Court must fight impunity, say African delegates

Court must fight impunity, say African delegates

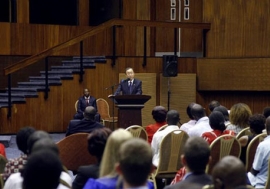

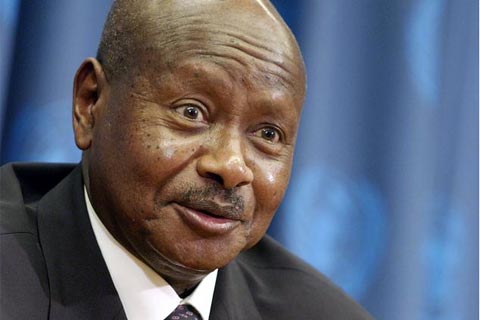

Africans are the main beneficiaries of the International Criminal Court, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni said at the opening of ICC review conference in Kampala.

Africans are the main beneficiaries of the International Criminal Court, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni said at the opening of ICC review conference in Kampala.When African delegates arrived in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, in May for the first review conference of the statue that established the International Criminal Court (ICC), they were aware that some in Africa believe that the court unfairly targets political figures from the continent. Indeed, all five cases currently being handled by the court, which is based in The Hague, involve African leaders. It was therefore notable that delegates from 30 African countries ultimately agreed that the charge of “unfairness” is flawed. The African delegates came out of the 12-day conference as the strongest defenders of the court.

“Africa has the majority of member states to the ICC,” noted Sierra Leone Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Vandi Chidi, who led the African group during the first week of the conference. “You can’t say that the court is targeting African leaders. They are the ones who referred the most cases. The notion can only be said by African states that are not part of the Rome Statute,” which set up the court.

At the opening, the host, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, described the conference as an opportunity to counter the claim that the ICC is a court for Westerners to judge Africans. He urged Africans in general to embrace it, since they are the beneficiaries.

Warrant against Sudanese president

On 4 March 2009, judges at the ICC issued an arrest warrant against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, in connection with the conflict in Darfur. Shortly after, the African Union (AU) called on the UN Security Council to suspend the ruling, saying its execution would lead to more violence in Darfur and destroy the prospects of a peaceful solution. Since then, President Bashir has traveled to several countries across the continent.

But a few hours before the conference began, President Museveni told ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo that the Sudanese president had not been invited for the AU summit set for Kampala at the end of July. The government in Khartoum issued a strongly-worded protest, prompting some Ugandan officials to qualify Mr. Museveni’s comments.

In June, President Bashir was invited by South Africa, alongside 20 other African presidents, to attend the opening ceremony of the World Cup. But the Sudanese president failed to attend. Earlier, in response to a question in parliament, South Africa President Jacob Zuma hinted that his country had a responsibility, as dictated by international law, to arrest him should he come.

Referring to the AU position in 2009, a delegate from Malawi, who preferred anonymity because his president is the current AU chair, commented: “What African presidents said and decided last year does not matter. Their action [now] is speaking out loud and clear. Bashir is isolated and they will continue to quietly isolate him.”

‘They all must answer’

According to Zambian delegate Liboma Inyambo, “People have realized that they must fight impunity and the court is helping Africa do just that. Everybody agrees and this is going to be one of the top agendas at the upcoming AU summit.” African delegates argued that the indictment of President Bashir should not be drummed above other cases being pursued by the court. “They all must be pushed to the corner. African leaders or rebel leaders, they all must answer,” said Mr. Inyambo.

“Good African leaders have nothing to fear from the ICC,” said Nobel Prize winner Wangari Maathai, from Kenya. “Impunity still rules across Africa. We should not be protectors of those who have committed atrocities.”

Mr. Ocampo added: “We believe that the court is working for Africa, not against Africa.” He called for both public and diplomatic support in the execution of arrest warrants issued by the court.

Victims’ worries

From a different perspective, many of the war victims who attended the conference expressed disappointment at the pace with which the ICC is operating. They feel that the cases are taking too long to conclude and governments are not playing their part in arresting those indicted.

It has been five years since the indictment of rebel leader Kony and other commanders of the Ugandan Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), noted Grace Arach, a Ugandan victim. “If he is arrested and taken to the ICC, how long will it take to prosecute him?” she asked. Ms. Arach, now 26, vividly remembers the day the LRA rebels ambushed her family, burned the vehicle in which they were traveling, killed her father and abducted her. She escaped in 2001, after eight years in captivity. She has now graduated with a diploma in counseling.

Gilbert Basigi, a war crime victim from the Ituri region in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, questions the powers of the ICC. “Those who committed atrocities are freely moving, eating in Congo hotels, while we are suffering. Why can’t government arrest them?”

The ICC review conference concluded with many having taken the floor to reiterate their commitment to its mission of fighting against impunity, bringing justice to victims and deterring future atrocities.

— Africa Renewal online