World Economic Situation and Prospects: September 2022 Briefing, No. 164

A bleak outlook for the global economy: Slowing growth, high and persistent inflation, and elevated uncertainties cloud global economic outlook

A bleak outlook for the global economy: Slowing growth, high and persistent inflation, and elevated uncertainties cloud global economic outlook

The global outlook has deteriorated markedly throughout 2022 amid high inflation, aggressive monetary tightening, and uncertainties from both the war in Ukraine and the lingering pandemic. Soaring food and energy prices are eroding real incomes, triggering a global cost-of-living crisis, particularly for the most vulnerable groups. Growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China, and the European Union—is weakening, with significant spillovers to other countries. At the same time, rising government borrowing costs and large capital outflows are exacerbating fiscal and balance of payments pressures in many developing countries. Against this backdrop, the global economy is now projected to grow between 2.5 and 2.8 per cent in 2022, a substantial downward revision from our previous forecasts released in January and May 2022. While the baseline forecast for 2023 is highly uncertain, most forward-looking indicators suggest a further slowdown in global growth.

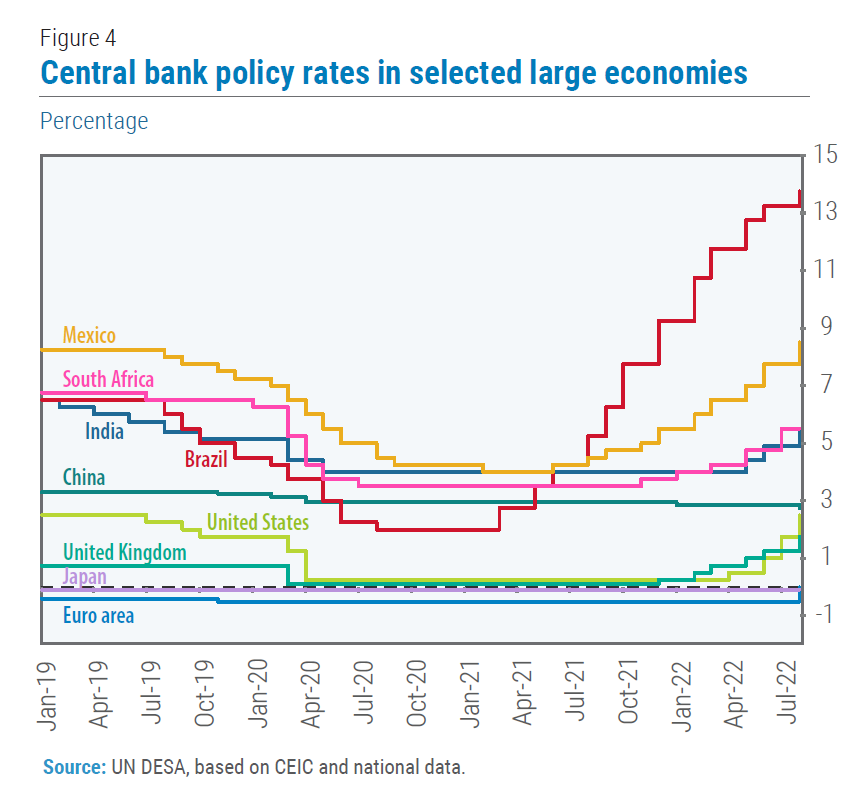

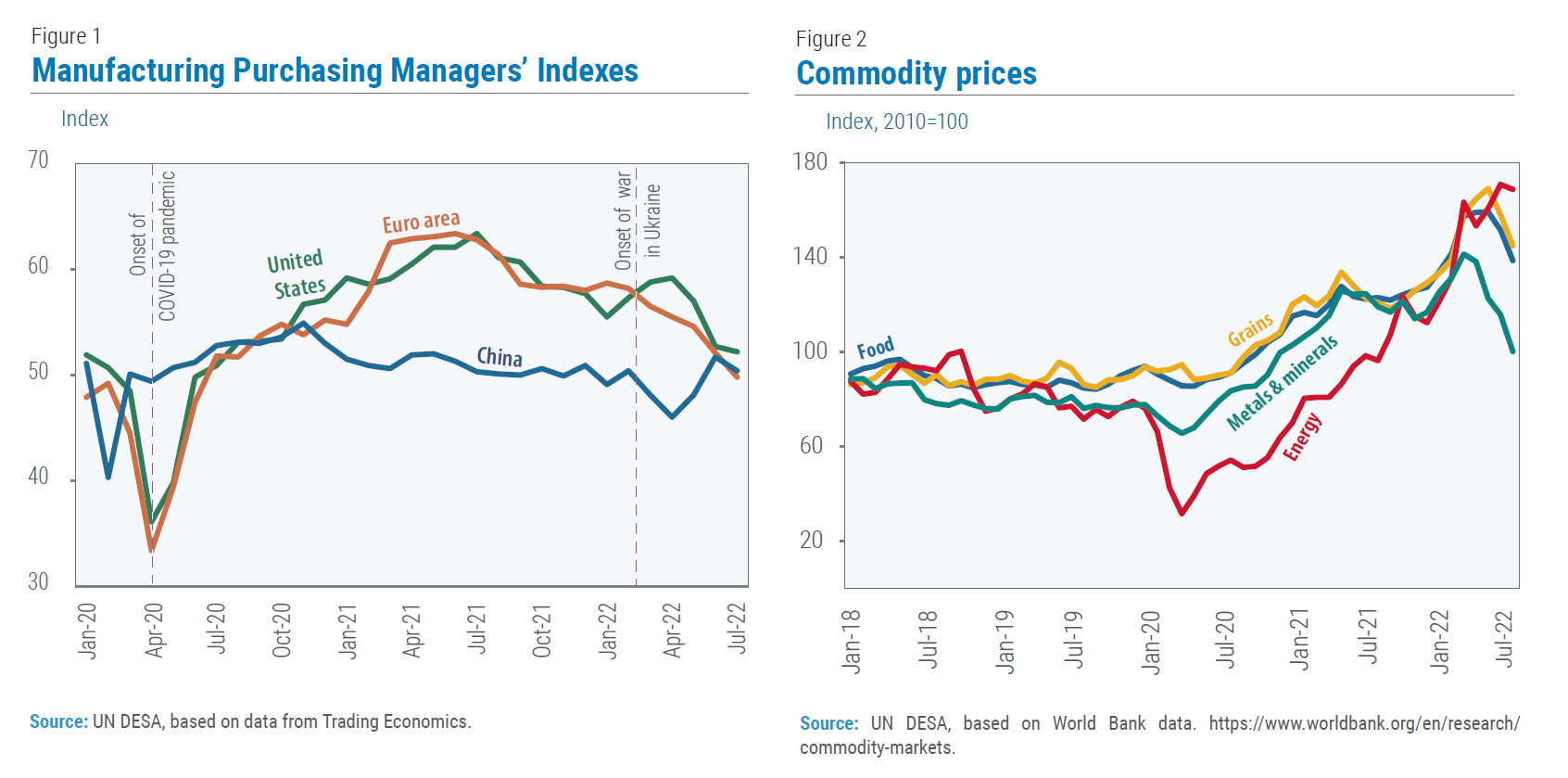

The manufacturing purchasing managers’ indexes—one key measure of business confidence—experienced broad-based declines during the past six months (figure 1). The deterioration in business confidence is particularly alarming for many developing countries that are yet to fully recover from the pandemic. International food and energy prices have fallen from recent peaks but continue to be at very high levels (figure 2). Global trade remains largely subdued as global supply chain disruptions and bottlenecks in international freight movements persist. The upward price pressures—reaching multi-decade highs in many countries—are hitting vulnerable population groups hard and prompting central banks to quickly tame inflation.

The world’s largest economies are facing sharp growth slowdowns

The economic outlook for the United States has deteriorated considerably amid high inflation, tight labor market conditions and aggressive monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve. After expanding by 5.7 per cent in 2021, GDP contracted in both the first and second quarters of 2022. Full-year growth forecasts have been downgraded to only about 1.5 per cent in 2022. Consumer spending, which accounts for about 70 per cent of economic activity, is expected to soften despite a still buoyant labor market that has recovered all the 22 million jobs lost at the outset of the pandemic. Amid an increasingly tight labor market, average hourly earnings in the private sector rose by 5.4 per cent in the first half of 2022. But with inflation averaging about 8.3 per cent during the same period, households are seeing their purchasing power erode and may start cutting back spending. Meanwhile, the strong dollar—which remains close to a 20-year high—will continue to exacerbate the US trade deficit. The housing market has taken a hit due to higher mortgage rates and soaring building costs, with residential fixed investment and home sales declining.

Growth in China is projected to slow to about 4 per cent in 2022 due to new waves of COVID-19 infections and rising geopolitical risks. In the second quarter, GDP growth fell to a two-year low of 0.4 per cent as strict measures were introduced to control the rise in cases of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. The growth momentum is expected to strengthen in the second half of 2022 and into 2023. Accelerated issuance of local government special bonds is set to boost infrastructure investment, while tax cuts will support businesses. With inflation below target, the central bank has maintained its supportive policy stance and lowered both its 5-year and 1-year rates in recent weeks. The Chinese economy faces major downside risks, including the re-emergence of new and highly transmittable variants of COVID-19. Although deleveraging measures in the real estate markets could improve macroeconomic stability in the medium term, they could trigger a wider financial sector crisis in the near term. In addition, still elevated urban unemployment could weigh on the recovery of private consumption. Rising geopolitical tensions between China and the United States add further uncertainties to the outlook.

The economies in Europe have so far proved resilient to the fallout from the war in Ukraine, but strong headwinds and downside risks persist. The region is facing triple pressures from the energy crisis, high inflation, and monetary policy tightening. Following a robust expansion in the first half of 2022—driven by further relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions and pent-up demand for services—GDP in the European Union is projected to grow by about 2.5 per cent this year. A potential total shut-down of Russian gas during the upcoming winter could lead to severe energy shortages and likely push Germany, Hungary, and Italy into recessions. Soaring energy and food prices are hurting households, with consumer confidence hitting a record low in July, falling even below the level at the beginning of the pandemic. A strong rebound in the labor market and exceptionally low unemployment rates in the European Union—ranging from 2.4 per cent in Czechia to 12.6 per cent in Spain—will likely provide some support to domestic demand.

Economies in transition show resilience

The economic prospects for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Georgia are heavily affected by the conflict in Ukraine and the stringent sanctions against the Russian Federation. Economic activity in the Russian Federation has so far defied expectations, with GDP declining by only 4 per cent in the second quarter of 2022. The strong appreciation of the Russian ruble helped stabilize inflation, sustaining private consumption and allowing the central bank to drastically cut policy rates. GDP is now forecast to contract by about 6 per cent in 2022, relative to our earlier projection of a 10.6 per cent decline. Most other CIS economies have also shown strong resilience, with the region’s energy exporters benefiting from high oil and gas prices. Inflation, however, reached very high levels across the region in recent months, threatening food security and forcing many central banks to sharply tighten their policy stances. The Ukrainian economy, however, faces enormous challenges, including destruction of physical infrastructure, suspension of production and trade activities, and displaced population. The post-conflict reconstruction will require immense financial resources.

Prospects for developing countries are weakening amid multiple challenges…

Many developing countries are fighting an uphill battle to fully recover from the pandemic, with high inflation, rising borrowing costs and the slowdown in the major economies further hurting their growth prospects. Despite the windfall of high commodity prices for the commodity-exporters in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, growth remains largely insufficient to mitigate the slack in labor markets. The ILO estimates that in developing countries, the gap in hours worked relative to pre-pandemic levels stood at— 6.0 per cent in the second quarter of 2022, compared to only—1.5 per cent in high-income economies.

In Africa, the slowing external demand from the European Union – its main trading partner, representing about 33 per cent of African exports – and waning monetary and fiscal support are constraining the recovery. Surging energy prices are benefiting oil-exporting countries, but net energy importers face rising pressures on current and fiscal accounts. Amid elevated levels of debt and rising borrowing costs, several governments are seeking bilateral and multilateral support to finance public investments. In many countries, there is increasing pressure to cut spending or raise taxes. Risks to regional security and domestic stability are rising as frustration mounts over inflation, lack of employment, and economic mismanagement.

The outlook in Latin America and the Caribbean remains challenging, amid aggressive monetary tightening, slowing growth in China and the United States, and domestic political uncertainties in some countries. Inflation remains close to multi-year highs in many countries. Higher oil prices are providing a windfall to oil-exporters such as Colombia, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Ecuador. Growth in Brazil – the largest economy in the region – remains subdued as fiscal cuts and political uncertainty add to the challenges. Given the region’s weak growth prospects, the scars from the pandemic will last for years, with poverty projected to increase further in 2022.

East Asia’s growth is expected to weaken in 2022. Higher commodity prices and rising interest rates are set to curtail spending and investment and slow the recovery. In addition, external demand is expected to soften as growth in the region’s main trading partners slows. In South Asia, higher global energy and food prices are severely affecting food insecurity. Tightening financial conditions, depreciation of domestic currencies and the spillover effects from the Ukraine conflict are creating fiscal and balance of payments pressures. India’s GDP growth is moderating, as high inflation and rising borrowing costs weaken domestic demand. Sri Lanka’s severe debt crisis, which has been accompanied by a major energy emergency and shortages of food and other essentials, illustrates the potential risks for many developing countries – most notably energy and food importers. In Western Asia, economic growth prospects have slightly improved due to high energy prices and waning adverse effects from the pandemic.

The outlook in the least developed countries (LDCs) – whose economies are most vulnerable to external shocks – is extremely challenging. As most LDCs are food and oil importers, the rise in global prices and the disruptions of global food supplies are severely impacting these economies, raising fiscal and balance of payment financing needs and increasing food insecurity. Growth is projected to remain weak in 2022, as rising food and energy prices increase living costs, erode real incomes and weaken domestic demand. Risks of a lost decade for many LDCs are rising amid high debt vulnerabilities and severe structural constraints, including insufficient fiscal space, large macroeconomic imbalances and lack of productive capacities. The short-term outlook in small island developing States (SIDS) also remains bleak, as tourism has not fully recovered from the pandemic. In 2022 the global tourism sector may reach 55 to 70 per cent of pre-pandemic levels, according to the UNWTO. In Asia and the Pacific, tourist arrivals in the first five months of 2022 were still almost 90 per cent below the 2019 level.

A global food crisis is hitting many developing countries

The war in Ukraine is severely affecting global food supplies. Food prices remain close to record highs, surpassing levels seen during the global food crises of 2007-2008 and 2010-2012, which sparked worldwide protests, particularly in Africa. A recent agreement between Ukraine and the Russian Federation to allow the resumption of grain exports from Ukrainian ports provided some relief, but its duration remains uncertain, and the conflict still weighs on Ukrainian agricultural production. The war is also contributing to high energy prices, which will affect forthcoming harvests as farmers cut back on sowing and planting given the high cost of running farm equipment, transportation, and fertilizer. A scorching summer season and increasing climate-related disasters are adding uncertainty and putting harvests at risk. Food prices are projected to stay high, and the risk of severe food shortages could remain for years.

Amid high food and fertilizer prices, the appreciation of the dollar and diminished fiscal space, low-income countries in Asia and Africa are most at risk. For example, food insecurity has exacerbated in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Sudan. A few developing countries are implementing or considering food export restrictions (e.g., India, Indonesia, Malaysia), which in turn will raise the cost of food imports for others. In addition, many governments are struggling to subsidize vulnerable households most at risk, as well as supporting farmers. A scramble for food may push millions into famine and cause social unrest and mass migration. High prices have already provoked protests in countries such as Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Sudan.

The global food crisis presents a major challenge to sustainable development. In June 2022, the UN warned that the world is moving further away from its goal of ending hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms by 2030. The number of people, particularly women, facing severe food insecurity has soared from 135 million in 53 countries before the pandemic to 345 million in 82 countries.

Central banks are changing course: Surging inflation prompts aggressive monetary tightening

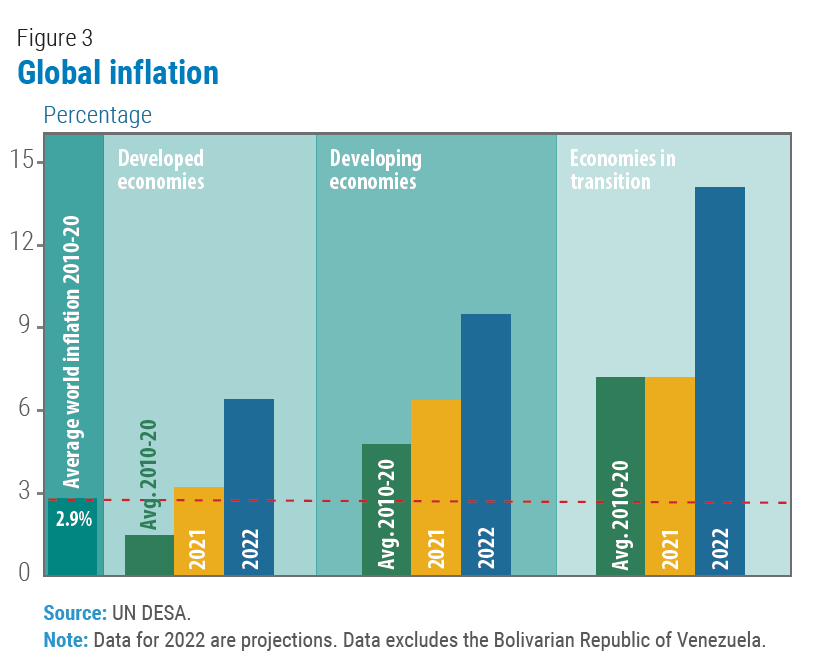

After a long period of price stability, inflation has returned with a vengeance in many countries (figure 3), eroding real incomes and triggering a global cost-of-living crisis. The pandemic-induced inflationary pressures have proved to be persistent, with demand recovering quickly and supply facing major hurdles and disruptions. The war in Ukraine, soaring food and energy prices and renewed supply shocks have not only fueled a surge in inflation, but also pushed up short – and medium-term inflation expectations. In the United States, core inflation rose by 5.9 per cent year-on-year in July, while in the euro area the index increased by 4 per cent, the highest rate since the common currency was introduced.

Inflation in many large developing economies has also accelerated and is now generally well above the comfort zone of the central banks. In Mexico, for example, annual inflation increased to 8.2 per cent in July 2022, the highest rate in more than 20 years. Similar upward trends are observed in Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Indonesia, and South Africa. The impact of rising living costs is much higher in the least developed countries with a large share of their population already living in poverty. The food crisis will likely increase the number of people living in extreme poverty.

Many central banks have been raising interest rates in quick succession in recent months, often opting for larger-than-usual rate hikes of 50 basis points or more to bring inflation under control and anchor inflation expectations. This shift towards tighter monetary policy is exceptionally broad-based (figure 4). About three out of four central banks worldwide have increased interest rates in 2022, reflecting the global nature of the current inflationary environment. The main exceptions to this trend are the People’s Bank of China, which reduced its key interest rates in January and August 2022 to support the economy, and the Bank of Japan, which has maintained its ultra-accommodative monetary stance, with negative short-term interest rates. Despite the recent hikes, however, real interest rates remain deep in negative territory.

Central banks in many developed countries are aiming at a “soft landing” for their economies, expecting to tame inflation without triggering a recession. The US Federal Reserve has taken a more aggressive stance than other major central banks, raising its key policy rate from 0–0.25 per cent in March to 2.25-2.5 per cent in August. By the end of 2022, the rate is projected to reach about 3.5 per cent, the highest level since 2008. The European Central Bank (ECB) raised its benchmark interest rates in July for the first time in more than a decade, ending an 8-year period of negative rates. Going forward, the ECB will face a difficult balancing act. While persistently high inflation calls for further rate hikes, there are significant downside risks to economic growth, including disruptions to gas supply and growing divergence of member States’ borrowing costs.

The Fed’s policy shift, coupled with a strong dollar, has further increased the pressure on central banks in developing countries to tighten monetary policy. In many cases, most notably in Latin America, central banks had already started raising interest rates in 2021, taking an increasingly aggressive tightening stance in 2022. However, monetary tightening, so far, has had only a very limited impact on inflation. This is mainly because the current bout of inflation is not primarily caused by excess demand, but rather by a combination of persistent supply shortages, rising international commodity prices, and downward pressure on national currencies. Central banks in developing countries are thus also facing difficult policy choices. Aggressive monetary tightening may do little to bring inflation down but could cause an economic downturn and undermine recovery from the pandemic. Overly loose monetary policy, on the other hand, may prolong inflationary pressures and increase the risks of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

The Fed’s policy shift, coupled with a strong dollar, has further increased the pressure on central banks in developing countries to tighten monetary policy. In many cases, most notably in Latin America, central banks had already started raising interest rates in 2021, taking an increasingly aggressive tightening stance in 2022. However, monetary tightening, so far, has had only a very limited impact on inflation. This is mainly because the current bout of inflation is not primarily caused by excess demand, but rather by a combination of persistent supply shortages, rising international commodity prices, and downward pressure on national currencies. Central banks in developing countries are thus also facing difficult policy choices. Aggressive monetary tightening may do little to bring inflation down but could cause an economic downturn and undermine recovery from the pandemic. Overly loose monetary policy, on the other hand, may prolong inflationary pressures and increase the risks of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

Rising borrowing costs and worsening liquidity conditions hit developing countries

Amid high inflation and aggressive policy rate hikes, financial conditions are tightening, borrowing costs are rising, and liquidity is shrinking. In developed countries, sovereign-bond yields have increased, while equity prices have declined amid spikes in volatility. Rising production costs and lower profit margins have also led to widening corporate bond spreads, with corporate bond yields surging to the highest levels since the global financial crisis. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the dollar has further appreciated against the euro, the yen, and the pound sterling as well as most developing country currencies.

Tighter monetary conditions and declining liquidity have raised the risks of disorderly adjustments in financial markets, with further declines in housing and asset prices in developed countries. With investors’ risk appetite falling, capital flows to emerging economies have declined markedly. Between February and July 2022, the 3-month moving average of capital flows fell from $11.2 to – $6.2 billion (figure 5). Bond issuance in the first quarter of 2022 was weaker than in any first quarter since 2016. Commodity-exporters from Latin America and Western Asia have seen more resilient flows, though.

Tightening fiscal space in developing countries: between a rock and a hard place

Tightening fiscal space in developing countries: between a rock and a hard place

The current global environment, with slowing economic growth, rapidly tightening global financial conditions and a soaring dollar, threatens to exacerbate fiscal and debt vulnerabilities in developing countries. Sovereign bond spreads have increased across developing countries in 2022 (figure 6), particularly among commodity-importers. The unprecedented measures taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis have helped prevent economic collapse and limit social damage but have left Governments with record levels of debt burdens and major fiscal challenges. Servicing the debt is becoming increasingly expensive, taking up an ever-growing share of revenues and constraining fiscal space. Also, tightening financial and capital market conditions are worsening “rollover” risks for many developing countries, pushing them towards debt defaults.

A growing number of developing countries find themselves in precarious debt situations. According to the IMF, 39 out of 69 low-income countries are now at high risk of or already in debt distress. Moreover, middle-income countries with market access also face mounting financial pressures. A record 21 emerging market sovereigns’ dollar bonds are trading at distressed levels – with yields more than 1,000 basis points (10 percentage points) above US treasuries of the same maturity. Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Zambia are already in default, after the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated long-standing debt problems. Several other countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, are at the brink of default. Even if the scenario of widespread debt distress and disorderly defaults does not materialize, heightened fiscal consolidation pressures threaten to trigger large cuts to public investment and social spending. This, in turn, would undermine economic recovery and cause further setbacks to sustainable development.

Multiple crises demand strengthened and more effective global cooperation

The pandemic, the global food and energy crisis, the ever-worsening climate catastrophe, and the looming debt crisis in developing countries are testing the limits of existing multilateral frameworks. Many countries have responded to new challenges and threats by adopting more inward-looking policies. Such reactions are misguided and short-sighted, however, as many of the current crises are global in nature and strongly interlinked. With an estimated 657 million people living in extreme poverty and the number of acute food-insecure people rising sharply, scaling-up international cooperation and development finance is critical at this juncture.

Official development assistance (ODA) from the Development Assistance Committee members remained at about 0.33 per cent of their combined gross national income in 2021, far below the 0.7 per cent target established by the General Assembly in 1970. Current levels of ODA remain inadequate for meeting the targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including those related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. To address the looming debt crisis in developing countries, bold, comprehensive, and forward-looking measures are needed. Existing mechanisms for highly indebted developing countries must be significantly improved and expanded.

Under the G20 ‘Debt Service Suspension Initiative’ (DSSI), which was established in May 2020 and ended in December 2021, bilateral official creditors suspended debt service payments from the poorest countries. By temporarily providing liquidity relief, the DSSI allowed countries to concentrate their resources on fighting the pandemic and mitigating the economic and social fallout. Overall, 48 out of 73 eligible countries participated in the initiative, which delivered an estimated total debt service suspension of $12.9 billion. While the DSSI offered breathing space, it did not address solvency problems as the amount of debt owed was not reduced (in other words, the suspension was net present value neutral). In addition, private creditors did not participate in the DSSI and middle-income countries were not eligible.

In view of these limitations, the G20 launched the ‘Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI’ in November 2020. This initiative aims to help the 73 DSSI-eligible countries deal with insolvency and protracted liquidity problems. When public debt is deemed not sustainable, the initiative can provide a deep debt restructuring, reducing the net present value of debt to restore sustainability. When debt is deemed sustainable, but liquidity issues exist, a portion of debt service payments can be deferred for several years to ease financing pressures. So far, however, only three countries—Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia—have requested debt relief under this framework and, in each case, the process has been very slow. This reflects difficulties in reaching agreement among official creditors (which include Paris Club members as well as China, India, and other countries) and in getting private creditors on board. Unlike in the DSSI, where private creditor participation was voluntary, the Common Framework requires private creditors to participate on comparable terms to overcome collective action challenges and ensure fair burden sharing. Moreover, some countries are reluctant to agree to an IMF-supported programme—a precondition to participating in the common framework—due to potentially strict austerity measures.

Even if the current shortcomings and obstacles of the Common Framework can be addressed, it is unclear if widespread debt crisis and fiscal crunch can be avoided. In many cases, the net present value of debt will need to be reduced swiftly and sharply. Otherwise, sovereign default or painful adjustments via cuts in development spending will only be delayed.

Follow Us