World Economic Situation and Prospects: July 2022 Briefing, No. 162

Mixed views on global economic outlook amid rising inflation and volatile markets

The global macroeconomic picture continues to evolve. On 15 June, the Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, hiked its main policy rate by 0.75 percentage points—its largest increase in 28 years. The rate hike was higher than had been expected. Since the US consumer price inflation rate is increasingly likely to remain high as its core rate reached 6.0 per cent in May, the US central bank is expected to raise the policy rates further in the coming months. Soon after, the Swiss National Bank raised its policy interest rate for the first time in 15 years amid mounting inflation expectations, despite the core inflation still standing at 1.7 per cent in May. The European Central Bank has also announced its intention to raise its policy rate in July as the euro area’s core inflation reached 3.8 per cent in May.

Since February, the successive monetary tightening measures in the United States have already profoundly impacted developing countries’ monetary policy stances. By June 2022, 37 developing country central banks began monetary tightening, in addition to a few countries—such as Brazil—that had already entered the tightening cycle last year. More countries, particularly in Africa, are expected to enter a monetary tightening phase following the expected policy rate hike of the European Central Bank. As of June 2022, only a few countries, mainly in East and Southeast Asia, including China, Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, have yet to announce their intention to tighten their monetary policy stances.

Turbulent financial markets with volatile government bond yields

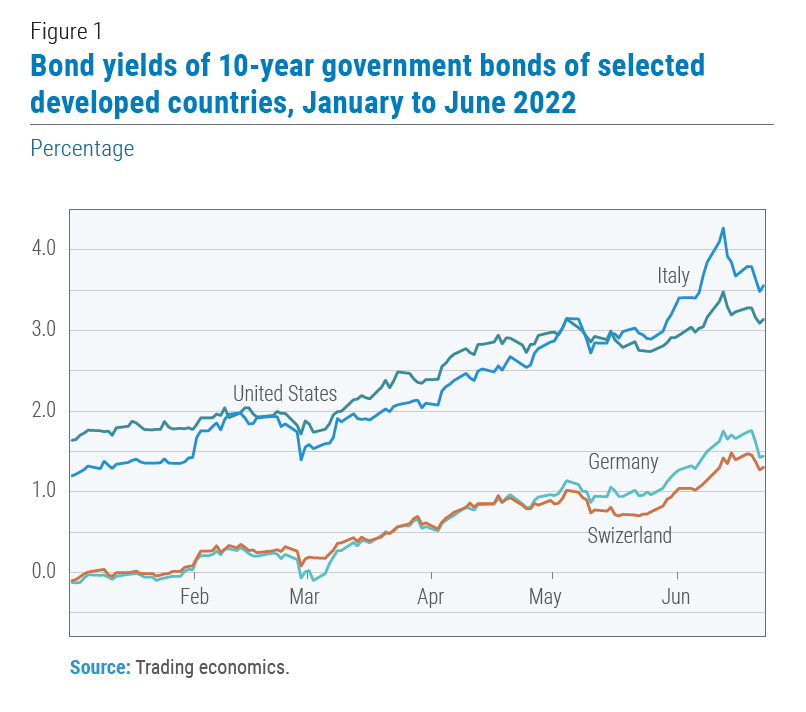

Major stock market indices continued to slide in June, following the trend since January 2022. However, recent monetary policy announcements caused turbulence in bond markets with rising yields (declining prices) of long-term government bonds with high volatilities. For example, the yield on US 10-year treasury stood at 2.91 per cent on 1 June, peaked at 3.50 per cent on 14 June, and receded to 3.0 per cent on 23 June. In Europe, the 10-year German government bond yield stood at 1.18 per cent on 1 June, peaked at 1.76 per cent on 21 June, and receded to 1.44 per cent on 23 June. (figure 1)

Major stock market indices continued to slide in June, following the trend since January 2022. However, recent monetary policy announcements caused turbulence in bond markets with rising yields (declining prices) of long-term government bonds with high volatilities. For example, the yield on US 10-year treasury stood at 2.91 per cent on 1 June, peaked at 3.50 per cent on 14 June, and receded to 3.0 per cent on 23 June. In Europe, the 10-year German government bond yield stood at 1.18 per cent on 1 June, peaked at 1.76 per cent on 21 June, and receded to 1.44 per cent on 23 June. (figure 1)

Several financial and economic factors influence the yield of long-term bonds. In principle, a long-term bond’s yield goes up in the bond market with inflation expectations. With rising inflation expectations, investors demand higher yields to compensate for the expected future loss of real value. Thus, bond markets evaluate the effectiveness of a monetary policy stance against inflation. If the policy stance is deemed effective in curbing inflation sooner, the bond yield goes down (price goes up). If the policy is considered ineffective against inflation, the bond yield goes up (price goes down).

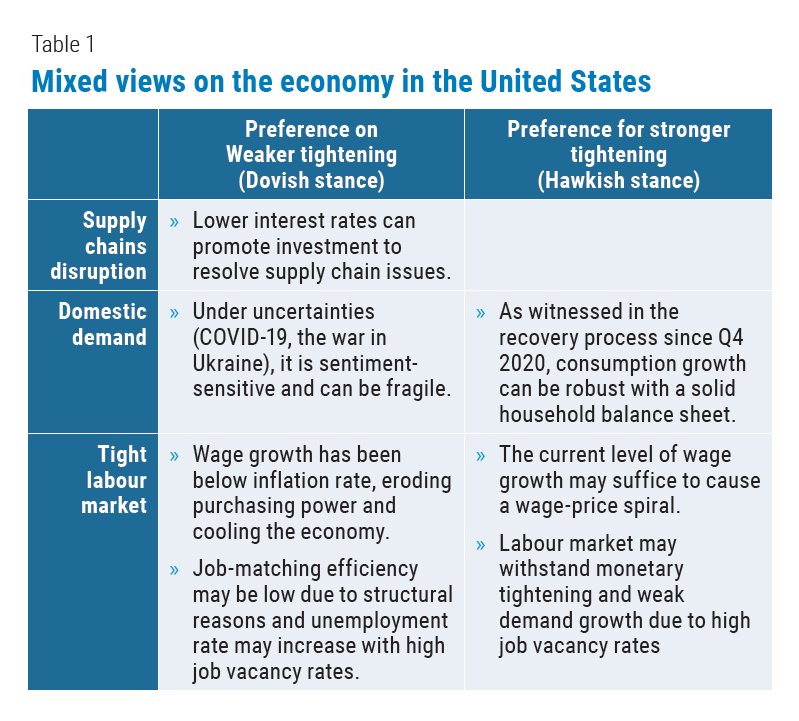

The fluctuating long-term bond yields reflect mixed views on inflation expectations in relation to monetary policy announcements. The consensus had already emerged in the United States and Europe that the nature of current inflation is not transitory, which provided the rationale for monetary tightening. Until mid-2021, the predominant view in the United States and Europe was that the rising price level was due to global supply chain disruptions; thus, the nature of inflation could be transitory and be curbed as supply chain disruptions were resolved. This view, prevailing in mid-2021, held that a tighter monetary stance could harm economic recovery (table 1).

There is, however, no consensus regarding the extent of monetary tightening that would be required to contain inflation without risking a recession. In most cases in the past, inflation expectations go up in parallel with the expectation of economic growth. Currently, however, the macroeconomic picture remains complicated. Most economies are still in a recovery phase from the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic under ongoing supply constraints from global supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine. Therefore, the current views vary, particularly in the United States, regarding the relationship between inflation and the economy’s resilience. While some consider that mild tightening may contain inflationary pressures (so-called “dovish” stance), the others insist on more substantial tightening to control inflation (so-called “hawkish” stance) (table 1). The bond yield fluctuations in June in developed countries, particularly in the United States, reflected the swings in the views between the hawkish stance and the dovish stance.

There is, however, no consensus regarding the extent of monetary tightening that would be required to contain inflation without risking a recession. In most cases in the past, inflation expectations go up in parallel with the expectation of economic growth. Currently, however, the macroeconomic picture remains complicated. Most economies are still in a recovery phase from the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic under ongoing supply constraints from global supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine. Therefore, the current views vary, particularly in the United States, regarding the relationship between inflation and the economy’s resilience. While some consider that mild tightening may contain inflationary pressures (so-called “dovish” stance), the others insist on more substantial tightening to control inflation (so-called “hawkish” stance) (table 1). The bond yield fluctuations in June in developed countries, particularly in the United States, reflected the swings in the views between the hawkish stance and the dovish stance.

Mixed views on the strength of the US economy

In the United States, some experts argue that the US economy is rapidly weakening. The real GDP of the United States economy has already declined in the first quarter of 2022 from the previous quarter by 0.4 per cent. In addition, the Michigan consumer sentiment index fell to 50 in June from 58.4 in May as consumer confidence eroded owing to high inflation, mainly impacted by gasoline prices. The housing starts in the United States fell by 14.4 per cent in May from April. According to the S&P Global, the flash US Composite Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) Output Index fell to 51.2 in June from 53.6 in May, indicating very weak expansion of current economic activities.

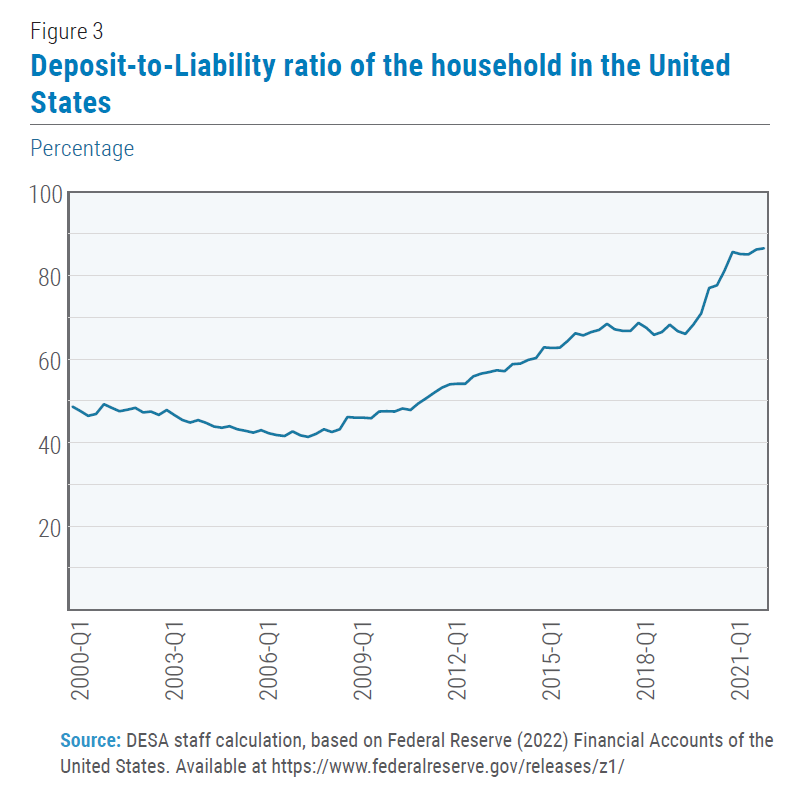

On the other hand, some experts argue that the economy of the United States remains robust. This line of discussion emphasized that the first-quarter GDP contraction was caused by growing negative net exports. Domestic demand continued to grow with 0.5 per cent growth in consumption and 1.8 per cent growth in fixed investment. Moreover, the balance sheet of US households remains solid. For the first quarter of 2022, the US household net worth declined slightly from the previous quarter by $586 billion to $141.1 trillion, but it remains much higher than the historical level. In terms of aggregate disposable income, the level of household net worth remained significantly higher than the previous peak of 2006 and at 773 per cent as of the first quarter of 2022 (figure 2). What is remarkable is the low leverage level of the US household compared to the past. The US household’s deposit-to-liability ratio reached 86.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2022, which is significantly higher than the low of around 42 per cent in the period preceding the global financial crisis in 2007–2008 (figure 3). The jump in the deposits results from high household savings in the stimulus income support packages. Given the low leverage status, the US household may not be impacted by tightening financial conditions as in the past.

On the other hand, some experts argue that the economy of the United States remains robust. This line of discussion emphasized that the first-quarter GDP contraction was caused by growing negative net exports. Domestic demand continued to grow with 0.5 per cent growth in consumption and 1.8 per cent growth in fixed investment. Moreover, the balance sheet of US households remains solid. For the first quarter of 2022, the US household net worth declined slightly from the previous quarter by $586 billion to $141.1 trillion, but it remains much higher than the historical level. In terms of aggregate disposable income, the level of household net worth remained significantly higher than the previous peak of 2006 and at 773 per cent as of the first quarter of 2022 (figure 2). What is remarkable is the low leverage level of the US household compared to the past. The US household’s deposit-to-liability ratio reached 86.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2022, which is significantly higher than the low of around 42 per cent in the period preceding the global financial crisis in 2007–2008 (figure 3). The jump in the deposits results from high household savings in the stimulus income support packages. Given the low leverage status, the US household may not be impacted by tightening financial conditions as in the past.

Mixed views on the labour market in the United States

The labour market in the United States remains very tight. The unemployment rate stood at 3.6 per cent in May 2022, only slightly above the 50-year low of 3.5 per cent recorded in February 2020. The labour market participation rate stood at 62.3 per cent in May 2022, which was still below the pre-pandemic level of 63.4 per cent. The participation rate has been moderately growing over the past several months from the average of 61.6 per cent in 2021.

While the tight labour market induces upward pressures on wage levels, views are mixed on the wage dynamics and their impact on inflation. The average weekly earnings in the United States in the private sector grew by 5.2 per cent in May, which is significantly above the pre-pandemic 10-year average of 2.4 per cent. However, wage growth remains below inflation rates, which suggests that the real income on average has already been declining. This negative income effect may discourage consumption expenditures and weaken inflationary pressures. However, others argue that the current level of wage growth can still develop into a wage-price spiral where inflation expectations are difficult to be contained. In other words, negative income effect alone may not suffice to curb inflation expectations and a wage-price spiral.

While the tight labour market induces upward pressures on wage levels, views are mixed on the wage dynamics and their impact on inflation. The average weekly earnings in the United States in the private sector grew by 5.2 per cent in May, which is significantly above the pre-pandemic 10-year average of 2.4 per cent. However, wage growth remains below inflation rates, which suggests that the real income on average has already been declining. This negative income effect may discourage consumption expenditures and weaken inflationary pressures. However, others argue that the current level of wage growth can still develop into a wage-price spiral where inflation expectations are difficult to be contained. In other words, negative income effect alone may not suffice to curb inflation expectations and a wage-price spiral.

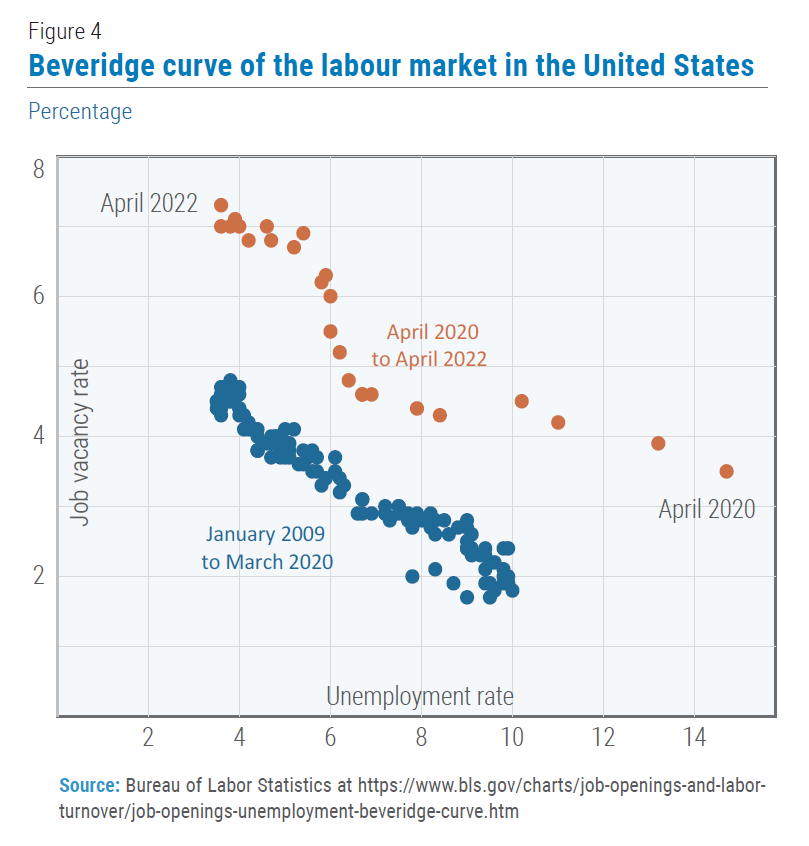

The opinions also diverge on the interpretation of the historically high job vacancy rate, which stood at 7 per cent in April 2022. The Beveridge curve for the US labour market, which plots the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis and the jobs vacancy rate on the vertical axis, shows an outward shift since April 2020 from the long-term trend since January 2009 (figure 4). Some experts argue that the high job vacancy rate can be a reason to hope that a more substantial monetary tightening may not cause a sharp increase in unemployment. This line of argument emphasizes that firms, on average, quit posting job vacancies before laying-off existing workers, facing an economic downturn. However, another line of discussion argues that the outward shift of the Beveridge curve represents a significant decline in job-matching efficiency. In other words, the Beveridge curve may suggest a structural change in the US labour market since the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a situation where conditions for employment (such as qualifications, expertise, geographical location) less likely match employers and job seekers. If the high job vacancy rate represents more structural than cyclical shifts, then the unemployment rate may increase with a high job vacancy rate. It may take time to improve job-matching efficiency with job seekers’ skills and increased mobilities over time.

Implications to developing countries

The outlook on the US economy and its labour market is likely to remain mixed in the near term, which may cause further turbulence in financial markets worldwide. Uncertainties will likely persist, particularly in the bond markets in developed countries, until clear trends in inflation, unemployment, and the economy emerge. The turbulences in bond markets of developed countries are worrying for the developing countries since they impact their financing conditions significantly. The rising interest rates, and the consequent rising financing cost in the US dollar will translate to a higher cost of finance in most developing countries. Having been under multiple adverse external shocks, including COVID-19, global supply chain disruptions, high international commodity prices, and the war in Ukraine, some developing countries remain highly vulnerable. Following Sri Lanka, which defaulted on external debt in April, Lao PDR and Pakistan are in precarious situations facing dire balance-of-payments challenges. The international community must accelerate support for these vulnerable developing countries, particularly the least developed countries, where turbulences in developed countries’ financial markets could negatively affect their financial conditions and growth prospects.

The outlook on the US economy and its labour market is likely to remain mixed in the near term, which may cause further turbulence in financial markets worldwide. Uncertainties will likely persist, particularly in the bond markets in developed countries, until clear trends in inflation, unemployment, and the economy emerge. The turbulences in bond markets of developed countries are worrying for the developing countries since they impact their financing conditions significantly. The rising interest rates, and the consequent rising financing cost in the US dollar will translate to a higher cost of finance in most developing countries. Having been under multiple adverse external shocks, including COVID-19, global supply chain disruptions, high international commodity prices, and the war in Ukraine, some developing countries remain highly vulnerable. Following Sri Lanka, which defaulted on external debt in April, Lao PDR and Pakistan are in precarious situations facing dire balance-of-payments challenges. The international community must accelerate support for these vulnerable developing countries, particularly the least developed countries, where turbulences in developed countries’ financial markets could negatively affect their financial conditions and growth prospects.

Follow Us