UN/DESA Policy Brief #98: Risk-informed finance

Introduction

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the widespread and cascading effects of systemic risks on economies and societies in an increasingly complex and interrelated risk landscape. With more than 2 million lives lost at the time of writing, the spread of COVID-19 and its economic fallout are an urgent call for the global community to better prepare for and reduce the risk of catastrophic events.

Disasters are often the result of decades of accumulation of risk. Risk that has not been sufficiently addressed, such as high debt and excess leverage, poverty and inequality, infrastructure that is not resilient, and climate change, will continue to derail financing and progress of the SDGs. Reducing and better managing these risks is indispensable to achieving the SDGs. At the same time, investment in the SDGs would help reduce vulnerabilities. For example, investments in social protection systems, which can be ramped up in time of need, can help vulnerable groups, households and societies manage risk and volatility, and protect them from poverty in the event of a crisis.

The case for such investments is clear. Yet, they do not happen at the required scale. Short-term costs of investments often loom larger than uncertain long-term benefits. Investments in prevention and resilience have a public good character, and like many public goods, they are underfunded. To address this, policymakers need to mainstream risk management in all policies, processes and decisions, and create incentives for risk reduction and investments in and aligned with the SDGs.

A risk and resilience framework

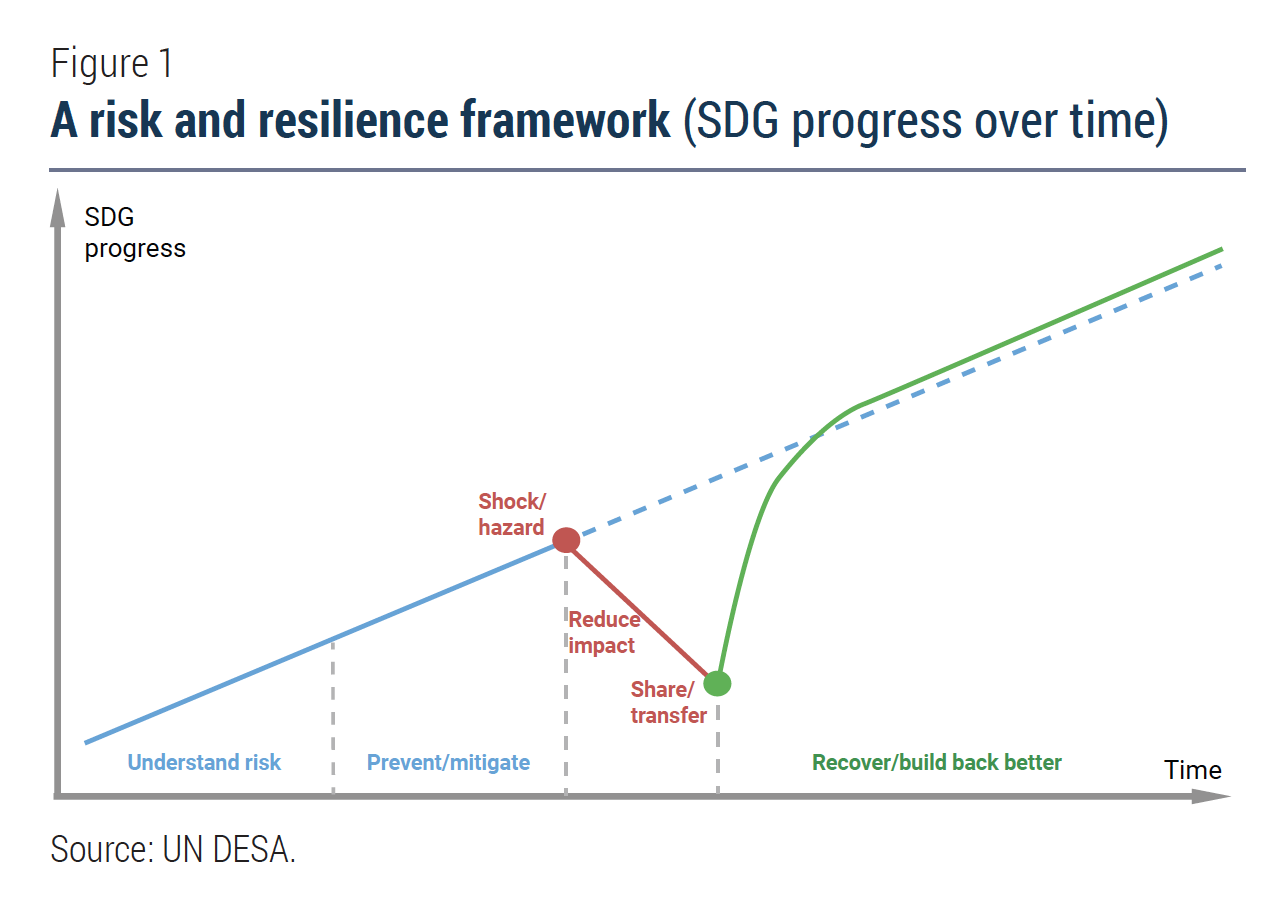

The COVID-19 pandemic and climate change are both manifestations of growing systemic risks—risks that have widespread, cascading effects across geographies and economies. Conventional risks (i.e. the risk of isolated events, such as technological or operational risks associated with an infrastructure investment) can be managed through traditional risk management techniques. These include: a risk assessment; measures to reduce the probability and impact or cost of a shock (such as by strengthening the legal and regulatory environment); and sharing or transferring risk to those better able to manage it (in particular through insurance or other measures that diversify risks).

Global systemic risks, on the other hand, are difficult or impossible to diversify or insure – and few countries can mitigate these risks on their own. To prepare for these risks, Governments also need to invest in resilience to strengthen the overall ability of the economy and society to withstand shocks and recover. Resilience strategies consider how to: (i) withstand crises and recover quickly from shocks; and (ii) learn from crises, adapt to new conditions, and rebuild better. As figure 1 illustrates, a risk and resilience framework should thus include steps to: better understand risk, prevent shocks where possible, reduce their impact and share or transfer residual risks, and efforts to build back better. Risk can never be completely eliminated, nor is that always desirable, as risk is often associated with opportunity.

Global systemic risks, on the other hand, are difficult or impossible to diversify or insure – and few countries can mitigate these risks on their own. To prepare for these risks, Governments also need to invest in resilience to strengthen the overall ability of the economy and society to withstand shocks and recover. Resilience strategies consider how to: (i) withstand crises and recover quickly from shocks; and (ii) learn from crises, adapt to new conditions, and rebuild better. As figure 1 illustrates, a risk and resilience framework should thus include steps to: better understand risk, prevent shocks where possible, reduce their impact and share or transfer residual risks, and efforts to build back better. Risk can never be completely eliminated, nor is that always desirable, as risk is often associated with opportunity.

All investing implies a degree of risk-taking – indeed most innovation is linked to active risk-taking. Underinvestment in the SDGs thus implies a lack of risk-taking in SDG-related areas, by both the private and public sectors (e.g., through public development banks). The identification of origins and impacts of key risks (and opportunities) can thus help determine appropriate financing policy responses, including who is best placed to take action. The 2021 Financing for Sustainable Development Report lays out a risk categorization that can help policymakers determine appropriate policy actions.

Risk-informed sustainable finance for development

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed and highlighted weaknesses and blind spots in both public and private investment and financial management. It has also highlighted underinvestment in resilience and sustainability. Indeed, a risk-informed approach to financing for development should aim to ensure not only that: (i) financing is sustainable, risk-informed, and resilient, but also that (ii) sustainability, risk reduction and resilience are sufficiently financed.

The public sector

Risk management is a central aspect of traditional public financial management. It aims to ensure the sustainability of public balance sheets and macro fiscal frameworks in light of fiscal risks such as disasters, macroeconomic shocks, contingent liability risks, and others. The primary objective is to stabilise economic activity and public service delivery in the short run, and to promote economic growth and sustainable development over the longer term. Nonetheless, the capacity to manage fiscal risks is limited in many countries. Developing countries in particular are exposed to a range of risks that can have significant macroeconomic and fiscal impacts.

Addressing these risks more thoroughly and effectively to build resilience into public budgets requires several actions by policymakers:

First, incorporate risk analysis into planning processes. Countries tend to allocate significantly more funding for (ex post) crisis response than to (ex ante) risk reduction. Integrated National Financing Frameworks (INFFs) that, for example, incorporate medium-term revenue strategies into planning processes, can help policy makers better understand and plan for such risks and overcome this ex post bias in policy.

Second, use a multi-instrument approach to fiscal risk management, including policies aimed at prevention (e.g., strengthening the enabling environment to reduce investment risks), reducing risk impact, and using insurance and other risk-sharing mechanisms, to respond to the various characteristics of these risks.

Third, risk-informed debt management is needed, both at the national and international level. Fiscal risk is intrinsically linked to sovereign debt management and debt sustainability. For example, state contingent debt instruments could increase the resilience of sovereign balance sheets. The official sector could take a lead by including state-contingent elements in public sector lending.

Public actors should also ensure sufficient investments in prevention and resilience which is often lacking - partly due to lack of knowledge, partly due to poor incentives, including short-term horizons. Yet, the public sector is the risk bearer of last resort: it is already implicitly taking on many SDG-related risks, even when they are not visible on current public balance sheets. When a crisis occurs, private risks often become public liabilities—such as during a financial crisis, when the public sector bails out the banking sector to limit contagion to the broader economy, or covering the cost of reconstruction following a natural hazard.

Public policy also shapes the risk landscape for investors and other stakeholders, and it is up to policymakers to ensure that incentives are well aligned with SDG-relevant risks (e.g., through carbon pricing and disaster risk disclosure).

In some cases, it can be advantageous for the public sector to actively seek risks associated with transformative investments in infrastructure, innovation or related areas precisely because these investments may lower risks in the future. For example, investments in innovation are associated with high levels of uncertainty and risk—sometimes too large for private investors to take on—but can have extremely high social returns. There are thus calls for better utilizing development bank balance sheets, and more active risk taking by public development banks. Governments can also share investment risks with private investors.

Private business and investors

Private businesses and investors routinely assess risks relative to financial returns. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed underlying corporate vulnerabilities to systemic risks – driven by high leverage, complex, just-in-time supply chains, and the impact of climate and other non-economic risks on financial returns. While climate risks are increasingly being considered by investors with sufficiently long investment time horizons, many SDG-related risks are too far off to be considered by most investors. And most SDG-related risks are not being properly measured, leading to their underestimation. Full disclosure of those risks is a precondition for risk-informed behaviour.

While management of material risks is a routine, if challenging, part of investing, financing for sustainability and resilience is not. Most private investors aim to maximise financial returns, and do not consider how their behaviour impacts SDG factors that do not directly and materially impact profitability (e.g., externalities, such as the impact of plastic on the environment). Risk informed financing policies must thus go beyond efforts to evaluate material risks—to also understand, disclose and ultimately price or otherwise account for all other SDG impacts. Only then will commercial investments internalise the impact of their activities on the SDGs, and investors’ preferences fully align with sustainable development. Public policy thus needs to encourage changes in business behaviour, such as through carbon pricing, regulation, and other measures, as laid out in the The 2021 Financing for Sustainable Development Report.

International support and action

International support can both directly support sustainability and resilience of public finances and financial systems, and also contribute to financing for risk reduction, resilience and sustainability.

First, international action and agreement is needed to mitigate systemic risks, such as climate related shocks, or financial market spill-overs. In addition, international public finance can provide fiscal support in times of macroeconomic shocks, crises and disasters, and thus play a countercyclical role in enhancing resilient public financing. Multilateral development banks in particular have historically been able to provide countercyclical financing. The international community has also set up or supports a range of quick-disbursing financing instruments that provide rapid fiscal support in the event of a disaster or pandemic. Strengthening the global financial safety net and increasing IMF capacity for concessional lending and provision of liquidity support (e.g., through a substantive issuance of special drawing rights in response to the COVID-19 pandemic) remain a priority.

Development cooperation can support developing countries in monitoring and addressing risk and building resilience, including by strengthening national capacities and country systems that are able to respond to shocks and crises. Government capacity has been a key determining factor of the effectiveness of countries’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Development cooperation has a key role to play in building such capacities—in national health systems, social protection systems, or crisis response systems, for example. INFFs could serve as a tool to align such international support with national priorities and needs. Financing mechanisms can be designed to further support rapid and effective national crisis response, addressing country-specific challenges and opportunities.

Both climate mitigation and the COVID-19 pandemic provide stark illustrations for the need for international cooperation, and for provision of support to developing countries with limited resources, not only in the spirit of global solidarity, but also in the self-interest of advanced countries. This entails not just additional financing, but also strengthened and more inclusive global governance, and increasing the voice of the most vulnerable groups and countries—those with the least agency to reduce global risks but most vulnerable to shocks and disasters.

Follow Us