September 2015, Nos. 1 & 2 Vol. LII, The United Nations at 70

My United Nations memories reach very far back; as a young diplomat, I attended the first session of the General Assembly, in London, in 1946. It was a time of immense hope which was soon dashed. Before the end of the decade the permanent members of the Security Council were in open competition both ideologically and geopolitically. The collegiality between them, on which rested the collective security system, disappeared. A new world war with major powers in direct confrontation was averted, but otherwise, for decades, the ability of the United Nations to carry out its primary purpose, the maintenance of international peace and security, was severely constrained.

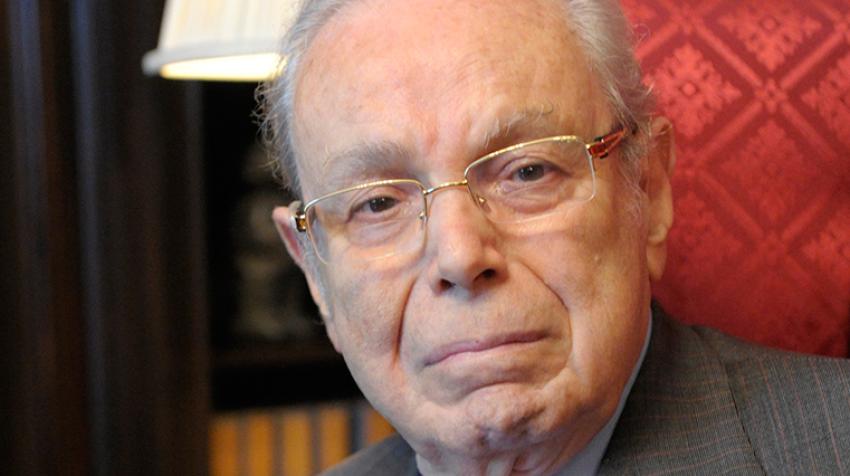

My career as a diplomat took me elsewhere for almost a quarter of a century before I returned to the United Nations first as the Ambassador of Peru, then as a senior Secretariat official, and, a decade later, as Secretary-General. The threat of nuclear war had receded from its October 1962 peak, but most of the other aspects of the cold war lingered. The United Nations and its Secretary-General remained largely marginalized. I am proud of what was accomplished in the decade that I held that position, much of it through careful, painstaking United Nations good offices, frequently with the assistance of outside actors, but often also by the United Nations lending assistance to the efforts of others, working closely and effectively with the Security Council.

It was a time of renewed hope, as the Security Council noted, meeting for the first time at its first ever summit of Heads of State and Government, one month after my departure. The United Nations had played a key role—frequently the central one—in ending a series of conflicts in Afghanistan, between Iran and Iraq, and in Cambodia. Agreements on Angola opened the door to the self-determination and independence of Namibia and helped to end apartheid in South Africa. In Mozambique peace was near. The violence in Nicaragua ended, and, in El Salvador, the first United Nations mediation of an internal conflict was successfully completed. What the United Nations did in the late 1980s and early 1990s contributed significantly to the long process of unwinding the cold war.

What lessons do I draw for the future of the United Nations from that time? I devoted considerable effort to my 10 annual reports, each of which was a months-long effort involving my closest colleagues for sessions that spoiled many a summer. I have published a book of memoirs. I have had 23 years to reflect further on this question, but rather than writing a long list of prescriptions, I prefer to distill from the many experiences a single, fundamental lesson.

It is customary to point to Article 99 of the Charter of the United Nations as the most important advance of the United Nations with respect to the Covenant of the League of Nations, the only treaty prior to the Charter that attempted to put in place rules and mechanisms for the maintenance of international peace and security for an organization that aspired to universality. The importance of the principal operative provision of Article 99, the power of the Secretary-General to bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security, is beyond question, but it has been overestimated to the extent that the Secretary-General has only invoked it half a dozen times. Article 99 is more important, in my view, in what it implies and presupposes by specifically encouraging the Secretary-General to use his judgement as to whether a matter should be brought to the attention of the Security Council as it could potentially threaten the maintenance of international peace and security. This core article mandates that the Secretary-General should be constantly monitoring situations that might fall under this category. How else can he exercise the judgement requested of him? Similarly, the article presupposes that he will have the means to do so. The fact that Member States have fallen far short of providing him such means is a severe handicap, but it does not undermine the conceptual underpinning that these elements provide for the good offices of the Secretary-General.

Somewhat less consideration has been given to another Article in the Secretariat section of the Charter. That is Article 100, whose importance I wish to highlight.

When I attempt to distill my experience to its most precious essence, I come up with a single word: independence. That word encapsulates what gave me the strength and the ability to make a positive difference regarding a number of seemingly intractable issues that had bedeviled the international community, defying solution for years and years. Independence has consistently been my one-word answer to the question, how did you do it?

The word independence does not appear in Article 100. Under its second paragraph “Each Member of the United Nations undertakes to respect the exclusively international character of the responsibilities of the Secretary-General and the staff and not to seek to influence them in the discharge of their responsibilities.” The word “independence” might have been a bridge too far in the 1940s, at a time when sovereignty was still significantly more robust in substance and in the minds of statesmen than it is today. But it was unnecessary: there can be no doubt from the context that that is what the Charter enshrines. That is certainly as I saw it. At the time, and all the more so in retrospect, it was invaluable to me. I shall briefly explain why this was so.

Like Hammarskjöld, I did not seek to be Secretary-General. My Government wished me to be a candidate and informed Security Council members that I was available, but I refused to campaign. I did not ask for anyone’s support. I did not go to New York. I made no commitments to Member States or anyone else to become Secretary-General; there was no quid pro quo, no do ut des. I thus came to office having promised no one anything. Nor did I have any desire to remain as Secretary-General beyond the five-year term to which I was appointed.

On 13 May 1986, a few months before the expiry of what turned out to be my first term as Secretary-General, I delivered the Cyril Foster Lecture in the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford University. Twenty-five years before Dag Hammarskjöld delivered a similar lecture on the subject of “The International Civil Servant in Law and in Fact”. My subject was The Role of the Secretary-General.

I reviewed the good offices role of the Secretary-General and summarized it in one word—impartiality. “Impartiality,” I said, “is the heart and soul of the office of the Secretary-General.” I took it one step further, suggesting that in order to ensure the impartiality of the Secretary-General, the healthy convention that no person should ever be a candidate for the position should be re-established. It should come unsought to a qualified person. However impeccable a person’s integrity may be, he cannot in fact retain the necessary independence if he proclaims his candidacy and conducts a kind of election campaign.

Independence does not mean that the Secretary-General can or should act as a totally free spirit: the Secretary-General is bound by the Charter of the United Nations, and for the United Nations to be an effective agent for peace he must work in partnership with the Security Council. But that partnership is strengthened if he takes a perspective broader than that of individual Member States or even the selection of them embodied in the Council. There are instances in which he may feel compelled to distance himself slightly so as to keep channels open to those who feel misunderstood or alienated by it. The maintenance of this discrete position will make him a more effective and credible partner. If he is clear about this with Security Council members they will see the usefulness of his doing so and respect him for it.

Undeterred by my clear public stance, which they could not unfairly have interpreted as an assertion of independence, the five permanent members of Security Council approached me jointly—something they did not have the habit of doing—at the beginning of October 1986 with the request that I accept another term. I agreed only with reluctance, but I began my second term feeling newly empowered. The list of instances in which my independence with respect to Member States opened opportunities that would not have appeared had I confined myself to echoing the Council’s every utterance is too long to recite. I believe it catalysed the change in the position of the Security Council with respect to the Iran-Iraq war that provided a framework for solving it. I have no doubt that it made it possible to successfully bring about a comprehensive rather than a partial peace in El Salvador or no peace at all. These are merely two cases in which my independence provided me with the freedom of action necessary to discharge my responsibilities in a manner that was responsive to the wishes of the membership as a whole. That is the value of not having been a candidate.

Is this lesson still relevant? That is for Member States as a whole, and particularly for the members of the Security Council, to decide.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.