Development Issues No. 7: Global context for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: International trade

The Development Policy and Analysis Division at DESA, has prepared a series of policy notes to review current trends in important dimensions of the current global context with the intention of stirring debate about the urgent need to support an enabling international environment for SDG implementation. This note reviews recent trends in international trade and global trade patterns. It discusses the interlinkages between trade and sustainable development and concludes with a discussion that looks ahead on areas of improvement in global governance mechanisms to ensure that trade becomes an effective vehicle to achieve the SDGs.

A. Current trends in international trade

The global economy remains trapped in a prolonged episode of slow economic growth and slow productivity growth; both trends largely explained by weak productive investment. The slowdown in investment rates is, in turn, an additional constraint to trade, particularly in capital goods and productive inputs. In 2016, world trade almost came to a standstill, serving to propagate and reinforce the global slump in investment and restrain productivity growth.

This prolonged period of mediocre global economic performance is contributing to fuel growing discontent with the imbalanced distribution of burdens and gains from globalization and international trade, strengthening the appeal of protectionism and inward-looking policies in many countries. Should this trend in protectionism escalate, it will further impede international trade growth, undermine a recovery in investment, and prolong slow growth in the world economy. Unless these trends are reversed, progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) may be seriously compromised, particularly the goals of eradicating extreme poverty and creating decent work for all.

B. Recent trends of global trade pattern

Since the global financial crisis, international trade has not grown at the same rate as it did in previous decades. World trade volumes expanded by just 1.2 per cent in 2016, the third-lowest rate in the past three decades. The weakness in trade flows is wide-spread, which can be witnessed across developed, developing and transition economies. Furthermore, trade growth is not only weak from a historical perspective, but also in relation to overall economic growth. The ratio of world trade growth to world gross product growth has fallen steadily since the 1990s, from a factor of 2.5 to 1.[1]

The slowdown in global trade – on the one hand – is due to cyclical factors, such as weak aggregate demand and heightened uncertainty, but on the other hand, it is also due to structural shifts such as changes in the composition of global demand, the weakening of global value chains expansion and the slowdown in the pace of dismantling trade barriers between countries.[2] While some argue that the current trade stagnation is only temporary, others argue that it reflects fundamental changes in the global economy, and that world trade has already peaked.[3] In either case, it is projected that world trade growth is unlikely to outpace growth in world gross product significantly in at least the next several years, despite some expected modest recovery in global import penetration.[4]

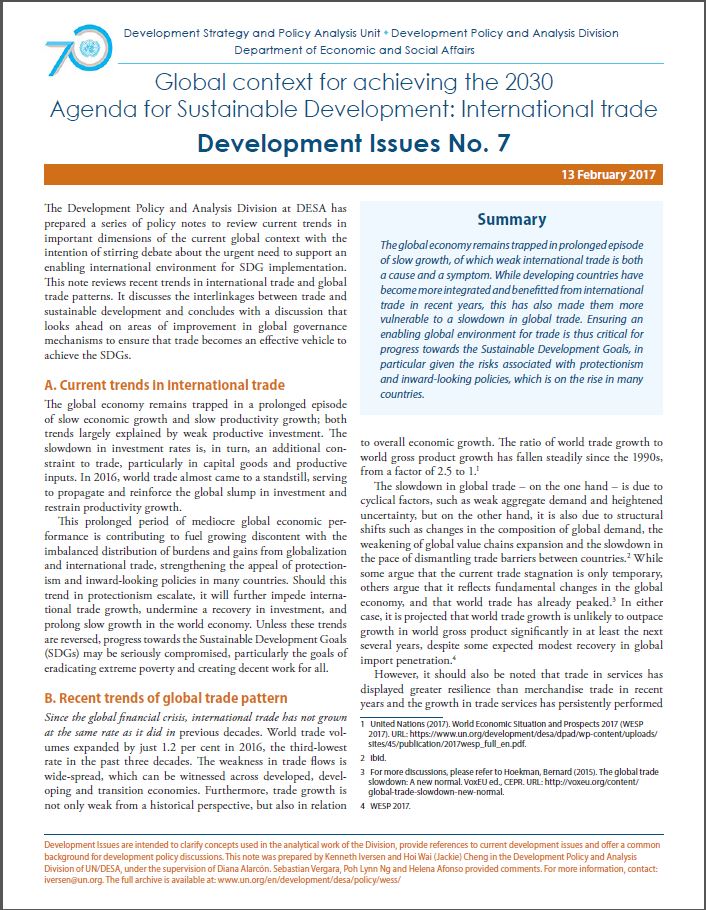

However, it should also be noted that trade in services has displayed greater resilience than merchandise trade in recent years and the growth in trade services has persistently performed better than merchandise trade since 2012.[5] The share of services in total trade is typically higher for developed economies, but it is also significant for large developing economies, such as Brazil (49 per cent), China (42 per cent) and India (58 per cent), after taking into account the value-added of services in the production of goods.[6]

Developing countries’ share of global merchandise export – in gross value terms – increased from 24 per cent in 1990 to 45 per cent in 2015. Similarly, the share of developing countries in global services export increased from 23 per cent in 2005 to 31 per cent in 2015 (figure 1). This relatively low level of participation of developing economies in global services market suggests there is still potential to further boost developing economies’ trade in services.

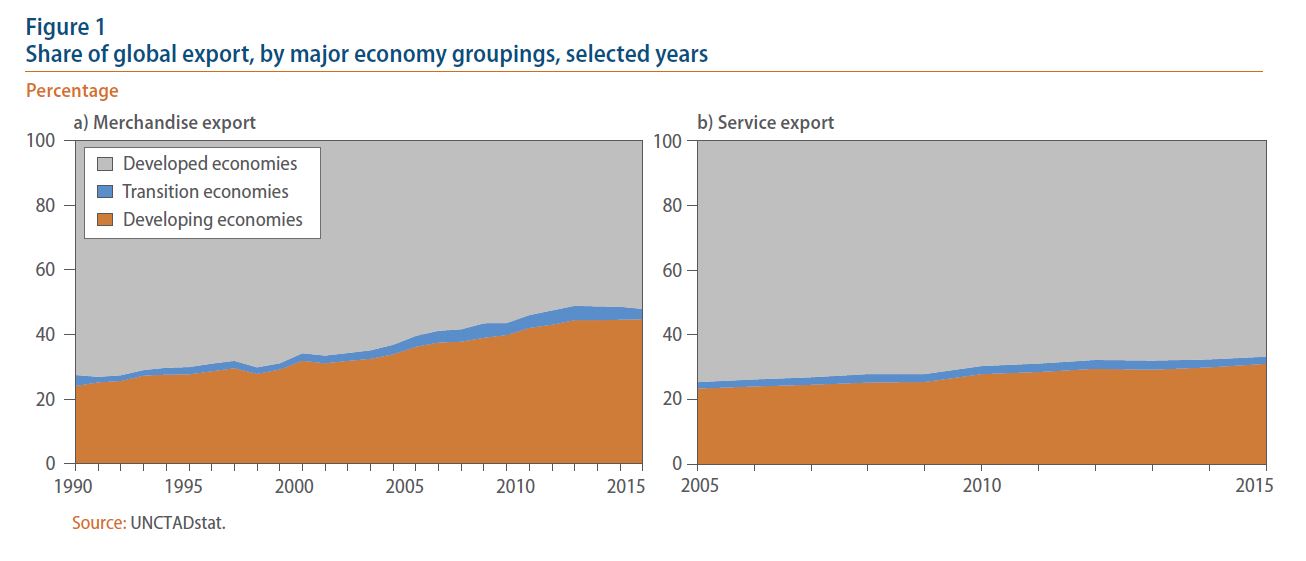

Remarkably, the share of south-south trade in total world exports doubled over the last 20 years, currently accounting for over 25 per cent of world trade. In the last couple of years, however, the rising trend of south-south trade has faltered (figure 2), reflecting the slowdown in economic growth in some large emerging economies.

Remarkably, the share of south-south trade in total world exports doubled over the last 20 years, currently accounting for over 25 per cent of world trade. In the last couple of years, however, the rising trend of south-south trade has faltered (figure 2), reflecting the slowdown in economic growth in some large emerging economies.

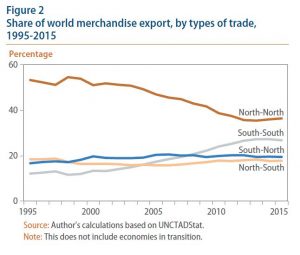

In terms of the regional pattern of trade, developed economies in Europe and North America are still playing a major role in international trade in both merchandise trade and services. However, one of the most notable developments since the year 2000 – and particularly after China’s WTO accession in 2001 – has been the rapid expansion of exports from East Asia to most other regions. There has also been an increase in merchandise trade within East Asia, partly due to an increased reliance on regional value chains (figure 3). At the same time, the share of intra-Europe and intra-North America trade in global merchandise trade is decreasing. Outside of East Asia, other developing regions also have witnessed increases in their shares’ in global trade, albeit to a lesser extent.

Trade trends in the least developed countries

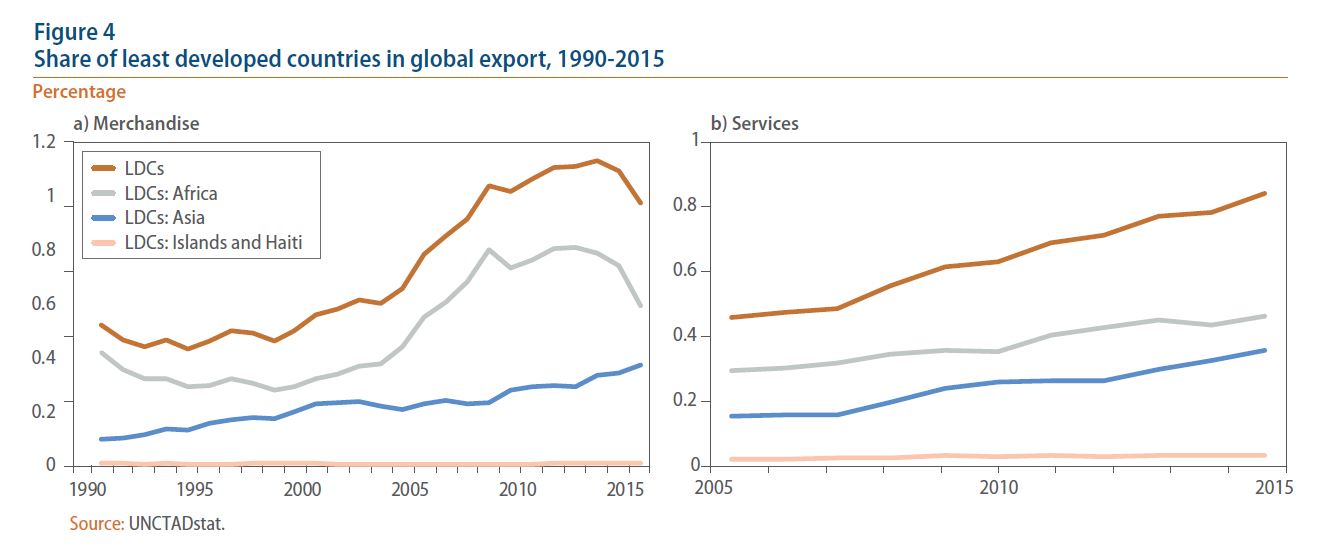

While LDCs represent around 12 per cent of the world’s population, the share in global merchandise export only increased from around 0.5 per cent of world export in 1990 to 1.1 per cent in 2013. In addition, since 2013, the export share of LDCs has dropped to 0.97 per cent in 2015, mainly as a result of a slow demand in China for primary commodities from LDCs in Africa. On the contrary, export of services from LDCs has almost doubled from 0.45 per cent in 2005 to 0.83 per cent in 2015, although from a very low base (figure 4).

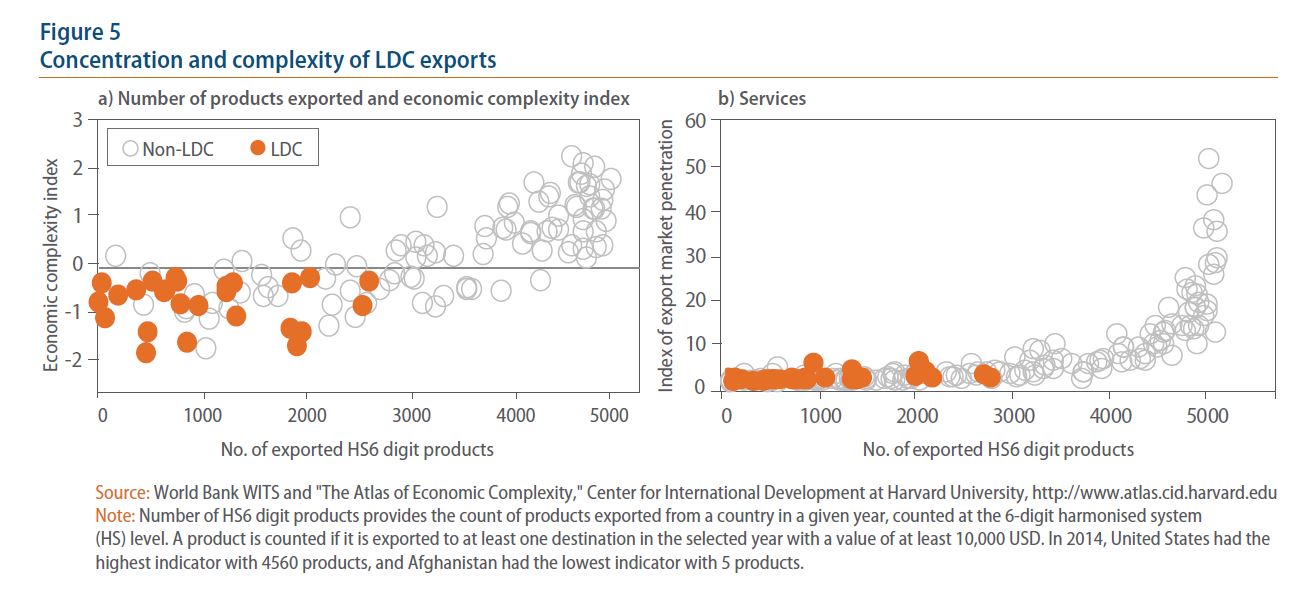

In addition, most LDC exports are concentrated in a few products of low complexity and directed to a few trading partners (figures 5a and 5b). These factors make LDCs particularly vulnerable to exogenous economic shocks, such as commodity price volatility and slow growth in their trading partners.

Note: Number of HS6 digit products provides the count of products exported from a country in a given year, counted at the 6-digit harmonised system (HS) level. A product is counted if it is exported to at least one destination in the selected year with a value of at least 10,000 USD. In 2014, United States had the highest indicator with 4560 products, and Afghanistan had the lowest indicator with 5 products.

C. Trade and development: Why trade is important for the 2030 Agenda

As globalization has created greater integration of production processes across countries, building a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system is critical for supporting growth and global development. Indeed, over the past decades, international trade has played an important role in supporting many countries’ economic growth and poverty reduction. In some cases, economies have also relied on export-led growth to expedite their structural transformation towards manufacturing production.

In the international cooperation agenda, trade has been among the main features in the last seven decades, with the aim of promoting economic integration of developing countries into the global economy through improved participation in international trade.

More recently, the 2030 Agenda has put significant emphasis on the role that trade can play in promoting sustainable development in developing countries, in particular in the LDCs. The trade-related targets reflect the different aspects of trade, including the promotion of a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system; the promotion of regional integration; the removal of trade distortions and improvement of market access; the diffusion of technology and trade-related capacity building; as well as the elimination of illegal extraction and trade with protected species.[9] Six of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) make direct reference to trade, such as trade distortions (2.b); the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (3.b); Aid for Trade (8.a); WTO agreements (10.a); fisheries (14.6); Doha round, exports from LDCs and duty free access (17.10, 17.11, 17.12).

While trade can be an effective tool in promoting sustainable development, higher level of trade alone does not necessarily translate into equitable development benefits for all, which is closely linked to SDG 10 of reduced inequalities. Economic theories and empirical evidences have shown that there are differentiated impacts of trade, both within and between economies, depending on economies’ factor endowment, the composition of exports, and the capacity of countries to facilitate structural change and the mobility of workers move out from shrinking sectors and into expanding sectors. In fact, there has been an increasing discontent around the world regarding the uneven impact of international trade within countries. Many have attributed the relative stagnant income growth of blue collar workers in developed countries over the past decades to trade, arguing that workers in low-end manufacturing industries in developed countries face direct competitions for jobs from those in developing countries and are not given sufficient assistance to pursue other employment opportunities.

Moreover, while international trade brings to an economy substantial and wide-spread benefits (e.g. lower prices, better and more variety of products and overall improved economic efficiency through better resource allocation), job losses that it entails are typically more concentrated in certain sectors/regions and are more noticeable than trade benefits. This – against the current backdrop of slow economic growth – leads to weaker overall public support for international trade and emerging calls for protectionism measures, even though available empirical evidence strongly suggest that stagnating wages of workers in developed countries are rooted in more complex causes, and only marginally related to international trade.

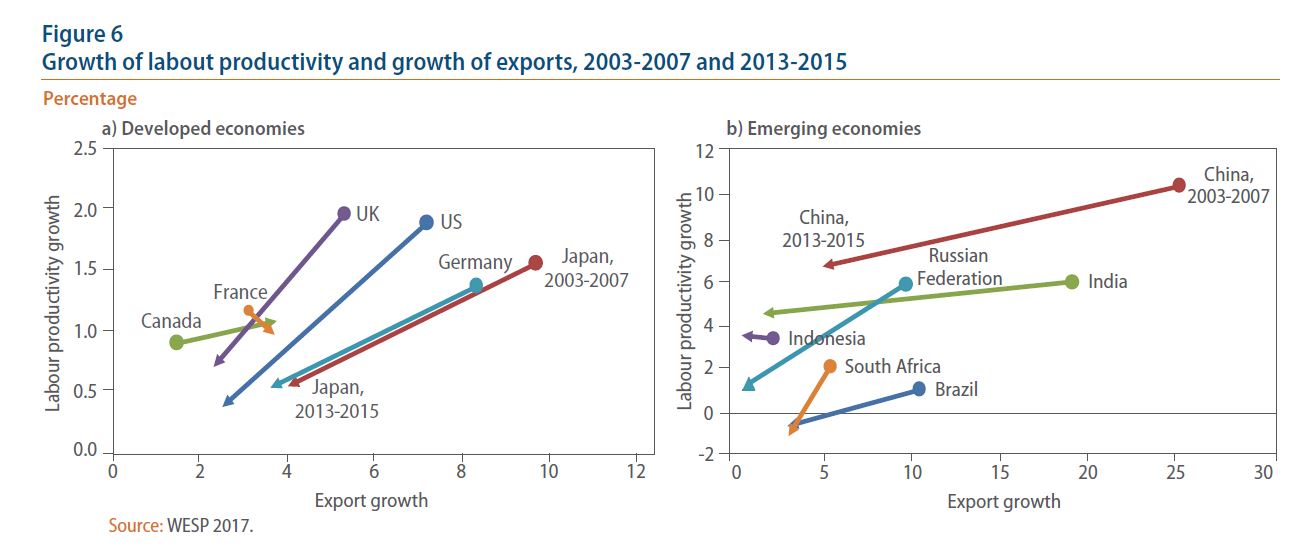

The rise in protectionism could further slow international trade, which would intensify the negative impact of the current subdued trade flows on labour productivity growth. In the past, exports have boosted productivity growth by creating economies of scale and introducing new production techniques. Comparing the years prior to the global financial crisis, with the years after, there is a clear trend towards lower labour productivity and export growth in most developed and emerging economies (figure 6). Another related factor is that the substantial weakening in fixed investment growth in both developed countries and emerging economies in the aftermath of the crisis appears to be highly correlated with the slowdown in global trade flows. Together, subdued trade and investment are affecting productivity growth, which can have long term implications for progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

D. Mixed results from the global partnership for development in the area of trade

International trade featured prominently in the Millennium Development Goals agenda under Goal 8; the global partnership for development. While significant progress has been made on the MDG 8 indicators related to tariffs,[10] overall progress to ensure a global enabling environment for international trade remains inadequate, with many developing economies still in a situation where they cannot reap the full benefits of international trade, mainly due to lack of progress in the international support required to facilitate diversification of production and higher value added of exports. Against this backdrop, the rising integration of developing countries into the global merchandise and services markets made them more vulnerable to external shock and the current stagnant global trade could be considerably damaging for economies that are highly dependent on commodities and single exporting sectors. As a result, further progress to ensure an enabling environment that promotes international trade and facilitates domestic structural transformation is critical for many developing countries in achieving the SDGs.

Looking forward, promoting trade and ensuring that it would be an effective vehicle in achieving the SDGs require concerted efforts in multiple areas, ranging from multilateral trade negotiations to domestic policies that complement trade policies. This section discusses recent developments in key trade-related areas.

- Progress has stalled in the multilateral trade negotiations under the Doha Round. While the WTO ministerial conference in Nairobi in 2015 delivered some progress through the Trade Facilitation Agreement that may contribute to reduce trade costs, there has not been much progress in other areas. Therefore there is an urgent need to make significant progress regarding the key role of a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system in promoting export diversification, trade and economic growth. Meaningful progress in the Doha Round is relevant to revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

- International trade continues to be largely free from tariffs both as a result of zero most favoured nation duties and because of duty-free preferential access. However, low average tariffs mask large differences across sectors and products. In particular, tariffs remain relatively high for labour intensive products that are important for developing countries, such as textiles, apparel and agricultural products. Tariffs on such products should be further reduced in order to support economic diversification in developing countries, especially the least developed countries.

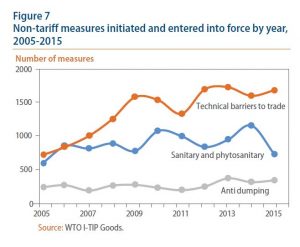

- International trade is also increasingly subject to and influenced by a wide range of policies and instruments beyond tariffs; non-tariff measures (NTMs) have become the key determinant for both market access and trade costs. The use of NTMs has increased since 2005, in particular the use of technical barriers to trade (figure 7). For LDCs, their agricultural sectors continue to be affected by both tariffs and NTMs in the global agricultural markets. NTMs pose a particular challenge for LDCs because such measures are more prevalently applied on their export products, and because the compliance with NTMs depends on technical know-how that many LDCs lack. Estimates show that fully liberalizing market access for LDCs to G-20 countries and eliminating the negative trade effect of NTMs on LDCs would increase their exports by about 15 per cent,[11] which could help to achieve the SDG target 17.11 of doubling the LDC share of global exports. However, eliminating NTMs is not straightforward as they often serve other developmental objectives. In this light, it is important to make NTMs work for sustainable development through policy coherence at both the national and international levels.[12]

- Many developed countries continue to provide significant support to their agricultural sector, which have negative implications for agriculture in the developing world. Even as subsidies to agricultural producers in OECD countries have declined marginally in recent years, they still amount to more than $211 billion in 2015.[13] SDG 2.b calls for the elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies to prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets. This would level the playing field in agriculture and benefit farmers in many developing and least developed countries.

- Insufficient productive capacity is still a key factor preventing many developing and least developed countries from increasing exports. This remains to be the case – and notably for LDCs – despite the fact that donors have steadily increased their commitments to build productive capacities in developing countries, for example through the Aid for Trade initiative. Further international efforts are needed to support supply capacity building in developing and least developed countries. Some areas of international cooperation include support to strengthen trade-related infrastructure, facilitate economic diversification and increase the value-added of exports. In this respect, the service sector could be particularly important in countries’ integration into global and regional value chains, through supporting productivity growth, reducing transaction costs, disseminating knowledge and facilitating resource allocation.

- While protectionism was relatively muted in the immediate years following the global financial crisis, there has been a more widespread appeal of protectionism and anti-globalization rhetoric in recent years, which may weigh further on global trade in the future. Countries should coordinate to resist protectionist pressures and ensure that the benefits of trade are spread more widely, both across and within countries. A failure to promote more inclusive trade and globalization could further embolden protectionist tendencies, which could prolong slow growth in the world economy and impede progress towards the SDGs.

- Domestic policies must complement trade policy to ensure benefits of international trade are more evenly distributed. Policy makers should put in place sufficient policies to smooth the transition of displaced workers back into the work force. These should include adequate safety nets, such as unemployment benefits, job-search incentives and re-employment services. Comprehensive retraining programmes should be in place to equip displaced workers with the skills to pursue employment opportunities in other sectors. Overall, there should also be a broader effort to create an adaptable work force with a high overall education level and the ability to engage in lifelong learning.

[1] United Nations (2017). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2017 (WESP 2017). URL: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/2017wesp_full_en.pdf.

[2] ibid.

[3] For more discussions, please refer to Hoekman, Bernard (2015). The global trade slowdown: A new normal. VoxEU ed., CEPR. URL: http://voxeu.org/content/global-trade-slowdown-new-normal.

[4] WESP 2017.

[5] For more discussions, please refer to the September 2016 edition of the WESP Monthly Briefing: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_mb/wesp_mb94.pdf

[6] OECD – WTO: Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database.

[7] The Economic complexity index ranks how diversified and complex a country’s export basket is. A higher numbers mean an economy is more complex. It measures the average ubiquity of the products the country exports and the average diversity of the countries that exports those products. For more details, see: "The Atlas of Economic Complexity," Center for International Development at Harvard University, http://www.atlas.cid.harvard.edu.

[8] The Index of export market penetration measures the extent to which a country’s exports reach already proven markets. It is calculated as the number of countries to which the reporter exports a particular product divided by the number of countries that report importing the product that year. For more details, see: World Bank Online Trade Outcomes Indicators - User’s Manual, available at: http://wits.worldbank.org/WITS/docs/TradeOutcomes-UserManual.pdf.

[9] For more discussions, please refer to Bellmann, Christophe and Alice V. Tipping (2015). The Role of Trade and Trade Policy in Advancing the 2030 Development Agenda. International Development Policy, 6.2. URL : http://poldev.revues.org/2149.

[10] Indicator 8.6: Proportion of total developed country imports (by value and excluding arms) from developing countries and from LDCs, admitted free of duty and indicator 8.7: Average tariffs imposed by developed countries on agricultural products and textiles and clothing from developing countries.

[11] UNCTAD (2016). Key Indicators and Trends in Trade Policy 2016.

[12] UNCTAD (2016). Trading into sustainable development: trade, market access, and the sustainable development goals. URL: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab2015d3_en.pdf.

[13] OECD: Producer and consumer support estimates database.

Follow Us