World Economic Situation And Prospects: March 2018 Briefing, No. 112

- Stock market volatility returns amid concerns over inflation and monetary policy tightening

- Macroprudential policy measures in emerging economies can help address financial vulnerabilities and limit systemic risks

- Global investment conditions have improved markedly, but investment gaps remain large in many developing countries

English: PDF (283 kb), EPUB (308kb)

Global issues

Emerging economies must weigh support for investment against a further build-up of financial risks

After a long period of subdued growth, the global economy has strengthened, supported by the revival of investment and trade, robust business and consumer sentiment and improving labour market indicators. Since early 2017 global investment conditions have improved, underpinned by reduced banking sector fragilities in developed countries. Financing costs and spreads in emerging economies remain relatively low, supported by the recovery of capital flows and cross-border lending and higher commodity prices. However, the prolonged period of abundant global liquidity and low borrowing costs has also allowed financial vulnerabilities to build, fuelling investors’ search for yield and encouraging an under-pricing of risk.

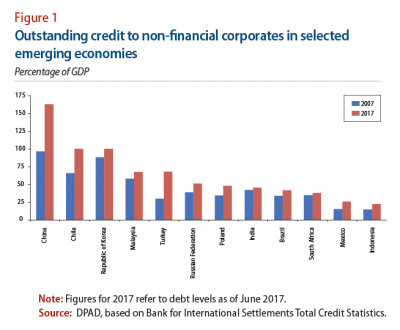

This period of extremely loose global financial conditions has pushed up asset prices and spurred rapid credit growth in many emerging economies. On average, debt levels of non-financial emerging market corporates exceeded 100 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, up from 60 per cent in 2007 (figure 1). Household debt levels and residential property prices have also escalated, most notably in parts of Asia.

As the normalization of monetary policy in the United States and other developed economies gains momentum, financial markets may be subject to large corrections and sudden spikes in volatility. This has been illustrated by the widespread equity market sell-off in early February. In emerging economies, the prospects for tighter global liquidity conditions could reduce capital flows, leading to higher borrowing costs, currency depreciation and a decline in equity prices. This could adversely impact banking and corporate sector balance sheets as well as the capacity to roll over debt. These shocks could also severely constrain real economic activity, through a sharp slowdown in investment, higher inflation or fiscal adjustment measures.

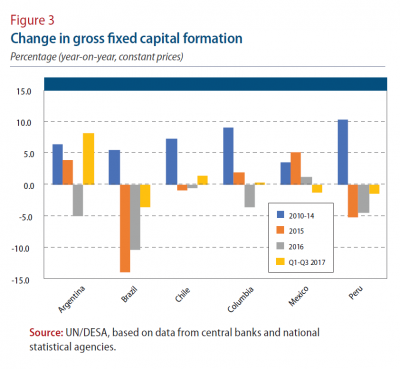

Macroprudential policies can help contain the build-up of risks and increase the resilience of the financial system to shocks. These measures allow policymakers to target sector-specific vulnerabilities and to address systemic risks. When coordinated with monetary and fiscal policies, macroprudential measures can also help to align financial and business cycle conditions in the domestic markets, ensuring support to real economic activity and consistency between the objectives of price and financial stability (see figure 2).

Several countries, especially in East Asia, have recently tightened macroprudential measures. In 2017, the rapid rise in real estate prices prompted the Republic of Korea to lower the loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios for property purchases in select regions. For homeowners with more than three homes, a capital gains tax of 20 percentage points on top of the existing levy was also imposed. These measures also aimed to rein in household debt, which, at 90 per cent of GDP, is one of the highest in Asia.

In China, policymakers are giving more priority to macroprudential measures to reduce corporate debt, particularly debt of State-owned firms. In efforts to lower default risks, the debt-to-equity swap programme was accelerated, while new restrictions were recently imposed on banks’ acquisition of entrusted loans, which constitute riskier assets. To reduce speculation in the property sector, several major cities imposed tighter purchase restrictions, including higher mortgage down payments and a ban on the resale of new homes within a specified time period. As property prices continued to soar, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China further tightened regulations on mortgage loans in 2017. These measures included lowering the loan-to-value ratio for borrowers with more than one pre-existing mortgage and lowering the debt service ratio for borrowers whose incomes are mainly derived from outside of Hong Kong SAR.

Macroprudential measures are increasingly becoming an integral part of the policy toolkit of many emerging economies. Thus, there is also a growing body of empirical literature that assesses their effectiveness, offering important insights to policymakers. These studies confirm that macroprudential instruments can play a role in mitigating financial vulnerabilities and containing the procyclical pressures in credit markets, thus contributing to greater financial stability. In particular, the use of loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios has dampened credit expansion, for example in Asian and Latin American economies. However, macroprudential instruments display varying degrees of success in addressing financial risks. For instance, targeted measures seem to be more effective than broad-based measures in restraining credit growth in a specific sector, such as the housing market. Several studies also emphasize that macroprudential measures tend to be more effective in the boom rather than the bust phase of the financial cycle and when complemented with other policies. For example, several studies on Latin America suggest that the effectiveness of reserve requirements and dynamic provisioning depends on the contemporaneous use of traditional monetary policy instruments.

As the pace of monetary policy normalization in developed economies accelerates, emerging economies should prepare for a period of potentially lower and more volatile capital flows and tighter global liquidity conditions. Depending on the financial and business cycle conditions in domestic markets, a more active use of macroprudential policy measures is warranted in many economies. This could soften the impact of tighter global liquidity and greater financial volatility, and allow greater scope for supportive policy measures in the future.

Developed economies

More rapid withdrawal of monetary stimulus likely, but investment conditions remain supportive

In developed economies, stronger GDP growth has coincided with an easing of the deflationary pressures that posed a key policy concern in 2015–2016. The disruption of global stock markets in early February was triggered by news of stronger wage growth in the United States than had been expected. Average hourly earnings in the private sector rose by 2.9 per cent in the year to January, the highest wage growth since 2009. Some inflationary pressures have also started to build in Europe. In Germany, employer and union representatives in the machinery sector have struck a new wage agreement that is estimated to increase labour costs by up to 3.5 per cent in 2018 and 2019. This is indicative of the record-low unemployment and a shortage of workers. Labour shortages have also become a concern in Japan, which has spurred investment in research and development and labour-saving technology. Longer-term inflationary expectations have also edged up in North America, Europe, and even in Japan, where deeply entrenched deflationary expectations have built up over two decades.

While inflation remains close to or below target in most developed economies, the normalization of inflation rates has prompted expectation of a more rapid withdrawal of monetary stimulus. Financial markets have priced in at least two additional quarter-point interest rate rises by the United States Federal Reserve by end-2019 compared to what had been anticipated in November 2017. The Bank of England has hinted that it may tighten its policy stance earlier than previously expected, in light of relatively strong global growth, expectations of strengthening wage growth and an above-target inflation rate that stems from the exchange rate impact of the decision to leave the European Union (EU). The probability that the European Central Bank (ECB) will reduce its expansionary policy stance sooner than expected has also increased. At the same time, the Czech National Bank and the National Bank of Romania have recently started tightening their monetary stance amid concerns of the emergence of another housing bubble in the region and above-target inflation in both countries.

The withdrawal of monetary stimulus in developed economies does not necessarily herald a significant tightening of investment conditions in the short-term. The spreads of corporate over government bond yields—a measure of the premium that firms pay over “risk-free” interest rates—remain at very low levels; bank lending surveys point to easier or stable lending conditions for most categories of borrowers and stable demand for credit; while rising wages will underpin strong household consumption. This is expected to support steady investment growth in developed economies this year. Nonetheless, as the era of zero interest rates comes to an end, a more prudent approach to lending and borrowing is merited, to ensure that debt that carries a variable interest rate or that will be reissued at a higher rate of interest in the future does not become destabilizing.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Monetary loosening in the Russian Federation may accelerate

In the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Central Bank of the Russian Federation has been gradually reducing its key policy rate since 2015, bringing it down to 7.5 per cent in February 2017, after record low January inflation of 2.2 per cent. Disinflation was supported by the relatively strong rouble, sluggish consumer demand and the ample harvest in 2017. Monetary loosening was cautious, while inflation has decelerated rapidly, and interbank lending rates in late 2017 were below the policy rate. Longer-term borrowing rates have also declined notably. Still, real borrowing costs remain high. Although low inflationary expectations are not fully anchored yet and the 2018 World Cup may cause a price spike, monetary loosening may be accelerated to achieve a “neutral” stance. The recent global market volatility and expectations of tightening by the United States Federal Reserve and the ECB, however, may impact those decisions. Gross fixed investment, which sharply contracted in 2015 and 2016, has recovered in 2017, expanding by 3.9 per cent. The international sanctions environment and the possibility of further sanctions by the United States, however, are holding back both foreign and domestic investment. In many other CIS economies, banking sectors are marred by the high ratio of non-performing loans; State support was provided to the banking sector in Kazakhstan. Although in Ukraine the strong pick-up in investment observed since 2016 is mostly domestically financed, it follows three years of deep contraction. In Central Asia, the implementation of the “Belt and Road” initiative projects should facilitate business and infrastructure investment.

In South-Eastern Europe, monetary policy remains accommodative; investment has also picked up in 2016–2017, supported by the gradual recovery in credit growth and several large-scale infrastructure projects.

Developing economies

Africa: Challenging conditions to finance sustainable development continue

Despite the prevalence of significant risk factors, including political instability, poor governance and social unrest, African countries have maintained a relative level of investment on par with the world average. During the period 2012–2016, gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP averaged 23.3 per cent for African economies, compared to a world average of 23.4 per cent.

However, African economies face financing constraints to maintain investment levels. Domestic savings are not sufficient to finance investment in most countries. Gross domestic savings in Africa have been decreasing since 2012 and amounted in 2016 to just 11 per cent of GDP, far below the world average of 24.8 per cent. Export revenue has decreased as a share of GDP since 2012, due to weak commodity prices. Remittance flows to Africa decreased in 2015 and 2016 by 4–5 per cent, due to weak growth in Europe and the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), although some recovery was seen in 2017. The value of foreign direct investment has also decreased as a share of GDP since 2012.

As a result, the dependency on external borrowing has increased. Since 2014, the median external debt as a share of gross national income among African countries increased 7 percentage points to 36 per cent, reversing a downward trend that began in 2003. Abundant liquidity conditions in developed countries and global investors’ hunt for yield also incentivized some African countries to tap international capital markets through bond issuances. While the issuance of Eurobonds can be seen as an indication of the continent’s economic recovery, it also requires close scrutiny of public financial management and debt sustainability, especially against a backdrop of low commodity prices, potential for a stronger US dollar and rising global interest rates.

East Asia: Favourable investment outlook but risks remain

Recent indicators show a continued strengthening of investment activity in the major East Asian economies. Amid positive business sentiments, capital spending in the region has been buoyed by improving demand and accommodative policy stances. In the fourth quarter of 2017, gross fixed capital formation growth in Indonesia accelerated to 7.3 per cent, driven by a double-digit expansion in machinery and equipment expenditure. In Malaysia, private investment growth picked up to 9.2 per cent, due to stronger capital expenditure in the services and manufacturing sectors. Meanwhile, public investment continued to grow at a strong pace in China, the Republic of Korea and the Philippines, as Governments embarked on large infrastructure projects. Rising capacity utilization rates are also supporting private investment growth in the region, particularly in the export-oriented industries.

Looking ahead, the favourable global environment and robust domestic demand will continue to support investment activity in East Asia. Nevertheless, policymakers need to carefully balance supportive investment conditions against a build-up of financial risks. The recent spikes in global financial market volatility have highlighted the region’s susceptibility to sudden shifts in investor sentiments. A sharper correction in equity markets and a large reversal of capital flows could disrupt domestic financing conditions. This could also expose vulnerabilities related to elevated corporate debt in several countries, which constrains the ability of firms to undertake new investment plans.

South Asia: Financial and investment conditions are largely favourable in most economies

Financial and investment conditions continue to be broadly favourable in most South Asian economies, amid accommodative monetary policies, low and relatively stable inflation and robust business confidence. The positive growth picture, together with policy reforms in some areas, is underpinning private investments in several economies. For instance, investment demand in Pakistan has gained further momentum recently, supported by healthy economic activity, improvements in the energy system, and large infrastructure projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and other public initiatives. Official data also point towards a visible rise in loan demand during the first two quarters of the fiscal year 2017/18, especially in the corporate sector. But despite this cyclical upturn, Pakistan’s economy needs to further lift its potential growth, and lay the foundation for more sustained and inclusive growth in the medium term. In Bangladesh, investment demand remains a crucial driver of growth, supported by dynamic credit growth and regulatory and policy measures. For instance, several public initiatives are targeting foreign investments, particularly in the power, energy and medical sectors. There are also favourable prospects regarding foreign investments in the Special Economic Zones in the near term. In Nepal, fixed investment remains vigorous, driven by reconstruction efforts, including through large public and private infrastructure projects. In the near term, inflows and loans from China and India are also expected to facilitate new investments, especially in the energy and transport sectors. Going forward, the promotion of investments should remain a key policy priority across the region, particularly as a means to strengthen productivity growth in the medium term. But policymakers should also ensure that domestic and foreign debt, and non-performing loans, remain manageable, to maintain financial stability in the region.

Western Asia: A sign of polarizing investment prospects

As oil prices rose above $60 per barrel, financial and investment conditions have seen a moderate improvement in the region’s major oil-exporters. The recovery in oil revenues led to expansionary government budgets in the new fiscal year. For example, Saudi Arabia included a steep rise in capital expenditures for public investment projects in its budget. Meanwhile, despite the recent surge in the benchmark US dollar lending rate, the lending rates in GCC countries have reacted only slowly. A comparison between 3-month money market lending rates shows that the spread over US dollar rates fell to 14 basis points in January for Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In January 2016, the spread stood at 43 basis points for the United Arab Emirates, 109 basis points for Kuwait and 102 basis points for Saudi Arabia. The United States’ policy interest rate hike has yet to show a negative impact for financing conditions for investments in GCC countries.

However, financial and investment conditions remain challenging in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey where geopolitical risks dominate. The spread over the benchmark US dollar lending rate did not narrow for these countries’ lending rates, indicating tightening financial conditions and geopolitical risk-related premia.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Recovery in investment is expected to underpin growth

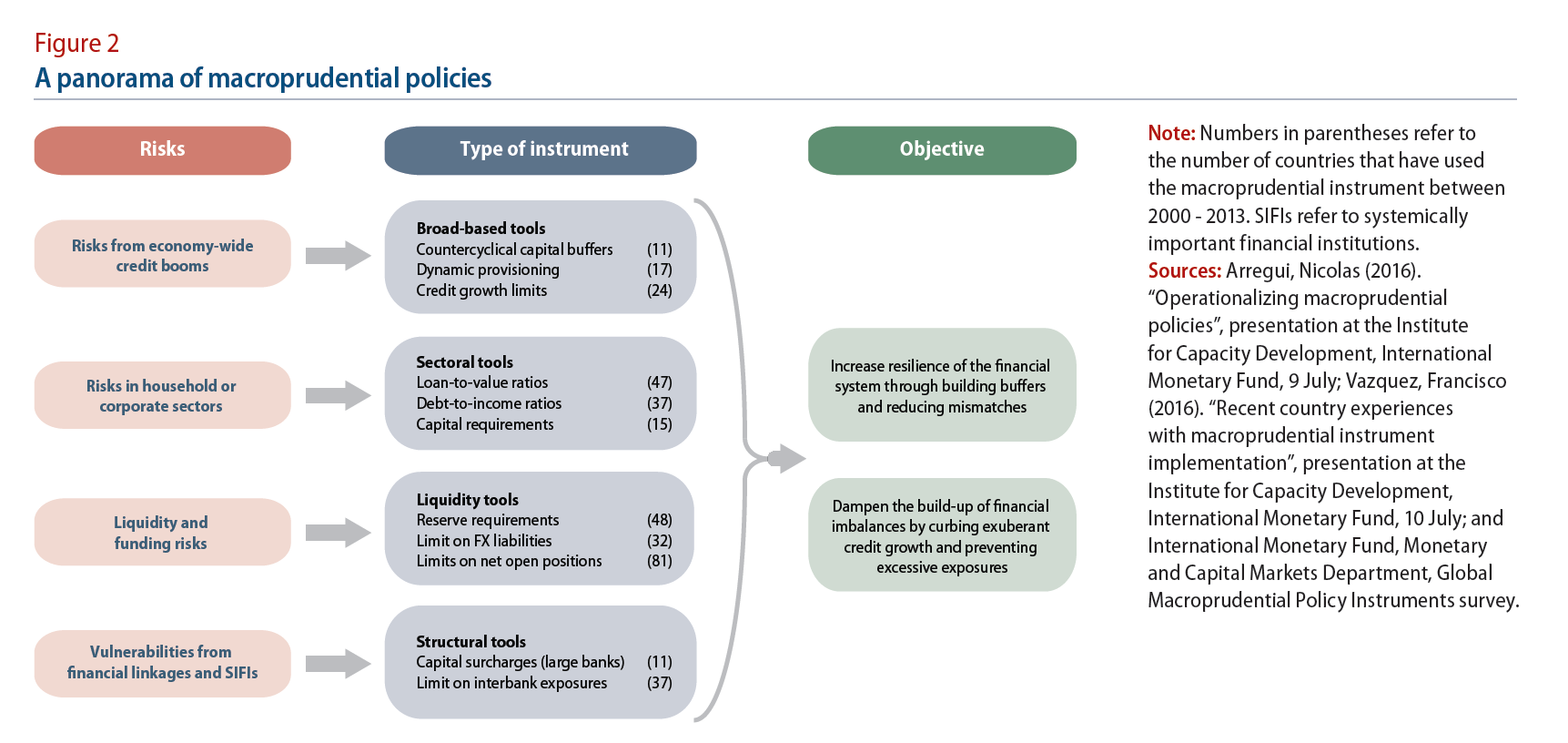

The region is in the midst of an economic recovery, supported by benign global conditions and an end of the recession in Argentina and Brazil. Private consumption and, to a lesser extent, exports, drove the region’s return to growth in 2017. Investment has lagged behind, but is no longer a drag on aggregate growth. During the first three quarters of 2017, gross fixed capital formation resumed growth in Argentina, Chile and Colombia, while the rate of decline slowed in Brazil and Peru (figure 3). Mexico, however, saw a deterioration amid uncertainty over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations and tighter monetary policy. Going forward, investment, especially in South America, is projected to strengthen further, underpinning the recovery. This mildly optimistic outlook is based on several factors. First, rising prices for metals and other commodities are expected to spur investment in extractive industries. In Chile, copper and lithium mining companies have increased their investment plans for the next decade as demand for both metals is boosted by the rise in electric cars. Second, following a broad-based monetary easing cycle, interest rates are at low levels in most countries. With inflation projected to remain mild, accommodative monetary conditions will likely remain in place for some time. Third, tax reforms and business-friendly policies could provide a temporary boost to investment in several countries, including Argentina, Brazil and Chile. Argentina’s Government recently proposed a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 25 per cent and the lowering of employer social security contributions.

The region is in the midst of an economic recovery, supported by benign global conditions and an end of the recession in Argentina and Brazil. Private consumption and, to a lesser extent, exports, drove the region’s return to growth in 2017. Investment has lagged behind, but is no longer a drag on aggregate growth. During the first three quarters of 2017, gross fixed capital formation resumed growth in Argentina, Chile and Colombia, while the rate of decline slowed in Brazil and Peru (figure 3). Mexico, however, saw a deterioration amid uncertainty over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations and tighter monetary policy. Going forward, investment, especially in South America, is projected to strengthen further, underpinning the recovery. This mildly optimistic outlook is based on several factors. First, rising prices for metals and other commodities are expected to spur investment in extractive industries. In Chile, copper and lithium mining companies have increased their investment plans for the next decade as demand for both metals is boosted by the rise in electric cars. Second, following a broad-based monetary easing cycle, interest rates are at low levels in most countries. With inflation projected to remain mild, accommodative monetary conditions will likely remain in place for some time. Third, tax reforms and business-friendly policies could provide a temporary boost to investment in several countries, including Argentina, Brazil and Chile. Argentina’s Government recently proposed a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 25 per cent and the lowering of employer social security contributions.

Follow Us