UN/DESA Policy Brief #66: COVID-19 and the least developed countries

Covid-19 threatens to undo progress achieved towards sustainable development by the least developed countries (LDCs) over recent decades. Even before the current crisis, LDCs were unlikely to achieve the SDGs, which emphasizes as a core principle “leaving no one behind”, including the most marginalized countries. Any further obstacles mean the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will almost certainly be missed without far-reaching policy responses. This Policy Brief reviews some of the main health, social and economic impacts of Covid-19 on LDCs and makes a series of policy recommendations.

Covid-19 threatens to undo progress achieved towards sustainable development by the least developed countries (LDCs) over recent decades. Even before the current crisis, LDCs were unlikely to achieve the SDGs, which emphasizes as a core principle “leaving no one behind”, including the most marginalized countries. Any further obstacles mean the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will almost certainly be missed without far-reaching policy responses. This Policy Brief reviews some of the main health, social and economic impacts of Covid-19 on LDCs and makes a series of policy recommendations.

Underdeveloped health systems

As of 28 April 2020, the World Health Organization reported 16,469 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 472 deaths in LDCs, affecting all but six LDCs. Together, LDCs account for a small but rising 0.56 per cent of global cases and 0.23 per cent of global deaths. But these low figures do not reflect the true picture: a low rate of reported infections is often the consequence of LDCs’ lack of testing capacity.

Once the new coronavirus spreads within an LDC, prospects are dire. Covid-19 is overwhelming public health systems even in many developed countries. It will almost certainly wreak havoc in countries with underdeveloped health systems. There are on average only 113 hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants in LDCs, less than half the number in other developing countries and around 80 per cent below developed countries. Even the most basic public health interventions like frequent handwashing are impossible for many people in LDCs. LDCs that had closed their borders as part of containment measures risk infection as they allow people to come in from overseas to provide assistance and technical “know-how”.

Lockdown to save lives

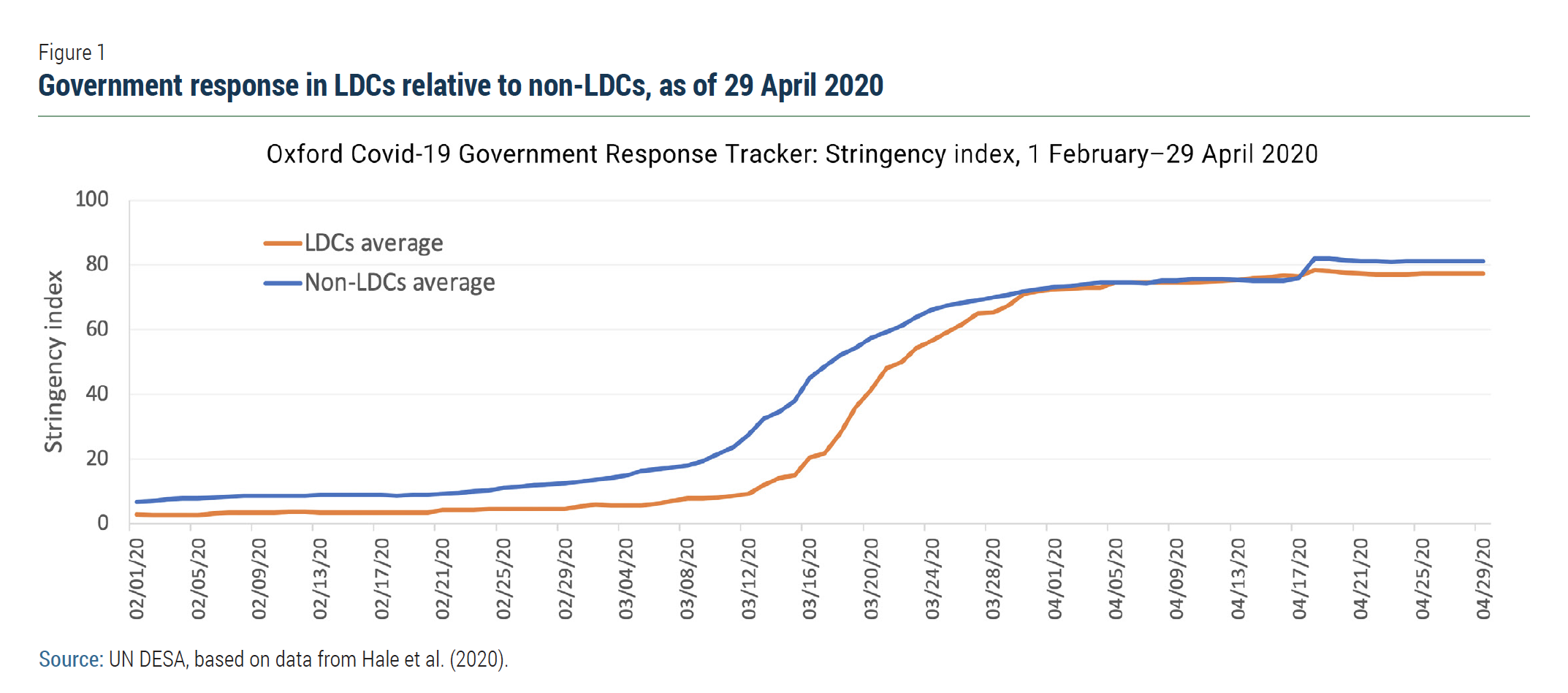

To limit the spread of the new coronavirus, LDCs have resorted to similar measures to other countries: imposing states of emergency, prohibiting public gatherings, closing schools and universities, banning international and often also domestic travel, and closing non-essential businesses. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker reports as of 29 April restrictive measures in 26 LDCs, with Djibouti and Rwanda scoring at maximum stringency. Measures in LDCs remain slightly less restrictive than in other countries (see Figure 1). Additional LDCs not included in the tracker, such as those in the Pacific, have also imposed travel restrictions and social distancing. These measures save lives but also force economies into recession.

There is no real alternative. A strategy of “testing, tracing and isolating”, which would allow economies to operate with minor interruptions by restricting only the people actually infected or those who have been in close contact with them, has proven unfeasible for most countries. LDCs lack not only the necessary testing capacities, but the technologies and governance structures to effectively and efficiently trace and isolate the infected. A herd immunity strategy would stop the spreading sooner but would cost many lives and cause social devastation. Hoping that effective vaccines or medicines will be available soon is widely seen as untenable.

Suppressing the spread of the coronavirus through lockdowns and milder forms of social distancing are far more difficult to implement in LDCs, in particular in slums or in refugee camps. Whereas developed and more advanced developing countries are able to shift at least some production to employees’ home offices, the differ

ent types of jobs and the lack of information technology infrastructure makes working from home impossible for most people in LDCs. Many vulnerable populations in LDCs lack access to a social protection system, so that the economic lockdown necessary to save lives will immediately increase poverty, hunger and destitution. Among those most exposed to the immediate social impacts of Covid-19 are young people, and in particular young women, who tend to be overrepresented in LDCs’ sizeable informal economies, lack access to savings, and work in the economic sectors that have been most impacted by social distancing restrictions.

Some of the longer-term risks of lockdowns may also be more severe in LDCs. Existing economic, gender and social inequalities are exacerbated. Combined with a loss of household income, millions of women are confined with their abusers, with limited options for help and support. The unequal distribution of unpaid care and domestic work increases because women and girls spend even more time than men and boys performing these care activities—a significant barrier to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. Extended school closures could have more drastic effects on human capital, particular for girls and young women, and therefore future economic growth due to the impossibility of remote schooling.

Collapse of global demand

Most LDC economies rely on external demand. Successful integration into the global economy brought many LDCs closer towards graduation from the LDC category, whether through tourism, light manufacturing, remittances from workers abroad or oil and other commodity exports. With the increasing number of LDCs using trade and services as an engine for growth, the expected collapse in world trade could have a lasting impact.

Manufacturing, in particular of garments, has been a main development driver for LDCs approaching graduation, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, or Myanmar. These countries benefit not only from low production costs and effective domestic policies supporting the sector, but also from trade preferences in most developed and major developing markets. Covid-19 has caused a demand shock through a massive cancelation of orders as fashion retail in developed countries collapsed. At the same time, the garment sector is undergoing a domestic supply shock caused by mandated factory closures. Already at the end of March 2020, a quarter of the 4 million mostly female Bangladeshi garment workers had been fired or furloughed. In the first half of April 2020, garments exports from Bangladesh declined by more than 80 per cent on a year-to-year basis

Tourism is the main export of many LDCs, particularly small island developing States (SIDS). Travel restrictions and advisories by authorities in foreign tourist markets, as well as the income loss of consumers in these markets, have reduced demand, sometimes almost completely. As in the case of garments, the demand collapse is paralleled by the collapse in domestic supply caused by travel restrictions imposed by recipient countries limiting tourist inflows.

Reduced demand for migrant workers and travel bans imposed by receiving or sending countries will drastically reduce remittances, which are essential in many LDCs. The return of migrant workers who have lost their jobs due to the crisis abroad can put further stress on limited social protection and health systems.

Commodity exporters have been hit by reduced demand and resulting price declines. Oil exporting LDCs are additionally affected by disagreement among major oil exporting countries on how to stabilize prices, with recent oil prices plunging 50 per cent. While other commodities have been less affected than oil, prices for most metals and minerals have declined by 20 per cent, slashing export earnings and potentially reducing foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows.

Health crisis and slump in global demand swell beyond initial impact

Domestic lockdown and global demand shocks are already having a massive impact. A decline in domestic incomes and economic interdependence may impact sectors that remain at first unaffected, causing additional economic hardship. For instance, even if the transportation sector is exempt from lockdowns and ports remain open, additional controls and decline of auxiliary services will hamper trade and the distribution of goods. This risks worsening food insecurity, particularly in urban areas, where food prices are already increasing. These types of vulnerabilities are exacerbated by the lack of resources in LDCs (both financial and institutional) to compensate for the income losses of firms and households.

Currently, Covid-19 is a health and economic crisis. If firms and households start defaulting on payments and loans, the pandemic risks turning into a financial crisis, which can be contagious, as the recession in 2008 showed. While the global financial system should be better prepared than in 2008, it remains to be seen if it can withstand pressures caused by prolonged global economic stress.

Pressure on exchange rates from an export slump creates balance of payments problems. Due to the strengthening of foreign currencies in which external debt of LDCs is denominated, pre-existing debt problems intensify. Already before the Covid-19 crisis, 19 out of 39 LDCs covered by the debt sustainability assessment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for low income countries were at high risk of, or already in, debt distress.

The overall economic impact remains highly uncertain

Preliminary forecasts from the World Economic Situation and Prospects as of mid-2020 point to a global recession with a 3.1 per cent decline in global GDP. LDCs are expected to grow by only 0.8 per cent in 2020, followed by a strong rebound of 4.6 per cent in 2021. However, given the massive downside risks, far more negative and lasting outcomes are plausible. Evidence from the 2008 global financial crisis indicates that it took more than five years for LDCs, particularly small island LDCs, to recover from the then completely external demand shocks.

Policy responses

The unprecedented economic crisis in LDCs caused by the coronavirus requires decisive and swift action, both by affected countries and by international development partners, who could create a targeted package of international support measures.

Support public health systems

As LDCs often lack the productive capacity and financial resources to obtain necessary health equipment, they need immediate support from the international community, in addition to support for the long-term strengthening of the health sector. All governments should refrain from restricting exports of essential medicines and health equipment, while vulnerable countries need to ease existing import restrictions. Marginalized countries stand to benefit from increased global efforts to develop vaccines and effective medications against Covid-19. Such efforts should consider vaccines as global public goods and ensure they will reach the most vulnerable first.

Support affected households and businesses

In addition to increasing budget allocations for the health sector, most LDCs have already adopted or are developing programs and measures to provide income or food support to their unemployed and vulnerable populations. Unfortunately, this is far more difficult than in advanced economies, as social protection systems are often lacking. Even where they exist, they often fail to reach workers in the informal economy, who are the most vulnerable and often constitute a majority. New policy measures could include extending social protection, for example through basic social security guarantees, in particular to workers in the informal sector, and by involving local government and non-state actors. The coverage of migrants from LDCs by social protection systems in host countries could provide valuable support.

Many LDCs have also adopted or developed support programs that provide loans, guarantees, or tax relief for firms that are temporarily affected so that workers continue to receive wage income or at least to ensure the firms still exist if the economies reopen. While some of these countries have been able to use domestic resources, many others rely on development partners for funding.

Provide external financial resources

The lack of domestic financial resources for economic stimulus is often a major constraint. Given the limited access to private capital markets, bilateral and multilateral funding will be essential. The IMF and multilateral development banks have already started to provide funding on a significant scale, but these efforts need to be scaled up to ensure that LDCs as the most vulnerable countries benefit.

As official development assistance (ODA) remains far more important for LDCs than for other groups (with an average ODA-to-GNI ratio of 5 per cent), the crisis response should include increasing ODA to rapidly meet existing commitments. Hence, bilateral development partners should also scale up their ODA in this crisis, rather than using budgetary constraints caused by Covid-19 as an argument to reduce their ODA.

The Covid-19 crisis also demonstrated the need for debt relief. LDCs will benefit from the suspension of bilateral loan repayments until the end of the year agreed to by the G20 countries, as well as the IMF’s cancellation of 24 LDCs’ debt payments for six months. However, these initiatives will certainly need to be expanded.

Restart economies smartly

There is a need to think about restarting economies in a smart way. In the absence of medical treatment or vaccines, or the capacity for “testing, tracing and isolation”, loosening social distancing provisions will facilitate the emergence of a second wave of infections. Hence, there is an urgent need for the international community to support vulnerable countries in developing and implementing strategies for restarting their economies that take the limitations on capacities and public health systems into account.

There is also a need for global coordination on loosening economic lockdowns. For example, tourism dependent economies have limited benefit from lifting restrictions on foreign arrivals if lockdowns in developed and advanced developing countries continue to depress external demand.

Restarting LDC economies should go beyond addressing emergency measures and include policies expanding productive capacities to address the root causes of limited economic resilience, lack of economic diversification and failure to create decent and productive jobs. Such policies should be based on strengthening national development governance that incentivizes the allocation of domestic and foreign resources (public and private) for industrial and technological upgrading while ensuring social and environmental protection. It should acknowledge possible impacts on global value chains from the Covid-19 crisis for the structural transformation of LDCs, for example by strengthening emphasis on regional approaches to overcome small domestic markets.

Transform societies for achieving the SDGs

The crisis has revealed again the vulnerability and inequalities inherent in current development models and the global economy. Hence, rebuilding economies will require placing the SDGs and the principles of human rights and gender equality at the center. A post-Covid-19 world must protect the gains made on gender equality and the empowerment of women and ensure that recovery is based on approaches that are gender-transformative, ecologically sustainable and leave no one behind. Building back smarter must mean that societies are healthy, clean, safe and more resilient, in particular for the most vulnerable.

The current crisis lays bare the reality that LDCs will not be able to become resilient without developing enhanced capacities in the health sector and beyond. Global cooperation is imperative in health, economics and elsewhere. Effective multilateral cooperation that benefits the most disadvantaged countries is a fundamental prerequisite for getting back on track toward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Follow Us