World Economic Situation And Prospects: May 2021 Briefing, No. 149

Emerging inflationary pressures and policy dilemma

Emerging inflationary pressures and policy dilemma

Since the beginning of 2021, the world economy has been facing emerging upward inflationary pressures. For several countries, price dynamics became more worrying. By April, central banks in Belarus, Brazil, Georgia, Russian Federation, Turkey and Ukraine hiked policy interest rates, tightening policy stance to contain surging consumer prices. In the United States, policy debates on inflation are back. Some critics argued that the $1.9 trillion stimulus package rolled out in March will intensify inflationary pressures. While the policymakers in the United States are monitoring inflation closely, global financial markets are already factoring in the prospects of higher inflation.

This Monthly Briefing reviews several factors contributing to emerging inflationary pressures, taking into account the price dynamics in the oil market, grains market, base metal market, semiconductor chip shortage, international shipping, labour market, and monetary factors. It also reviews the price dynamics in Brazil to highlight a policy dilemma that policymakers may face in 2021. It concludes that the combination of rising agricultural commodity prices and currency depreciation present the risk of higher food price inflation in many developing countries, which will exacerbate poverty levels even further.

The inflation episode of 2007–2008

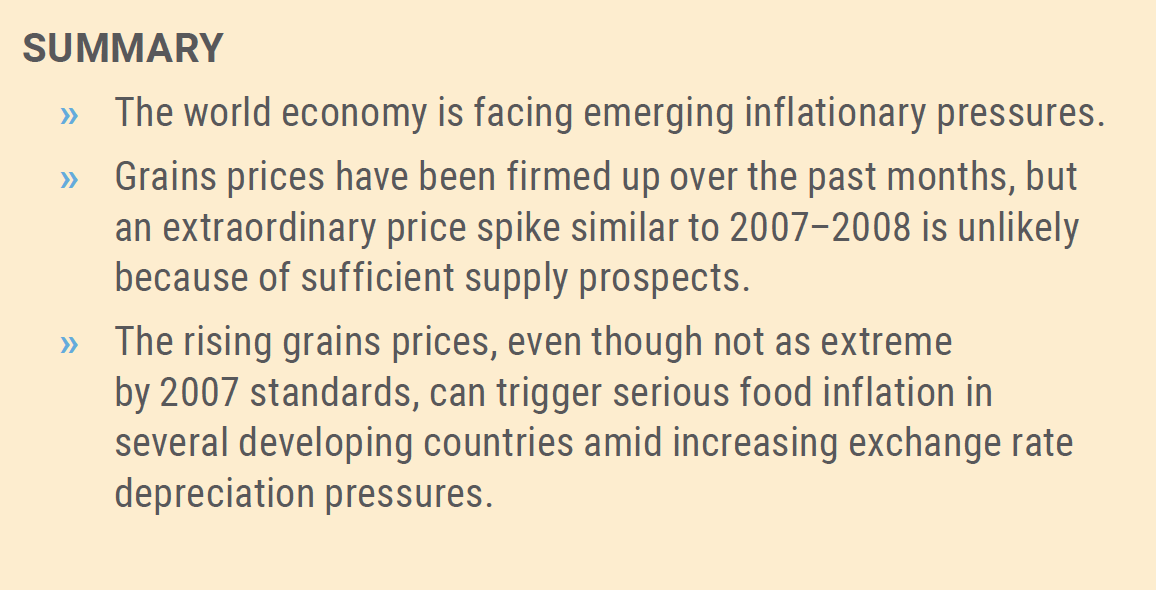

As a global trend, inflation has come down over the last three decades (figure 1). The last time the world economy faced significant inflationary pressures was in 2007 through the first half of 2008. The world average inflation rate reached 8.9 per cent in 2008, before plunging to 2.6 per cent over the last decade. The primary contributing factor for the inflation from 2007 to 2008 was a rapid surge of international commodity prices. The hike in oil prices was accelerated due to a robust demand forecast, outstripping the rigid supply capacity. The price of wheat rose on the weak production forecast for the 2007/8 season after a severe drought reduced wheat production substantially in Australia, the European Union, and the United States in the 2006/7 season. Rice production also stagnated, and rice prices shot up after several leading producers banned rice exports to increase supply against domestic shortages. International commodity prices also became the target of financial speculators seeking an alternative investment class as the share prices started stagnating in early 2008. The price of Brent crude oil hit a historic high at $143 per barrel in July 2008, rising by 73 per cent from July 2007. The prices of grains peaked earlier that year. The price of rice registered a 215 per cent year-on-year hike in April, and the price of wheat rose by 133 per cent a year to March. The steep increase of those essential items created considerable inflationary pressures on both developed and developing countries.

As a global trend, inflation has come down over the last three decades (figure 1). The last time the world economy faced significant inflationary pressures was in 2007 through the first half of 2008. The world average inflation rate reached 8.9 per cent in 2008, before plunging to 2.6 per cent over the last decade. The primary contributing factor for the inflation from 2007 to 2008 was a rapid surge of international commodity prices. The hike in oil prices was accelerated due to a robust demand forecast, outstripping the rigid supply capacity. The price of wheat rose on the weak production forecast for the 2007/8 season after a severe drought reduced wheat production substantially in Australia, the European Union, and the United States in the 2006/7 season. Rice production also stagnated, and rice prices shot up after several leading producers banned rice exports to increase supply against domestic shortages. International commodity prices also became the target of financial speculators seeking an alternative investment class as the share prices started stagnating in early 2008. The price of Brent crude oil hit a historic high at $143 per barrel in July 2008, rising by 73 per cent from July 2007. The prices of grains peaked earlier that year. The price of rice registered a 215 per cent year-on-year hike in April, and the price of wheat rose by 133 per cent a year to March. The steep increase of those essential items created considerable inflationary pressures on both developed and developing countries.

Contributing factors to emerging inflationary pressures

Several contributing factors need to be reviewed to look into currently emerging inflationary pressures, including the oil market, grains market, base metal market, semiconductor chip shortage, international shipping, wages and monetary factors.

Oil market

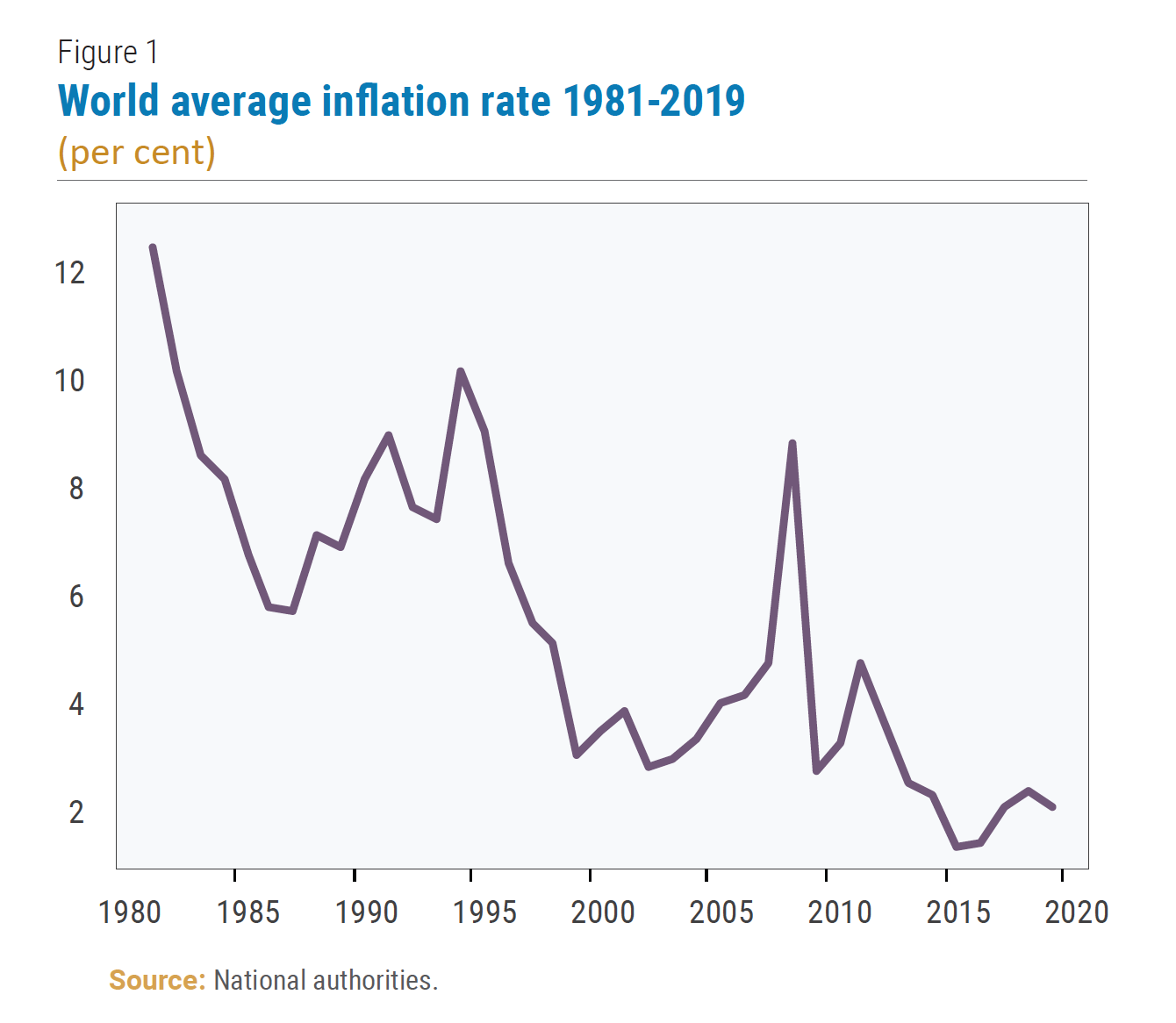

By April 2021, oil prices have gradually recovered after a steep plunge in 2020. The current price level, $65 in Brent, is slightly higher than the average over 2019 (figure 2). As opposed to the market situation in 2008 when the supply capacity was severely limited, the excess supply capacity of crude oil producers is abundant at present. The OPEC, Russian Federation and other crude oil-producing countries, known as the OPEC Plus, had cut the output by 9.7 million barrels per day in May 2020 and increased the output only gradually. As of March, the world crude oil production stood at 93.2 million barrels per day, 6 per cent lower than the 2019 average. However, even if Brent crude oil prices are stabilized around $60, it produces extraordinarily high year-on-year growth values due to the base effect. For example, the year-on-year growth of Brent crude oil is expected to be 240 per cent in April. Those values are calculated against extremely low bases of $18 per barrel in April 2020. Therefore, these values must be interpreted carefully. The rising oil prices create a certain level of inflationary pressures, but it is much milder than what those year-on-year growth figures suggest.

By April 2021, oil prices have gradually recovered after a steep plunge in 2020. The current price level, $65 in Brent, is slightly higher than the average over 2019 (figure 2). As opposed to the market situation in 2008 when the supply capacity was severely limited, the excess supply capacity of crude oil producers is abundant at present. The OPEC, Russian Federation and other crude oil-producing countries, known as the OPEC Plus, had cut the output by 9.7 million barrels per day in May 2020 and increased the output only gradually. As of March, the world crude oil production stood at 93.2 million barrels per day, 6 per cent lower than the 2019 average. However, even if Brent crude oil prices are stabilized around $60, it produces extraordinarily high year-on-year growth values due to the base effect. For example, the year-on-year growth of Brent crude oil is expected to be 240 per cent in April. Those values are calculated against extremely low bases of $18 per barrel in April 2020. Therefore, these values must be interpreted carefully. The rising oil prices create a certain level of inflationary pressures, but it is much milder than what those year-on-year growth figures suggest.

Grains market

Grains prices remained firm during 2020 without experiencing a steep plunge unlike oil prices (figure 2). For the last several months, the prices are on the rise. As opposed to the market situation in 2008, the supply of grains is estimated to be sufficient to cover the demand in 2021. The world wheat production for the 2020/21 season is estimated to be a record 776.5 million tons. Among major exporters, the wheat production is forecast to be reduced for 2020/21 season in the European Union, Russian Federation and the United States due to droughts, particularly severe in the southwest of the United States. However, the increased production from other major exporters, particularly a record high harvest in Australia, is projected to be enough to make up for the decreased yields in other parts of the world. The world rice production is projected to be 502.2 million tons in the 2020/21 season, increasing 6.5 million tons from the 2019/20 season. In all major exporters, including India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand, and Viet Nam, the harvest is expected to increase. In March, the annual increase of the price of rice stood at 6.5 per cent, and that of wheat stood at 34.5 per cent. A severe price spike, as in 2008, is unlikely due to sufficient supply. However, the regional dispersion in wheat harvest may cause more prices to rise in certain locations. The situation is worrying because of international wheat prices’ substantial influence on developing countries’ headline inflation.

Base metal market

The early and robust recovery of the manufacturing sector worldwide has created a steep demand growth for base metals (figure 2). Prices of base metals have risen sharply, with the price of copper at $8988 per metric ton in March, increasing by 73 per cent from the same month last year and 49 per cent higher than the 2019 average. The price of iron ore stood at $166 per metric ton in March, increasing by 88 per cent from the same month last year and 78 per cent higher than the 2019 average. The impact of the rising base metal prices on consumer prices is not expected to be immediate, but it may create inflationary pressures in the future through rising prices of manufacturing goods.

Semiconductor chip shortage

The world economy is facing a persistent global shortage of semiconductor chips. The shortage appeared as early as July 2020 and immediately impacted the automotive industry. The shortage was initially thought to be transitory due to temporary disruptions to the supply chains. By November, however, the shortage was recognized to last much longer, and automakers revised their production plans downward. It is projected that the tight supply-demand situation will continue throughout 2021. A knock-on effect has already appeared automotive production has declined against the recovering demand. In the United States, the shortage of new cars caused a sharp rise in the price of used cars and car rental services. The semiconductor chip shortage may create a certain level of supply-push inflationary pressures until the semiconductors industry ramps up the supply capacity.

Shipping costs

The demand for international shipping has been growing due to the robust recovery of the manufacturing sector around the world. Currently, air cargos are less susceptible to potential disruptions. In February, despite the recent demand growth, cargo load factors still stood at 57.5 per cent for the industry. The restrictions on cargo flights have been lifted in the early stage of the pandemic, while many countries were still imposing various restrictions on passenger flights. Sea cargos are more susceptible to potential disruptions as recently exemplified by the blockage of the Suez Canal by a grounded container ship. Moreover, continuing border closures and travel restrictions impacted the crew changes and the repatriation of seafarers. The International Maritime Organization warned that the crew change crisis was still a challenge. As major shipping carriers reported operating at full capacity, tightening supply-demand conditions have raised freight costs. The Baltic Dry Index rose by 237 per cent in March to 2145 from a year earlier. The sea freight costs are forecast to stay high although it is still lower than the historical peak of 11482 that was registered in July 2008. As recently proposed, prioritizing COVID-19 vaccinations for seafarers and aircrew is crucial to reduce the risks of global supply chains disruptions and relieve inflationary pressures from international shipping costs.

Wages

Except for a few countries, the unemployment rates are projected to stay significantly above the pre-crisis level in 2021. The employment situation remains fragile, particularly in developing countries. In developed countries, the planned phase-out of wage subsidies and enhanced unemployment benefits may slow down job creations. Moreover, the examples of Brazil, Canada, France, Italy, and the United States indicates that the job losses during the COVID-19 crisis mainly affected those at the lower end of the wage scale who often hold little negotiation powers over wages to restore their employment status. The economic recovery invites only sporadic upward pressures on wages in a limited range of economic sectors in developed countries, but inflationary pressures through wages are expected to be very weak.

Monetary factors

Some policy discussions concern inflationary impacts of the extraordinary size of fiscal and monetary stimulus measures. In developed countries, the increased public debt for fiscal stimulus was absorbed mainly by central banks. Citing the rapid broad money growth, which reached 27 per cent in the United States in February, the critics argued that central banks were “printing money” to finance fiscal deficits. The practice, known as the monetization of fiscal deficits or money financing, is widely believed to have caused hyperinflation in Germany after the first world war, and more recently, in Sudan, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Zimbabwe. Despite this commonly held concern, inflationary pressures from this channel are yet to be found in developed countries.

There are two reasons to explain this outcome. First, the extraordinary money growth is not the result of monetary expansion through credit creation. The loans growth in developed countries remains much lower than money growth in 2020. The money growth is a result of increased savings of households that were deposited in commercial banks. Thus, the money growth did not stimulate domestic demand, and hence did not trigger inflationary pressures. Second, hyperinflation typically take place in parallel with a steep depreciation of the national currency, as seen in Sudan, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Zimbabwe, amid slumps in exports and capital inflows, and depletion of central banks’ foreign reserves. Thus, if the money growth does not trigger a significant currency depreciation, it is unlikely to create steep inflationary pressures.

For developed countries, inflation pressures from the monetary channel are expected to be limited. However, many developing countries may be subject to inflationary pressures from currency depreciation and exchange rate pass-through. The US dollar is generally strengthening against other currencies in the first quarter of 2021. The price of US Treasury bonds fell since the start of the year, reflecting weakening demand from domestic investors. However, the current yield most recently stood at around 1.6 per cent per annum for 10-year maturity bonds, providing a reasonable buying opportunity for foreign investors to lock in their funds in one of the safest assets with a decent yield. The situation may entail increasing portfolio investment inflows into the United States, redirecting portfolio investment flows from other countries, including developing countries. If the global capital flows result in further strengthening of the US dollar against other currencies, depreciation pressures will be widely felt, particularly in developing countries.

The case of Brazil

In March, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) raised its policy rate from 2 per cent to 2.75 per cent, ending the easing cycle, which lasted six years. The Monetary Policy Committee projected the inflation rate would average 5 per cent, above its 3.5 per cent target. While recognizing that the worsening COVID-19 pandemic may delay economic recovery and create a lower-than-expected future inflation trajectory, the Committee also saw a possible extension of fiscal policy response to the pandemic and other uncertainties are likely to exacerbate inflationary pressures. The Committee reasoned that the decision was a partial normalization from the extraordinary degree of monetary stimulus since some monetary stimulus measures would continue. However, the Committee stated that the BCB would continue partial normalization, and another rate hike is expected in May.

In March, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) raised its policy rate from 2 per cent to 2.75 per cent, ending the easing cycle, which lasted six years. The Monetary Policy Committee projected the inflation rate would average 5 per cent, above its 3.5 per cent target. While recognizing that the worsening COVID-19 pandemic may delay economic recovery and create a lower-than-expected future inflation trajectory, the Committee also saw a possible extension of fiscal policy response to the pandemic and other uncertainties are likely to exacerbate inflationary pressures. The Committee reasoned that the decision was a partial normalization from the extraordinary degree of monetary stimulus since some monetary stimulus measures would continue. However, the Committee stated that the BCB would continue partial normalization, and another rate hike is expected in May.

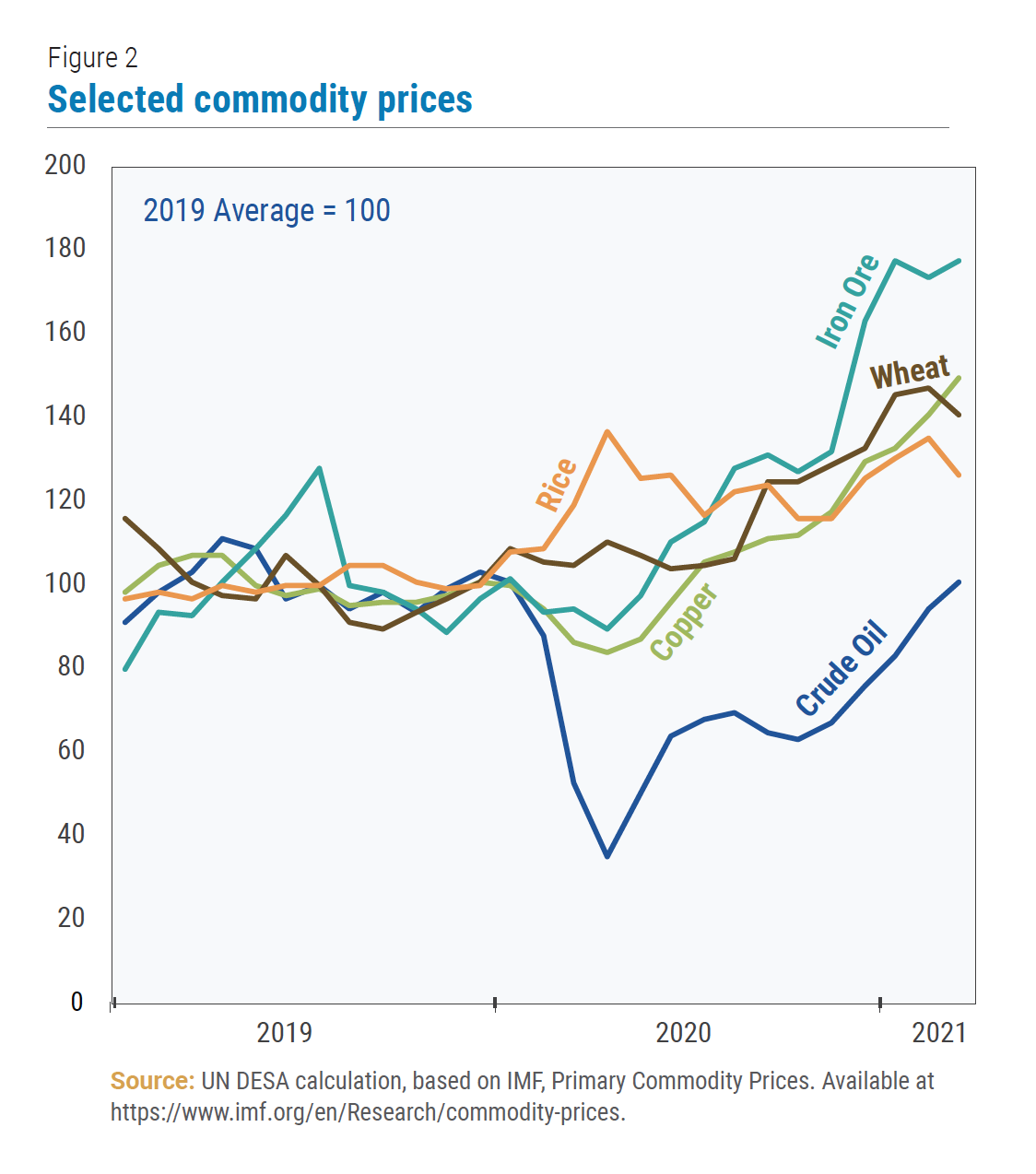

Brazil’s headline inflation stood at 6.1 per cent in March, the highest since January 2017 (figure 3). Among the main expenditure groups, the highest price hike was recorded in food and beverage with 13.9 per cent, followed by domestic goods with 9.7 per cent, and transport with 8.6 per cent. However, the core inflation, excluding food and energy prices, stood relatively stable at 2.5 per cent. The headline inflation rate had persistently been diverging from the core inflation since June last year.

The current price dynamics imply that rising food and energy prices are the main contributing factors to inflationary pressures in Brazil. In many cases in developed countries, food and energy prices are excluded from the consideration for a monetary policy decision. Food and energy prices are often externally given and not controllable by managing demand through monetary policy. However, it should be noted that headline inflation has been persistently rising over the core inflation over the last nine months, indicating a rising contagion risk of inflation from food and energy items into other expenditure items. The BCB’s tightening decision aims partly to prevent such contagion.

The tightening decision by the BCB is also supposed to aim at stabilizing the value of the national currency, the Brazilian real. Since January 2020, the Brazilian real has depreciated against the US dollar by 39 per cent. Although Brazil is one of the major producers of agricultural goods, a large part of inflationary pressures in Brazil can be explained as a combination of rising international agricultural prices and the depreciation of the Brazilian real.

The situation poses a policy challenge for Brazil. The monetary tightening is likely to prevent a contagion of inflation from food and energy into the core items. The monetary tightening also can improve external balance and reduce a risk of further inflation from exchange rate pass-through. However, it may risk the recovery, especially if monetary tightening is not timed right.

Conclusion

In 2021, an increasing number of developing countries may face a similar policy dilemma to what Brazil is currently experiencing. International prices of agricultural commodities are on the rise. The expected magnitude of the hikes is milder than the last global inflation episode during 2007–2008. The overall harvest forecast indicates that there should be sufficient supply to meet the demand globally. However, the locational dispersions in crop yield and tight sea cargo supply capacity may raise food prices in specific locations more than others.

Moreover, the magnitude of food price inflation will likely be amplified in several developing countries by currency depreciation. The combined risk of rising agricultural commodity prices and currency depreciation entails higher food inflation which exacerbates poverty levels even further. While it is crucial for a central bank to continue some monetary stimulus measures selectively to promote certain investment activities when entering the tightening cycle, the nature of food inflation requires policymakers to safeguard the poor by additional measures. Also, the international community must be ready for providing financial assistance and direct food aid to developing countries that suffer from high

food inflation.

Follow Us