World Economic Situation And Prospects: October 2020 Briefing, No. 142

Public finances after COVID-19: is a high-debt, low-growth trap looming for developing countries?

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered unprecedented policy responses around the world. Governments of developed and developing countries have taken extraordinary steps to halt the spread of the virus and limit the economic and social fallout from the crisis. In the face of rapidly declining private sector demand, public support in the form of monetary and fiscal stimulus has been vital to avert economic collapse. However, the massive interventions have left governments with record debt burdens and major fiscal challenges going forward.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered unprecedented policy responses around the world. Governments of developed and developing countries have taken extraordinary steps to halt the spread of the virus and limit the economic and social fallout from the crisis. In the face of rapidly declining private sector demand, public support in the form of monetary and fiscal stimulus has been vital to avert economic collapse. However, the massive interventions have left governments with record debt burdens and major fiscal challenges going forward.

The situation is especially precarious among developing countries, where a growing number of economies face the risk of catastrophic sovereign debt crisis. Even if the most dire scenario of widespread debt distress and disorderly defaults does not materialize, the looming fiscal squeeze—i.e. the effort to correct public finances through a combination of higher taxes and lower spending—could severely undermine countries’ prospects of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. As debt levels and debt servicing burdens rise, many developing country governments will be confronted with large and persistent fiscal adjustment needs. This could force them to cut investment in critical areas of development, such as health, education, physical and digital infrastructure, technology, and the energy transition. With growth prospects already weighed down by significant crisis legacies, a further hit to productive capacities and social services could have devastating economic, social and, possibly, political consequences. While multilateral responses have so far focused on low-income countries, risks of debt distress and pressures for large-scale fiscal consolidation affect a wide range of developing countries at all income levels and across all major regions. Hence, international solutions to the rising debt challenges must be comprehensive and inclusive, adopting a long-term perspective on sovereign debt sustainability and financing needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown the public finances of developing countries into disarray

For many developing countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a perfect storm for public finances. The crisis has undermined economic activity and affected both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget. Emergency measures to support the health sector and cushion the effect of the crisis on households and firms have caused government expenditures to rise. At the same time, tax revenues have fallen sharply due to the economic slowdown, the lower commodity prices, and the administrative measures (e.g., temporary tax breaks and tax deferrals) taken in response to the crisis. As a result, key fiscal metrics—such as the primary government deficit (before interest payments) and the debt-to-GDP ratio—are projected to deteriorate significantly in 2020. How large the downward revisions will be is not yet clear as countries’ fiscal outlooks are evolving with the pandemic and are subject to much greater uncertainty than usual.

While the availability of high-frequency fiscal data for developing countries is limited, recent updates from several economies that have been severely affected by the pandemic paint a gloomy picture. In Brazil, for example, central government expenditures increased by 40.3 per cent in real terms during the first half of 2020 from a year ago, whereas total revenues declined by 16.5 per cent. Treasury authorities expect a primary budget deficit of about 11 per cent of GDP and an overall fiscal deficit of 18 per cent of GDP. Accordingly, Brazil’s gross government debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to jump from 76 per cent in 2019 to about 95 per cent in 2020. In South Africa, the Government projects that the budget deficit for the current fiscal year will widen to 15 per cent of GDP. Government debt is expected to reach 80 per cent of GDP, three times the rate recorded in 2008.

Based on the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) April 2020 Fiscal Monitor, the overwhelming majority of developing economies will face massive budget shortfalls this year. Whereas no country is immune to the pandemic’s fiscal damage, fuel exporters and tourism-dependent countries, including many Small Island Developing States (SIDS), are among those hardest hit. The budgets of oil exporters have been battered by the collapse in oil prices during the early stages of the pandemic. Even though prices have climbed back from their lows in April, they are unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels any time soon. During the first eight months of 2020, the average price of Brent crude was 35 per cent lower than a year ago. As a result, fiscal deficits are projected to soar in countries where oil revenues are the dominant source of government income, such as Algeria, Brunei Darussalam, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Meanwhile, tourism-dependent economies are struggling with ongoing international travel restrictions and travel-wary consumers. In the first half of 2020, international tourism arrivals fell by 65 per cent compared to the same period last year. With their main source of income collapsing, many tourism-dependent economies are expected to see large financing gaps. In countries such as the Bahamas, Fiji, Kiribati, and the Maldives, the fiscal deficit is expected to reach double-digits as a share of GDP. In the absence of a widely distributed vaccine, the recovery prospects of tourism-dependent countries remain highly uncertain.

Fiscal vulnerabilities have been building for over a decade

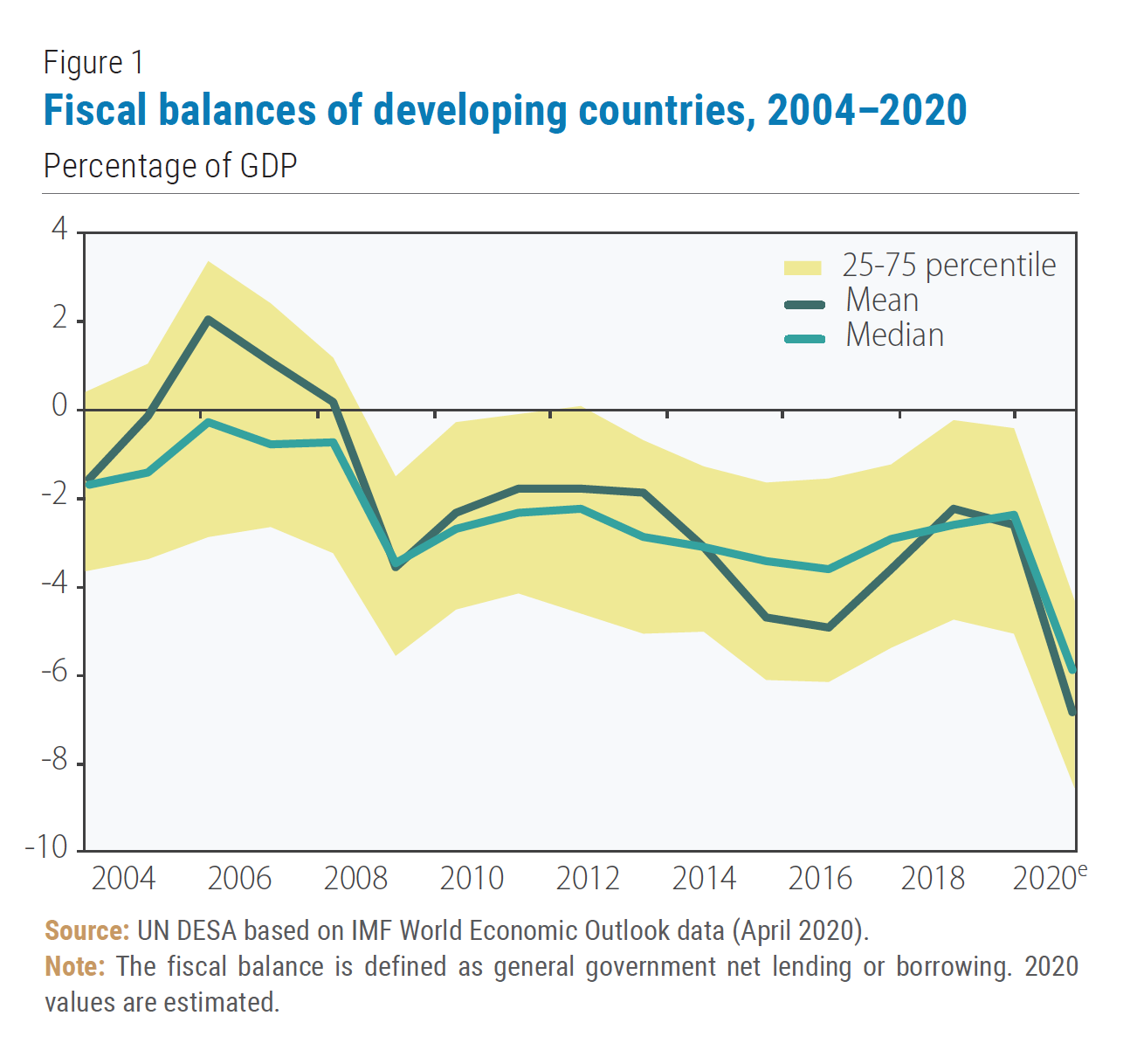

What makes the current situation so ominous is that in a large number of cases the pandemic has aggravated an already weak fiscal position. In fact, fiscal vulnerabilities in developing countries have been building for some time. For many countries, the COVID-19 crisis constitutes the third major shock to public finances in just over a decade. As shown in figure 1, the fiscal balances of developing countries deteriorated sharply in the wake of the 2008–09 global financial crisis, during the 2014–16 commodity price downturn, and now again in 2020. During the economic upswings that followed the former two crises, government budgets never fully recovered and generally remained in deficit. As a result, almost four out of five developing countries entered the COVID-19 crisis with a fiscal deficit.

What makes the current situation so ominous is that in a large number of cases the pandemic has aggravated an already weak fiscal position. In fact, fiscal vulnerabilities in developing countries have been building for some time. For many countries, the COVID-19 crisis constitutes the third major shock to public finances in just over a decade. As shown in figure 1, the fiscal balances of developing countries deteriorated sharply in the wake of the 2008–09 global financial crisis, during the 2014–16 commodity price downturn, and now again in 2020. During the economic upswings that followed the former two crises, government budgets never fully recovered and generally remained in deficit. As a result, almost four out of five developing countries entered the COVID-19 crisis with a fiscal deficit.

The deterioration in developing countries’ fiscal positions since the mid-2000s can also be seen in figure 2, which decomposes the overall fiscal balance into the primary balance and interest payments. On average, developing countries have been running a primary fiscal deficit in every year since 2009. At the same time, the interest burden has risen steadily over the past decade. In 2020, average interest payments are projected to account for about 2 per cent of GDP and 12 per cent of government revenues, the highest levels since 2002. Moreover, these aggregate figures mask much more alarming trends at the individual country level. In about a dozen countries—including several with very large populations such as Brazil, Nigeria and Pakistan—governments are expected to spend at least a quarter of total revenues on interest payments this year.

The observed increase in the interest burden is due to a steadily rising public debt stock rather than higher average interest rates. In fact, the median developing country government pays a slightly lower nominal effective interest rate on its debt today than before the global financial crisis. While the average rate has been hovering around 4 per cent in recent years, there are large differences across countries. In 2019, the nominal effective interest rate on public debt exceeded 7 per cent in 18 of the countries in the sample, including Brazil, Egypt, Ghana, India, Kenya, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey.

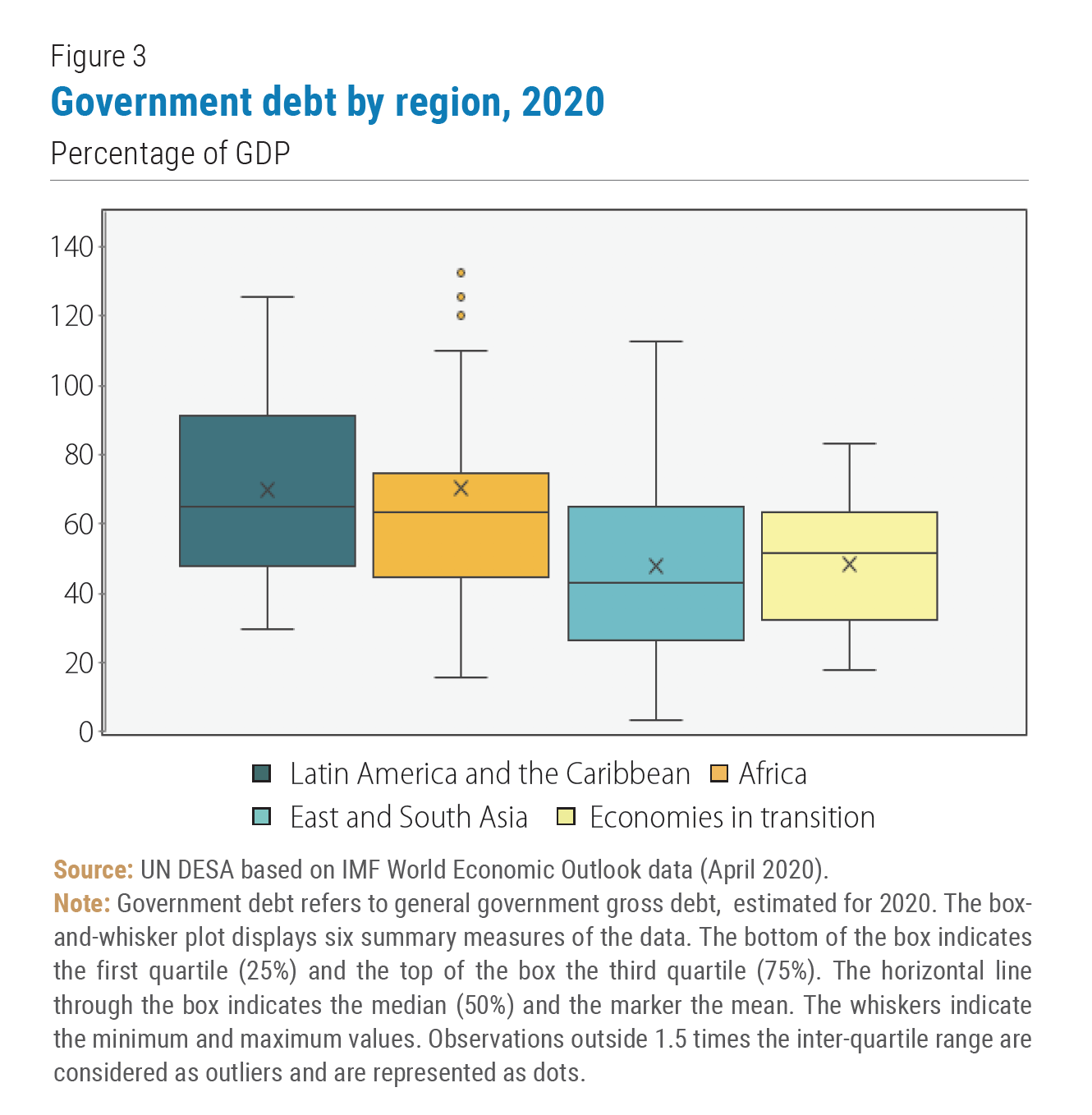

With most developing countries running persistent fiscal deficits since the global financial crisis, public debt levels have increased drastically. The median government debt-to-GDP ratio in the sample is projected to reach 58 per cent in 2020. This is almost twice as high as in 2007 and the highest level since the multilateral debt relief programs of the early 2000s. Public debt challenges are particularly large in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, where the median government debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to exceed 60 per cent (figure 3). Among the most indebted economies are a number of least developed countries (LDCs) in Africa as well as several Caribbean SIDS, where the pandemic has undermined long-standing debt reduction efforts.

Presumably, developing country governments have gained some degree of protection from their ability to tap into local currency debt markets in recent decades. In fact, the phenomenon known as “original sin”—the lack of development of the local currency debt markets relative to those in foreign currency—has diminished over time. However, foreign currency-denominated debt often still accounts for a large portion of overall debt. According to the latest data from the World Bank’s Quarterly Public Sector Debt database, the share is above 50 per cent in countries such as the Dominican Republic, Kenya, Mongolia, Rwanda, Sri Lanka and Uganda. Moreover, domestic currency debt is not as safe as previously thought. In fact, amid increased recognition that sovereigns also default in domestic currency, the difference in the level of local versus foreign currency risk has steadily decreased over time.

Presumably, developing country governments have gained some degree of protection from their ability to tap into local currency debt markets in recent decades. In fact, the phenomenon known as “original sin”—the lack of development of the local currency debt markets relative to those in foreign currency—has diminished over time. However, foreign currency-denominated debt often still accounts for a large portion of overall debt. According to the latest data from the World Bank’s Quarterly Public Sector Debt database, the share is above 50 per cent in countries such as the Dominican Republic, Kenya, Mongolia, Rwanda, Sri Lanka and Uganda. Moreover, domestic currency debt is not as safe as previously thought. In fact, amid increased recognition that sovereigns also default in domestic currency, the difference in the level of local versus foreign currency risk has steadily decreased over time.

Sovereign default risks have risen, and so has the possibility of protracted fiscal paralysis

Clearly, the debt crisis that is now looming across developing countries has been long in the making. With fiscal vulnerabilities building for over a decade, it comes as little surprise that the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis have been pushing more and more countries to the brink of default. According to the latest debt sustainability analysis by the IMF and the World Bank, 36 low-income countries are either already in debt distress or at a high risk thereof. At the same time, sovereign debt downgrades by the major credit rating agencies have soared in 2020, reaching the highest level in 40 years. Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia have defaulted on their sovereign debt and are at different stages of the restructuring process.

COVID-19 has not only plunged many developing countries into deep recessions, but, similar to past crises, will also likely inflict longer-lasting damage to economies. Several central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of India, have already warned against a structural downward shift in potential output due to the pandemic. As bankruptcies rise, private investment is likely to remain weak, stifling innovation and productivity growth. At the same time, prolonged school closures and rising unemployment are expected to adversely affect human capital accumulation, exacerbating existing skills shortages. An increasingly fragmented and uncertain global trade environment, amid heightened opposition to globalization, could further reduce developing countries’ growth potential. For many countries, especially in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, a decline in potential output would come on top of an already anaemic growth performance in recent years. Since 2015, Africa’s GDP is estimated to have grown by a mere 2 per cent per year, well below the rate of population growth. During the same period, the GDP of Latin America and the Caribbean contracted at an average annual rate of 0.5 per cent.

Against this backdrop, the current fiscal situation of developing countries looks particularly worrisome. On the one hand, the risk of a devastating debt crisis has risen for many countries. A disorderly default could trigger a deep recession and require painful adjustment. On the other hand, there is the danger of protracted fiscal paralysis that would further weaken growth prospects and hinder countries’ capacity to achieve sustainable development objectives. In fact, a large number of developing economies are at risk of becoming trapped in a vicious cycle of high debt and low growth. In the aftermath of the pandemic, governments may be forced to devote an ever-increasing share of their resources to servicing the debt. Heightened fiscal consolidation pressures could trigger large cuts to public investment and social spending. This, in turn, would further depress economic growth and undermine political stability, making the debt burden even harder to bear.

Bolder, more comprehensive and forward-looking global measures are needed

Such a negative, self-perpetuating cycle can only be broken if countries manage to return to more robust and sustained economic growth. Hence, any international response must aim to ensure that developing countries can expand fiscal space and grow out of their debt problems. In this light, the initiatives that have so far been undertaken by the international community can only serve as a first step. While debt standstills have provided some breathing room to many developing countries, they do not address any of the underlying systemic issues. The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which allows 77 International Development Association (IDA) countries and LDCs to suspend principal and interest payments on their debts to G20 countries until the end of 2020, is limited in scope. Although a large part of debt is owed to private creditors, the standstill only applies to official bilateral debt. The expected savings generated in 2020 will generally be small compared to the needs of eligible countries. Worse still, the initiative is supposed to be neutral in net present value terms, requiring recipients to fully repay the postponed debt service in the coming years. Accordingly, recipient country governments would face higher interest payments and increased budgetary pressure going forward, further reducing the resources available to invest in sustainable development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and aggravated the debt vulnerabilities of many developing countries. Without bolder, more comprehensive and more forward-looking measures, the current situation could develop into a protracted crisis, with devastating consequences for poverty reduction and, more broadly, sustainable development. Concrete solutions will have to be based on certain key principles. First, premature moves to fiscal austerity need to be avoided at all costs as they would further weaken the economies and, as a result, hinder repayment capacity. Second, for a large number of developing countries, the net present value of debt needs to be reduced through comprehensive debt restructuring. Otherwise, a debt crisis or severe cuts in development spending will only be delayed. Third, initiatives to reduce the debt burden must be long term and open to all developing countries. Fourth, participation of private creditors is essential. This will require the use of incentives and statutory measures, founded on collaboration between creditor and debtor countries. And fifth, repayment schedules will need to be based upon and adjusted to actual growth performances of countries. Debtor countries first need to return to robust growth before substantial debt repayment can be on the table.

Follow Us