World Economic Situation And Prospects: May 2019 Briefing, No. 126

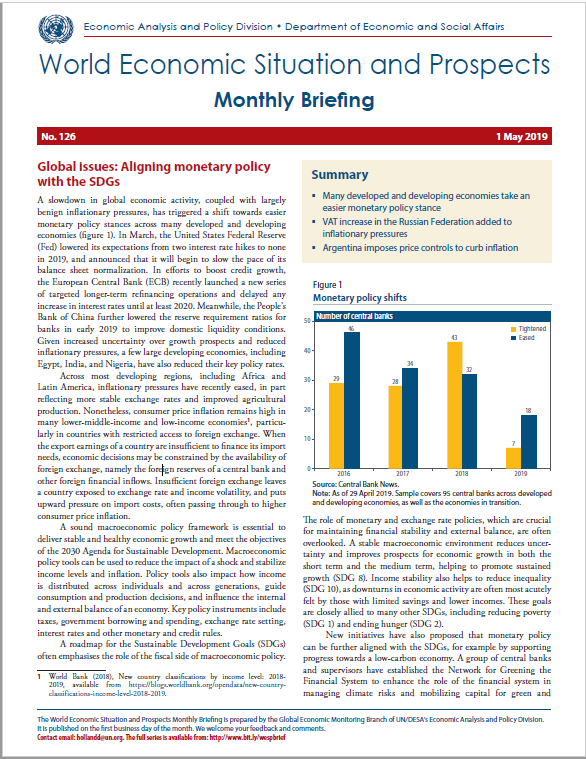

- Many developed and developing economies take an easier monetary policy stance

- VAT increase in the Russian Federation temporarily adds to inflation

- Argentina imposes price controls to curb inflation

English: PDF (168 kb)

Global issues

Aligning monetary policy with the SDGs

A slowdown in global economic activity, coupled with largely benign inflationary pressures, has triggered a shift towards easier monetary policy stances across many developed and developing economies (figure 1). In March, the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered its expectations from two interest rate hikes to none in 2019, and announced that it will begin to slow the pace of its balance sheet normalization. In efforts to boost credit growth, the European Central Bank (ECB) recently launched a new series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations and delayed any increase in interest rates until at least 2020. Meanwhile, the People’s Bank of China further lowered the reserve requirement ratios for banks in early 2019 to improve domestic liquidity conditions. Given increased uncertainty over growth prospects and reduced inflationary pressures, a few large developing economies, including Egypt, India, and Nigeria, have also reduced their key policy rates.

Across most developing regions, including Africa and Latin America, inflationary pressures have recently eased, in part reflecting more stable exchange rates and improved agricultural production. Nonetheless, consumer price inflation remains high in many lower-middle-income and low-income economies, particularly in countries with restricted access to foreign exchange. When the export earnings of a country are insufficient to finance its import needs, economic decisions may be constrained by the availability of foreign exchange, namely the foreign reserves of a central bank and other foreign financial inflows. Insufficient foreign exchange leaves a country exposed to exchange rate and income volatility, and puts upward pressure on import costs, often passing through to higher consumer price inflation.

A sound macroeconomic policy framework is essential to deliver stable and healthy economic growth and meet the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Macroeconomic policy tools can be used to reduce the impact of a shock and stabilize income levels and inflation. Policy tools also impact how income is distributed across individuals and across generations, guide consumption and production decisions, and influence the internal and external balance of an economy. Key policy instruments include taxes, government borrowing and spending, exchange rate setting, interest rates and other monetary and credit rules.

A sound macroeconomic policy framework is essential to deliver stable and healthy economic growth and meet the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Macroeconomic policy tools can be used to reduce the impact of a shock and stabilize income levels and inflation. Policy tools also impact how income is distributed across individuals and across generations, guide consumption and production decisions, and influence the internal and external balance of an economy. Key policy instruments include taxes, government borrowing and spending, exchange rate setting, interest rates and other monetary and credit rules.

A roadmap for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) often emphasises the role of the fiscal side of macroeconomic policy. The role of monetary and exchange rate policies, which are crucial for maintaining financial stability and external balance, are often overlooked. A stable macroeconomic environment reduces uncertainty and improves prospects for economic growth in both the short term and the medium term, helping to promote sustained growth (SDG 8). Income stability also helps to reduce inequality (SDG 10), as downturns in economic activity are often most acutely felt by those with limited savings and lower incomes. These goals are closely allied to many other SDGs, including reducing poverty (SDG 1) and ending hunger (SDG 2).

New initiatives have also proposed that monetary policy can be further aligned with the SDGs, for example by supporting progress towards a low-carbon economy. A group of central banks and supervisors have established the Network for Greening the Financial System to enhance the role of the financial system in managing climate risks and mobilizing capital for green and low-carbon investments. Proposals have also been put forward to introduce a low-carbon bias in the asset composition of official reserves and collateral.

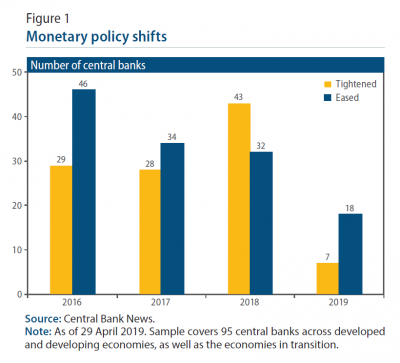

Traditional monetary policy actions, such as a rise in interest rates, are transmitted to the real economy through credit, exchange rate and asset price channels. In countries with well-developed financial sectors, impacts on credit growth and balance sheets may affect corporate sector investment decisions, housing investment and consumer spending on durable goods. In countries with less developed financial markets, the transmission of monetary policy to aggregate demand is generally less effective. Corporate investment in the formal sector may respond, but the informal sector and household sector are less sensitive to interest rates, partly because consumption expenditure is dominated by essential non-durable goods. The expenditure share of food items in the consumption basket underpinning the consumer price index (CPI) is much higher in low-income countries than in developed countries (figure 2). As such, price stability depends heavily on food price inflation.

In many low-income developing countries, this sensitivity to food price inflation is complicated by a high dependency on food imports. For example, in Sudan, food, including wheat and other staples, accounted for 24 per cent of imports in 2018, despite the fact that agriculture accounts for about 30 per cent of GDP. Furthermore, food items carry a weight of 52 per cent in the CPI basket. Sudan has been under severe foreign exchange constraints since 2011, owing to declining crude oil exports, rising import demand and dwindling foreign capital inflows. In 2018, the Sudanese pound depreciated from 6.7 pounds per US dollar to 47.5 pounds per US dollar. The sharp rise in import prices pushed consumer price inflation up to 72 per cent in December 2018. The resulting plunge in real incomes triggered widespread social protests.

In many low-income developing countries, this sensitivity to food price inflation is complicated by a high dependency on food imports. For example, in Sudan, food, including wheat and other staples, accounted for 24 per cent of imports in 2018, despite the fact that agriculture accounts for about 30 per cent of GDP. Furthermore, food items carry a weight of 52 per cent in the CPI basket. Sudan has been under severe foreign exchange constraints since 2011, owing to declining crude oil exports, rising import demand and dwindling foreign capital inflows. In 2018, the Sudanese pound depreciated from 6.7 pounds per US dollar to 47.5 pounds per US dollar. The sharp rise in import prices pushed consumer price inflation up to 72 per cent in December 2018. The resulting plunge in real incomes triggered widespread social protests.

The example of Sudan illustrates a policy challenge common to economies that are faced with both a shortage of foreign exchange and high dependency on food imports. As they aim to stabilize food prices, interest rates may be used in conjunction with exchange rate policy, although this usually relies on having some form of capital controls in place. Under a managed exchange rate regime, the exchange rate can be used as a tool to offset global food price fluctuations. This can help to preserve domestic price stability and also further progress towards development goals by safeguarding low-income households, which are particularly sensitive to food price inflation. However, for this to be sustainable, when global food prices rise, the monetary stance may need to be tightened to curb import demand for non-essentials, which may also hamper investments that the country desperately needs for economic growth and development. In addition, holding the exchange rate at an artificially high level leads to a loss of export competitiveness, may encourage a dual exchange rate or black market activities, depletes foreign reserves, and may eventually culminate in a steep and sudden devaluation. Ultimately, the root causes of foreign exchange shortage must be tackled through export sector development and agricultural development to reduce dependency on imported food.

Developed economies

North America: Federal Reserve softens monetary stance

Following the Federal Open Market Committee’s meeting in March, the Fed stressed that the Committee “will be patient as it determines what future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate may be appropriate”, and voting members delayed their expectations for the next interest rate rise until 2020. While wage growth has been steadily rising—reflecting some tightness in the labour market with the unemployment rate standing at one of the lowest levels recorded in the last 40–50 years—headline consumer price inflation hovers just below the 2 per cent target. The change in the Fed’s message on monetary policy reflected a more pessimistic expectation on the economy following the increased financial volatility as observed by the end of 2018, the persistent trade tensions, and the waning effects of fiscal stimuli. Inflation in the United States remains sensitive to oil price movements. Should oil prices continue to rise over the coming months, this could push headline inflation above 2 per cent, and potentially lead to a reassessment of the appropriate level of the federal funds rate.

Japan: Consumer price inflation remains below target

With consumer price inflation projected to be well below the 2 per cent target over the next two years, the Bank of Japan has indicated its intention to continue with its quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) programme. When the QQE programme was introduced in 2012, the central bank expected to achieve its inflation target by 2019. The inflation rate in March stood at just 0.5 per cent. Despite ongoing labour shortages, which have contributed to the increasing number of business closures, wage growth remains insufficient to generate inflationary pressures. In February, real wages declined by 1.1 per cent compared to last year.

Europe: Subdued inflation on an upward trend

Inflation remains subdued in Europe, amid increasing upward wage pressure. The euro area saw inflation rise from 0.2 per cent in 2016 to 1.5 per cent in 2017 and 1.7 per cent last year. Inflation is expected to remain steady this year, as an easing in the upward pressure from energy prices is offset by increasing pressures on the domestic side. Employment has been increasing throughout the region, with unemployment falling to the point where in some subregions there is a shortage of labour. This is propelling stronger wage growth, which in turn is supporting domestic demand. As monetary policy is expected to remain more accommodative for a longer period than previously expected, this will continue to support investment and the construction sector in various countries. However, overall economic activity has slowed across the region as a result of the disruption in auto production, weaker confidence, and softer external demand. Inflation is forecast to remain within the ECB’s policy target of below, but close to, 2 per cent.

Persistent labour shortages in countries that joined the European Union since 2004 spurred strong growth in nominal wages in 2018; in early 2019 this trend continued, threatening several economies with a wage-price spiral. In the Czech Republic, headline inflation reached 2.7 per cent in February, and contrary to global easing trend some central banks in the region may tighten monetary policy further this year.

Economies in transition

CIS: VAT increase in the Russian Federation has inflationary impact

In the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Russian Federation experienced a lengthy period of disinflation from late 2015 to mid-2018, due mainly to ample harvests and a rebound of the rouble. In early 2018, inflation slowed to an all-time record low of 2.2 per cent, far below the central bank’s target of 4 per cent. However, inflation accelerated later in the year because of the sluggish harvest and depreciating currency, reaching 4.3 per cent in December. The increase in the VAT rate in January 2019 further pushed inflation up, to 5.2 per cent in February. The contribution of the VAT rise was nevertheless moderate and was mitigated by the strengthening of the rouble in the first quarter, explained by the strong demand for the Russian sovereign bonds and rouble purchases for tax payments by the export-oriented companies. Since the central bank has already pre-emptively increased its policy rate in late 2018, no further tightening of monetary policy is expected in 2019. The accelerated inflation has nonetheless undermined consumer spending, as real incomes continue to contract for the fifth year in a row; and was one of the factors behind the sharp growth slowdown in the first quarter. In Ukraine, inflation in December stood at 9.8 per cent, but gradually tapered to 8.4 per cent in March this year thanks to the stronger currency. However, the increases in minimum wage and pensions, the planned rise in household natural gas tariffs, and possible delays in receiving IMF tranches may pose inflationary risks.

Developing economies

Africa: Inflation remains a crucial macroeconomic challenge in some economies

The recent monetary policy shifts in developed economies, coupled with relatively subdued inflationary pressures, have opened monetary policy space to support growth in several African countries. Since the beginning of the year, six countries (Angola, Egypt, Gambia, Ghana, Malawi and Nigeria) have cut interest rates to support economic activity. These decisions have been underpinned by lower inflationary risks, greater exchange rate stability and higher levels of reserves. However, inflation rates in many of these countries remain elevated.

In other countries in the region, inflation remains persistently high. In Zimbabwe, the annual inflation rate peaked at 66.8 per cent in March—the highest inflation rate since hyperinflation in 2008, as economic, financial and liquidity conditions deteriorate further. Despite the introduction of a new transitional currency in February, prices of staples including sugar, cooking oil and rice have risen as much as 60 per cent, squeezing already hard-pressed consumers. Even higher inflationary pressures are likely to materialize in the near term due to a devastating El Niño-induced drought and torrential rains brought by Cyclone Idai. Zimbabwe plans to establish a monetary policy committee and set a benchmark interest rate as part of its plans to stabilize the economy.

In South Sudan and Sudan, inflation hovered at 40–45 per cent during the first quarter of 2019, mainly as a result of the monetization of fiscal deficits to finance conflict-related spending. The concurrent loss of purchasing power has meant that many employees and business owners have been driven into poverty. Increased oil output and reduction in violence have contributed to disinflation in South Sudan, but extreme levels of acute food insecurity persist as well as risk of famine. In Sudan, significant protests erupted in December over the rising costs of bread and fuel. The social uprising intensified in recent months, culminating in the removal of President Omar al-Bashir from power.

East Asia: Monetary policies likely to remain accommodative amid high external uncertainty

Amid subdued inflation and high uncertainty in the external environment, monetary policy in most of the East Asian economies is likely to remain accommodative in the outlook period. The recent pausing of the monetary policy normalization process in the developed economies has also reduced capital outflow pressures for the region.

In early 2019, China further lowered the reserve requirement ratios for banks in an effort to improve domestic liquidity conditions. Following a series of rate hikes in 2018, Indonesia and the Philippines have kept interest rates unchanged this year, given increased downside risks to growth. In the Republic of Korea, the central bank removed a reference to possible monetary policy tightening in the near term, while simultaneously downgrading its growth and inflation projections.

For many East Asian countries, policymakers are facing an increasingly challenging task of supporting short-term growth while reining in financial imbalances. In China, the easing of credit conditions may fuel a further rise in corporate debt, increasing the risk of a sharp deleveraging process in the future. In Thailand and the Republic of Korea, high household debt is increasingly being seen as a source of risk to financial stability. In this environment, central banks in the region are likely to adopt a cautious approach to any further monetary easing, while utilizing macroprudential tools to target financial vulnerabilities in specific sectors of the economy.

South Asia: Inflation is moderate in India, but surging in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Inflation rates across South Asia are forecast to remain largely similar to 2018. India is expected to record a 4.7 per cent price increase, slightly below the 5-year average of 4.9 per cent. This opened some space for monetary policy loosening, and interest rates were cut by 25 basis points in both February and April. Nevertheless, as banks remain constrained by non-performing loans and a large share of credit is provided by non-bank institutions, the monetary policy transmission remains weak in India. The impact of the rate cuts on the economy and inflation will therefore be limited. Prices are forecast to grow faster in Pakistan, at an annual rate of 7.3 per cent in 2019. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, inflation is expected to exceed 20 per cent. In the rest of the region, prices are forecast to grow by around 4 per cent in 2019.

During the 2018–2019 period, food price inflation has been at an almost three-decade low in India. In March, food prices increased by only 0.3 per cent on a year-on-year basis. Food price stabilisation is particularly important for the more than 10 per cent of the population who live in extreme poverty, given that the household budgets of the poorest consist almost entirely of food expenditure. In Pakistan, on the other hand, food price inflation stood at 8.2 per cent in March 2019. Combined with a slowing economy, this could substantially hinder poverty reduction efforts. The situation is slightly better in Bangladesh, with food prices increasing by 5.7 per cent. Meanwhile, food price inflation in the Iranian economy has reached over 70 per cent, reflecting the impact of economic sanctions. Combined with high unemployment and a dire economic outlook for 2019, the poor are most severely impacted.

Western Asia: Decelerating consumer price inflation

In Western Asia, consumer price inflation is decelerating in most countries, with the exception of Syria where the economy faces considerable inflationary pressures linked to economic sanctions. As a regional trend, the price of food items is moderately declining due to stable international grain prices. Furthermore, the weakening real estate sector pushed down prices of housing-related items in several energy-exporting countries of the region. Annual consumer price inflation in February stood at 0.9 per cent in Bahrain, 0.6 per cent in Kuwait, 0.2 per cent in Oman, -1.4 per cent in Qatar, -2.2 per cent in Saudi Arabia and -2.5 per cent in the United Arab Emirates. The deflation in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates reflects weak domestic demand expansion in those countries in 2019. The inflation rate in Lebanon and Jordan has also come down from the recent peak in July 2018. In February, the inflation rate stood at 0.2 per cent in Jordan and 3.1 per cent in Lebanon. Although still high, the inflation rate in Turkey decelerated to 19.7 per cent in March from the recent peak of 25.2 per cent in November 2018. The inflation rate is forecast to decelerate further due to the waning impact of exchange rate pass-through from the substantial depreciation of the Turkish lira last year.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Argentina’s Government imposes price controls to contain inflation

Following a volatile financial environment during 2018, the recent monetary shifts by the Fed and other major global central banks have been welcome news for the economies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Portfolio capital flows to the region rebounded in early 2019, pushing up the prices of local assets. Regional currencies, including the Brazilian real, the Chilean peso and the Colombian peso, stabilized after losing ground to the dollar in 2018. This has helped offset rising oil prices, keeping inflationary pressures largely in check. In most countries, inflation rates were within the target range of monetary authorities during the first quarter of 2019. Central banks thus have some room to maneuver should the economic outlook deteriorate.

The inflation situation is very different in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and Argentina. The former faces sky-rocketing hyperinflation amid shortages of food and basic goods, the monetization of large fiscal deficits, and a rapid depreciation of the currency in the parallel market. In Argentina, year-on-year inflation rose to 51.4 per cent in the first three months of 2019 as monetary tightening measures failed to halt upward price pressures. In response, the central bank reinforced the contractionary bias of monetary policy. At the same time, the Government unveiled a new program of price controls, temporarily freezing the prices of 60 essential products and public services, including gas, electricity and public transportation.

Follow Us