“Genocide is a human creation so there has to be a human solution to it. What the world hasn't learned is what to do about the response….The early warning is there [...] but response is extremely poor. For ‘never again’ to work, we need to invest energy in addressing the foundations that produce the people who end up becoming genociders.”

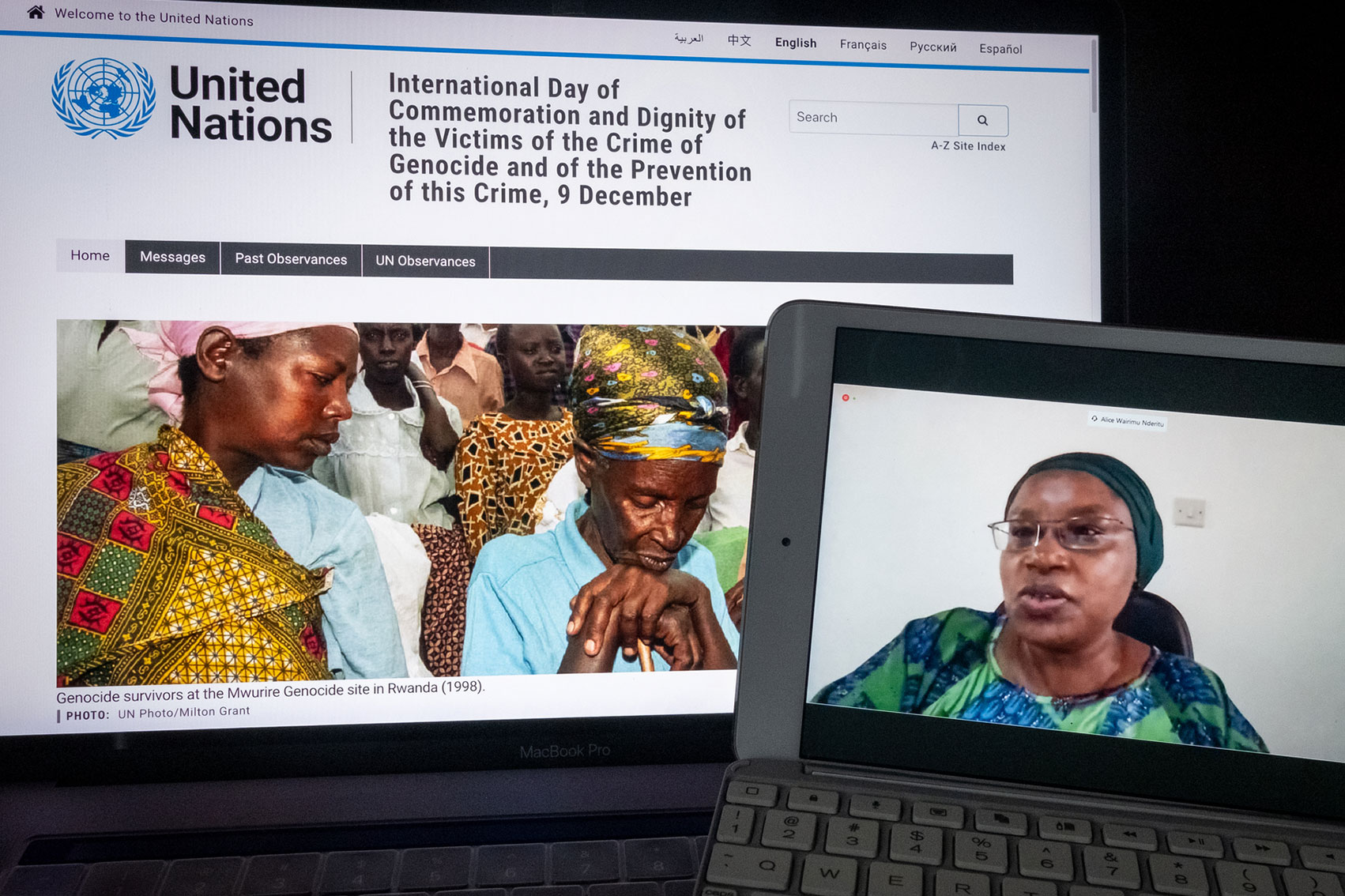

Alice Nderitu, the Secretary General’s Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, speaks candidly about her experiences mediating in areas of conflict and how her powerful storytelling techniques built a peace agreement between 56 ethnic communities that still stands today. She also shares the indicators that can lead to violence and the importance of being an active listener.

As she describes: “I always say that, as a mediator, you have to have a very small mouth, big eyes, and big ears because you have to keep listening. Especially listen to what is not being said.”

Full Transcript +

Melissa Fleming 0:00

From the United Nations, I'm Melissa Fleming. This is awake at night. Today, my guest is Alice Nderitu who is the Secretary General's Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide. Alice, today you are speaking to me here in New York, where you are based and you're originally from Kenya. Your work focuses on reconciliation and the prevention of conflict. I wonder how much of your upbringing in Kenya prepared you for this path?

Alice Nderitu 00:50

Not much. I never grew up thinking that this was what I was going to do. I never grew up in conflict. But when I left the university, then I went to work for the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights. And then I travelled around the country and I became so surprised by the difference between the conditions of the life I knew in Nairobi and in the schools and being in the life that people were living - a lot of conflict, quite a lot of violence, quite a lot of unsolved issues.

At that time, I was teaching human rights. I was teaching at UN conventions. It got to a point where I kept getting asked by people on the ground, ‘Thank you very much for this information, how do we apply that in our daily lives?’ And it troubled me because, at that time, we had a very repressive government, and our Constitution had nothing on human rights in it. I would be imagining that they are thinking, ‘So what? Thank you so much for that information. So what?’ They would say things to me like, ‘Okay, so you taught us about our rights. You said that when the police come here, they shouldn't brutalise us. But the police came and did the exact thing you said they shouldn’t do. We had the information, we had the knowledge, but there was nothing we could do’.

So then it began to worry me in terms of what else can I do next? It just came by chance, because one of my colleagues was taking an online course linking human rights and conflict prevention. And my colleague was very behind in his studies and our boss was really angry at him. So then my colleague said, ‘I can't do this thing. I’m beat, I can't do it.’ Then I said, ‘Okay, let me do it for you.’ And it completely opened my eyes in terms of there is actually a link between human rights and conflict prevention. And so from conflict prevention, then I would then move to other spaces of prevention of genocide. Because, after working in Kenya, then I started working in other countries. I worked in Ethiopia. I worked in Zimbabwe. I worked in Sudan. And then I worked in Nigeria, quite extensively, I worked in South Sudan.

And in all these places, there were so many places in which communities were quite alone. There was so much violence going on; inter-ethnic violence, inter-religious violence. They didn't know what to do. I would go to the villages, and people will tell me, ‘On this day, we learned that we were going to be attacked. On this day, we learned that this was going to happen to us.’ ‘On this day, this and this and this, and then it happened.’ The question then became for me, ‘If people know that they are going to be attacked, and you don't have 911. You don't have ways of calling. The nearest policeman is 600 miles away. What do you do?’

That then became the next part of my question, I need to find an answer for these people who keep saying, ‘We know the violence is coming, but we don't know who to tell.’ Unfortunately, it keeps troubling me even now, there are still quite a number of places in the world where people know for sure that violence is coming and they do not know what to tell. Sometimes they know who to tell. But then no action is taken. It's been a long road to where I am right now. I feel that I have almost like a jigsaw puzzle that you keep pushing this to fit. And then as soon as you think it's about to fit, you feel you have to fit in something else. It's so incomplete this jigsaw puzzle that I have to keep thinking, ‘What next? How do I ensure that if people know that violence is going to happen to them, that then that violence is stopped?’

Melissa Fleming 04:47

That's really interesting. We'll get into that in more depth - how you went from theory to giving people agency. But before that, just you said you had a peaceful childhood where you knew no violence and just tell me about it. What was it like, you grew up in Nairobi?

Alice Nderitu 05:03

I grew up in Nairobi, but also we had a very interesting half-life because my father worked in Nairobi, and he wanted to see his children, so during the school holidays, we would come to Nairobi. But we were in the village. Growing up in the village, we had traditional systems. And those traditional systems involved elders, and the elders were usually men. They would then sit under a tree, and then you would come along and say, ‘My cow is lost and the one at my neighbor's looks like my cow and the two of them would be there and they would be making their cases about the ownership of the cow. And then the elders would make a decision.

I got fascinated with that because my grandmother could read and write. So they often called her when there was something to be read and written. But also, I had a very cheeky brother, he used to entertain himself by climbing the tree and then listening to what the elders were saying. I actually remember it was on my eighth birthday when my brother told me, ‘I'm going to give you a birthday present, and never tell anyone. Promise you’ll never tell anyone.’ I said, ‘I won’t.’ So we went up the tree and it was amazing to watch the humility of people who we knew were strong out there; our teachers, for example. When they had a case, to be adjudicated by the elders, how they would come there, and you would see how humble they were.

I became very, very fascinated with that whole aspect of these elders who can make such decisions. And at the end when they made the decision, one of them would hit the ground with a staff and say, ‘Decision has been made.’ And I would tell my brother, you know, ‘I'm going to be an elder, and I'm going to sit there and I'll make decisions.’ And my brother would tell me, ‘You’re a girl. Girls don't get to do that. Only men can do that.’ And so we...now it's a joke between us, we always remember that. And he reminds me, and I remind him too that he said that women can't do that kind of thing. And yet I've done it in so many spaces, in so many spaces. So I learned that most people say that, ‘Oh, you can't have women sitting in those kinds of spaces’. But what I have learned, I've learned over and over again, is that as soon as I show up in a place where there is violence, first of all, you can see they're so sceptical, they're all looking at me, like, ‘Really?’

Melissa Fleming 07:32

Because you're a woman?

Alice Nderitu 07:34

Yes, because I'm a woman. So I let them talk but what they don't know is that before I show up anywhere, I have read anything I can get hold of. I have watched anything I can get hold of about a particular conflict. I have spoken to so many people. I have done my research. As soon as I begin to speak, then I see their faces. I see their respect. I see that they now understand that I can provide solutions. Because once the community realises that you have solutions, that you have the skills to solve their problems, then it doesn't matter whether you're a woman or a man.

Melissa Fleming 08:10

Can you give me an example, maybe paint the picture of a time when you entered a community that was anticipating conflict or had conflict, and you played this role? What was it like and what was the situation?

Alice Nderitu 08:25

In Nigeria, I think Nigeria was my most challenging. At the same time, that's where I got the most results. I went to this place called Southern plateau. And we had 56 ethnic communities, 56! I held this mediation in a football stadium and it took more than a year. Very colourful, some people would come on their horses, and you know, that kind of thing. And it's a very intense process where there are so many issues that people are fighting over; grazing, especially grazing land. They're fighting over ethnic stereotypes and prejudices, you know, all these kinds of things. Then there's the deep religious mistrust between Christians and Muslims.

So we'd be sitting there and we'd be interrupted by so many people surrounding us, just coming to marvel that there is a woman coming here to solve these issues. There was no disrespect at all. I've been disrespected in my own country in Kenya. But in Nigeria, there was no disrespect. But there was always that sense of somebody trying to ask that question. There's always pushing, you know, trying to see how much you know, and trying to ask, ‘So and so came here and tried to solve this and they couldn't do it. What makes you think you can do it?’ asked in a respectful way, but asked anyway.

And so at the end of the day, by the time you go to bed, you're so exhausted. It's so exhausting because when you are mediating, you spend the whole day observing the people in the room - who is talking to who? Who is not talking to who? Who is speaking about what? Who is getting agitated when this person is speaking? You have to always be...you know, you have to keep looking out.

I always say that, as a mediator, you have to have a very small mouth, big eyes, and big ears because you have to keep listening. Especially listen to what is not being said. What happened to me though, was that my dressing changed. I got to a point where I decided that despite my being a strong feminist, that in those kinds of spaces, I want people to remember what I say, not what I wore. So I started blending in. I started dressing the way people were dressed. So that's how I started wearing these long dresses. I started putting a headscarf on my head. I didn't want people to ask me questions in the middle of a very, very intricate discussion on land use and at what point whose cows should go and drink from the river? Then somebody just says ‘So do people in your home? Do they mind that you don't cover your hair?’ You know, like, that kind of thing completely distracts everyone and everyone now is focused on your hair. So then I decided ‘No, I need to adapt.’ So that's what I did.

Melissa Fleming 11:13

So I'm just trying to picture the scene, you're in a football stadium, like a soccer stadium. And so you're sitting in the field? Just describe the scene and if you're trying to resolve just one of those, perhaps, land use issues? How many people would be sitting around with you? And was it only men? Or were there also women involved? How would you kind of start off the meeting?

Alice Nderitu 11:42

The first thing that I do when I get on the ground is find advisors from the local communities. Advisors who are respected by the communities because they also have to see themselves in the process. So it's not just this foreigner sitting there who will make decisions and go. We speak with the Chiefs. There’s a lot of planning before you begin the dialogue process. People think the dialogue process is the real work. The real work is the plan of how to even get it started.

In Nigeria, for example, they have traditional leaders, and then they have the government leaders. So you have to see all of them. You ask the chief, you say you need an advisor. So the Chiefs would usually give advisors who are professors. They're professionals in their community. And usually what happens is that they give you men. Then you have to devise a way to bring in women. So in terms of the communities themselves, you know, we have people who are actually entrepreneurs in peacebuilding. They've been in so many peace meetings, they know how to say the same things over and over again, to the extent that you can be in a meeting and you leave feeling that it was very fruitful. But it wasn't.

I kept telling my teams that we cannot be meeting with the same elders. We need to get fresh people. But we need to get fresh before with gravitas, which is difficult because they need to be heard when they go back to the community. People need to listen to them. So we eventually came up with a list of six people. We would ask the chief to give us a religious leader, to give us a cultural leader, to give us a leader from the business community, to give us a youth, to give us a woman and finally, we had a category we called a ‘respected opinion leader’’. Each of the 56 ethnic communities has sent these six people.

So we are sitting in this football stadium and we arrange the ethnic communities alphabetically. Because if you don't do that when it's time to speak… On one occasion, actually, in South Sudan, people began fighting in the peace process itself. So I'm sitting here in the middle and then the advisors are sitting next to me. What happens is that we ask you, you as your ethnic community, to go and write down an answer four questions. And the four questions are, ‘Who is fighting? Whoever is fighting who, are you part of it? Okay, then if you're part of it, what's the timeline of that conflict? How long back does it go? Who are the key actors in this conflict? And then finally, ‘What are your recommendations?’

So then they would come back, and then we would have this whole session where each ethnic community would stand up and talk about what they had put together. And that's always the most difficult thing to manage. As soon as they read, then the other ethnic communities want to respond. They want to say ‘That's not true. That's not true.’ So I have to find so many ways of cooling temperatures so that everybody's heard. So then after they finish, my method is through storytelling, because in many African traditions, grandmothers are storytellers. They derive a lot of power from that because you can tell a story and say a very painful thing that can be taken lightly. But if you say directly, then it's very, very, it's difficult to say directly. So I have stories for everything and I keep my stories very short.

Melissa Fleming 15:14

Do you have an example maybe from this stadium of a story you told?

Alice Nderitu 15:!8

There was one ethnic community that kept... When we were in public, they were very good and very nice and saying all the right things. But behind the scenes, they were doing all these terrible things. I told them, ‘You probably know the story about the scorpion that wanted to cross the river? He couldn't cross the river because, I mean, scorpions don't know how to swim. So then the scorpion saw a frog and says, ‘Please, Mr. Frog, will you help me to cross the river?’ And the frog says, ‘No, I can't’. And the scorpion said, ‘Why?’ He says, ‘I know you, you’ll sting me’ and the scorpion says, ‘But why would I sting you? I need to get across the river. Please help me’. So then the frog says, ‘Okay, hop on my back. Let's go.’

So then they went. The frog was swimming, swimming and then, right in the middle of the river, the scorpion stung the frog. As they both sank, the frog asked, ‘Why? Why? Why did you do this?’ And then the scorpion said, ‘Because that's my nature. I'm a scorpion’. So I asked that ethnic community ‘Have you gotten to a point in this violence, where you are now a scorpion? That despite the fact that you know that your children are so damaged by growing up in this space, despite the fact that you know that your children have not been to school for so long. You can't even go to the nearest market, because of the violence. Yet, over and over again, you keep doing the things we say at this table that you shouldn't do.

So are you the Scorpion? And if you are the scorpion, what should we do? What does that mean that you cannot move out of this phase of violence that others have moved? And we have to keep stopping the others from revenging? What does it mean that you are now the scorpion?’ Instead of me saying, ‘Why are you killing the others?’ The scorpion analogy gives them a better way to discuss the issue. They say ‘No, no, no, we are not the scorpion’. And the others are saying ‘No, no, no, you're the scorpion’. So then the whole discussion, nobody names names. Nobody says this ethnic community is doing this. Everybody's talking about the scorpion. You know, at the end of it, we would have an apology. And then we would invite all the communities again to the football stadium, and they would stand there and the apology would be read with shaking hands and shaking voices but read anyway. And people would go home saying an apology has been read and it was very powerful. So the reason that I spoke about the 56 ethnic communities is that it held.

Melissa Fleming 18:00

The peace agreement that you drew up, was a peace agreement between 56 community ethnic communities who had all been in conflict and they all apologised publicly and signed this agreement. And to this day, it's still holding?

Alice Nderitu 18:19

It's still holding. One year later, they called me. They said ‘Come back’. I had already left and had gone off somewhere else and I went back in at the same stadium. We said ‘We are coming to tell you thank you.’ It was fantastic. It was great.

Melissa Fleming 18:34

How did you feel?

Alice Nderitu 18:36

I say to myself, if I don't ever do anything again in my life, I think this is enough. It was really, really something. It was really something.

Melissa Fleming 18:46

You found your formula then? This is an original. Alice mediation formula.

Alice Nderitu 18:54

Yes, yes. Tweaking here and there, giving lots of stories. At some point, they started calling me ‘Grandma’ which was such an honour because it meant that I had superseded that identity of just being that woman who came from Kenya to come and talk to us. Because of the stories. And then in some of the meetings I attended after that I was fascinated to hear them giving some of my stories in other places. I did a lot of radio work because usually what happens in these peace processes is that the community - the six people - eventually actually become good friends because they've been sitting together for one year, one and a half years, two years. They become good friends. But they are not able to carry their communities or the people they represent alone. People are so angry out there. But these people, we are sitting with in here, are so... begin to bond. At some point, we actually began a process where, when they were coming for meetings, we would arrange for them to come together. People from rival ethnic communities. We would tell them ‘Okay, when you're coming you have to come in one car, or you have to be seen together, like out there, coming together.’ It was very powerful. Because people will be saying, ‘Are we not supposed to be enemies and our leader is working with this enemy?’ So it was a whole process of…

Melissa Fleming 20:22

Symbolism too.

Alice Nderitu 20:24

Yes, symbolism.

Melissa Fleming 20:26

I'm also very curious, how do you come to be called to do this work? if you were working for a human rights or mediation organisation in Kenya? Who called you and said ‘Alice, come mediate our conflict, we can't stop killing each other anymore.’

Alice Nderitu 20:44

Initially, I was working for the government of Kenya. I was working for the Human Rights Commission then. You know, we had violence in Kenya in 2007 and 2008. When the election happened, then there was a dispute about who won the election. And it immediately triggered a bloodbath around the country. Neighbours were killing neighbours and we heard so many stories of ‘We never fought with this neighbour, we never disagreed. But one day, he just showed up and started slicing my children with a machete.’ You know, like, those were the kinds of stories that were coming out. It was horrible. So then, we kept writing, we kept documenting. At some point, even we had to wear our Red Cross jackets and go out to people and try to save people. And that's how it happened.

Melissa Fleming 21:34

What were you doing in particular, where were you? And what did you witness?

Alice Nderitu 21:39

I was in charge of Human Rights Education. But we were in the field. I saw lots of people killed. Lots of dead bodies on the roads.

Melissa Fleming 21:52

Just driving by there were dead...

Alice Nderitu 21:54

Oh yes, everywhere. In fact, when I went back to Nairobi, I have a son and he was young, he was 10 years old. One day, we found somebody who had been...who had really...he was severely injured, and he was asking for help. Then we put him in the car, we drove to the hospital, which wasn't very far. Unfortunately, he died before we got to the hospital, then the hospital wouldn't take him and I had a 10-year-old in the car. And I was telling him, ‘He's just sleeping.’ I didn't want him to know. So then I had to take him to the mortuary and write statements at the police station about where I found him. And you know, those kinds of things. So there are so many things happening, so many, many, many, many things happening.

Melissa Fleming 22:37

How did that affect you to see, I mean, you had a young man dying in your car in the presence of your son. You were seeing, I mean, you were warning of this, and then it was happening.

Alice Nderitu 22:49

It was happening. And I was calling my boss and calling everyone and saying ‘Please come and help. Like, I don't know what to do with this.’ Then one of my colleagues came in, he helped. And meanwhile, it was very dangerous at that time to even drive through the city. Because there were so many roadblocks, and I would flash my human rights card everywhere, like ‘Hey, I work for human rights. I work for human rights.’

Melissa Fleming 23:10

Did you feel that that card would protect you?

Alice Nderitu 23:12

Yes, it did. Because many of the people we met were so afraid. They were mobs that were looting and that we're doing so many things. So I would flash my card and I would say ‘I work for you. I work for human rights.’ And then we managed to get back home and afterward I felt very sorry for having exposed my son to all that. I felt very, very, very, very sorry.

Melissa Fleming 23:37

What did he say to you?

Alice Nderitu 23:39

He told me, much later, that he knew. He realised that when we were at the hospital, there was something really bad that had happened to the man. But it took me a long long time to understand in a community that doesn't do therapy, how stressed I used to be by what I exposed my son to. Like it was more of ‘What did I do to my child? Will he ever see things the same way again, after this? And how far can I take my human rights activism? What have I done?’ Until when I went to San Diego, a therapist spoke to me and she told me that I have to have this image in my mind in which I’m a sieve and not a container that things have to pass through. It was so powerful. All the time when I'm in all these conflict situations, and I see all these things, I leave and then I say to myself, 'You're a sieve, you’re a sieve.’ I keep saying that to myself. ‘You are not a container, you’re a sieve’, so that things pass through. So for my son, he told me that, on that day, he just made the decision that he will not… ‘I'm not going to do the kind of work that you do. One of us is enough in this family to do this. We can’t both do this.’

Melissa Fleming 25:02

Did he keep true to his word?

Alice Nderitu 25:06

Not quite because he studied finance and then he became very interested in filmmaking. Then he completely changed track. He’s stopped the finance now. He's a filmmaker, and he focuses on social justice issues. So it's a very interesting dynamic. I don't tell him’ Okay, even this is part of this’. But that's what he does now. It's been very gratifying for me to watch him become a filmmaker of his own volition without me pushing him. He did so many online courses, he just went and became a filmmaker and it makes me very happy.

Melissa Fleming 25:44

You mentioned that you had an opportunity to go to San Diego at one point in your career. Can you just describe why San Diego, why they invited you, and what was it like there?

Alice Nderitu 25:59

In San Diego, at the Institute for Peace and Justice, they have what they call a Women’s Peacemakers Programme. They invite women who are involved in peacemaking, who are working in very volatile situations, who just need a break. And you also meet this whole team of other women who are going through what you're going through. And that's where I met a therapist for the first time I started with a therapist, who told me that I have to be a sieve, not a container and it was really, really good.

Melissa Fleming 26:30

I know that you have a lot of ideas for your new job. I believe you're only about three months into your new job as the Secretary General's Advisor on Prevention of Genocide. What does that entail and what are your plans?

Alice Nderitu 26:46

I have a mandate, a very powerful mandate. And the mandate is to be a catalyst where I provide early warning, where I draw attention to things that are going wrong, where we have indicators for atrocities happening, the genocides happening, and to then advise the Secretary General. Who then in turn advises the Security Council. But the whole mandate is around paying specific attention to ensuring that genocides do not happen by pointing out what is going on on the ground before it happens.

So I've spent a lot of time reading a lot, watching the news, speaking to a lot of people. One of the things that I found to be very powerful, is to ask people to just look out through the window and tell us what they're seeing, ‘What are you seeing?’ Then people say things like, ‘I'm seeing children, the schools are not open today.’ That's already an indicator of something strange going on. ‘I'm seeing people meeting in small groups,’ another indicator. ‘I was in the market and ethnic communities are not buying from each other,’ another indicator, or ‘Religious communities are not buying from each other,’ another indicator. So many things that keep coming up. So my key work is to find as much information as possible, and then analyse it, analyse it in such a way that it can be presented as risk factors leading to violence.

Melissa Fleming 28:26

That's quite a lot to cover. I mean, it's a big world, what is keeping you awake at night these days?

Alice Nderitu 28:33

What's keeping me awake at night is the same thing that kept me awake 10 years ago, 20 years ago. All these people who know that violence is going to happen and they do not know who to tell. And all these people who know that violence is going to happen and they know who to tell and that person either has the inability or does not want to do something about it. So all those people sitting somewhere and knowing ‘I can be attacked tomorrow or I will be attacked tomorrow’ and they do not know who to tell. It keeps me awake at night. I think about it a lot. I know a lot of those kinds of people. And now that I'm in this position, they expect me to do something about it.

When the announcement was made that I had been appointed into this position, I couldn't use my phone for three, four days. I couldn't. It was ringing off the hook. Messages were coming in. So many people, so many people around the world, saying, ‘You know you're getting in there,’ giving advice, telling me about their situations. And I kept telling them ‘I haven't even reported, it's just been announced. And they were saying ‘You know, we are going to be attacked tomorrow. You have to do something. You have to know somebody, whoever appointed you, you have to know.’ That kind of thing. And it's a tough place to be in when every night you're going to bed knowing that somebody somewhere knows they're going to be attacked, and they don't know who to tell.

Melissa Fleming 30:08

You know, after the Holocaust, the world said ‘Never again.’ And we've had horrific other instances of genocide in recent history. Has the world learned anything?

Alice Nderitu 30:22

The world has learned something. Each time we talk about the name of our office, people don't even want to hear the name ‘genocide’. And so they know that it's something that shouldn't be done. But we've said never again, we keep saying never again, but the atrocities keep happening. And genocide is, of course, a human creation. So really, there has to be a human solution to it. There is still so much that needs to be done to strengthen response. And I think what the world hasn't learned is what to do about the response. Because the early warning is there, you will speak to people everywhere, they give you a lot of information on what is going on. But response is extremely poor.

You find sometimes genocide becoming a comparison of the numbers killed. There’s still so much, still so much to do. At this particular point, I feel very strongly that we need to put a lot of focus on the reasons why people actually get to genocide. Right now, we are doing a lot of work on hate speech, for example. I don't think we are doing enough in terms of working to understand why those who did it, did it. What kind of foundations did they come from? What is it we can address within those foundations? How can we interrupt the cycle of socialisation that produced this person who keeps spewing out this hate? What is it? At what stage in life, should we be looking at a person so that we understand that we need to look at this person when they are in kindergarten or when they are in primary school, in lower school? Or when they are teenagers? At what point should we get in there? So I think we need to invest a lot of energy. For ‘never again’ to work, we need to invest a lot of energy in addressing the foundations that produce these kinds of people who end up becoming genociders.

Melissa Fleming 32:42

Here's my last question to you, Alice. I mean, you're taking on a lot of heavy emotion, the calls from people who are worried about violence that you were just describing, and in this role preventing genocide, you must do some things for fun. Is there anything that you'd like to share what you do for fun just to relax and to take your mind off some of the awful aspects of your work?

Alice Nderitu 33:13

Yeah, because of my son I have this ‘Must watch a movie every week’ and the movie is not about atrocities. But I tell you, I don't want a simplistic movie, I want something that will make me think. And I read a lot so reading is very good for me. I have my community of friends and we speak a lot about our issues. We have a WhatsApp group where you just post funny things, and you just laugh and you just relax. And then that being a sieve really helps so I do my walks and….

Melissa Fleming 33:55

Now you’re here with your husband in New York City, during a pandemic. What a time to move to New York.

Alice Nderitu 34:02

What a time to move to New York! And you know, my husband is from Ghana, he's from Accra. So we came from Accra where people are walking around. The lockdown, I think we had a two-week lockdown. People were walking around and there wasn't quite the kinds of restrictions here. So in this space, it's just about engaging quite a lot, speaking with family, with relatives, just making sure that the days... my days, of course, have to be full of so much work. I am doing a lot of knowing the UN since I've just come into the UN, so there's quite a lot going on there right now.

Melissa Fleming 34:46

Welcome to the UN family, Alice, and good luck with everything you do. And thank you for joining us on Awake At Night.

Alice Nderitu 34:55

Thank you so much for having me.

Melissa Fleming 35:03

Thank you for listening to Awake At Night. We'll be back soon with more incredible and inspiring stories from people working to do some good in this world at a time of global crisis. To find out more about the series, and the extraordinary people featured, do visit un.org-awake-at-night. On Twitter, we're @UN and I'm @melissafleming. Alice is @wairimunderitu5. Subscribe to Awake at Night wherever you get your podcasts and please take the time to review us. It does make a difference.

Thanks to my producers, Bethany Bell, and the team at Chalk & Blade: Laura Sheeter, Fatuma Khaireh, and Alex Portfelix, and to my colleagues at the UN, Roberta Politi, Darrin Farrant, Hilary He, Tulin Battikhi, and Bissera Kostova.

Special thanks to the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs for their support. The original music for this podcast was written and performed by Nadine Shah, and produced by Ben Hillier. The sound design and additional music was by Pascal Wyse.