Climate change: Africa gets ready

Climate change: Africa gets ready

Ethiopian farmer Teshoma Abera laments the absence of rainfall and the failure of his crops.

Ethiopian farmer Teshoma Abera laments the absence of rainfall and the failure of his crops.It was not an easy life. But for fisherman Mohammadu Bello and his nine children the shallow waters of Lake Chad, a vast body of fresh water at the intersection of Niger, Chad, Nigeria and Cameroon, at least provided a living. Sales of lake catfish were brisk at the Doron Baga fish market, sustaining his family. But no more. Over the past 30 years the lake has steadily retreated from its former shores, leaving Mr. Bello and his neighbours high and dry and raising the prospect that the lake — once one of Africa’s largest — could vanish entirely. “Some 27 years ago when I started fishing on the lake,” he told the British Broadcasting Corporation in January, “we used to catch fish as large as a man.” Now, he said, the fish are small and what little is available is trucked into the market over the dry lakebed.

The causes of the lake’s shrinking, say scientists and researchers, include its increased use for irrigation and drinking. But more important, they say, are changes in the region’s climate, which have reduced the rainfall that once kept the lake and its feeder rivers full. These changes, which are occurring in every part of the world, are now widely understood to be caused by human activities, particularly those that use pollution-producing oil and other fossil fuels such as industrial processes, electricity generation and motor cars. Gases created by such activities are building up in the atmosphere, trapping too much of the sun’s heat and raising the earth’s temperature — a process known as global warming. As the earth heats up, it alters rainfall and other weather and climate patterns, threatening human, animal and plant life with potentially calamitous climate change.

The science is a bit abstract for fishermen like Mohammadu Bello, but the impact is not. “I don’t know what global warming is,” he said. “But what I do know is that this lake is dying and we are all dying with it.”

While some parts of Africa will get less rain, other areas will experience greater flooding.

While some parts of Africa will get less rain, other areas will experience greater flooding.In fact, Mr. Bello has found ways to cope. He and his family now till the rich soil left behind by the vanishing lake, growing vegetables for the Doron Baga market. He has acquired the skills and tools needed for his new profession as a farmer. But prospects for the 20 million people who depend on the lake and its rivers for water are less certain, and plans to divert water from other rivers into Lake Chad remain on the shelf for want of funding.

As the world prepares for the inescapable effects of global warming and seeks ways to reduce the emissions that cause it, Mr. Bello’s struggle to adapt will be shared by untold millions of people around the world. It is a challenge that looms particularly large in Africa.

Global warming, local impact

After a divisive and decades-long debate over the causes and potential impact of global warming, a series of studies by 2,500 scientists from 130 countries, part of the United Nations-sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has finally laid the issue to rest. In February 2007 the IPCC provided overwhelming scientific evidence that the use of fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas is releasing billions of tonnes of heat-trapping “greenhouse” gases into the atmosphere every year, causing air, ground and ocean temperatures around the world to rise at an alarming rate.

Countries can reduce harmful emissions and halt warming, noted IPCC Chairman Rajendra Pachauri in April, by investing in cleaner “green” technologies and changing consumer habits. But it is too late to prevent climate change from having sometimes severe impacts on the planet, and “it is the poorest of the poor in the world, and this includes poor people even in prosperous societies, who are going to be the worst hit.”

Demonstrators in Nairobi, Kenya, protest failure of developed countries to curb emissions of gases that contribute to global warming.

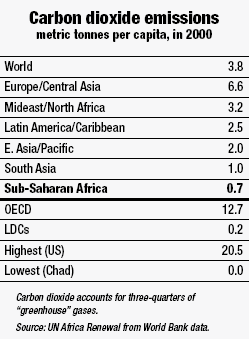

Demonstrators in Nairobi, Kenya, protest failure of developed countries to curb emissions of gases that contribute to global warming.Africa, the poorest and least developed of the world’s regions, will be especially hard-pressed to adjust. Although sub-Saharan Africa produces less than 4 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gases, scientists predict with “very high confidence” — as close as scientists get to saying they are certain — that the region’s diverse climates and ecological systems have already been altered by global warming and will undergo further damage in the years ahead.

Among the most worrying effects of global warming is the impact on water supply. Africa is fortunate to have large reserves of untapped water and some dry areas are likely to benefit from increased rain, but the Sahel and other arid and semi-arid regions are expected to become even drier. A third of Africa’s people already live in drought-prone regions and climate changes could put the lives and livelihoods of an additional 75–250 million people at risk by the end of the next decade. Flood-prone areas in Southern Africa, on the other hand, are likely to become wetter as rainfall patterns shift, causing floods to become more frequent and severe and diverting resources from development to emergency relief.

Farming, coastlines at risk

Africa’s agricultural sector is already hampered by its reliance on rain-fed irrigation, poor soils and antiquated technology and farming methods. It is likely to be hit hard as droughts and flooding worsen, temperatures and growing seasons change, and farmers and herders are forced off their land.

This could spell humanitarian and economic disaster on a continent where farming accounts for 70 per cent of employment and is often the engine for national economies — generating export earnings, industrial raw materials and inexpensive food. In some countries, scientists project, farmers will harvest just 50 per cent of current yields by 2020. The important fishing industry, as Mohammadu Bello’s situation reveals, is also likely to suffer as lakes and rivers dry up and rising water temperatures destroy commercial species of fish.

Coastlines and islands around the world are threatened by rising ocean levels as warming temperatures melt the earth’s polar icecaps. But East Africa’s low-lying islands and coastal regions are at particular risk of frequent flooding or becoming permanently submerged.

Higher water temperatures are expected to increase the power and frequency of hurricanes and other violent ocean storms. Africa’s coastal fisheries and the fragile ecosystems that support them could also be damaged if higher sea levels push salt water inland and destroy freshwater estuaries and coastal farmland.

‘Environmentally displaced’

As life becomes more difficult, the UN estimates, as many as 50 million “environmentally displaced” people around the world could join the exodus of migrants already crossing borders and oceans in search of new livelihoods. Many will move into overcrowded cities that today strain to provide jobs, housing and basic services, and will themselves be under threat from the effects of climate change.

Africa’s vast forests help absorb harmful gases in the atmosphere, and governments are working to slow excessive logging and other practices that contribute to deforestation.

Africa’s vast forests help absorb harmful gases in the atmosphere, and governments are working to slow excessive logging and other practices that contribute to deforestation.Climate change will also affect parasites like the tsetse fly and parasitic diseases such as malaria. Malaria is the single greatest killer of African children and imposes a $12 bn annual drain on African economies through death, medical costs and lost productivity. The mosquitoes that spread it thrive within a relatively narrow range of temperature and moisture, and some infected areas may become malaria free as they become drier. Yet simultaneously, regions currently outside the malaria zone may become infested as they get hotter and wetter. The World Health Organization has warned that globally, as many as 80 million more people could become infected as malaria spreads among populations lacking both natural protection against the disease and awareness of prevention and treatment methods.

Nor will Africa’s diverse plant and animal populations be spared. A study of nearly 5,200 plant species throughout the continent found that about 5,000 of them would lose much of their natural habitat to climate change. Of these, some 2,100 could lose all of their native habitat by 2085. Wildlife will fare no better. In South Africa’s famous Kruger game reserve, for example, studies show that two-thirds of animal species could disappear.

Adapting to climate change

African leaders, aware of the continent’s vulnerability, have long supported international efforts to combat global warming and climate change. African governments were prime movers behind the 1994 UN convention to combat desertification — a particular concern on a continent where two-thirds of the land is arid or semi-arid. Many African countries also were early signatories to the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the first and to date only international treaty setting binding limits on pollution emissions.

“Climate change is the greatest market failure the world has ever seen.”

— Sir Nicholas Stern, former World Bank chief economist

But because Africa’s small industrial base and limited transport system and power grid generates comparatively few greenhouse gases, reducing emissions has not been the region’s top priority. Instead African governments, civil society and their development partners are focused on planning for the coming climate shocks and assisting vulnerable communities to adapt. In September 2006, for example, the UNFCCC secretariat convened a workshop on climate-change adaptation attended by 33 African governments and a number of international agencies and civil society groups. The meeting highlighted the need for greater monitoring and early warning of climate changes and severe weather events like droughts and floods, and called for integration of long-term adaptation strategies into development and disaster-preparedness programmes.

Indeed, many aspects of Africa’s development agenda strengthen the ability of communities and countries to cope with climate change. Irrigation schemes, for example, are a vital component of efforts to improve food security and raise farm incomes in many parts of Africa. Only about 4 per cent of Africa’s farmland is irrigated. Bringing water to more acreage figures prominently in agricultural development plans. As seasonal rains become more erratic and less frequent due to climate change, irrigation also becomes an important adaptive strategy — helping farmers keep their livelihoods, increasing the food supply and allowing rural communities to remain on the land.

The problem, Sierra Leonean climate scientist Ogunlade Davidson told Africa Renewal from his Freetown office, is finance. “Climate change will have a major impact on agriculture in Africa,” he said. “Africa will have to change its agricultural systems. But if [Africa] doesn’t have enough money, it can’t,” since irrigation, fertilizers, improved technology and better seeds all require expensive investments. “Africa never enjoyed the financial benefits generated by putting greenhouse gases up there in the first place,” he continued, “so it never accumulated the wealth to be able to bear the shocks.” Because they now have to cope with the effects of a situation they did not create with resources they do not have, he noted, global warming is “a double loser for countries in Africa.”

‘Time for implementation’

Africa is receiving some assistance through two funds operated by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), a funding agency established in 1991 to assist developing countries finance environmental protection projects. The Least Developed Countries Fund is only for those countries classified as LDCs, while the Special Climate Change Fund supports adaptation, energy management, technology transfer and climate-related economic diversification projects in all developing countries. Since its launch in 2001 the LDC fund has attracted almost $116 mn in pledges, less than half of which has so far been received. Pledges to the special fund total $62 mn, over $52 mn of which has arrived.

Participating governments in consultation with the private sector and civil society develop National Adaptation Plans of Action (NAPAs) which identify vulnerabilities and needs and set country-specific priorities for action. Projects emerging out of the NAPA process are then eligible for funding. The GEF is administered by the UN Environment Programme, the World Bank and the UN Development Programme.

Ethiopia has now received $1 mn from the special fund towards a $3 mn programme to conduct pilot projects in the arid northern half of the country aimed at halting soil erosion. The project also seeks to strengthen the ability of pastoralists and farmers to cope with drought. Kenya has received $6.5 mn towards a $51 mn project to build national, provincial and community capacity to recognize and manage climate change and promote private sector involvement in climate-change adaptation.

The problem with the grants, says Mr. Davidson, a specialist in energy and the co-chair of the IPCC report on reducing global greenhouse gas emissions, is that they are too small to have a dramatic impact on threatened communities. Until very recently, he observed, international climate-change funding focused largely on scientific research into the causes and mitigation of global warming rather than on local adaptation programmes: “Take energy. If you upgrade to cleaner energy technology it will take considerable investment — more than a country would make otherwise. Who will pay that additional cost?”

The need to answer that question is one reason that a global commitment to combat climate change is important, Mr. Davidson said, “because it is the international community that can come up with the means. But if we put a long list of bureaucratic obstacles and conditionalities on it, those countries will not be in a position of accessing those funds and the problem will persist.” The time for studies and pilot projects is over, he asserted. “Now is the time for implementation.”

NEPAD’s plan: green growth

Whether those resources will be made available, however, is an open question. Africa has struggled for decades to find the capital needed for poverty reduction, and has fallen far short. Critics point out that despite Northern promises to boost development assistance to Africa and other developing regions to ease poverty and achieve the modest quality-of-life improvements set out in the Millennium Development Goals (see Africa Renewal, July 2005), aid actually decreased last year by over 5 per cent.

It is little wonder then, that the environmental action plan in Africa’s continental development blueprint, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), begins with the observation that “Africa is characterized by two interrelated features: rising poverty levels and deepening environmental degradation.”

The action plan, developed in 2003 with the assistance of the UN Environment Programme, notes that “throughout Africa, poverty remains the main cause and consequence of environmental degradation and resource depletion.… For African countries alleviating poverty is the overriding goal and priority of their development policies.… Without significant improvement in the living and livelihoods of the poor, environmental policies and programmes will achieve little success.”

The action plan emphasizes local, national and sub-regional responses to environmental degradation, improved environmental monitoring and research, and more effective international partnerships to promote “green” technology transfer, improve disaster preparedness and early warning systems and ease the consequences of climate change on the most vulnerable.

Because Africa contributes so little to planetary warming, the NEPAD programme on climate change stresses the region’s contribution to slowing the rise of global temperatures. Among the most important factors in the slowdown are its forests, which absorb and trap the carbon dioxide gas that is a principal contributor to warming. Africa contains 17 per cent of the earth’s remaining forestland and fully a quarter of its dense rain forests, which clean the atmosphere of emissions caused by polluters thousands of miles away. The forests also support an astonishing diversity of plant and animal life, an estimated 1.5 mn different species, which in turn provide sustenance for many millions of people.

Forests dwindling

But Africa’s forests are now vanishing at a rate of over 5 mn hectares per year, NEPAD reports, casualties of wasteful and unsustainable commercial logging and “slash and burn” clearing for agriculture. Almost two-thirds of all energy generated in Africa comes from firewood, particularly for household cooking and heating, which adds to the pressure on existing woodlands.

Although Africa and the international community have stepped up efforts to protect and restore forests in recent years, the results have been limited. Between 1980 and 1995, researchers note, some 66 mn hectares of forests have been destroyed. And despite initiatives like Kenya’s Green Belt movement, a grassroots women’s campaign that has planted 10 mn trees since 1977, the rate of deforestation is increasing.

NEPAD’s action plan argues that enacting and enforcing sustainable logging laws and reducing agricultural demand for forest land by improving yields on existing farms are critical aspects of any successful programme to protect Africa’s forests. But it is not easy. Logs are an important export commodity for some countries, and reducing exports could create budget shortfalls that may be difficult or impossible to fill. Boosting agricultural production and farm incomes is a NEPAD priority, but reforming Africa’s rural economy is a costly and long-term project and progress has been too slow to halt the addition of 1 million people each year to the ranks of the hungry.

In late May 2007, the NEPAD Secretariat announced that detailed climate-change responses for each of the continent’s subregions had been developed by a consortium of 800 African environmental, conservation and economic experts for consideration by African environment ministers. Those studies will form part of the presentation African heads of state will make at the next UNFCCC meeting in Bali at the end of the year.

Greening the market

The challenge of meshing urgent environmental needs with stubborn economic realities is particularly pressing in Africa, but it is scarcely unique to the continent. The expense of reducing greenhouse emissions has been a major obstacle to action against climate change over the past decade, even for rich countries. While scientists generally argue that it is cheaper to cut emissions now and prevent the worst effects of climate change, some governments argue for slower and smaller reductions, pointing to the cost to industry and consumers and the risk of damaging the global economy.

In a major study of the economics of climate change for the UK in 2006, Sir Nicholas Stern, a former chief economist for the World Bank, argued that the nature of free markets prevent them from being naturally greener. It works like this: The financial benefit of manufacturing a tonne of steel is enjoyed by a small number of people — the mill owners, workers and shareholders. But the cost, when measured in greenhouse emissions and environmental damage, is distributed over billions of people around the world over many generations. This provides little incentive to the mill owners to raise their production costs to reduce pollution. “Climate change,” noted Dr. Stern “is the greatest market failure the world has ever seen.”

Changing the economic processes by raising the cost of pollution is therefore important if global efforts to halt global warming are to succeed. One proposal is to tax greenhouse gas emissions, thereby making it cheaper to prevent them than to generate them. But “carbon taxes” have encountered strong opposition in many countries and have been adopted by only a handful of governments.

A different way to put a price on pollution, called “cap and trade” schemes, has proven more popular since the Kyoto Protocol came into effect. Kyoto requires industrial country signatories to reduce greenhouse gases by about 5 per cent from 1990 levels. The agreement also established the UNFCCC’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which allows heavily polluting industries to, in effect, buy pollution rights from a country with low emissions by investing in green projects there.

If, for example, the theoretical steel mill owners are required by their Kyoto-compliant government to reduce their carbon emissions by 10 tonnes, they can invest in improved anti-pollution and manufacturing technology to meet that target. But the mill owners may find it cheaper to plant enough trees in Africa to absorb 10 tonnes of carbon pollution instead. Under the CDM, the mill owners are permitted to count the carbon trapped in the new trees against their reduction target, saving them money and creating incentives to invest in the continent.

The same rules would apply to a project to replace a polluting coal-fired power plant in Africa with one producing cleaner hydro or natural gas power, allowing Northern investors to count the reduction in power plant emissions in Africa against their domestic reduction requirements. The agreement even allows CDM “carbon credits” to be bought and sold in much the same way that corporate stocks are traded.

Since it was first suggested at the end of 1997, carbon trading has developed into a $22 bn industry. Africa hoped to capitalize on its low emissions to attract CDM investments and help finance green development. But to date Africa has attracted less than 2 per cent of CDM projects worldwide, owing to the absence of sophisticated financial and marketing institutions and limited administrative and management capacity.

The programme has proven controversial for other reasons as well, with critics arguing that wealthy countries and businesses use the mechanism to avoid reducing their emissions and cheat on their Kyoto obligations by inflating the environmental value of their offsetting projects.

But with the Kyoto agreement set to expire in 2012 and evidence mounting that the earth is heating faster than expected, Africa’s green development agenda may yet benefit from efforts to change the economics of global warming. “We have a very short window for turning around the trend we have in rising greenhouse gas emissions,” the IPCC’s Rajendra Pachauri told reporters in Bangkok in May. “We don’t have the luxury of time.”

Security Council: climate change may threaten peace

The economic, political and social consequences of climate change could threaten world peace unless the world acts to prevent it, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon told the Security Council on 17 April. “Throughout human history people have fought over natural resources,” he noted. “Changing weather patterns, such as floods and droughts and related economic costs … could risk polarizing society and marginalizing communities,” thereby increasing the risk of conflict and violence.

The unusual day-long session, an initiative of the UK, marked the first time the Council addressed climate change. Its presence on the agenda was not without critics. Pakistan’s Ambassador Farukh Amil, speaking on behalf of the influential G-77 and China group of developing countries, argued that the topic was outside the Security Council’s mandate and an encroachment on the authority of larger and more representative bodies, including the General Assembly and the UN Economic and Social Council. But the session was welcomed by other speakers, including those from small island states facing the prospect of inundation from rising sea levels.

The meeting was chaired by UK Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett, who said, “Today is about the world recognizing that there is a security imperative, as well as economic, developmental and environmental ones, to tackling climate change.” Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, she noted, has already described climate change as “an act of aggression” by the polluting industrial North against the developing South — a comment that underscored the link between the environment and world peace. “He is one of the first leaders to see this problem in security terms,” she asserted. “He will not be the last.”