- ON THE DECADE

- THE DECADE'S CAMPAIGN

- REPORTING ON PROGRESS

- THE DECADE'S PROGRAMMES

- FOCUS AREAS

-

- Access to sanitation

- Financing water

- Gender and water

- Human right to water

- Integrated Water Resources Management

- Transboundary waters

- Water and cities

- Water and energy

- Water and food security

- Water and sustainable development

- Water and the green economy

- Water cooperation

- Water quality

- Water scarcity

- FOCUS REGIONS

- RESOURCES FOR

- UN e-RESOURCES

‘Water for Life’ UN-Water Best Practices Award

2014 edition: Winners

Background

The IWMI-Tata Water Policy Program (ITP) was initiated in 2001 as a co-equal partnership between the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, and Sir Ratan Tata Trust (SRTT), Mumbai. Its mandate is to undertake policy research in the domain of water-environment-agriculture-livelihoods. Besides several other relevant research themes, one of the cornerstones of ITP’s research has been on the Energy-Irrigation Nexus. ITP was not only the first to highlight the criticality of this nexus but has been at the forefront of developing ideas for co-management of energy and groundwater, both key facets of agricultural livelihoods in India.

The core concept behind ITP was that while there is a lot of potentially useful scientific research being conducted in India, it often does not reach the policy makers – who are willing and keen to learn from science – because neither the research objectives nor the research design are formulated with them in mind. Thus, ITP tried to fill the gap between research and policy action by simultaneously engaging with scientists and policy makers, by asking the right questions, and often by turning problems on their head to strive towards practical, action-able policy recommendations based on sound scientific principles. Towards this, ITP partnered with a large number of stakeholders and involved them in the process of research. ITP is also an example of an international scientific institute working – not as a grantee but as an equal partner – with an Indian donor to set the agenda for discussion, debate and policy action around India’s water-environment-energy-agriculture-livelihoods future.

Challenges

The challenges of the energy-irrigation nexus continue to be important in the Indian context, with different regions and states facing different challenges and trying out different solutions. While states like Gujarat and Punjab opted for feeder separation to improve rural power quality, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh have resorted to giving temporary power connections to farmers during peak irrigation period and trying to create an alternative regime of metered farm power supply.

In eastern and tribal central India, where groundwater is relatively abundant but villages often lack electricity supply, farmers are forced to depend on diesel to run their irrigation pumps. This creates a paradoxical situation where in regions with rapidly depleting groundwater, farmers get free or highly subsidized power supply (therefore they face no economic scarcity), while in regions with abundant groundwater resources farmers tend to economize on irrigation due to expensive diesel. As a result of this and other food policies, water scarce India ends up exporting ‘virtual water’ (embedded in agricultural commodities) to water abundant India. ITP researchers have argued that before India spends US$ 120 billion to physically transport water to water scarce regions, India’s food policies must sync with water (and land) endowments to correct the perverse direction of virtual water trade.

In eastern and tribal central India, where groundwater is relatively abundant but villages often lack electricity supply, farmers are forced to depend on diesel to run their irrigation pumps. This creates a paradoxical situation where in regions with rapidly depleting groundwater, farmers get free or highly subsidized power supply (therefore they face no economic scarcity), while in regions with abundant groundwater resources farmers tend to economize on irrigation due to expensive diesel. As a result of this and other food policies, water scarce India ends up exporting ‘virtual water’ (embedded in agricultural commodities) to water abundant India. ITP researchers have argued that before India spends US$ 120 billion to physically transport water to water scarce regions, India’s food policies must sync with water (and land) endowments to correct the perverse direction of virtual water trade.

Actions

Considering these recommendations from the scientific community, in 2005-2006, the Government of Gujarat launched the Jyotirgram Yojana (JGY) programme and spent Rs. 11.7 billion (US$ 250 million) to completely re-wire the state by separating agricultural feeders from domestic and industrial ones. This was done in conjunction with broader structural and organizational reforms in the Gujarat Electricity Board. The agricultural feeders were now offered 8-hours of uninterrupted, high quality power supply as per a pre-announced bi-weekly roster while the domestic and industrial feeders were offered 24*7 power supply at commercial and near-commercial tariffs. Several studies on the impact of JGY, including the ones carried out by ITP found substantial benefits of JGY in terms of improvements in quality of rural life as well as impact on the farm economy. The Government of India has now accepted Gujarat’s Jyotigram initiative as a flagship scheme for its 12th five-year plan for the power sector.

By providing regular and reliable full-voltage power, Jyotigram Yojana (JGY) made it possible for farmers to keep to their irrigation schedules, conserve water, save on pump maintenance costs, use labour more efficiently and expand their irrigated agriculture rapidly. While the gross domestic product from agriculture grew at just under three per cent per annum for India as a whole, Gujarat recorded nearly ten per cent growth in the seven years from the project’s inception in 2003 - the highest in India. While other factors have also contributed to this growth, JGY is definitely one of the key drivers of agrarian growth in Gujarat.

By providing regular and reliable full-voltage power, Jyotigram Yojana (JGY) made it possible for farmers to keep to their irrigation schedules, conserve water, save on pump maintenance costs, use labour more efficiently and expand their irrigated agriculture rapidly. While the gross domestic product from agriculture grew at just under three per cent per annum for India as a whole, Gujarat recorded nearly ten per cent growth in the seven years from the project’s inception in 2003 - the highest in India. While other factors have also contributed to this growth, JGY is definitely one of the key drivers of agrarian growth in Gujarat.

Lessons learnt

This practice has shown that practical solutions are sometimes better than optimal ones. JGY kept all parties happy and delivered spectacular results both for farming and water conservation. Pricing might have been a more straightforward solution, but it was unpalatable to farmer groups.

Partnerships and relationship building are critical in research for sustainable development. IWMI-Tata influenced policy uptake, but support from other research institutions and fostering good relations with government ministers, building their capacity and understanding, also played a significant role.

The initiative was shown that research uptake works best when it responds to issues already high on the political agenda.

Background

At the time of independence in 1965, the city-state of Singapore was almost completely dependent on outside sources. Dilapidated buildings and squatter sheds in the business hub of the city centre were basically slum colonies and its riverways and canals resembled open sewers. Apart from the downtown core, other areas remained villages, with most of the population living in slums and kampongs without a proper water supply, sanitation or adequate public transport.

At the time of independence in 1965, the city-state of Singapore was almost completely dependent on outside sources. Dilapidated buildings and squatter sheds in the business hub of the city centre were basically slum colonies and its riverways and canals resembled open sewers. Apart from the downtown core, other areas remained villages, with most of the population living in slums and kampongs without a proper water supply, sanitation or adequate public transport.

In the short term of 20 years, Singapore policy makers moved impressively towards strengthening internal capacities and reducing its reliance on outside sources based on some of the best policy, planning, managerial, governance, education, science and technology focused approaches globally.

What is NEWater?

NEWater is high-grade reclaimed water produced from treated used water that has undergone a stringent purification and treatment process using advanced dual-membrane (microfiltration and reverse osmosis) and ultraviolet technologies. It has passed more than 100,000 scientific tests and exceeds the drinking water standards set by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

How is NEWater used?

NEWater is used primarily for non-potable industrial purposes at wafer (silicon circuits) fabrication parks, industrial estates and commercial buildings. This is important as the non-domestic sector currently accounts for 55% of Singapore’s water demand and this could increase to 70% by 2060. During dry months, NEWater is used to top up the reservoirs and blended with raw water before undergoing treatment at the waterworks before it is supplied to consumers.

NEWater is used primarily for non-potable industrial purposes at wafer (silicon circuits) fabrication parks, industrial estates and commercial buildings. This is important as the non-domestic sector currently accounts for 55% of Singapore’s water demand and this could increase to 70% by 2060. During dry months, NEWater is used to top up the reservoirs and blended with raw water before undergoing treatment at the waterworks before it is supplied to consumers.

Currently, NEWater can meet 30% of Singapore’s daily water needs, which stands at about 1500 million litres a day. NEWater capacity will be increased to meet 55% of Singapore’s future water demand by 2060.

Promoting sustainable water management in Singapore

The main objective of the NEWater program is to provide a sustainable water source for Singapore’s population. Within this framework, the work of the Public Utilities Board (PUB) has been crucial to its sustainable development. PUB strategy has included ‘Four Taps’ – expansion of catchment areas, water imported from neighbouring Johor in Malaysia, desalination and NEWater.

The main objective of the NEWater program is to provide a sustainable water source for Singapore’s population. Within this framework, the work of the Public Utilities Board (PUB) has been crucial to its sustainable development. PUB strategy has included ‘Four Taps’ – expansion of catchment areas, water imported from neighbouring Johor in Malaysia, desalination and NEWater.

The programme, created in 2002 has made a significant difference to sustainable water management in Singapore and enabled PUB to close the water cycle, increase clean water availability for domestic and industrial uses and increase water efficiency.

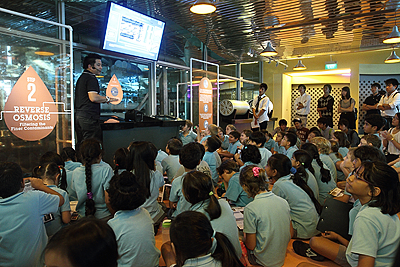

Educating and engaging the people on the NEWater approach

While reclaiming used water is not a new concept, what is significant is the successful wide-scale implementation and public engagement plan of NEWater along with its participatory practices and public education programmes, which have allowed delivery of an exponentially successful service.

While reclaiming used water is not a new concept, what is significant is the successful wide-scale implementation and public engagement plan of NEWater along with its participatory practices and public education programmes, which have allowed delivery of an exponentially successful service.

An effective public communications plan was also necessary to convince the public that NEWater is safe for consumption; and the industry that it is suitable for their processes.

PUB’s public communications plan included addressing technical issues, briefings to Members of Parliament, leveraging on the media, setting up a NEWater Visitor Centre etc. The public education campaign continued in schools, community centres and workplaces. At the industry level, wafer (silicon circuits) fabrication factories needed to be convinced to switch. To increase the industry’s confidence, a pilot plant was built to simulate the conditions at the factories. The product water was analysed and tested to the satisfaction of the wafer fabs.

>> FAQs

>> Statutes

>> Categories

>> Chinese![]()

>> English![]()

>> French![]()

>> Spanish![]()

>> By numbers

>> Candidates

>> Evaluation committee

>> Selection committee

>> Finalists

>> Winners

>> Ceremony

>> By numbers

>> Candidates

>> Evaluation committee

>> Selection committee

>> Finalists

>> Winners

>> Ceremony

>> By numbers

>> Candidates

>> Evaluation committee

>> Selection committee

>> Finalists

>> Winners

>> Ceremony

>> By numbers

>> Candidates

>> Evaluation committee

>> Selection committee

>> Finalists

>> Winners

>> Ceremony

>> By numbers

>> Evaluation committee

>> Selection committee

>> Candidates

>> Finalists

>> Winners

>> Ceremony

Copyright | Terms of use | Privacy notice | Site Index | Fraud alert | Help