25 January 2022

On 22 March 2018, one of the most famous resistance heroes from the Netherlands, Johan van Hulst, passed away at the age of 107. His personal history is closely connected with the former Protestant Teacher School on Plantage Middenlaan in Amsterdam, of which he was the director during the Second World War.

The Teacher School is located opposite the Hollandsche Schouwburg, a former theatre. In 1942 and 1943, for a period of 14 months, the building was transformed by the Nazis into a transition centre for 46,000 Dutch Jews who were being sent to death camps in Eastern Europe. During those months, the theatre was often overfilled, and children were sent to a Jewish childcare centre across the street, next door to the Teacher School.

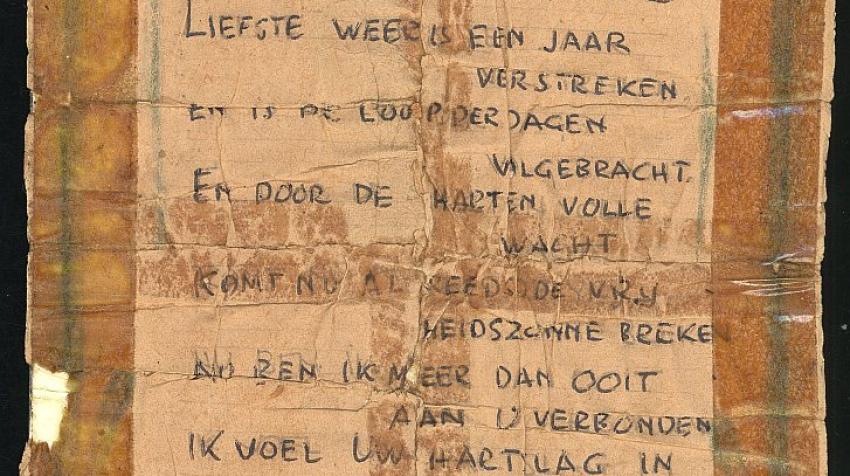

Johan van Hulst built a relationship of trust with the leadership of the childcare centre; as a result, babies would sometimes be allowed to sleep in one of the classrooms of the Teacher School. They were handed over the hedge in the backyard and brought into the school. This was done while the tram running in the street was stopped in front of the theatre, thus blocking the view of the German guards stationed there. In due course, and with the help of resistance groups, 600 children were moved from the Teacher School to different hiding places. Apart from Van Hulst, this touching story of rescue is also tied to the personal heroism of the director of the childcare centre, Henriëtte Henriquez Pimentel, and her young Jewish nurses. All those involved who survived the war had to live with the trauma of not having been able to save more children. Henriëtte Henriquez Pimentel was eventually murdered in Auschwitz.

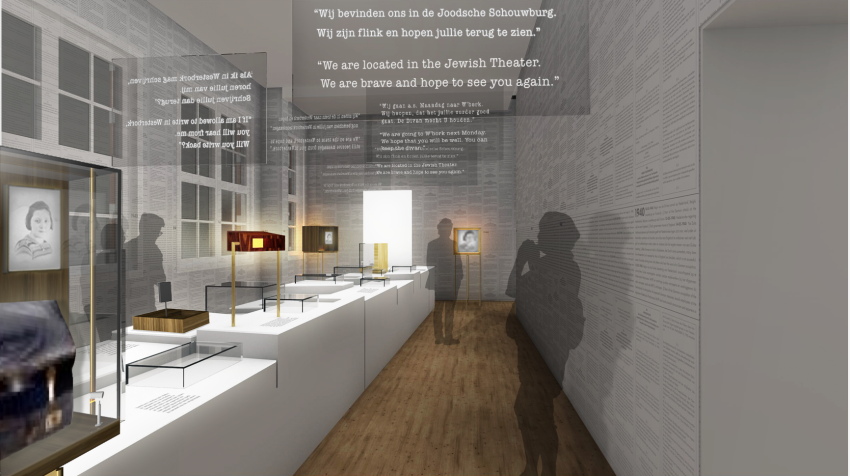

In the summer of 2023, Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter will open the National Holocaust Museum in the former Teacher School and the Hollandsche Schouwburg. The Netherlands will be one of the last Western European countries to establish such a museum, coming more than 75 years after the Second World War. The new Museum will not only deal with the history of the Holocaust proper, but it will also show the enormous effect that it had on Dutch society, Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

The National Holocaust Museum aims to confront people with the consequences of indifference, discrimination and exclusion, then and now. The Jewish Cultural Quarter has stated that “information about this dark chapter in history is of inestimable value. It forms a powerful tool for recognizing threats to our society and perhaps even averting them. That is how this Museum can contribute to a society where everyone’s rights are safeguarded.”

The biggest challenge for the National Holocaust Museum lies in the inevitable fragility of dealing with memory at two historical sites with different functions. The theatre is an official place of commemoration, whereas the Museum provides a complex visitor experience, curating and presenting historical fact without violating or even blurring the authenticity of memory. Curating and presenting historical fact are particularly important in today’s information-loaded society. Museums, universities and other institutions with educational missions share a responsibility to provide the world with reliable, easily accessible, unfiltered information on the Holocaust, arguably the greatest atrocity in the history of the twentieth century.

The Netherlands has a global reputation of tolerance, liberalism and political stability. Traditionally tolerant views and liberal laws on the use of hard and soft drugs, abortion, the integration of minorities, gay marriage and euthanasia are often viewed by other Western countries with astonishment and envy. One of the oft-heard explanations for why tolerance is prevalent in the Netherlands is the presence of a centuries-old sense of economic, social and ethical pragmatism. From this perspective, a well-functioning society is best served by the inclusion rather than the exclusion of new ideas, of newcomers, of new medical developments, of progress in general.

But does this still reflect reality? It has often been argued that there is but a thin line between tolerance and societal indifference. It cannot be denied that in recent decades, the concerns and fears of “ordinary” citizens were not addressed adequately. Right-wing politicians, who also consider themselves liberals, capitalize on this. They argue that traditional tolerance has led to a country under constant danger from Islamist religious fanatics, or to a dangerous “homeopathic dilution” of Dutch identity, or to unreasonable COVID-19 restrictions imposed by a presumably unreliable government. Time and again, Jews, the Holocaust and even the politics of the State of Israel are introduced into these discussions, regardless of their relevance.

Likewise, the commemoration of the Holocaust is a constant source of disagreement between Jews and non-Jews, and between the political left and right. It took the Dutch decades to face the raw fact that a higher percentage of Jews were deported from their country than from any other in Europe, with the exception of Poland. Of an estimated 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands prior to the Second World War, 102,000 were murdered. Instead of coming to terms with this legacy, heroic stories of resistance against the Nazis were celebrated and blatant cases of private and official collaboration were comfortably ignored. In Amsterdam and The Hague, among other cities, Jews returning from the camps were welcomed by the municipalities with tax assessments for overdue ground leases accumulated during their forced absence from the country, to give but one example.

The 1970s and 1980s did see an increase in public awareness of the fate of the Jews, which was often, but not exclusively, instigated by members of the post-war generation who wanted to come to terms with the shocking historical facts. This led to the installation of numerous memorials dedicated not to the war experience of the Dutch but to that of Dutch Jews.

Nevertheless, discussion continues. National Remembrance Day, which commemorates Dutch citizens and soldiers who died in war or in peacekeeping missions since the outbreak of the Second World War, is held annually on 4 May, followed by Liberation Day on 5 May. These observances have become a consistent source of public, Jewish and non-Jewish turmoil. What exactly should be commemorated? Who should be remembered? Should it include only the victims of the Second World War? Should only Dutch victims be commemorated or German victims as well? Could some of the perpetrators be considered victims as well? Should Jews, Roma and Sinti, and homosexuals not have separate status? And what about other minorities?

On 19 September 2021, the National Holocaust Names Memorial was opened in Amsterdam to enormous public recognition, which was not necessarily expected. The Memorial was designed by architect Daniel Libeskind and constructed of 102,000 bricks, each carrying the name of a Dutch victim, together forming the Hebrew word le-zekher—“in memory”. The Netherlands Auschwitz Committee wanted the monument to be visible, public and impressive, and serve as a kind of “never again” warning. Many Jews embraced the idea, but others, including several prominent figures, expressed strong objections ranging from “completely unnecessary” to “megalomaniacal.” A group of Amsterdammers even went to court to prevent the construction of the memorial. Since its opening, however, almost everyone agrees that it is an almost perfect memorial: moving, comprehensive and intimate.

What can museums do to inform such debates? The best answer is to do what they are good at: provide reliable information and prepare trustworthy curated interventions. Holocaust museums can accomplish this through exhibitions and educational programmes, and in particular, by developing new contemporary modes to discuss and commemorate the Holocaust. This may be ambitious, but as the first Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, once said, “in order to be a realist, you have to believe in miracles.”

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.