UN/DESA Policy Brief #72: COVID-19 and sovereign debt

Introduction

Introduction

Without aggressive policy action, the COVID-19 pandemic could turn into a protracted debt crisis for many developing countries. Debt risks in developing countries were already high prior to the pandemic. These risks are now materializing. High debt servicing hamstrings developing countries’ immediate response to COVID-19 and rule out needed investment in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A debt crisis would dramatically set back sustainable development.

The global community has responded. Partial debt service suspensions were offered to 76 low-income developing countries eligible to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) — which includes all least developed countries (LDCs) and 13 small island developing States (SIDS). The IMF also offered further debt service relief to 25 of the poorest countries.

But actions taken so far will not suffice to avoid defaults. Multilateral and commercial debt are excluded from debt service suspension for all countries, and many middle-income countries at risk are entirely excluded from the initiative. Debt relief — which many developing countries will eventually need if they are to recover and progress toward the SDGs — is not on the table.

Addressing sovereign debt distress is a long-standing challenge. While there is no shortage of policy ideas, progress in addressing the challenge has remained piecemeal, with little appetite among key actors — including public and private creditors and some debtors — to design a comprehensive approach. This has left the world ill-prepared for the current crisis.

A three-pronged approach will be needed, in line with the Secretary-General report, “Debt and COVID-19: A Global Response in Solidarity”: (i) a full standstill on all debt service (bilateral, multilateral and commercial) for all developing countries that request it, while ensuring that developing countries without high debt burdens still have access to credit needed to finance Covid responses; (ii) additional debt relief for highly indebted developing countries to avoid defaults and create space for SDG investments; and (iii) progress in the international financial architecture, through fairer and more effective mechanisms for debt crisis resolution, as well as more responsible borrowing and lending. This note provides some initial concrete ideas to advance proposals made by the Secretary-General.

This approach fulfils long-standing commitments in the Financing for Development outcomes. It builds on the Addis Ababa Action Agenda’s call for debt restructurings to be fair, orderly, timely and efficient, and give room for countries to invest in the SDGs.

The impact of COVID-19 on the sovereign debt of developing countries

COVID-19 and its economic fallout are devastating to public balance sheets. Countries are faced with additional spending needs to finance the immediate health response, provide support to households and firms, and invest in the recovery once the pandemic is under control. At the same time, revenues are collapsing, particularly for commodity exporters and tourism and other services-dependent countries. Global public debt stocks are projected to jump by 13 percentage points of gross world product in just one year, from 83 to 96 per cent (IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2020). The IMF expects fiscal balances to turn sharply negative in developing countries, to -9.1 and -5.7 per cent of GDP in middle-income and low-income countries, respectively.

Vast additional public borrowing will have to be financed in a context of significant capital outflows from developing countries and rising financing costs. Non-resident portfolio outflows from emerging market countries amounted to almost $100 billion since 21 January (IIF, 2020). Despite near zero global interest rates, borrowing costs for most developing countries have risen: credit spreads on emerging market sovereign bonds more than doubled from the beginning of the year to April, widening to more than 600bps. Over 100 countries have asked the IMF for emergency funding from its Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI).

This is exacerbating already high debt risks…

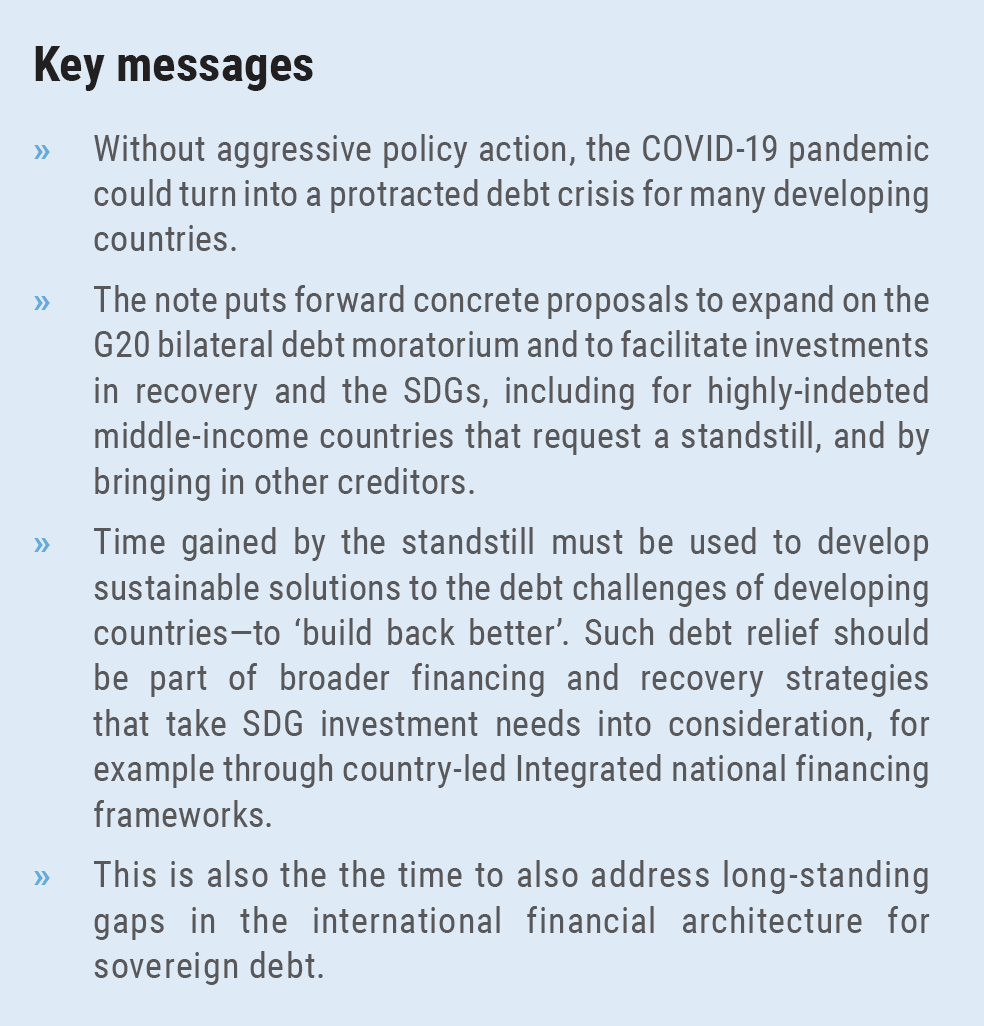

Debt risks had been rising for a decade, making developing countries vulnerable to shocks. As highlighted in the 2020 Financing for Sustainable Development Report, developing countries entered the 2009 financial crisis with moderate debt. Since then, low global interest rates and greater access to financing contributed to record global debt, and to a broad-based build-up in public debt in developing countries — including across least developed countries (LDCs), small island developing States (SIDS) and middle-income countries (MICs) (see Figure 1) (United Nations, 2020). Median public debt in developing countries grew almost 15 percentage points of GDP from 2012 to 2019 (from 35 per to 51 per cent of GDP).

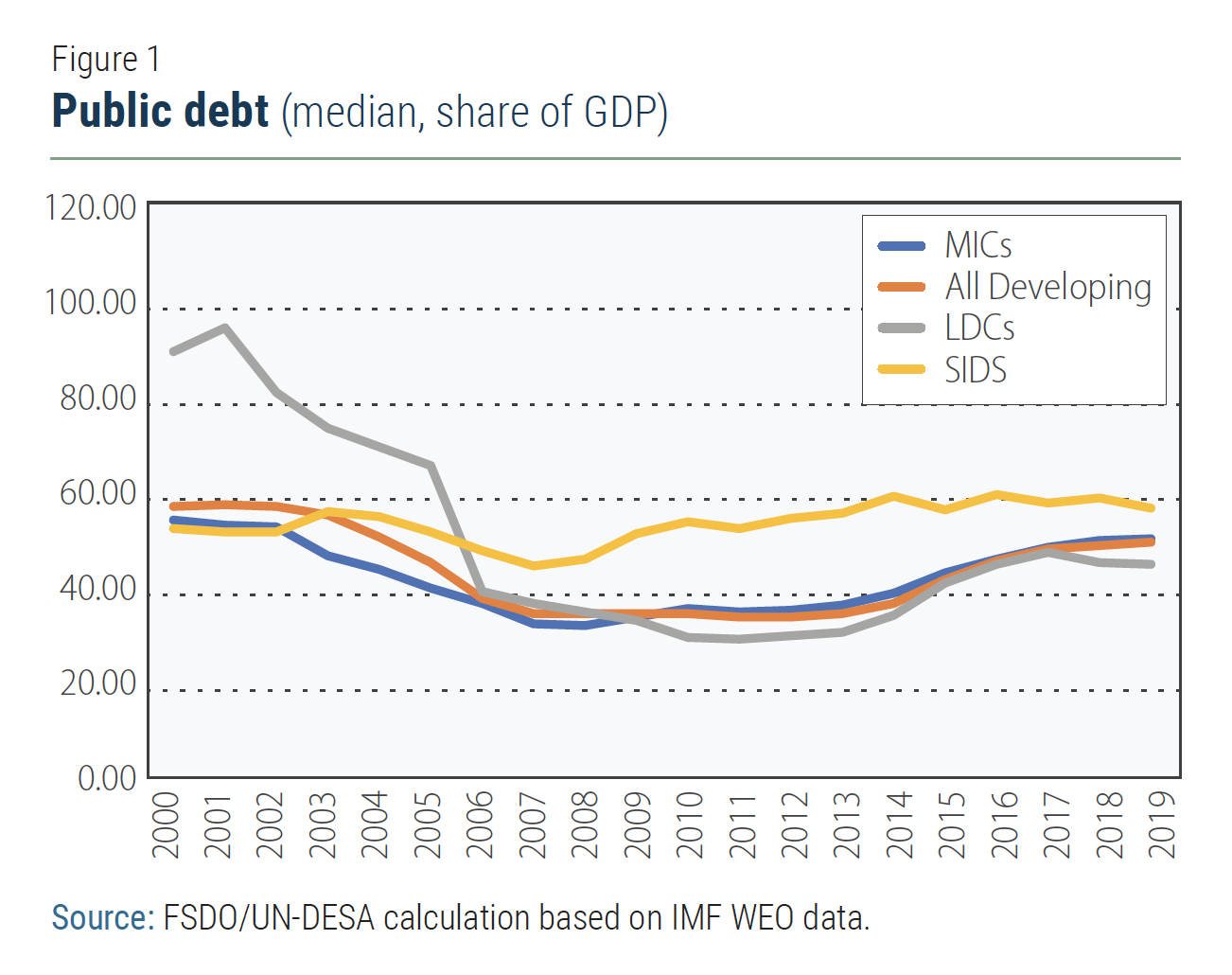

LDCs and other low-income countries increasingly tapped non-traditional sources of credit. Funding from non-traditional bilateral creditors and international bond markets provided poor countries with access to much needed resources to finance investments in the SDGs, but also raised risks. While official debt remains the most significant portion of the external debt of most IDA-eligible low-income developing countries (those countries eligible for the G20 bilateral debt moratorium), commercial credit increased more than three-fold from 2010 through 2019, rising from 5 to 17.5 per cent (see Figure 2). The increase was particularly pronounced in so-called “frontier economies” (low-income and least developed countries with international bond issuance). Thirty-eight per cent of these countries’ external public debt is owed to private creditors, with 32 per cent in bonds.

LDCs and other low-income countries increasingly tapped non-traditional sources of credit. Funding from non-traditional bilateral creditors and international bond markets provided poor countries with access to much needed resources to finance investments in the SDGs, but also raised risks. While official debt remains the most significant portion of the external debt of most IDA-eligible low-income developing countries (those countries eligible for the G20 bilateral debt moratorium), commercial credit increased more than three-fold from 2010 through 2019, rising from 5 to 17.5 per cent (see Figure 2). The increase was particularly pronounced in so-called “frontier economies” (low-income and least developed countries with international bond issuance). Thirty-eight per cent of these countries’ external public debt is owed to private creditors, with 32 per cent in bonds.

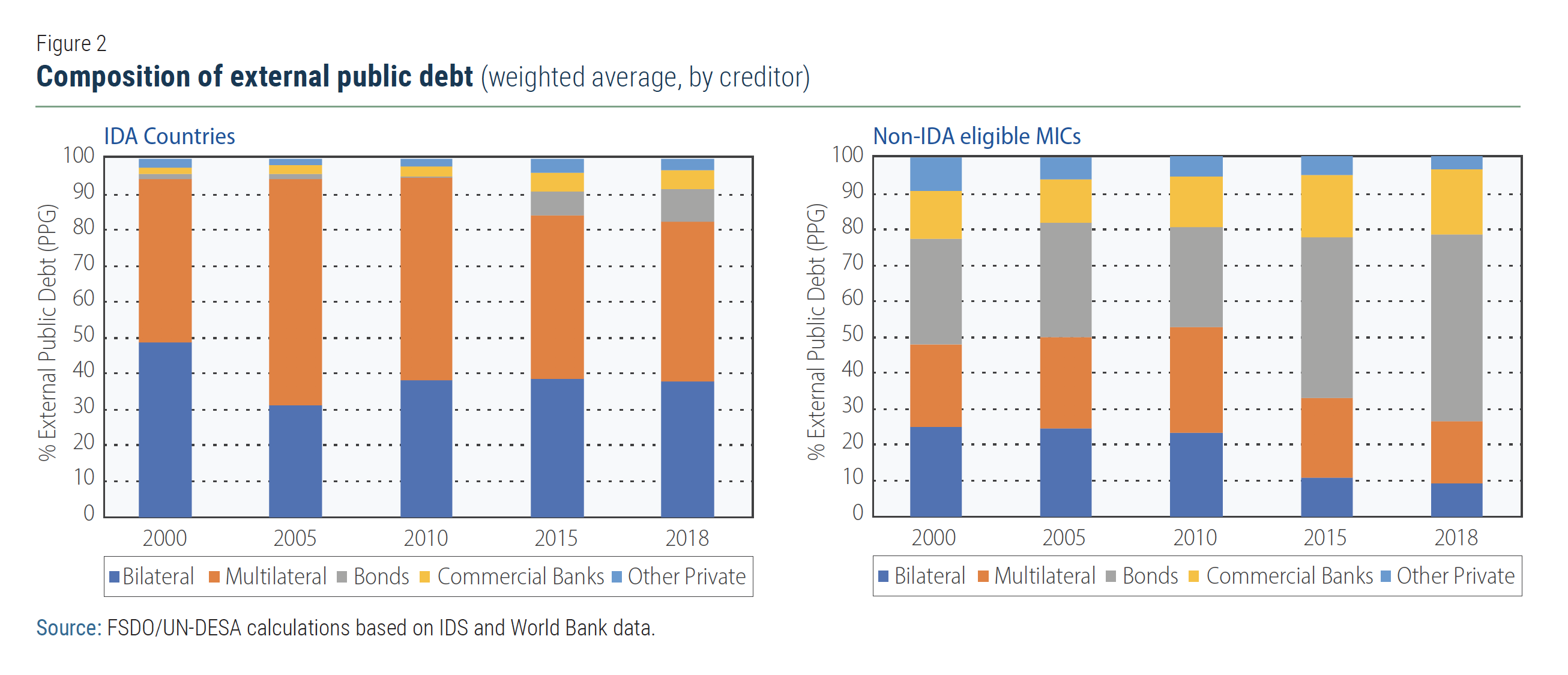

Debt servicing cost and refinancing risks remain high. Debt servicing costs for IDA-eligible countries more than doubled between 2000 and 2019, increasing from 6 to 13 per cent of government revenue (see Figure 3). The G-20 moratorium will provide meaningful “breathing space” to many of the poorest countries, as most of their debt is from official sources. On the other hand, for “frontier economies”, commercial debt accounts for an average of 25 per cent of public revenues. These countries will have to refinance more than USD 5 billion annually of Eurobonds over the next years. This would have been extremely difficult even before the outbreak of the pandemic, but will not be possible if the crisis is prolonged.

The debt moratorium provides much needed breathing space but does not address solvency concerns in many of the poorest countries. Almost half of IDA-eligible low-income countries — 36 countries — were already considered at high risk of or in debt distress at the end of 2019. With so many countries already facing solvency issues, a moratorium on debt service alone will not prevent widespread debt crises. Many middle-income countries excluded from current policy actions are also vulnerable. In the low global interest rate environment, public debt (particularly international bond issuance) increased steeply in the last decade in middle-income countries, rising to 54 per cent of GDP in 2019, from 37 per cent in 2010 (Figure 2). Debt servicing costs consume almost a quarter of public revenues in the median middle-income country (Figure 3). Middle-income countries also saw a build-up in private sector borrowing, which is largely denominated in US dollars outside of China, further increasing their vulnerability to capital flow reversals and currency crises now unfolding.

Many middle-income countries excluded from current policy actions are also vulnerable. In the low global interest rate environment, public debt (particularly international bond issuance) increased steeply in the last decade in middle-income countries, rising to 54 per cent of GDP in 2019, from 37 per cent in 2010 (Figure 2). Debt servicing costs consume almost a quarter of public revenues in the median middle-income country (Figure 3). Middle-income countries also saw a build-up in private sector borrowing, which is largely denominated in US dollars outside of China, further increasing their vulnerability to capital flow reversals and currency crises now unfolding.

Middle-income countries are a heterogenous group—some have low debt levels and should continue to have access to markets. There are 15 middle-income countries with high credit ratings that should continue to be able to access markets. For example, Panama was able to issue a sovereign bond in the international market at the end of March. The priority for these countries is to prevent a generalized freeze of capital flows.

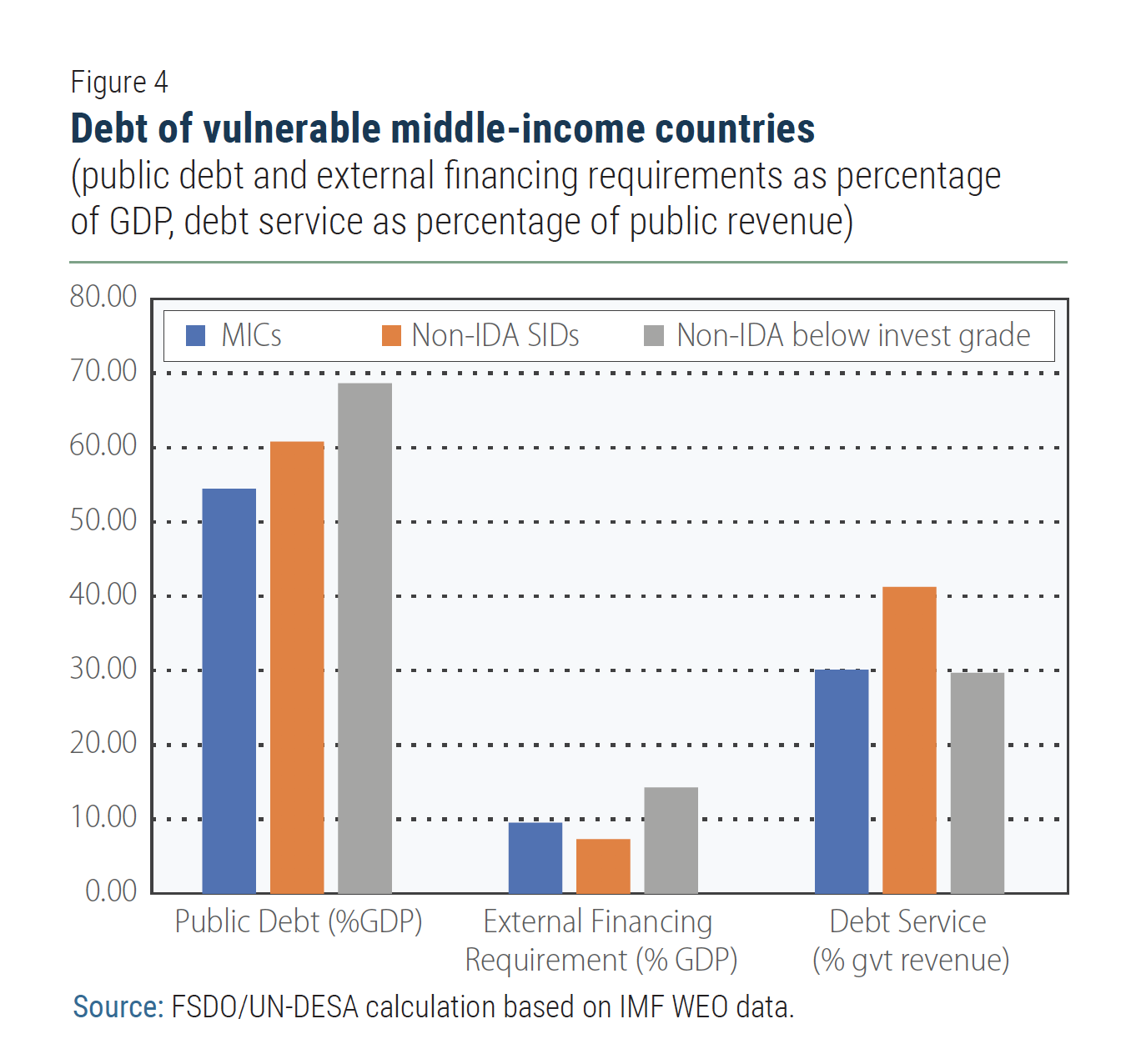

But other middle-income countries excluded from current relief efforts may find it impossible to service or rollover debt. Thirty-seven middle-income countries are rated below investment grade by major ratings agencies, and several are already in debt distress. Their external financing requirements average more than 14 per cent of GDP (Figure 4), with 63 per cent from commercial creditors and 38 per cent in international bonds. Six middle-income small island developing States that are not eligible for debt suspension under the G-20 initiative have especially high public debt and debt service burdens, at over 40 per cent of revenue on average. More than half of external public debt in the six SIDS is owed to commercial creditors, mostly through bonds. Any debt service moratorium or relief to meaningfully address these countries’ challenges would have to include commercial creditors.

But other middle-income countries excluded from current relief efforts may find it impossible to service or rollover debt. Thirty-seven middle-income countries are rated below investment grade by major ratings agencies, and several are already in debt distress. Their external financing requirements average more than 14 per cent of GDP (Figure 4), with 63 per cent from commercial creditors and 38 per cent in international bonds. Six middle-income small island developing States that are not eligible for debt suspension under the G-20 initiative have especially high public debt and debt service burdens, at over 40 per cent of revenue on average. More than half of external public debt in the six SIDS is owed to commercial creditors, mostly through bonds. Any debt service moratorium or relief to meaningfully address these countries’ challenges would have to include commercial creditors.

Policy recommendations

Policy recommendations

First, debt service payments must be suspended to provide countries with fiscal space to respond to the crisis: The 2020 Financing for Sustainable Development Report called on official creditors to suspend debt payments from least developed countries and other developing countries that request forbearance without delay. The G20, including its non-Paris Club members, have now committed to do so for IDA-eligible countries through the end of 2020. Given the breadth of the crisis, these actions need be extended in several ways:

- The debt standstill should be offered to all highly-indebted developing countries that request it, including middle-income countries. It should be clear, however, that this is not a call for universal forbearance for all middle-income countries. Countries that still have access to financial markets should continue to make use of them, to avoid a generalized freeze in capital flows to developing countries. A global asset purchasing programme, which could for example be funded by a Special Drawing Rights issuance, or partial guarantees could be explored to support market access.

- Debt to international financial institutions should be included in the standstill. Because the standstill is offered on a net-present-value-neutral basis, with creditors fully repaid, multilateral creditors should be able to do so without significantly impacting their AAA credit ratings. Shareholders should support them, in order not to threaten their ratings or curtail their ability to provide fresh financing. Indeed, rapid access to fresh concessional financing, as provided by the international financial institutions, will remain critical.

- Private creditors must join the debt moratorium to avoid the public sector bailing out private creditors. They should do so on comparable terms, with details of those terms to be worked out in consultation with debtors. It is ultimately in commercial creditors’ collective interest to do so, as providing a moratorium today will allow countries to repay the debt in full in the future. As there is no established mechanism to guarantee full private sector participation, creative solutions will be needed. One proposal is for the official sector to establish a central credit facility for countries requesting assistance, managed by an international financial institution, to coordinate a standstill. Debtor governments would make all payments coming due during the relevant period to the facility, which would initially fund crisis response measures and later be used to repay creditors (Bolton et al, 2020). The facility would be considered senior to other debt due to official sector involvement, so that creditors participating would be repaid before those that do not participate. Jurisdictions that govern developing country sovereign bonds issuance could also halt lawsuits by non-cooperative creditors when debt payment suspensions have been agreed. There is precedent for such action: the UK, which governs the vast majority of commercial debt of countries currently included in the standstill, limited the ability of creditors to seek recovery of full value of debt by countries benefiting from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative through its 2010 Debt Relief Act.

Second, debt relief will be needed to avoid widespread defaults and to facilitate investments in recovery and the SDGs. A moratorium will not suffice for many highly indebted countries. The IMF’s cancellation of debt service payments for the 25 most vulnerable countries for the next 6 months must be followed by more comprehensive action by the international community, including relief from all creditors. This includes revisiting debt sustainability and SDG achievement, which will need to be reassessed in a comprehensive manner after the COVID-19 shock.

- For countries which are highly indebted but do not have unsustainable debt burdens, debt swaps could be considered. Such debt-to-Covid/SDG swaps could be modelled on experiences from debt-to-health and debt-to-climate swaps, and would channel planned debt service payments into SDG investments. This could include swapping outstanding debt into Covid/SDG bonds, for which standards could be developed.

- Official creditors could exchange debts to apply more concessional terms and reduce debt service in the short run, and better share risks with vulnerable debtors in the medium-term. For example, official creditors could apply IDA-terms to their current and future credits to least developed and other vulnerable countries, extending grace periods, lengthening average maturities and lowering average interest costs (Lee, Morris, Gardner and Sami, 2020.). They could also systematically include relevant state-contingent elements—for terms of trade shocks, disasters, or others—to help countries better manage future shocks.

- A significant number of countries will need a reduction of payments. The Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and multilateral debt relief initiative (MDRI) provide the historical precedent of writing down debt to sustainable levels to provide space for development investments for low-income countries to invest in development. Those least developed countries, other low-income countries, and small island developing States that are not judged to have sustainable debt levels after the pandemic should be eligible for official debt relief.

- Any debt relief should be part of a broader strategy that takes SDG investment needs into consideration. The assessment of relief required should consider medium-term financing gaps for the SDGs (rather than short-term liquidity constraints only) and inform comprehensive financing strategies to close them, e.g. in the context of integrated financing frameworks. The United Nations, through the Inter-agency Task Force, can continue to work on these questions.

- Debt relief must seek comparable treatment for private creditors. Private debt restructurings may sometimes be challenging, but debtors could make creative use of collective action clauses and other developments in bond markets since the early 2000s. A fund to buy back outstanding stock of external public debt issued on commercial terms could also be considered, similar to the Debt Reduction Facility accompanying HIPC.

- Official contributions to finance such write-downs should not crowd out other ODA spending. Other innovative financing alternatives could be considered.

Third, the current crisis highlights gaps in the current international sovereign debt restructuring architecture that should be addressed once the world recovers from COVID-19. No comprehensive mechanism exists to restructure sovereign debt. As the debt landscape has grown in complexity, restructurings have become ever more complicated. Existing mechanisms should be revisited, based on principles spelled out in the Addis Agenda of timely, orderly, effective, and fair resolutions; shared responsibilities; and restoring public debt sustainability to enhance the ability of countries to achieve the SDGs. Options that could be considered include:

- Continued improvements to market-based approaches, such as improved contractual terms and greater use of state-contingent debt instruments (such as linking future payments to GDP growth, or hurricane clauses), including by official creditors;

- Extension of national legislation to limit litigation by uncooperative creditors;

- Further development of soft law principles, including both principles for fair restructuring and for responsible borrowing and lending to prevent debt crises, and their increasing use by adjudicative bodies—national courts, for example—to guide decision-making;

- A Sovereign Debt Forum, which would provide a platform for discussions between creditors and debtors, in the context of the SDG debt relief initiative. It could facilitate further steps such as: agreements on voluntary stays; coordinated rollovers such as in the Vienna Initiative; and other measures.

The UN, which is not itself a creditor, provides a neutral forum for inclusive dialogue among sovereign debtors and creditors and other stakeholders to discuss a way forward.

Follow Us