More than a hundred years ago, the Spanish flu pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people – about 2.5 per cent of the then global population. Pandemic influenza outbreaks have been predictably unpredictable in the years since 1918, says the World Health Organization (WHO). The only certainty is that they are always global, and need a global response – supported by mobilization of partnerships and resources.

New diseases have been emerging at the unprecedented rate of one a year for the last two decades, and this trend is certain to continue. Here, we look at a small fraction of past pandemics and outbreaks, and the importance of solidarity, international cooperation and partnerships to prevent, detect and respond to these global challenges, while we tackle the immense challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

State of Immunization Today

Even before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, WHO and UNICEF reported that an estimated 20 million children worldwide – more than 1 in 10 – have been missing out on life-saving vaccines such as measles, diphtheria and tetanus, based on recent data.

Although there is still no vaccine for COVID-19, children should continue to be immunized against other deadly and highly contagious vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles and polio, while following national and local guidance on protective measures, says UNICEF.

During this year’s World Immunization Week (24 to 30 April), WHO issued new guidance to help countries protect critical immunization services during COVID-19, “so that ground is not lost in the fight against vaccine-preventable diseases.”

The science is clear: vaccines, when they are available, are the most effective tool to prevent outbreaks.

Visit WHO’s website, for more information and a full list of disease outbreaks as well as its global immunization coverage. Find out more about the recently launched global collaboration – COVID-19 Tools (Act) Accelerator – to accelerate the development, production and equitable access to new COVID-19 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines.

I. The End of Smallpox

SP Vaccine Lab/WHO

Last year, the WHO marked the 40th anniversary of the eradication of smallpox, calling it a testimony to what we can achieve when all nations work together. This milestone laid the foundation for stronger national immunization programmes worldwide, supporting the development of primary health care in many countries and creating momentum toward Universal Health Coverage.

By 1990, through national immunization programmes, 80 per cent of the world’s children were vaccinated against six major diseases – tuberculosis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles and polio.

Moreover, the percentage of children receiving the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) vaccine is considered an indicator of strengthened national routine immunization services, says UNICEF. By 2018, the vaccination coverage rate for DTP reached nearly 90 per cent from 72 per cent in 2000 and 20 percent in 1980.

II. The Polio Eradication Effort

Polio Vaccination in Iraq. United Nations photo: Sebastian Meyer/ WHO Iraq

Polio still exists in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria but its cases have decreased by more than 99 per cent since 1988, from over 350,000 to 33 reported cases in 2018, as a result of the global effort to eradicate the disease, says WHO.

The push to immunize the world’s children against polio, under the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), spearheaded by WHO, UNICEF, Rotary International, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), GAVI and a group of international financial partners, was launched in 1988 with the support of 165 countries.

Due to the equitable access to polio vaccination, more than 2.5 billion children have been vaccinated since the launch of the partnership, with help from some 20 million volunteers. Called one of the most ambitious global health programmes, the scale-up of the eradication effort – the core tenet of the partnership – is said to have prevented the paralysis of 18 million people and 900,000 deaths.

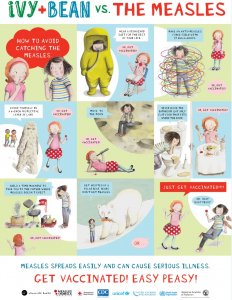

III. The Measles Vaccine

Before the launch of the Measles & Rubella Initiative (M&RI), a global partnership led by the American Red Cross, the UN Foundation, CDC, UNICEF and WHO, in 2001, more than 562,000 children died worldwide from measles complications each year.

Before the launch of the Measles & Rubella Initiative (M&RI), a global partnership led by the American Red Cross, the UN Foundation, CDC, UNICEF and WHO, in 2001, more than 562,000 children died worldwide from measles complications each year.

In 2018, M&RI continued to support 37 countries, implementing measles campaigns that reached more than 350 million children with bundled vaccines, operational costs or technical assistance.

Unfortunately, despite having a safe and effective vaccine for over 50 years, measles cases have surged over recent years, claiming the lives of more than 140,000 children in 2018 – all of which were preventable, warns the initiative. Top ten high-income countries, where children were not vaccinated with the first measles vaccine dose (2010 to 2018), include the United States (2,868,000), France (680,000) and the United Kingdom (585,000).

On top of this already precarious situation, preventive and responsive measles vaccination campaigns have now been paused or postponed in 24 countries due to COVID-19.

Image: In 2014, M&RI partnered with the American Academy of Pediatrics, and author and illustrator Sophie Blackhall to launch the “Ivy + Bean versus The Measles” campaign featuring characters from the children’s book series.

IV. The Containment of SARS

SARs treatment in Singapore. Photo courtesy: Tan Tock Seng Hospital/ WHO

In 2003, the SARS outbreak affected 26 countries, resulting in more than 8,000 cases and over 800 deaths. In response to the quickly spreading outbreak, WHO put in place a programme of global alert and rapid containment. It issued emergency guidance for travelers and urged airlines to watch for and report illness among passengers who had traveled to affected areas.

Moreover, the organization mobilized its network of over 250 technical institutions, deploying staff and resources to affected countries. Electronic networks connecting WHO with countries and regions across the globe made it possible to use real-time information to control the spread of SARS.

Five months after it began its spread, and without the use of vaccines, the outbreak was declared contained – showing that an outbreak can be contained even without a curative drug or vaccine if existing interventions are tailored to the circumstances and backed by political commitment, says WHO. Since then, SARS has reappeared four times, mostly due to laboratory accidents.