues preferred. It included three structures, standing free, and a fourth lying low behind them along the river’s edge. He separated the General Assembly and fitted the Conference Building behind the Secretariat. His design also included an office skyscraper on the north end of the site that would host delegates and UN subsidiary bodies. This structure was later cancelled due to budget constraints.

Le Corbusier complained about the location of the General Assembly that Niemeyer had placed close to the corner of First Avenue and 42nd Street. Despite the objections of some of his colleagues, Le Corbusier insisted that it had to be in the middle of the site. In the end, Niemeyer modified his original proposal and moved the General Assembly to the center of the compound.

Secretariat

Construction: 1949 - August 1950

544 ft tall (166 m); 285 ft wide (87 m), 72 ft deep (22 m)

39-story office building (45 stories in the original design. Shortened because of budget constraints)

Staff moved into the building in 1951. Over 3,000 employees in the Secretariat by 1952

Renovation: 2010- June 2012

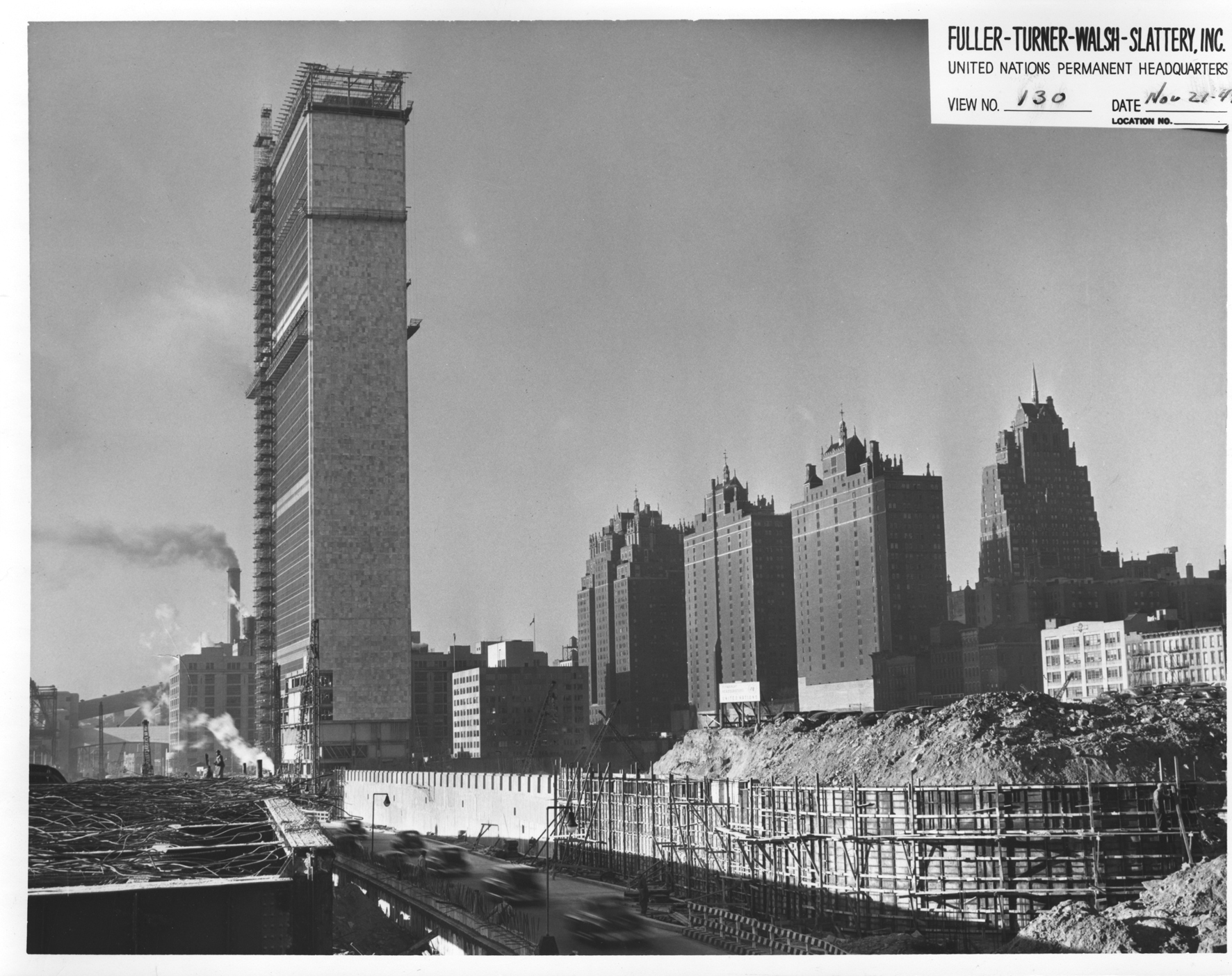

The white and emerald green Secretariat was the first skyscraper in New York to have all-glass curtain walls. It resembled an ice palace and stood out in stark contrast to the brick exteriors around it and to the ornate skyscrapers that dominated Manhattan’s skyline. The office glass block on the compound of the new world parliament was the most radical proposal to come from the team of architects.

No building in the city is more responsive to the constant play of light and shadow in the world beyond it…No one had ever conceived of building a mirror on this scale before Lewis Mumford, New Yorker, 15 September 1951

Secretariat

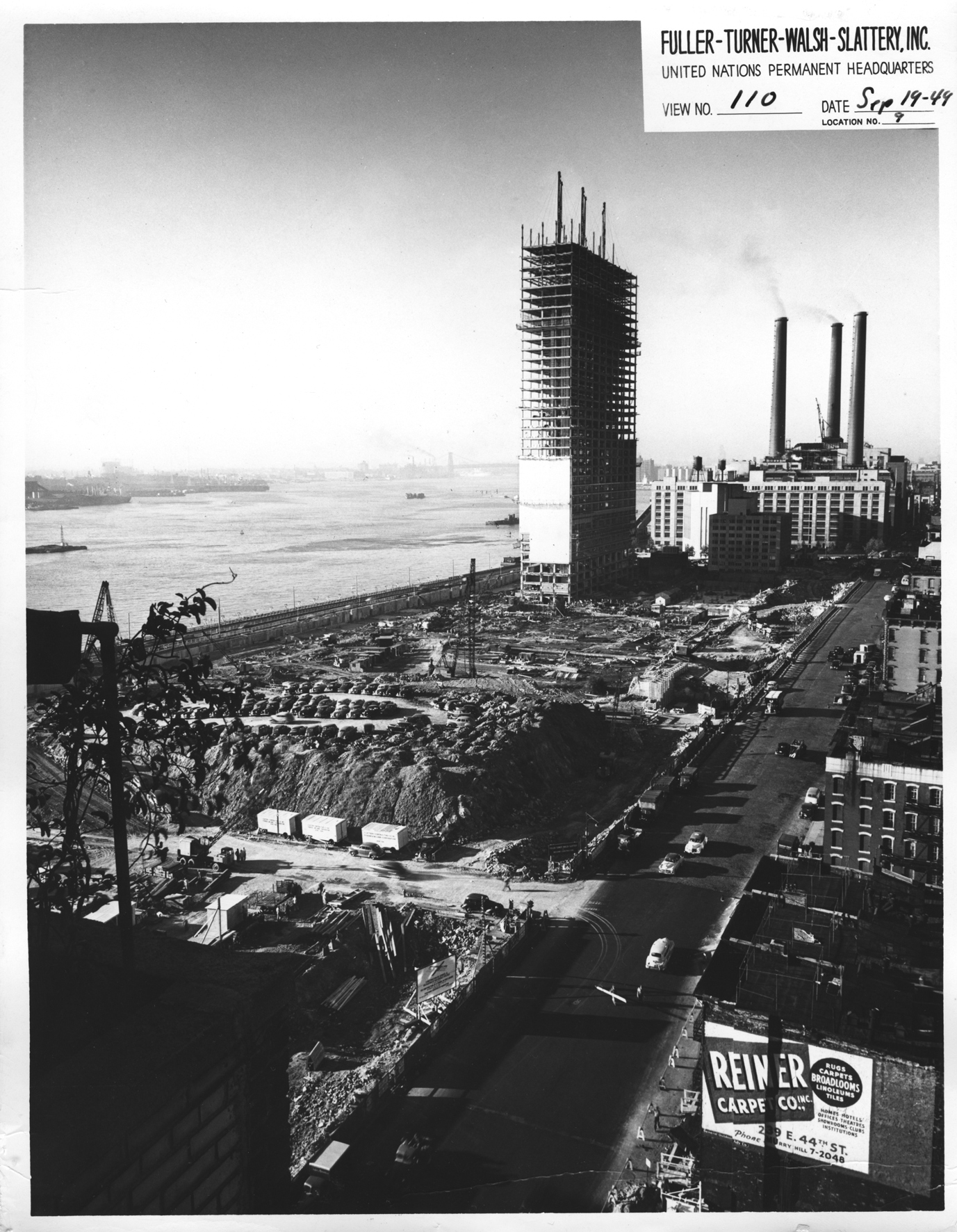

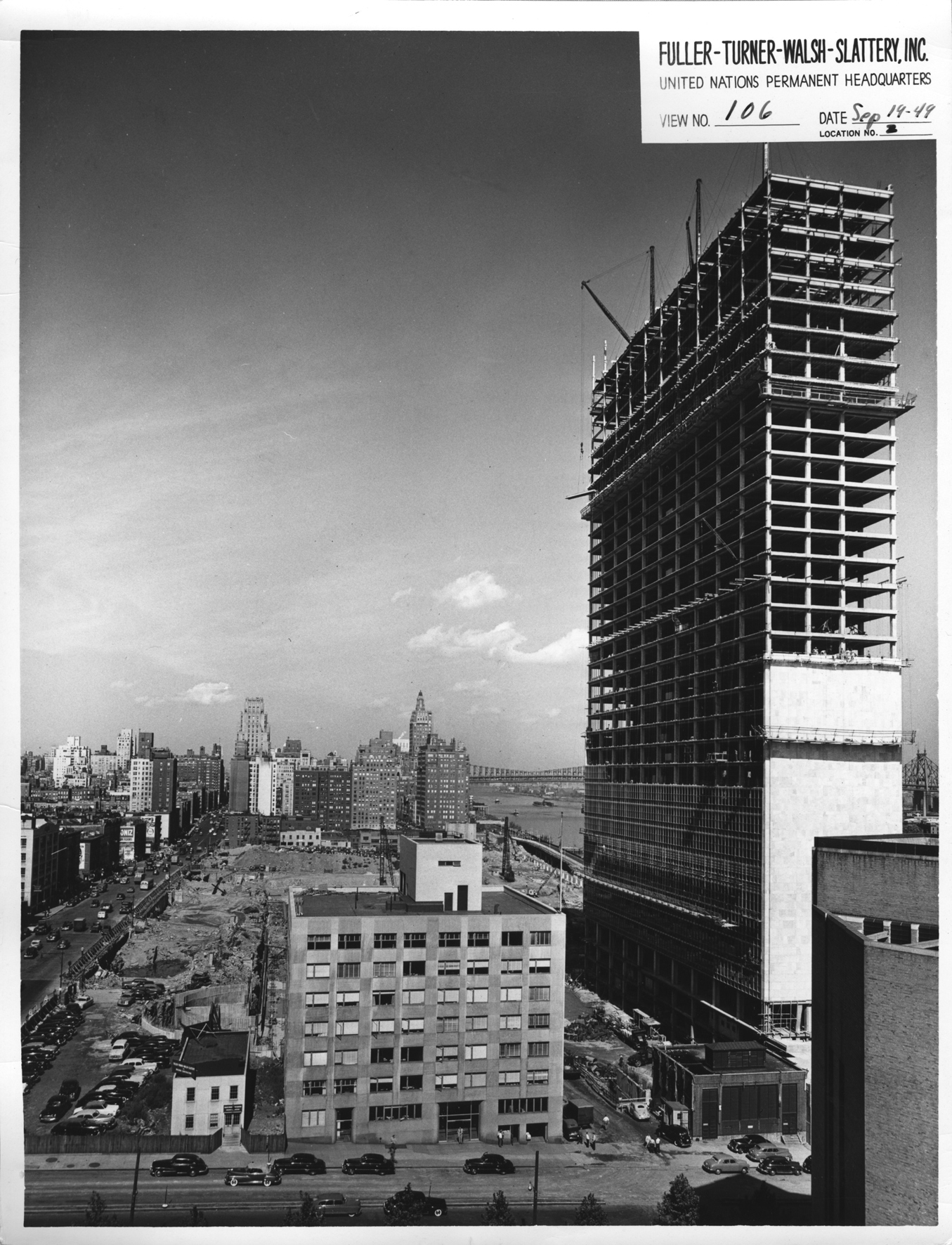

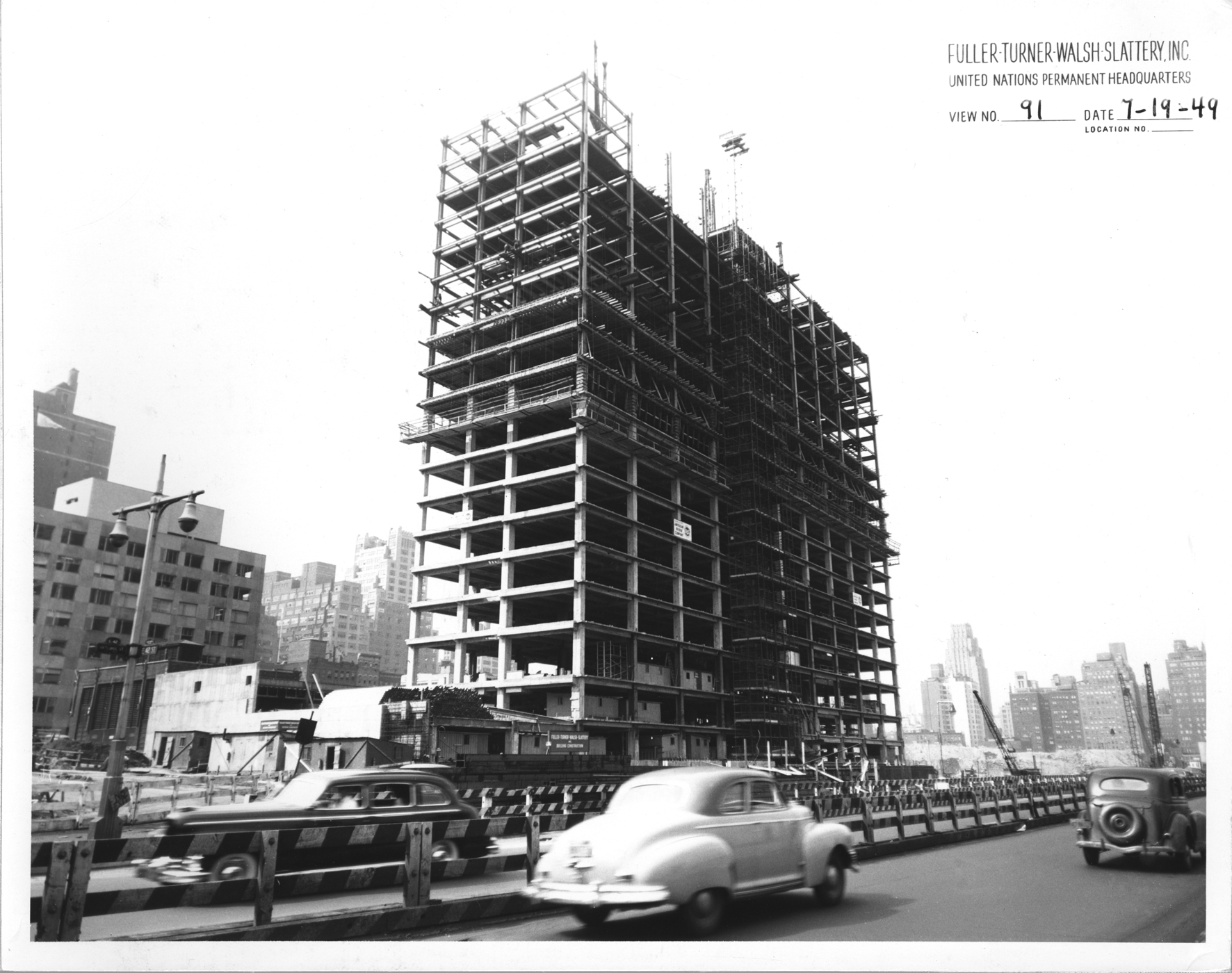

The Secretariat rises from the ruins of the slaughterhouses and breweries previously on the site. The chimneys of the then Consolidated Edison’s power-plant are in the background. Photo by J. Alex Langley

Secretariat Building under construction. Photos by J. Alex Langley

Secretariat towering over the dome of the General Assembly, 1951.

Le Corbusier envisioned a façade with sun-shielding slats of concrete or stone, like the ones he was using for a housing project in Marseille. Harrison wanted to use a new product called Thermopane, a form of tinted insulating glass. It was much more expensive but better suited to New York’s weather. Thermopane was selected after an in-house test confirmed that it was indeed preferable. UN Photo

Secretariat Post-renovation

In addition to the original occupants, the leadership of every UN office and liaison office in New York moved to the Secretariat after the renovation. UN Photo/Paulo Filgueiras

Secretariat Lobby, 1951.

Black-and-white terrazzo floor; brushed steel and green marble on the walls; low ceiling.

In those days, more areas of UNHQ were accessible to the public, including the Secretariat Lobby. UN Photo/MB

Secretariat: Entrance reserved for dignitaries- Post-renovation.

The curtain wall was replaced during the renovation. The new one is indistinguishable from the original but it performs better in terms of energy efficiency and blast protection. Image Courtesy of HLW International. Photo by Chris Cooper

Conference Building

Construction: 1950-July 1951

4 stories

Renovation: 2010 - April 2013

Tucked behind the Secretariat and connected to the General Assembly Building, the Conference Building overhangs the FDR Drive along the East River. Because of its location, the building is difficult to secure. Hence, the renovation required extensive structural enhancements, including moving several meeting rooms away from the overhang. A new, large lounge with river views - a gift from Qatar- replaces them.

The interior decoration reflects a strong regional component as Member States designed and furnished several spaces, thus leaving their architectural marks within the Conference Building.

The Conference Building houses three main Chambers - Security Council, Economic and Social Council, and Trusteeship Council - and six conference rooms.

Conference Building

The North Delegates’ Lounge before the 2010 renovation. UN Photo

The North Delegates’ Lounge in its original incarnation. UN Photo

The three-stemmed floor lamp is one of the original lighting fixtures in the Conference Building. It is shown here in the North Delegates’ Lounge. The lamp is often placed next to curvilinear fixed seating, typical of mid-20th century design. Photo by Gary Rosenberg

Trusteeship Council Chamber, 1952.

A gift from Denmark, the room was conceived by Danish architect and furniture designer Finn Juhl. The Trusteeship Council’s mission was to promote self-government or independence of UN Trust Territories. The Council suspended operations in November 1994 when Palau gained independence. The Chamber is now used primarily by the General Assembly and its committees. Photo by Ezra Stoller/Esto

Trusteeship Council Chamber, 1977.

Theatre-style seating for the delegates was installed in 1977. (The room had already been remodeled in 1964 to accommodate the growing number of Member States.) All council chambers have huge windows but the curtains are always drawn as direct sunlight interferes with photos. Photo by Ezra Stoller/Esto

Trusteeship Council Chamber. Post-renovation.

The colorful boxes on the ceiling accommodate light and ventilation and symbolize flags. The statue on the wall, entitled Mankind and Hope, is by Danish sculptor Henrik Starcke. Photo by Esther Nisanova

Security Council Chamber under construction. Photo by Hugh A. McKevitt

Security Council Chamber, mid-1950s.

A gift from Norway, the room was designed by the Norwegian architect Arnstein Arneberg.

The backdrop is a mural by Per Krohg, Norway. The mural blocks the view over the East River because it is placed in front of a huge window. By sealing the chamber, Arneberg underlined the Security Council’s independence vis-à-vis the outside world. In so doing, he eliminated the glare that makes it difficult to videotape the meetings. UN Photo/GR

Security Council Chamber. Post-renovation.

The Security Council’s primary responsibility is to maintain international peace and security. Fifteen members are in the Security Council: five permanent members (China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States) and ten non-permanent members elected for a two-year term by the General Assembly. The President of the Security Council rotates every month. Photo by Gary Rosenberg

Economic and Social Council Chamber (ECOSOC). Post-renovation.

Markelius dropped the white false ceiling in the delegates area but left it unfinished, and black, in the area open to the public to symbolize the work of the Council – forever ongoing, never finished. Photo by Esther Nisanova

Economic and Social Council Chamber (ECOSOC), 1952.

A gift from Sweden, the room was designed by Swedish architect Sven Markelius, who was also a member of the UNHQ Board of Design. This council was established as the primary organ to coordinate programs in economic and social development. Photo by Ezra Stoller/Esto

Economic and Social Council Chamber (ECOSOC). Post-renovation

Sweden donated a new monumental curtain, Dialogos, by Swedish designer Ann Edholm. The podium is now glass-enclosed and the beige and turquoise chairs, here and in all meeting rooms, are upholstered in Naugahyde, a plastic substitute for leather. UN Photo/Mildred Ochoa

General Assembly Building

Construction: 1951-October 1952

4 stories

Renovation: 2013 – September 2014

58 Member States at the completion of UNHQ

193 Member States in 2015

In the original design, the General Assembly Building houses two halls standing back to back and no dome. The design included a smaller hall to the south and a larger one to the north. This configuration explains the building’s peculiar shape. Because of financial cutbacks, only one auditorium was built. It was much larger than planned and located in the middle, where the building is narrowest and lowest.

The dome was added upon the suggestion of Vermont’s former Senator Warren Austin, the Permanent Representative of the United States to the United Nations, in order to persuade Congress to provide the United States’ share of the project costs.

In addition to the General Assembly Hall, the building houses eight conference rooms, three of which were built as part of the renovation.

The building also houses the Visitors’ Lobby, the only area of UNHQ accessible to the public through a new screening structure built as part of the renovation.

General Assembly Building

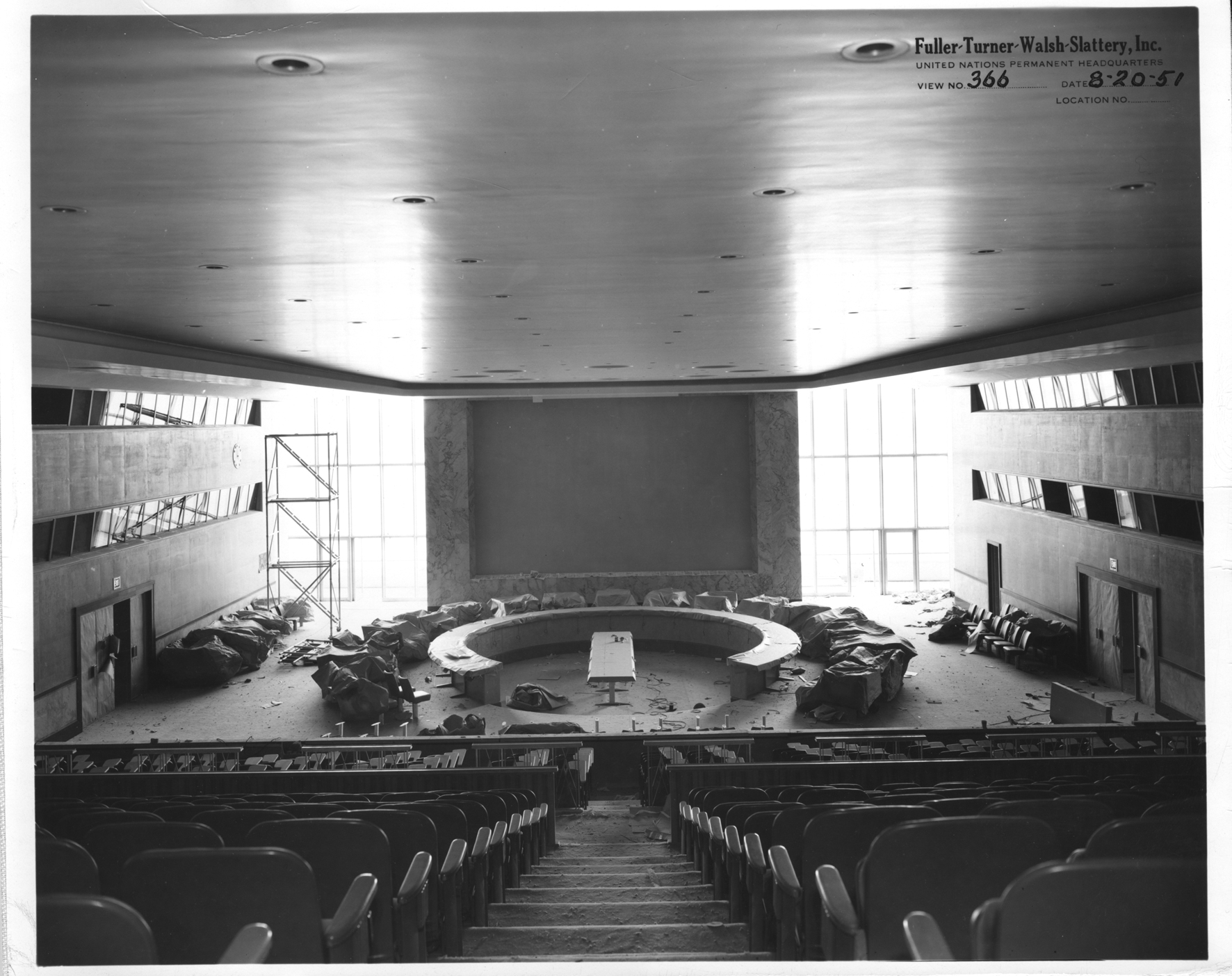

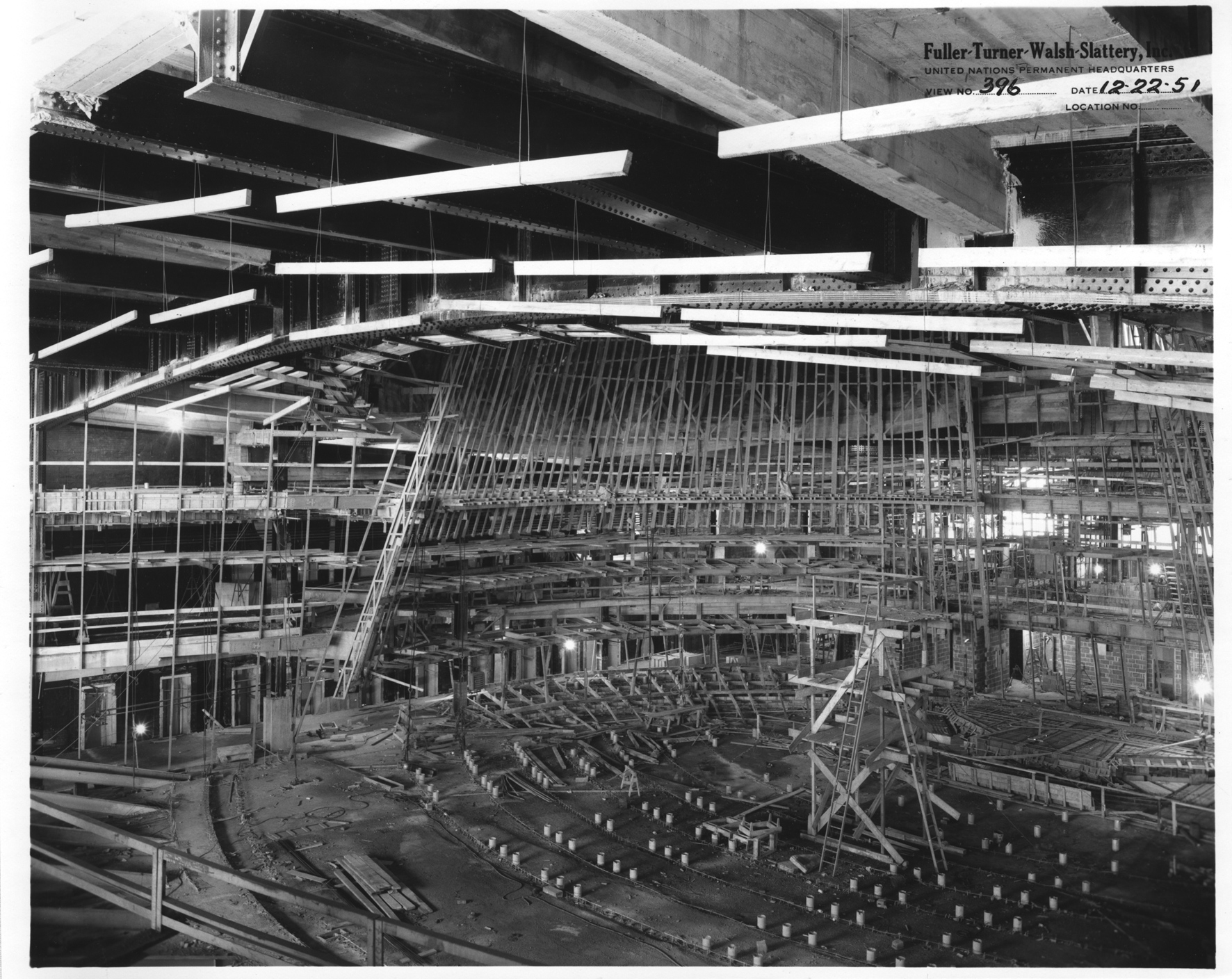

The General Assembly Building under construction. Photo by Hugh A. McKevitt

The General Assembly Building under construction. Photo by Hugh A. McKevitt

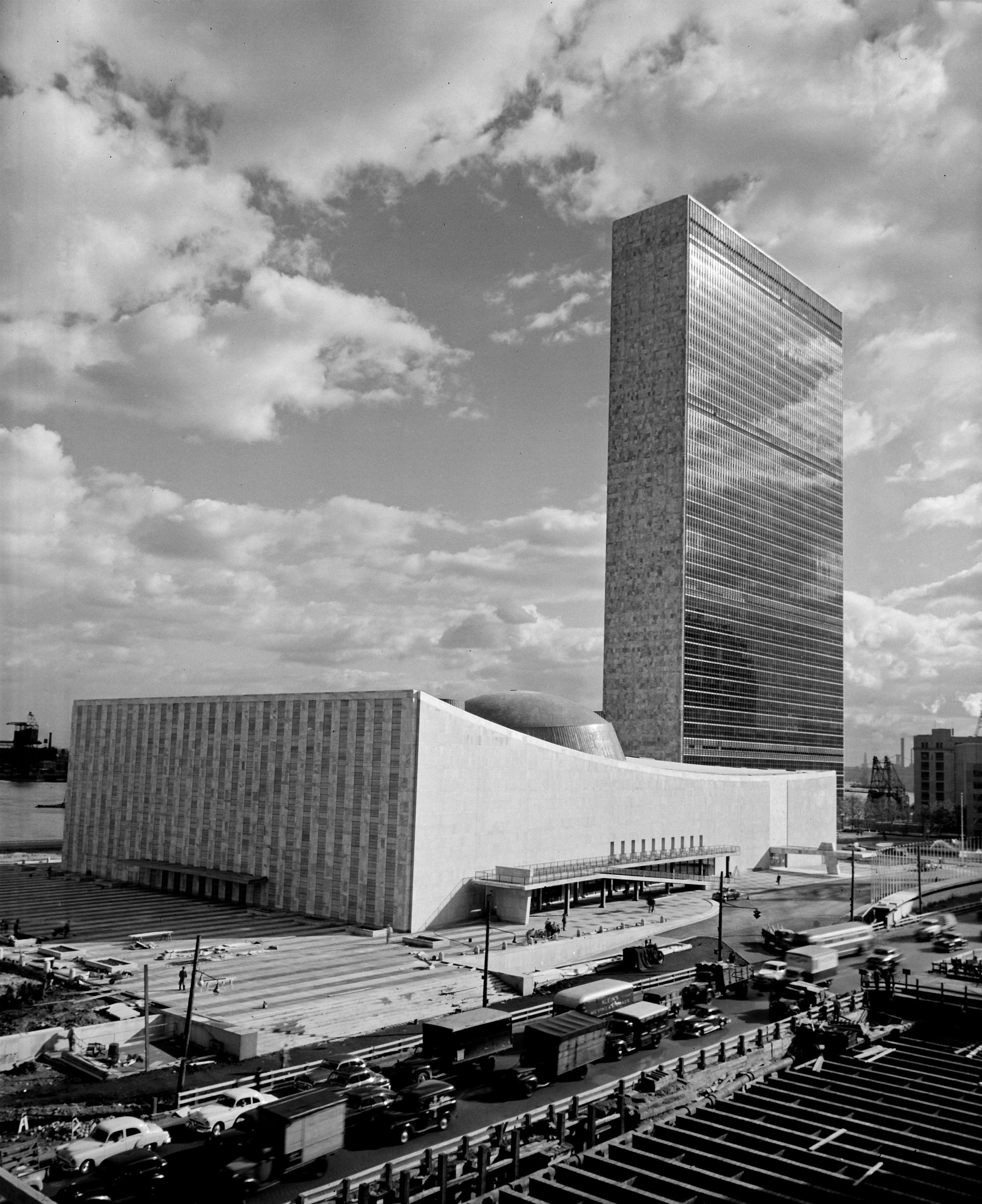

General Assembly Building after completion in 1952. View from First Avenue.

The sculptural form of the General Assembly’s curved roof and walls was an unexpected departure from the dominant rectilinear aesthetic of the International Style. The curve is indeed the building’s distinctive feature outside and inside (the Assembly Hall is completely non rectilinear, including the juncture of wall and floor). The two-level ramp is an emergency exit. UN Photo

South façade of the General Assembly Building. Post-renovation

In contrast to the curving east and west walls and roof, the south side is a huge plate-glass window, 53 ½ feet (16 m) high, set in a deeply recessed marble frame through which the delegates’ entrance and lobby are visible. The all-glass façade, turned toward the Secretariat and the Library, shares their architectural language of bold geometry and transparency.

Photo by Gary Rosenberg

Sloping backdrop of the General Assembly Hall

Its original ornamental grid of disc-shaped lights was removed because television crews and photographers were unable to capture high-quality images of the speakers. UN Photo

General Assembly Hall. Post-renovation

The General Assembly Hall re-opened in September 2014 to host the annual General Debate.

Member States are equally represented in the main deliberative body of the United Nations: one member, one vote. Interpreters translating into one of the six official languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish), verbatim reporters, television cameramen, and photographers occupy glass-fronted booths that overlook the space. The number of delegates per Member State was reduced over the years to accommodate the growing membership. Now, each Member State has six seats: three for full delegates (beige chairs) and three for alternates (turquoise chairs). The abstract murals on either side are an anonymous gift. Originally designed by Fernand Léger, they were painted by Bruce Gregory, one of his pupils. UN Photo/Mildred Ochoa

Scaffolding in the General Assembly Hall. During renovation. UN Photo/Werner Schmidt

General Assembly Building: North façade and visitors’ terrace, 1952

Vermont marble. The window panels are progressively smaller toward the top to make the façade appear taller. (Inside, the Lobby appears longer than it is because of a slight incline up in the floor and down in the ceiling toward the south end of the space.) UN Photo/MB

United Nations Headquarters. Post-renovation

The Library Building, in the background, was built some ten years after the complex’s three original buildings. It was dedicated in 1961 to the memory of Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations, who died in a plane crash in the Congo, Africa, that same year. The future of the Library is uncertain. UN Photo/Werner Schmidt

Visitors’ Lobby of the General Assembly Building, 1952. North side

In the entrance, cantilevered, rounded balconies and a sweeping ramp leading to the General Assembly Hall contrast sharply with the high walls and exposed ventilation pipes in the ceiling. UN Photo

Everything will be alright when people stop thinking of the United Nations as a weird Picasso abstraction and see it as a drawing they made themselves." - Dag Hammarskjöld

Sources

United Nations, The Story behind the Headquarters of the World, Max Ström, 2015. Text by Mark Isitt. Photography by Åke E:son Lindman. Detailed bibliography.

The United Nations at 70, Restoration and Renewal, Rizzoli International, 2015. Foreword by Ban Ki-moon. Essays by Martti Ahtisaari and Carter Wiseman. Various photographers.

The U.N. Building, Thames & Hudson, 2005. Foreword by Kofi Annan. Essay by Aaron Betsky. Photography by Ben Murphy.

The United Nations, Princeton Architectural Press, 1999. Photographs by Ezra Stoller. Introduction by Jane C. Loeffler.

A Workshop for Peace, Designing the United Nations Headquarters, The Architectural History Foundation and MIT Press, 1994. Text by George A. Dudley.

This exhibit was launched in May 2025