- عربي

- English

- Français

- Русский

- Español

LDC category at 50: Adjusting to the new realities

This article was published in the Trade Insight Volume 17 No. 3-4, South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SAWTEE)

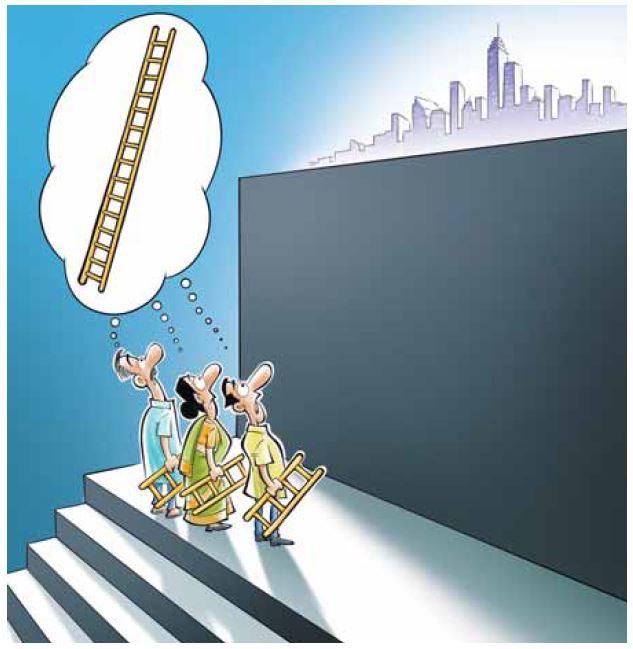

The failure to place productive capacity-building at the centre of the next ‘LDCs PoA’ will be a missed opportunity.

Taffere Tesfachew

November 2021 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the least developed country (LDC) category by the United Nation’s General Assembly (UNGA). To properly understand the challenges facing LDCs and the new realities moving forward, it is critical to have a full grasp of the thinking and strategic imperatives that led to the establishment of the LDC category, how they influenced LDCs’ development since then and their relevance in the present times.

The idea of creating a special category for low-income, structurally weak and ‘least developed countries’ originated in the first session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) held in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1964.1 Special attention was paid to the newly independent and marginalized countries and the challenges they faced in the international economic system, which was highly competitive and unfair to economies with limited productive capacities. To create a more balanced playing field, it was proposed that the international community support the least developed of developing countries with targeted international support measures (ISMs). Initially the proposal did not receive positive response, even from other developing countries. Four years later, at the second session of UNCTAD in New Delhi, India, the proposal to create a special group that required tailored and targeted support by the international community received more support. 2 It was based on this consensus that the UNGA established the LDC category in November 1971.

Subsequent to the UNGA’s decision, an expert group consisting of academics and experts from international organizations was assembled to deliberate on what was then called the ‘typology’ of developing countries and to assess the ‘general situation’ of the countries that could be characterized as the least developed among developing countries.3 The work of the expert group was influenced by the dominant economic school of thought of the time—the neoliberal economic model—which emphasized the importance of markets and integration into the international trading system.4 The neoliberal school considered the limited development of their markets and their poor integration into the international system as the root cause of the development challenges facing the poor and structurally weak economies. Based on this premise, two important strategic directions were emphasized.

The first strategy was the need to create a level playing field in the international trading system through targeted support. This principle became the basis for the subsequent formulation of ISMs, including through special and differential treatment in the rules and regulations governing the multilateral trading system.

The second was the need to fast-track trade-related policy reforms among LDCs to accelerate their integration into the international trading system and enable them to take advantage of the market access opportunities offered through the ISMs. Greater integration into the international trading system was considered an important precondition for economic growth, which would lead to increased income through exports, in addition to attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and learning from technology and knowledge transfer and diffusion. This also explains the focus of ISMs on preferential market access through duty-free and quota- free arrangements.

In short, this was the economic thinking that shaped the nature of the international support offered to LDCs and influenced the policy and strategic direction followed by them since the establishment of the category 50 years ago. Unfortunately, insufficient attention was given at that time to the fact that the international playing fi eld does not remain static but can change over time as technologies evolve and the rules, standards, and the degree of sophistication of the international economic and trading systems advance. The increasing globalization of the world economy has shown that the international playing fi eld is a moving target, and the challenge for structurally weak and latecomer economies has been how to catch up with the rapidly changing global economic landscape. This partly explains the slow progress in the number of countries meeting the criteria for graduation from the LDC category. From the original 25 countries identified as LDCs in 1971 the number has increased steadily, reaching a peak of 51 countries in 2003. At the time of writing this paper, the number of LDCs has decreased to 46, still nearly double that of the original list.5 Also noteworthy is that LDCs now comprise approximately 14 percent of the world’s population, although they account for less than 1.3 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and approximately 0.9 percent of global trade.

The decision to establish a special category for the economically vulnerable countries was commendable and necessary. Unfortunately, the premise for establishing the support measures was based on a hollow understanding of the complex process of economic development. They did not properly consider the dangers associated with increased integration of structurally weak economies into a rapidly evolving global economic system. The challenges currently facing most LDCs are as pervasive and constricting as they were when the LDC category was first established in 1971. The fact that only a small number of countries have graduated from the LDC category and some LDCs are now reluctant to graduate for fear of post-graduation uncertainties indicates that the formula for supporting LDCs introduced some 50 years ago was faulty and needs serious rethinking and adjustment. In this connection, the forthcoming United Nations LDC5 conference provides a timely opportunity to look back, draw lessons from recent experiences and align LDCs support needs with the rapidly evolving global realities. In the 20th century, we have seen countries move from low-income to middle- and high-income economies and catch-up with developed countries in less than 50 years. Sadly, however, since 1971, the number of LDCs has been increasing rather than decreasing, although more countries are expected to graduate within the current decade.

Back to the future: building productive capacities

Next year, the global community will gather in Doha to evaluate the progress made in the implementation of the Istanbul programme of action (IPoA). The forthcoming conference will also reflect on the lessons learned and decide on the Programme of Action (PoA) for the decade 2022-2031. The timing makes it a make-or-break conference largely because of the multiple and complex challenges, including post-COVID recovery, facing the LDCs and the urgent need for bold and innovative support measures needed to ‘build back better’ and regain the growth momentum necessary to meet the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by 2030. The root cause of LDCs’ economic vulnerability and structural impediments and their failure to catch-up with other developing countries is the limited development of their productive capacities. Failure to appreciate this reality, thus, failure to place productive capacity-building at the centre of the next LDCs PoA will be a missed opportunity and condemning LDCs to remain in the LDC-trap.

At present, the challenges facing LDCs are many and diverse. Some of them are unfulfilled goals left over from the IPoA, for example, the target of halving the number of LDCs meeting the criteria for graduation by 2020, which remains unmet. Other challenges are persistent and typical of resource-poor and underdeveloped economies, such as economic vulnerability, environmental resilience, structural weakness, job creation, resource constraints, among others. Ongoing commitments such as achieving the SDGs by 2030 and tackling climate change require more attention. Since 2020, LDCs are in added constraints to respond to the Covid-19 shock and taking measures to manage the post-Covid-19 recovery. All these issues are addressed in the outcome document for LDC5 which is currently under consideration by member states before submission for final decision at the Doha LDC5 conference. How far the final outcome will propose concrete and long-lasting solutions to many of the persistent challenges facing the LDCs is yet to be seen. In this brief discussion, the main focus will be on productive capacity building as an overarching development objective and a solution to many of the binding constraints that are hindering LDCs growth and development.

Reinforcing productive capacities

Owing to the heterogeneity of their economies, not all challenges affect all LDCs equally. However, there is one factor common to practically all LDCs. That is, the limited development of their productive capacities. This point is vital and LDCs and their development partners must realize that there is a limit to LDCs’ development, even after meeting the eligibility criteria for graduation, unless their economic progress is based on and driven by the expansion of domestic productive capacities. 6 Productive capacities are the diverse competencies, resources, skills, infrastructure, technological capabilities, institutions, and systems that a country needs to produce and export increasingly more sophisticated goods and services efficiently and competitively. 7 Even mitigating the impact of climate change and achieving all the social and economic targets of the SDGs are dependent on the development of productive capacities. In 2016, the committee for development policy (CDP) recommended that the LDCs adopt ‘expanding productive capacity for sustainable development’ as a framework for organizing the PoA for LDCs for this decade.

Both LDCs and their development partners recognize the critical role of productive capacities for lifting LDCs out of poverty and the low-value and low-technology production trap. Indeed, during the Fourth UN conference on LDCs in Istanbul, Turkey, in 2011, productive capacities were identified as one of eight priority areas for the decade 2011-2020. Whether, as recommended by the CDP, member states will go a step further and adopt productive capacities as a framework for organizing the next PoA for LDCs is not clear. Nevertheless, one hopes that the issue of productive capacities will feature prominently in the next PoA.

Adjusting to new realities

The COVID-19 shock has exposed the vulnerabilities of all countries, rich and poor; large and small; developed and developing. For LDCs, vulnerability to external shocks is not new. However, COVID-19 has further intensified their pre-existing economic and social vulnerabilities and exposed their limited capacity to effectively respond to external shocks. Unlike other countries, LDCs’ vulnerability evolves from their underdeveloped production system, which makes it structural in nature and in-built into what distinguishes them as LDCs.

Thus, moving forward, LDCs should aim to design a strategy that goes beyond getting back to pre-COVID- 19 growth and development trajectory. They should aspire to build the resilience that will ‘prepare them better’ for the next pandemic or future global crisis. In this respect, the hard lessons learned in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic must not be forgotten. When the virus began to spread globally in early 2020, the precipitous increase in demand for medical supplies, especially personal protective equipment (PPEs), generated important lessons for countries with limited productive capacities such as LDCs. Lacking the productive capacities to produce these essential medical supplies of the required standard, most LDCs resorted to importing from countries that have the productive capacities to manufacture them.

Unfortunately, this posed two types of problems: the first was securing adequate foreign exchange, which is a perennial problem in LDCs. Second, soon after the outbreak of the pandemic, countries that could produce medical supplies began imposing export restrictions to stockpile for domestic needs. Thus, even if foreign exchange was available, importing the essential medical supplies became a challenge. This situation was a wakeup call for LDCs that lacked the productive capacities to produce the medical supplies required to fight the virus and control the spread of infections. Faced with this unenviable dilemma, many LDCs introduced measures to encourage local enterprises to repurpose and start manufacturing PPEs such as face masks, medical gowns, gloves, etc. Some LDCs, like Bangladesh, were able to repurpose and manufacture PPEs, suggesting that Bangladesh’s export-led industrialization strategy has enabled the country to expand its productive capacities. Others, especially African LDCs, however, learned a bitter lesson that failing to build one’s productive capacities can have severe consequences under unexpected external shock conditions. Out of 25 African countries, most of them LDCs, that initiated repurposing programmes aimed at increasing local production of essential medical supplies, only a few succeeded in producing PPEs that meet the required World Health Organization standards and qualities.8 This experience reinforces the recommendation by the CDP that the LDCs should adopt expanding productive capacities as a framework for organizing the next LDCs PoA for the decade 2022-2031.

Aligning next PoA with the Agenda 2030

When the LDCs and their development partners met in Istanbul for the fourth LDC conference in 2011, the main international challenge for LDCs at the time was to achieve the millennium development goals (MDGs) by 2015. The primary goal of the MDGs was to halve extreme poverty by 2015 and register progress in the social sector, particularly in education and health. Since then, the international community has raised the stakes by setting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs). In contrast to the MDGs, the SDGs are more ambitious and have raised the bar by insisting on the balanced treatment of the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development, and incorporating the principle of leaving no one behind.

As LDCs prepare for the fifth LDC conference, two important points need special attention. The first is the alignment of the LDCs PoA for the decade 2022-2031 with the SDGs. For SDGs, this is the ‘decade of action’ and LDCs should ensure that their PoA for the decade reflects that reality. Second, LDCs must realize that achieving the diverse goals and targets specified in the SDGs will be practically impossible without developing productive capacities. Indeed, it was largely in recognition of the important interlinkages between developing productive capacities and achieving the SDGs that the international community incorporated Goals 8, 9, 10 and 17 as an integral part of the 2030 agenda. These goals form the basis for building transformative productive capacities.

Thus, by making the development of productive capacities a central feature of their PoA for 2022-2031, LDCs will establish a solid foundation for achieving the SDGs. As noted by the CDP, “Meeting many of the SDGs would require expanding productive capacity, upgrading technological capability, improving productivity, and creating more and better jobs. Thus, to achieve the SDGs in a balanced manner, countries will need to pursue a development strategy focused on the development of productive capacity”.9

Productive jobs

Recent experiences have shown that while economic growth is a desirable policy objective and important for increasing income and generating wealth, not all types of growth create decent and productive jobs in sufficient quantities to enable countries to eradicate poverty and achieve inclusive and sustainable development. In fact, there is an obsession in many LDCs about achieving high-level growth, regardless of the source and impact of growth. Experiences show, however, the source of growth matters for sustainability and job creation. Growth alone, even at a higher rate, is insufficient if it does not protect environment, create decent and productive jobs, improve living standards, reduce poverty, and result in widely shared prosperity. Labour force in LDCs increases by 13.3 million workers per year, most of them young people migrating to cities in search of decent jobs.10 Only by expanding productive capacities and creating productive jobs will LDCs be able to tackle the potential adverse consequences of youth unemployment and maintain peace and stability.

In short, creating jobs and giving people the opportunity to earn an income while being employed productively is the most effective and dignified way of eliminating poverty, which is one of the seminal goals of the SDGs. However, LDCs must realize that to create decent and productive jobs, it is essential that they diversify into productive sectors, invest in human capital development, and promote technological learning and innovation. Achieving these objectives will require shifting the policy focus to the development of productive capacities. It will also mean, above all, adjusting the focus and policy priority in LDCs PoA towards the development of productive capacities.

Dr. Tesfachew is Acting Managing Director at United Nations Technology Bank for Least Developed Countries; Senior Advisor at Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI) and Member of the United Nations Committee for Development Policy (UNCDP).

Notes

1 UNCTAD. 1985. The History of UNCTAD: 1964-1985. Geneva: United Nations.

2 UNCTAD. 1968. Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Second Session, New Delhi, 1 February – 29 March 1968 Volume I. New York: UN Publication.

3 UN. 1969. “Special measures in favour of the least developed among developing countries” (TD/B/288). Geneva: UN Publication.

4 Historical records show that a contrasting view was presented from the proponents of the structuralist theory of development, which was then advocated by UNCTAD and its Secretary-General, Raul Prebisch. For structuralist school, the wide income and development gap between the ‘least developed’ and more developed countries was the result of the continuing dependence of the poorer economies on production and exports of commodities and imports of higher-value manufactured products from developed countries. This was seen as a problem because of the inherent tendency for the prices of commodities to decline relative to developed-country exports (largely industrial goods), leading to a chronic deterioration in developing countries’ terms of trade and the widening of income gap between rich and poor countries. A fairer global trading arrangement and economic diversification at national level were believed to be the solution to this problem. For details, see Prebisch, R. 1964. Towards a New Trade Policy for Development. Report by the Secretary-General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). New York: UN Publication.

5 As of 2021, six countries have left the LDC category—Botswana (1994), Cabo Verde (2007), the Maldives (2011), Samoa (2017), Equatorial Guinea (2017) and Vanuatu (2020).

6 Both UNCTAD and the CDP have shown, in separate studies, the critical role of developing productive capacities for achieving progress not only towards graduation but also for sustaining economic development after graduation.

7 UNCTAD. 2006. Least developed Countries Report: Developing Productive Capacities. Geneva: United Nations.

8 Farrar, Jeremy, and Peter Sands. 2021. “Transforming the medical PPE Ecosystem.” Working Paper. The Global Fund, August 2021.

9 CDP. 2017. “Expanding Productive capacities: Lessons Learned from Graduating Least Developed Countries.” Policy Note. New York: Committee for Development Policy, DESA.

10 UNCTAD. 2020. Least Developed Countries Report: Productive Capacities for the new decade. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.