World Economic Situation And Prospects: September 2021 Briefing, No. 153

Is unconventional monetary policy reaching its limits?

Since the beginning of the twin public health and socioeconomic crises caused by COVID-19, central banks around the globe have implemented far-reaching monetary policies to calm panicky markets, stimulate economic activity, and boost inflation. Just like after the global financial crisis of 2007–08, unconventional monetary policy has played a crucial part in the response to COVID-19. Developed country central banks, for one, have purchased trillions worth of assets through their central banks’ quantitative easing (QE) programmes. But the pandemic has also marked a turning point for monetary policy among developing countries. For the first time ever, many developing countries have introduced unconventional monetary policy measures in the form of asset purchase programmes (APPs) by their central banks. While these programmes have been broadly modeled after unconventional monetary policy in developed economies, they have differed from conventional QE in both scope and purpose.

Despite successes in the early stages of the economic recovery, the stark expansion of APPs around the globe is no silver bullet. There are looming risks for both developed and developing economies. Just like the APPs themselves, the associated risks differ fundamentally. In developed economies, concerns have been primarily raised about QE’s impact on consumer prices, the formation of asset price bubbles, and rising wealth inequality. In developing countries, on the other hand, the core concern lies with impairing central banks’ institutional credibility, which could lead to future periods of increasing price instability.

Developed economies’ quantitative easing programmes

To address financial distress caused by the pandemic in early 2020 and to stimulate economic activity, developed economies’ central banks reacted quickly without straying too far from what had worked during the global financial crisis of 2007–08. They reduced policy rates to their effective lower bound and set expectations for prolonged low interest rates through forward guidance. To further boost investment and consumption, they also ramped up their asset purchases, causing balance sheets to balloon. Since the start of the pandemic, the central banks of Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and the euro area have added roughly $9.6 trillion in security assets to their balance sheets, letting their total assets soar to over $25.4 trillion (Figure 1).

What is central banks’ rationale behind enacting such massive APPs? In essence, QE works like an asset swap. Central banks purchase long-maturity securities, such as government bonds or mortgage-backed securities, from the financial system in exchange for short-term liquidity in the form of cash-equivalent bank reserves. The large-scale APPs reduce the security’s supply in the market, which drives up its price and causes the yields to drop. As a result, the additional liquidity is expected to enable banks to make more loans and the decline in government bond yields is thought to drive down the cost of substitutable long-term borrowing in the wider economy, ultimately boosting investment and consumption.

What is central banks’ rationale behind enacting such massive APPs? In essence, QE works like an asset swap. Central banks purchase long-maturity securities, such as government bonds or mortgage-backed securities, from the financial system in exchange for short-term liquidity in the form of cash-equivalent bank reserves. The large-scale APPs reduce the security’s supply in the market, which drives up its price and causes the yields to drop. As a result, the additional liquidity is expected to enable banks to make more loans and the decline in government bond yields is thought to drive down the cost of substitutable long-term borrowing in the wider economy, ultimately boosting investment and consumption.

The Fed is currently buying $120 billion worth of securities every month and has accumulated a total stock of $2.5 trillion in mortgage-backed securities and $5.3 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities.

The ECB’s APP continues at a monthly target pace of €20 billion, the lion’s share of which is earmarked for the public sector purchase programme under which national central banks buy their country’s government bonds. To further react to the economic fallout of the pandemic, the ECB also implemented a more flexible €1,850 billion pandemic emergency purchase programme, which includes all asset categories eligible under the APP.

Given vast differences in macroeconomic situations and policies, it is difficult to quantify the effects of QE. However, there is wide agreement that asset purchases have contributed to falling government bond yields (Figure 2). Bernanke (2020) recently estimated that in 2014 every $500 billion in QE lowered the 10-year treasury yield by 0.2 percentage points.3 If today’s transmission mechanism resembles the one from 2014, the Fed’s $1.8 trillion securities purchases in March and April 2020 alone could have caused a 0.72 percentage point reduction in the 10-year treasury yield, while the total $3.7 trillion in asset purchases since the start of the pandemic could have suppressed yields by as much as 1.5 percentage points. The effects in the euro area and Japan are likely lower, since QE’s effect on bond yields diminishes as long-term yields approach zero, which has been the case in both economies.

Given vast differences in macroeconomic situations and policies, it is difficult to quantify the effects of QE. However, there is wide agreement that asset purchases have contributed to falling government bond yields (Figure 2). Bernanke (2020) recently estimated that in 2014 every $500 billion in QE lowered the 10-year treasury yield by 0.2 percentage points.3 If today’s transmission mechanism resembles the one from 2014, the Fed’s $1.8 trillion securities purchases in March and April 2020 alone could have caused a 0.72 percentage point reduction in the 10-year treasury yield, while the total $3.7 trillion in asset purchases since the start of the pandemic could have suppressed yields by as much as 1.5 percentage points. The effects in the euro area and Japan are likely lower, since QE’s effect on bond yields diminishes as long-term yields approach zero, which has been the case in both economies.

Asset purchase programmes in developing economies

Developing economies, on the other hand, have faced a different set of monetary challenges during the initial crisis period and the recovery. Despite significant policy rate cuts since the onset of COVID-19, most central banks have been far from reaching the effective lower bound. This has given them sufficient policy space to stimulate economic activity through conventional monetary means. Nonetheless, several developing country central banks have embarked on asset purchases programs for the first time. Rather than providing monetary stimulus and further loosening financial conditions, these programs have primarily aimed at boosting market confidence and tackling market dysfunctionality. The measures were mainly introduced in response to the market turmoil in the early stages of the pandemic, when investor panic, rising risk premiums, and substantial capital outflows caused bond prices in developing countries to spike and currencies to depreciate (Figure 3).6 Reacting to these pressures, Indonesia was the first developing country to announce the start of a new APP programme in March 2020 (IMF, 2021a). Over the course of 2020, central banks in 22 developing economies – 9 in Africa, 7 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 6 in Asia – followed suit and introduced their own government bond purchasing programmes (IMF, 2021a).

APPs in developing countries have tended to be much smaller and more selective than programmes in developed economies. Total purchases have ranged from less than 1 per cent to 6 per cent of GDP, with most programmes in 2020 equivalent to less than 2 per cent (World Bank, 2021). These purchases have largely focused on public securities denominated in local currencies; however, some have also included private securities, bank bonds, or even equities, as has been the case in Egypt (IMF, 2021a).

APPs in developing countries have tended to be much smaller and more selective than programmes in developed economies. Total purchases have ranged from less than 1 per cent to 6 per cent of GDP, with most programmes in 2020 equivalent to less than 2 per cent (World Bank, 2021). These purchases have largely focused on public securities denominated in local currencies; however, some have also included private securities, bank bonds, or even equities, as has been the case in Egypt (IMF, 2021a).

The duration of programmes has also varied considerably. While asset purchases peaked in April 2020 in most cases, they have been scaled back at different rates. By the first quarter of 2021, India and Indonesia were the only major developing economies still engaged in significant asset purchases (IMF, 2021c). The majority of the countries conducting asset purchases has exclusively focused on secondary markets, but some have also resorted to purchasing bonds directly from the government. Central Banks in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Cabo Verde, Ghana, Indonesia, and Thailand all conducted APPs in primary markets, explicitly stating the support of fiscal needs as a reason (IMF, 2021a).

Costs and potential risks of unconventional monetary policy

Despite the expanding and widespread use of APPs around the world, there remains a heated debate whether the benefits of unconventional monetary policy in the form of large-scale asset purchases still outweigh the associated risks and costs for most countries.

On the one hand, APPs seem to have been relatively successful during times of severe financial distress and market dysfunction. During the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, developed country central banks’ massive asset purchases initially helped mitigate adverse feedback loops between financial markets and the real economy by providing liquidity and suppressing long-term yields. Similarly, APPs in developing countries appear to have contributed to stabilizing financial markets in the early stages of the pandemic. A recent World Bank (2021) study indicates that developing countries’ APPs have affected domestic bond yields more strongly than conventional policy rate cuts and developed economies’ QE programmes.

Still, APPs are no silver bullet. There is growing evidence that, beyond the immediate crisis period, QE programmes in developed economies have had only very limited impact on economic growth. Over time, the positive effects on output – through higher bank lending and investment – appear to have subsided. At the same time, the large-scale asset purchase programs entail significant distributional costs and macroeconomic risks.

First, the programs have contributed to an under-pricing of risk, driving up asset prices. On the bond market, the difference between privately owned gross U.S. federal debt’s average market value and its par value has increased by 4.6 percentage points between late 2019 and mid-2020. Increases in residential real estate prices have been even more pronounced: the Case-Shiller Home-price index for the United States had increased by 10.3 per cent year-on-year by the end of 2020. This upward trend in housing prices can also be observed globally, with nominal residential house prices rising by 5.6 per cent over the same period.

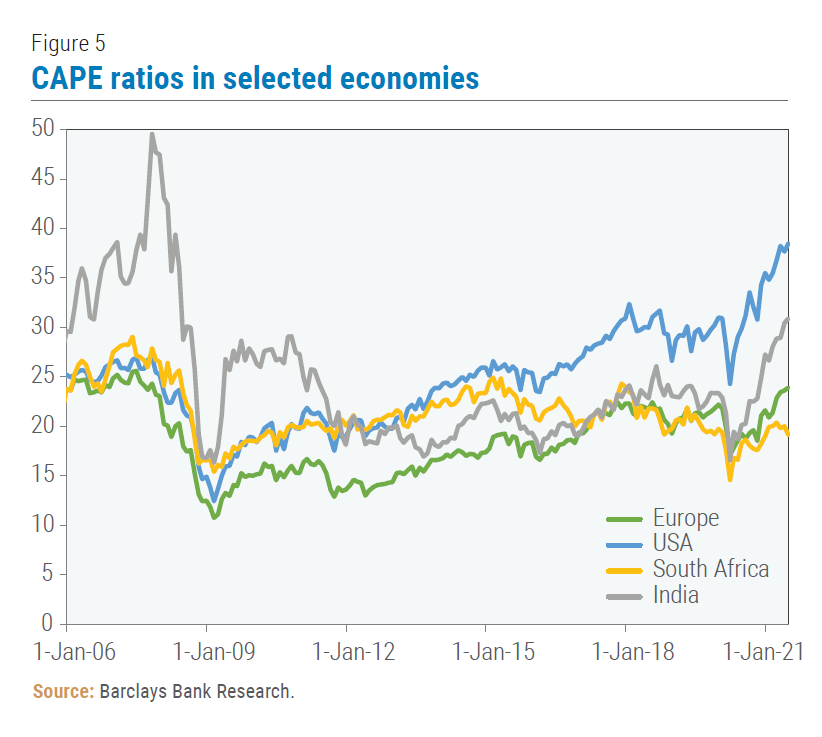

Lastly, equities have seen very strong price appreciations, breaking all-time high after all-time high. Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-earnings (CAPE) ratio for the Standard and Poor’s 500 index has increased by a staggering 12.1 points since April 2020 – more than after any other U.S. GDP trough in the past 120 years. As a result, U.S. equity markets have rarely been more expensive than they are now, and CAPE ratios are approaching levels only seen prior to the burst of the dot-com bubble (Figure 4). Equity prices have also rebounded in other countries, but valuations are generally lower than in the United States (Figure 5).

Lastly, equities have seen very strong price appreciations, breaking all-time high after all-time high. Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-earnings (CAPE) ratio for the Standard and Poor’s 500 index has increased by a staggering 12.1 points since April 2020 – more than after any other U.S. GDP trough in the past 120 years. As a result, U.S. equity markets have rarely been more expensive than they are now, and CAPE ratios are approaching levels only seen prior to the burst of the dot-com bubble (Figure 4). Equity prices have also rebounded in other countries, but valuations are generally lower than in the United States (Figure 5).

These strong price increases have spurred fears of a formation of asset price bubbles amid a growing disconnect between financial markets and the real economy. A bursting of asset price bubbles could result in a rising number of bankruptcies and undermine the still fragile global economic recovery.

This risk is particularly pronounced in developed economies where asset purchases have been largest and prices have risen most sharply. However, even in some developing countries with far smaller APPs – in absolute and relative terms – the formation of asset bubbles could be a concern as market capitalizations are much smaller. Moreover, the spillover effects from QE in developed economies have been substantial. According to World Bank (2021) estimates, equity markets in developing countries were more affected by developed countries’ QE programmes than by the domestic APPs.

Another macroeconomic risk lies in the institutional credibility of central banks. APPs may do more harm than good if they de-anchor inflation expectations or weaken exchange rates. These risks are more pronounced for central banks with lower institutional credibility – particularly so in countries with weak economic fundamentals. Early research among developing countries further indicates that APPs by central banks with high levels of institutional credibility were more successful in calming stress in the bond market (IMF, 2020). If central banks impair their credibility, future interventions might prove less effective.

Another macroeconomic risk lies in the institutional credibility of central banks. APPs may do more harm than good if they de-anchor inflation expectations or weaken exchange rates. These risks are more pronounced for central banks with lower institutional credibility – particularly so in countries with weak economic fundamentals. Early research among developing countries further indicates that APPs by central banks with high levels of institutional credibility were more successful in calming stress in the bond market (IMF, 2020). If central banks impair their credibility, future interventions might prove less effective.

Secondly, APPs also have significant distributional costs. Between the fourth quarters of 2019 and 2020, the top 1 per cent wealthiest U.S. citizens averaged net-wealth-gains of over $1.5 million, while the bottom 50 per cent recorded only a gain of $2,234. In part, this divergence reflects pre-existing wealth inequalities, but total assets of the top 1 per cent have grown nearly twice as fast as assets held by the bottom 50 per cent. This trend is not unique to the United States, although it is generally less pronounced in other countries.

Differing degrees of risk aversion in different segments of the population are one driver of this effect. Returns on safe assets have remained depressed and are generally negative in real terms. This has pushed investors into riskier assets such as equities or alternative investments, which have seen unprecedented price increases. As a result, risk averse savers who invest primarily in fixed income assets – especially bank savings – have generally been worse off than investors with a strong risk appetite. Low interest rates in the real economy also have significant distributional implications across the borrower-saver dimension. New homeowners are particularly benefitting from low interest rates on mortgage loans and fast appreciation rates of their highly leveraged investment in the residential housing market. Despite a global upward trend in housing prices, benefits are often skewed towards higher-income earners, which have experienced the strongest price increases.

In sum, focused unconventional monetary policy may have a role to play in the future crisis-toolkit of countries with credible monetary policy frameworks and good governance. However, central banks should be wary of the costs from large-scale APPs. During more normal economic circumstances, where the benefits of asset purchases are less pronounced, central banks would do well to recognize the distributional consequences and structural risks of these programs.

Follow Us