World Economic Situation and Prospects: May 2022 Briefing, No. 160

Rising inflation hits developing countries

Global inflation is rising substantially, driven by higher energy and food prices, persistent supply chain disruptions, and tight labor markets in major developed economies. In the United States, inflation has reached multi-decade highs in recent months, prompting the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and initiate a global monetary tightening cycle. Rising inflation in the developed economies has received considerable attention.

Global inflation is rising substantially, driven by higher energy and food prices, persistent supply chain disruptions, and tight labor markets in major developed economies. In the United States, inflation has reached multi-decade highs in recent months, prompting the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and initiate a global monetary tightening cycle. Rising inflation in the developed economies has received considerable attention.

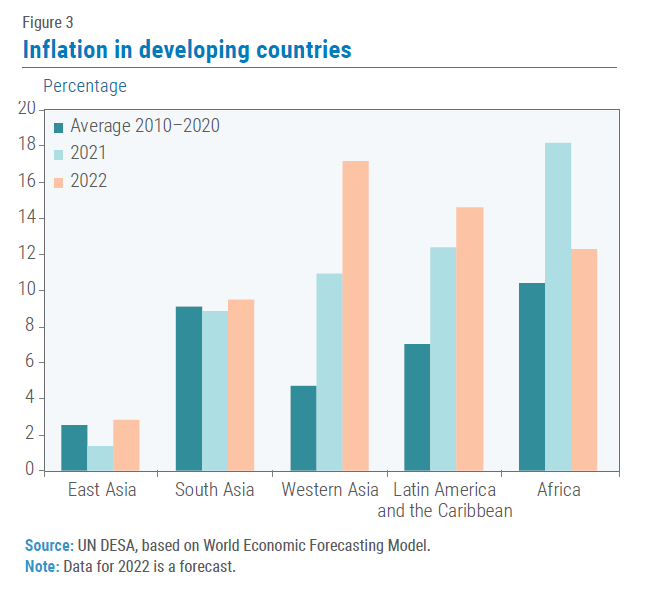

At the same time, inflation in developing countries – generally higher and more volatile than in developed countries – is also rising markedly and becoming more widespread as well. The return of inflation as a more prevalent phenomenon in developing countries marks a major turning point in macroeconomic conditions, creating greater challenges for policymakers. Over the past few decades, inflation in developing countries has generally been on a downward trend, thanks to demographic changes, technology-driven efficiency gains and improved macroeconomic policies, including more credible monetary policy frameworks. While inflation in developing countries was on average well above 10 per cent between 1990–2000, it fell to 5.6 per cent between 2001–2010 and 4.8 per cent between 2011–2020. In 2021, inflation surged to 6.3 per cent and is projected to rise substantially further in 2022 (figure 1).

The rise in inflation comes at exceptionally challenging times as many developing countries are still struggling to recover from the pandemic. For a large number of countries, a significant slack in domestic labor markets remain, and poverty levels are much higher compared to 2019. Debt levels have increased significantly, leading to a higher risk of debt distress. Moreover, faster-than-expected monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve could generate adverse spillovers. As previous episodes of high inflation illustrate, a deterioration in global financing conditions could trigger significant capital flow outflows and severe depreciation of domestic currencies in developing countries, fueling inflation further. Against this backdrop, central banks face difficult policy trade-offs in efforts to contain the rise of inflation while supporting a fragile economic recovery and preserving financial stability.

The return of inflation to the developing world

Inflationary pressures first began to spread out through 2021, particularly in Africa, Western Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean. In these regions, headline inflation figures reached double-digits due to rising oil and food prices (figure 2), supply chain disruptions, and depreciation of domestic currencies. For example, Argentina, Chile, Nigeria, Lebanon, and Turkey faced significant depreciation pressures throughout 2021. Inflation in sub-Saharan Africa was mainly driven by higher food prices, particularly wheat, corn, and sorghum. In Latin America, inflationary pressures became broader due to the accommodative monetary stances that remained in most countries as part of the pandemic response, wage indexation and, in some cases, strong aggregate demand. In Chile, for example, pandemic-related support, together with pension withdrawals, boosted consumer spending considerably, fueling inflationary pressures. In Brazil, headline inflation surged mainly due to higher oil and commodity prices, reaching 10.3 per cent in December 2021 (figure 3). Meanwhile, inflation in South Asia remained relatively elevated but not rising further. By contrast, inflationary pressures were muted in East Asia, including China.

Global inflationary pressures have intensified in recent months. The war in Ukraine and the sanctions against the Russian Federation have pushed oil and food prices to record highs, while worsening supply chain disruptions and shipping bottlenecks. In addition, China’s rolling lockdowns to control COVID-19 are aggravating global supply chain problems. By March 2022, supply chain disruptions in China were close to record highs.

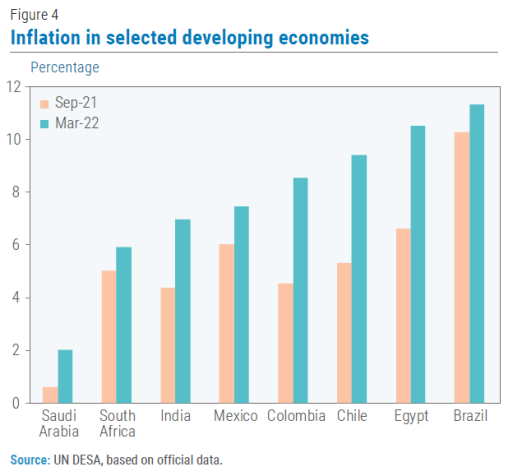

Inflationary pressures are becoming more entrenched across the developing world, with inflation in many large developing economies accelerating considerably in recent months (figure 4). In Egypt, annual inflation increased from 6.6 per cent in September 2021 to 10.5 per cent in March 2022, while in India it increased from 4.4 per cent to 7.0 per cent. A similar upward trend has been observed in Saudi Arabia, Colombia, Mexico, and South Africa. Notably, the rise in inflation is not constrained to headline numbers, which include volatile energy and food prices. Even core inflation (which excludes food and energy price and is considered indicative of the broad underlying trend in price levels) is rising significantly in many countries, including Brazil, Egypt, and Turkey, and it remains elevated in Argentina and Nigeria. Furthermore, the rise in inflation is not only limited to large developing economies but also affecting many others, including some least developed and low-income countries. In the last six months, headline inflation figures increased – or remains elevated – in Angola, Burundi, Ethiopia, Mongolia, and Sri Lanka, among others.

The rise in global commodity prices is particularly hurting poor households as they spend a much larger share of their income on food items. The sharp increase in food prices risks pushing millions more into poverty, while exacerbating inequality even further. Worryingly, surging food inflation could worsen food insecurity in many developing countries that are still struggling with economic shocks from the pandemic. Higher food prices are hitting the most vulnerable in challenging times. Labor markets remain with a substantial slack, including lower employment and higher unemployment rates than pre-pandemic levels in many countries across Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean.

Amid a relatively weak and fragile recovery and limited macroeconomic policy space, the rise in inflation will constrain many countries’ capacity to reduce poverty rates, further pushing back prospects of achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of ending extreme poverty. Furthermore, if inflation remains elevated, poverty rates will not decline to pre-pandemic levels anytime soon. Against this backdrop, the risks of social unrest and political instabilities across developing countries are rising.

Putting the genie back in the bottle?

In 2021, as oil and food prices increased steadily, prospects of inflation and of the Federal Reserve unwinding its monetary support led to a few central banks raising their interest rates. The central bank of Brazil was among the forerunners, embracing monetary tightening as early as March 2021. Over time, it increased its Selic rate in stages to 11.75 in March 2022. By mid-2021, other central banks gradually started to raise their interest rates as well. While inflationary pressures were a major reason, the rise in interest rates ahead of the Federal Reserve – especially in countries more integrated to global financial markets like Chile, Mexico, and South Africa – sought to contain potential capital outflows and depreciation pressures, too.

Since the second half of 2021, the monetary tightening in developing countries gained further momentum (figure 5). Between January and April 2022, at least 27 central banks decided to increase their policy rates, especially in Latin America (Argentina, Peru, Chile, and Uruguay) and Africa (Egypt, South Africa). Given the relatively contained inflation numbers – partly due to more muted increases of rice prices – central banks in East Asia have remained more passive, at least for now. The People’s Bank of China decided to even cut its loan prime rate last January, in efforts to boost domestic demand. Despite rising inflation numbers, India’s central bank has maintained its policy rates unchanged, prioritizing economic activity and the recovery of employment.

Since the second half of 2021, the monetary tightening in developing countries gained further momentum (figure 5). Between January and April 2022, at least 27 central banks decided to increase their policy rates, especially in Latin America (Argentina, Peru, Chile, and Uruguay) and Africa (Egypt, South Africa). Given the relatively contained inflation numbers – partly due to more muted increases of rice prices – central banks in East Asia have remained more passive, at least for now. The People’s Bank of China decided to even cut its loan prime rate last January, in efforts to boost domestic demand. Despite rising inflation numbers, India’s central bank has maintained its policy rates unchanged, prioritizing economic activity and the recovery of employment.

So far, higher interest rates in developing economies have had little success in curbing inflation rates, due to the nature and size of the underlying forces. Inflationary pressures have been driven mainly by supply side factors, including production shortages, supply chain disruptions, and shipping bottlenecks. Central banks are not well-equipped to deal with those supply side shocks, many of which are structural in nature. In addition, there is a considerable lag for higher rates to curb consumer spending in those countries where aggregate demand plays. Moreover, inflationary pressures seem to gradually become more persistent. For instance, commodity prices are projected to remain elevated throughout 2022, amid ongoing conflict in Ukraine. Also, lower fertilizer exports from the Russian Federation might result in lower crop yields globally over several successive growing seasons. These supply side disruptions are not projected to subside anytime soon. The rolling lockdowns in a number of cities in China, including major manufacturing centers and port cities, is likely to exacerbate the shortage of semiconductors. As such, inflationary pressures will likely not lessen significantly in the near term.

The spectre of high inflation poses major policy challenges for developing countries, well beyond inflation and growth trade-offs. On the one hand, aggressive interest rate hikes can derail the recovery and worsen employment prospects even further. In addition, rising interest rates will further limit fiscal space and worsen debt sustainability risks, especially in many already vulnerable countries, potentially leading to a widespread debt crisis. On the other hand, a relatively loose monetary approach could lead to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations and a further surge in inflation, severely impacting consumer spending, investment, and growth in the medium-term. Considering past episodes, this remains a key risk, for example, for countries in Latin America, where rising prices can feed into an escalation of inflation expectations and lead to a spiraling increase of wages and prices.

Furthermore, adequate implementation of monetary and fiscal policies should carefully consider the tightening global monetary conditions. Net oil and food importing countries are more at risk of facing intensified pressures to their balance of payment and fiscal positions. Monetary policy requires careful calibration, credible frameworks, and clear communication. On the fiscal side, Governments, with adequate fiscal space, will need to provide targeted support to alleviate the effects of higher food and fuel prices to poorer segments of the population, while maintaining fiscal and debt sustainability. This reinforces the recent and widespread calls to accelerate the debt relief for the poorer countries, particularly the least developed countries.

Follow Us