© COP28/Christopher Pike | The COP28 President and other participants onstage during the Closing Plenary at the UN Climate Change Conference COP28 at Expo City Dubai on 13 December 2023.

By: Bitsat Yohannes-Kassahun

This year’s Conference of Parties (COP) marked its twenty-eighth year. As with other years, COP28, which just concluded in Dubai, UAE, had moments of intense negotiation, reflection, and innovation. It also has the usual mixed bag of various pledges and, at times, self-congratulatory announcements where different entities got to show their contributions to making the planet a green haven, as well as the many others lamenting how inaction and greenwashing[1] will be the death of us all.

Word smithing also seems to be the order of the day, where "phase out", "phase down", and "reduce" fossil fuels, were heatedly debated even as the conference was winding down on 12 December.

Aside from the many controversies at COP28, it was also when global leaders came together to agree on a way forward on the technical findings of a Global Stock take (GST) process that began at COP26 in 2021. The GST assesses the collective progress towards the Paris Agreement, the legally binding international treaty on climate change signed by 193 countries in December 2015, at COP21. Under Article 14 of the Agreement, countries, are to do the stock take to assess climate action gaps and agree on how to move forward on limiting "the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels." Scientists warn that exceeding this limit would cause increasingly devastating and irreversible impacts of climate change, including extreme weather patterns, flooding, heatwaves, and droughts, to name a few.

Unfortunately, the world reached this dangerous milestone on 17 November 2023, when global surface air temperature reached 2.07°C above the pre-industrial average. Current estimations will see temperature increases of 2.7 degrees above industrial levels, leading to dangerous impacts of climate change on the daily lives of communities around the world, particularly in vulnerable countries with less adaptation capacity, including African countries.

While this is one indicator out of many, it points to a precarious situation where humanity is heading towards an unlivable planet. The World Meteorological Organization noted that the past 8 years were the warmest ever registered, with record-breaking extreme weather events occurring on every continent in 2022.

Unsurprisingly, the main technical conclusions of this first-ever GST are mainly:

- The world is not cutting emissions fast enough,

- Countries are not prepared to face the impending climate hazards

- And poorer countries are not getting support from the richer countries, who are mostly responsible for the climate mess to begin with.

It is a glaring reminder of how far behind we are, collectively, in doing what needs to be done to course-correct from this dangerous trajectory. The main solutions for course correction being negotiated at COP 28 include a decision on fossil fuel usage, tripling renewable energy production by 2030, and increasing climate financing amounts to unprecedented amounts, into the "trillions." While this is the bigger global picture, Africa’s stock take paints an even grimmer picture.

The impact of climate change on Africa is a lived reality

Africa is disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate and the most-exposed region to its adverse effect. The mean temperatures across the continent are increasing faster than the global average, and rainfall patterns, the continent’s lifeline to feeding itself, will increasingly be unpredictable in intensity and frequency. The impacts of a changing climate on Africa are already manifested in severe drought, flooding, desertification and changes to precipitation and crop output. Economically, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that for every two degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels, Africa loses approximately 5% of its GDP.

In 2023 alone, African countries experienced hazardous extreme weather conditions be it the devastating drought that is killing thousands in the greater Horn of Africa, Cyclone Freddy that battered Southern Africa displacing thousands, or the heavy flooding in Central and West Africa due to unpredictable rainy seasons, or Tropical Storm Daniel in North Africa that killed over 4200 people in Libya and displaced over 40,000 people. In addition to the devastating, direct, and immediate cost to human life, changing climate conditions such as heatwaves are increasing the incidence and risk of life-threatening infectious diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever.

A drastically changing climate also does not bode well for Africa’s infrastructure. For example, in January 2022, Tropical Storm Ana hit the southern African countries of Mozambique, Malawi, and Madagascar heavily. Due to the storm, Malawi Lost 30% of its Electricity (about 130 MW) when the storm destroyed the control mechanisms for the dam at the Kapichira Hydropower Station. Malawi estimated that the temporary rehabilitation of the damaged Kapichira Power Station would cost about $23 million, which is beyond the capacity of the country’s utility. Similarly, Tropical Storm Ana damaged 30 health centers, 23 water supply systems, and 144 power poles in Mozambique. Two months later, in March 2022, Tropical Cyclone Gombe affected 37 energy stations and caused power outages and communication breakdown, according to the Mozambican state power company, Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM), leaving hundreds of thousands of residents without electricity.

The dearth of climate and other financing for Africa puts the continent in a vulnerable position

The picture for project financing in Africa, whether it is for energy, other infrastructure, or climate adaptation is daunting. African countries have faced increasingly diminishing financing options in the last three years. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), international project financing deals declined by 47 per cent and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows to Africa, saw a 44 per cent decrease, from $81 billion in 2021 to just $45 billion in 2022.

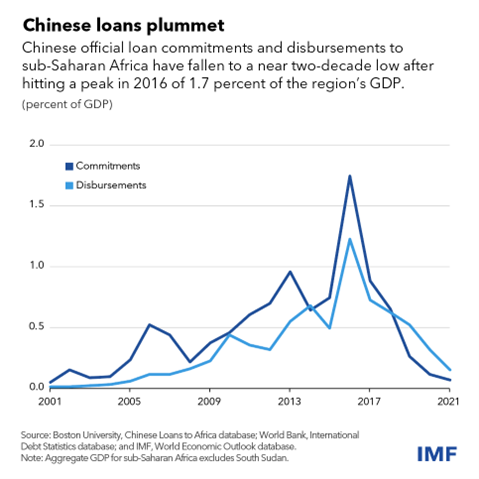

Moreover, financing from China, Africa's largest single-country trading partner and financier in the last 20 years, is rapidly declining. According to the International Monitory Fund, IMF, "The ripple effects of China's slowing economy extend to sovereign lending to sub-Saharan Africa, which fell below $1 billion last year — the lowest level in nearly two decades. The cutback marks a shift away from big-ticket infrastructure financing, as several African countries struggle with escalating public debt." (Figure 1)

With these financing trends, increased public indebtedness, and the increasing adverse impacts of climate change on the continent, it is no surprise that the top priority for African countries at COP28 revolved around climate financing, just energy transitions and operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund agreed upon at COP27 in Sharm-El-Sheik last year. However, the responses they are getting are best summarized by one author who observed that "the sums currently earmarked for climate finance – for mitigation, adaptation and now loss and damage – look like accounting errors compared to forecasts of the sustained investment levels needed to finance an international green energy transition."

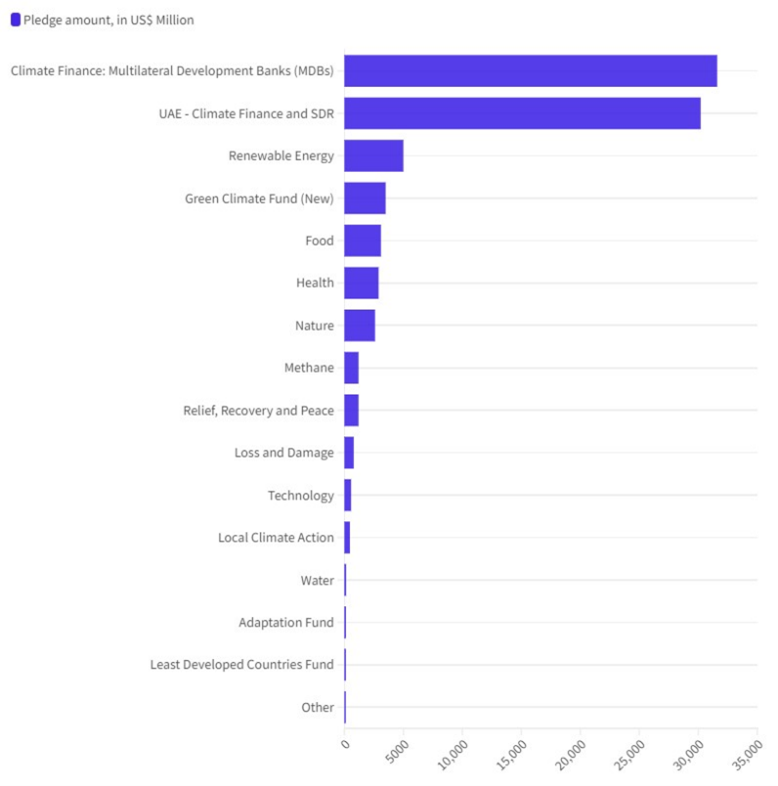

According to the International Energy Agency, IEA, achieving Africa's energy and climate goals will require over $190 billion per year from 2026 to 2030, with two-thirds going to clean energy. Given this picture, however, COP28 has had different pledges of about $83 billion as of 11 December 2023 (not exclusively allocated to Africa, underlining the gap). The major pledges were in the form of climate finance, with the UAE pledging about $30.2 billion, including a reallocation of its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) of $200 million, and the Multilateral Development Banks collectively pledging $31.6 billion. While these are the global numbers, African countries should not anticipate much from these pledges, especially since only 2 per cent of the renewable energy investments went to Africa in 2023, a worrisome but continuous trend from previous years.

Africa as an ideal canvas to build the model sustainable cities of tomorrow

With the lowest rate of access to electricity in the world, making up 80 per cent of the global population without access to electricity[2], and with sombre projections that state that only eight African countries will achieve universal electricity access by 2030 and that "some will take over 100 years to fully electrify," Africans should not be lulled by the misconception of "seed funding" or "leveraging" a few drops in the funding bucket that claim to magically solve the continent’s gargantuan challenges. According to some estimates, "less than 30 cents of private capital is unlocked by every $1 of public climate finance."

Moreover, while the annual Conference of Parties meetings are diplomatic opportunities to bring different people together, they should not be the main forums for Africans to negotiate for more. For example, the golden achievement of COP27, the Loss and Damage Fund which aims to "address the impacts on communities whose lives and livelihoods have been ruined by the very worst impacts of climate change" was yet again billed as a success at COP28 despite the fact that the $792 million pledged would only cover 0.2 per cent of the estimated $400 billion per year needed for loss and damages. Moreover, its operationalization is fraught with disagreements about the source, the scope and even the wording of the fund. Similarly, one of the crowning achievements of COP26, the Just Energy Transition Plan for South Africa, has yet to disburse the promised $8.5 billion to jump-start the country's transition from coal.

Instead of pushing the continent to "be more ambitious" with its climate pledges, relaying on mere drops of financing, here is a novel idea. If there are proven, sustainable, financially, and technically sound solutions to avert the climate crisis, make Africa a proof of concept to show the rest of the world that these solutions work. With so much to lose and so far to go, Africa is an almost blank canvas to build the model cities of tomorrow, powered by renewable energy-based public transport, energy-efficient buildings, smart grids and electrification, industrial development, and secure food systems. Because just like every other country is looking out for their best interests and the optimal quality of life, there should be no reason why Africans are expected to settle for anything less.

Notes:

[1] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “greenwashing” as “the act or practice of making a product, policy, activity, etc. appear to be more environmentally friendly or less environmentally damaging than it really is”

[2] International Energy Agency (IEA), 2022. Africa Energy Outlook, p.37