Empowering women to fight AIDS

Empowering women to fight AIDS

HIV-positive mother and child in Tanzania: Low economic and social status, along with other factors, leave women more vulnerable than men to infection.

HIV-positive mother and child in Tanzania: Low economic and social status, along with other factors, leave women more vulnerable than men to infection.Out of nearly 25 million Africans today living with HIV/AIDS, almost 60 per cent are women, reports the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). In some African countries, more than two-thirds of people with the virus are women.

It was therefore appropriate that UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed an African woman, Ms. Elizabeth Mataka, as his new special envoy for AIDS in Africa. A citizen of Botswana, Ms. Mataka has lived and worked in neighbouring Zambia for many years, and since 1990 has been on the frontline of Africa’s struggle against the disease, as a community activist, programme director and international advocate. At the time of her UN appointment on 21 May, she was serving as executive director of the Zambia National AIDS Network and as vice-chairperson of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

The struggle against HIV/AIDS requires a far greater focus on women, says Ms. Mataka. “Unless we empower women not just economically, but with technology that they can initiate and control to protect themselves against infection, we will remain with very limited success,” she told Africa Renewal from her office in Lusaka.

The reasons for women’s particular vulnerability to HIV, which is transmitted by sexual intercourse and exposure to infected blood, are complex and varied. Sexual assault and other forms of violence against women is one important factor (see Africa Renewal, July 2007). Biology can also make women more susceptible to infection.

But the factors that leave women most at risk, says Ms. Mataka, and the ones that must be tackled if the epidemic is to be defeated, are economic, social and political. “Look at the economic position of women,” she says. “Most women find themselves totally dependent on their male partner. That tends to limit their negotiating power in terms of safer sex.

‘Connect the dots’

The consequences of gender inequality are not limited to Africa. UNAIDS reports that nearly half of the 37 million adults living with HIV/AIDS globally are women — and that their numbers increased by more than 1 million between 2004 and 2006. The UN helped launch the Global Coalition on Women and AIDS in February 2004 to raise awareness of the mounting crisis among women and to develop prevention and treatment programmes tailored to their needs (see Africa Renewal, October 2004).

In July 2007 the World Young Women’s Christian Association organized a women’s conference on AIDS in Nairobi, Kenya. It drew more than 1,800 people from throughout the world and focused on expanding women’s leadership in anti-AIDS initiatives. The conference’s call to action declared that women had a human right to equal access to HIV/AIDS services and demanded an end to economic and social discrimination (see box).

Dr. Peter Piot, the head of UNAIDS, told delegates that “this is the time to connect the dots between AIDS and gender equality.” He declared that the “feminization” of AIDS is the most significant development in the evolution of the global epidemic. “The first question we need to ask for every AIDS activity is, of course: ‘Does it pass the test for women?’ There is no such thing as a gender-neutral programme.”

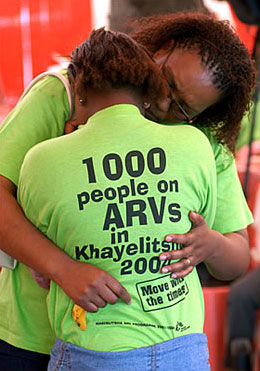

A rape victim being comforted at a ceremony in Khayelitsha, South Africa, the site of an experimental programme to treat people with anti-retroviral drugs.

A rape victim being comforted at a ceremony in Khayelitsha, South Africa, the site of an experimental programme to treat people with anti-retroviral drugs.Success starts with solidarity

Focusing on Africa specifically, Ms. Mataka notes that “in some of the cultures we have here, women are taught from the cradle to be subservient and obedient.” Such an upbringing, combined with economic dependence, she says, makes it very difficult for women to protect themselves from infection, or to get tested and treated. “How many women, if they went for testing, would go home and announce their status if they are positive and hope to remain in that home? And if they are thrown out of the house, what options do they have? Where do they go?

Even women who have decided to end a dangerous or abusive relationship can find themselves isolated and trapped. “Women are under real pressure to remain in a marriage,” Ms. Mataka explains. “Mostly, society will not support a woman in her decision to divorce if she thinks that marriage is risky. People just say: ‘That’s how it is. That’s how men are.’ They need support to get away from risky situations.”

Yet changing the economic and social factors that put women at risk is “a huge job,” she admits. The starting point, she adds, “would be for us to build very strong solidarity movements to support each other…. Before you can do anything else you must have somewhere to sleep, something to eat. You must feel comforted by other women, supported by them. Women must come together irrespective of status, education and wealth.”

Many early anti-AIDS programmes for women, she argues, failed to focus specifically on women’s real needs and lacked concrete targets. Simply “mainstreaming” gender into AIDS programmes did not work. It is vital to set numerical targets and specific timeframes. She cites the successful effort to increase by eight times the number of Africans on lifesaving anti-AIDS drugs in just three years. “We must have the same thing with women’s empowerment,” she asserts. “We must have definite programmes so that women are supported.”

Progress amid setbacks

For both men and women, the battle against AIDS remains daunting. Despite a thirtyfold increase in funding for global anti-AIDS programmes since 1996, the number of new infections and deaths continues to rise. Spending on HIV/AIDS prevention, care and treatment is expected to reach $10 bn in 2007, but that is less than half the amount needed.

Access to lifesaving anti-retroviral drugs has soared since 2003. They now reach 2 million people in developing countries, including over 1 million in Africa. Yet that is less than a quarter of those who need the medicines, and the rate of new infections is six times the number of new patients entering treatment annually. “This is not acceptable and it is not sustainable,” Dr. Piot cautions, noting that such trends could doom efforts to reach the UN target of universal treatment access by 2010.

As grim as such numbers may seem, they are worse for women. Just 11 per cent of pregnant women receive treatment to prevent passing the virus to their newborns, and in some of the worst-affected African countries, just one in 10 women has access to HIV testing.

But to Ms. Mataka, there are signs of progress. “The fatalism that I sensed maybe five or six years ago is certainly on the decline,” she says. “People think the response is in their hands and they can do something about it.”

The availability of treatment, in particular, has begun to fundamentally change public attitudes, she notes. “People know that if they are ready for treatment, there will be treatment. Increasingly, people are no longer seeing the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS positivity as a death sentence. People are going back to work. Children are growing up with their parents.”

There are other modest signs of progress. Although infection rates are static or increasing in most African countries, the rate of increase has begun to slow among 15- 24-year-olds in eight East African countries. UNAIDS reports that young people in Kenya and Malawi are having fewer sexual partners, a sign that years of HIV prevention programmes are beginning to have an impact on personal behaviour.

Ms. Mataka also cites advances in technologies that women can control, such as microbicides and female condoms, and wider use of male circumcision, which appears to reduce infection rates among men. She cautions, however: “We can’t lead people to believe that it [technology] is a panacea to everything. People still have to practice other safer sex strategies like minimum sexual partners and condoms.”

African solutions

Despite the challenges, special envoy Mataka is optimistic about the future. “There is new hope in Africa.” More needs to be done to recognize “the positive developments that Africa is making, that communities are making…. People are mounting prevention and treatment programmes in the workplace, addressing issues of stigma and defending the rights of people living with HIVAIDS.”

At the end of the day, she asserts, “there must be an African solution to this problem…. This is not to say that Africa does not need international resources. Africa needs massive international support.” African ownership and political will in the fight against AIDS is indispensable, “but until that political will translates into resources, it will have a questionable impact on the epidemic.”

Africa itself must do more. “It’s a critical emergency,” she concludes, and women are the key. “We need to build capacity and women’s leadership so that they take control of programmes that are designed for the needs of women. Africa needs to realize that without dealing with the issue of women, there will be no progress in turning HIV/AIDS around.”

Women’s call to action

Declaring that “women’s leadership is essential” in the fight against HIV/AIDS, over 1,800 delegates to the World YWCA International Women’s Summit adopted a global Call to Action in Nairobi, Kenya, on 7 July.* The manifesto called on women to advocate with their governments and civil society organizations to:

- Strengthen HIV/AIDS education and awareness programmes for women and girls

- Involve women living with HIV/AIDS in decision-making

- Combat stigma and stereotypes, including among women and girls

- Promote gender equality and women’s human and reproductive rights

- Expand efforts to end violence against women

- Provide women and girls equal access to education and economic opportunities

- Ensure women’s access to HIV/AIDS care and treatment services

- Revise anti-AIDS programmes to make them responsive to women

- Invest in leadership development for women and girls

- Guarantee the full participation of women at all levels of society.