Setting foreign fighters on the road home

A fighter from the Rwandan FDLR rebel group in the eastern Congo: Pondering the prospects for a return back home?

A fighter from the Rwandan FDLR rebel group in the eastern Congo: Pondering the prospects for a return back home?Initially in late January, small clusters of haggard Rwandan rebels and refugees started to trickle out of the forests of the Congolese province of North Kivu. Within just a couple of weeks their numbers climbed into the hundreds. By June, more than 8,000 — including about 1,000 former combatants — had been repatriated back to neighbouring Rwanda by United Nations peacekeepers and refugee workers.

Antoine Uwumukiza, who fled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) some 15 years ago in the aftermath of the 1994 Rwanda genocide, was one of those who joined the exodus back home. “The international community has set plans to help us surrender, so we decided to go back to Rwanda,” he told a reporter for the Washington Post. “We’ve heard people say, ‘In Rwanda, there is good government,’ and we have decided to go see if it’s propaganda.”

Over the past decade, hundreds of thousands of other Rwandans had already gone back, discovering that the government’s policy of national reconciliation is not just propaganda. Refugees and even soldiers from the Hutu ethnic group found they had a place alongside the genocide survivors, who are mainly Tutsi (see box).

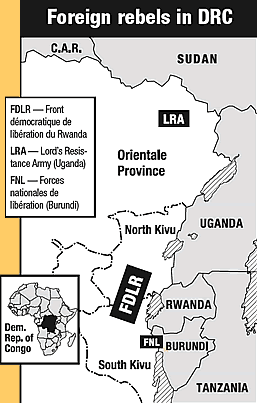

But several thousand combatants of the Hutu opposition group Front démocratique de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) still remained in the eastern Congolese provinces of North and South Kivu. Bands of fighters from the notorious Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) of Uganda were also active in the Congo’s far northeast.

Both groups have terrorized Congolese villagers, killing thousands, kidnapping hundreds and engaging in widespread sexual brutalities. The insecurity has led local residents, especially women, to demand greater protection (see box). The rebel commanders have also used extreme tactics to prevent refugees — and their own fighters — from trying to return home.

Alan Doss, UN special representative for the DRC, visiting a camp for displaced people in the eastern Congo: Once foreign combatants have been repatriated and security is restored, the “real battle” for economic and social development can begin.

Alan Doss, UN special representative for the DRC, visiting a camp for displaced people in the eastern Congo: Once foreign combatants have been repatriated and security is restored, the “real battle” for economic and social development can begin.That situation festered until the Congolese government invited several thousand troops from Uganda and Rwanda into the DRC in December 2008 and the first months of 2009 for joint operations against both sets of rebels. The military pressure momentarily dispersed the rebel leadership.

“At that point, we decided to make the most of the situation,” explains Bruno Donat, then head of disarmament and demobilization for the UN Mission in the DRC (MONUC). He and his colleagues took “extraordinary measures” to convince FDLR combatants to hand in their arms and return to Rwanda voluntarily, he told Africa Renewal. By deploying additional mobile teams, opening a 24-hour call centre, dropping leaflets by helicopter and broadcasting from mobile radios, they were able to tell rank-and-file FDLR fighters how to safely reach UN repatriation assembly points.

‘Significant threats’

While the circumstances in the Congo have been especially dramatic, they are not unique in Africa. Several thousand kilometres across the continent — and at the same time that the military operations were under way in the eastern DRC — Liberian combatants who fought in Côte d’Ivoire’s civil war were threatening to disrupt that country’s peace process if they were not given larger demobilization payments.

The people of the Central African Republic (CAR), just north of the DRC, still remember the massacres and other atrocities carried out in 2002–03 by Congolese and Chadian fighters, brought into the country by rival political factions. Today armed groups from Chad and Sudan continue to pass through the CAR, posing further risks to a fragile national dialogue intended to resolve that country’s conflict.

Foreign fighters and armed groups that operate across borders “are significant threats to regional security in all areas where they exist in significant numbers,” notes the study “Combatants on Foreign Soil,” prepared by the UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa (OSAA).

Unlike combatants who are nationals of a country emerging from war, most foreign fighters cannot simply rejoin local communities after they have handed in their weapons and left their armies. Frequently there are no organized repatriation programmes. Where they do exist, as for Rwandans, fear, suspicion and poor relations between governments may mean such fighters are left behind, as persistent security threats.

Complicated entanglements

Foreign combatants are not new in Africa, notes the OSAA study, which was presented to an international conference on disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) in Africa, held in the Congolese capital, Kinshasa, in June 2007 (see Africa Renewal, October 2007).

African insurgent forces have long operated across poorly guarded national borders. Some have been viewed positively, especially in the early anti-colonial liberation struggles or the movement against the apartheid regime in South Africa.

While such insurgent groups often had clear political goals and disciplined fighting forces and sought some popular support from local communities, that has been rare in the many civil wars that have swept Africa over the past two decades. Not only have government and rebel forces both targeted civilian populations, but they have also tried to get support — including combatants — from abroad. The entanglement in these civil wars of fighters from neighbouring countries has added a further layer of complexity and violence.

West African ‘regional warriors’

West Africa was one region where multiple armed groups operated repeatedly across national borders. In 1989 rebel forces entered Liberia from neighbouring Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire. Then from Liberia, Charles Taylor, initially as a warlord and later as president, backed the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in its attacks against the government of Sierra Leone. At various times combatants from Liberia, Burkina Faso and other countries fought directly alongside the RUF. Later, two new rebel groups opposed to President Taylor launched a second civil war in Liberia, initially striking from Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire and eventually prompting Mr. Taylor’s departure in 2003.

Following peace accords in Sierra Leone and Liberia, UN-organized DDR programmes succeeded in demobilizing tens of thousands of fighters from the various domestic factions (see Africa Renewal, October 2005). But there was little systematic effort to help foreign combatants return home. “The scourge of foreign ex-combatants remains a largely ignored tragedy,” then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan observed in a 2005 report on cross-border problems in West Africa.

A UN helicopter drops leaflets in an area of the Congo where FDLR fighters are active, with information on how to arrange their repatriation to Rwanda.

A UN helicopter drops leaflets in an area of the Congo where FDLR fighters are active, with information on how to arrange their repatriation to Rwanda.This difficulty was compounded by shortcomings in fully reintegrating ex-combatants back into civilian life. Many youths were left dissatisfied and marginalized, with no jobs, little education and few skills other than handling weapons. So when war erupted in Côte d’Ivoire in 2002 and both sides in that conflict sought new foot soldiers, there were thousands of ready recruits willing to cross the border. While they included a few from Sierra Leone, most came from Liberia: an estimated 2,000 or so fought with the pro-government forces and another 1,000 joined the rebels occupying Côte d’Ivoire’s north and west.

The US-based Human Rights Watch, in a 2005 report on West Africa’s “regional warriors,” interviewed some 60 combatants from 15 groups. Most had fought in at least two conflicts in the region. “There are some of us who can’t seem to live without a weapon — anywhere we hear about fighting we have to go,” said a 24-year-old Liberian who had fought in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire.

For these fighters the main motivation appears to have been economic. Most of those recruited for successive wars lacked jobs and lived in desperate economic conditions. The recruiters and commanders promised they could loot. Some readily shifted allegiances from one group to another as the opportunities for pillage changed.

To reduce the likelihood of such an “insurgent diaspora,” experts argue, regional organizations need to dissuade governments from recruiting or backing foreign fighters, while peacekeeping forces should better coordinate their own efforts. The UN Office for West Africa has promoted more exchanges among peacekeepers in the region to align their reintegration programmes. And, gaining from the experience of past shortcomings, the UN mission in Côte d’Ivoire now works closely with its counterpart in Liberia to facilitate the repatriation of foreign ex-combatants.

It is just as important, experts argue, to better reintegrate former fighters into their own societies. If they have jobs, social connections and other opportunities at home, they will be less open to recruitment for wars abroad (see Africa Renewal, April 2009). Human Rights Watch noted that most Liberian interviewees who were approached to fight in Côte d’Ivoire or Guinea refused to go, since they were enrolled for job training or education programmes in Liberia.

Great Lakes: overcoming enmity

In Africa’s Great Lakes region, domestic political conflicts combined with serious disputes among neighbouring governments to create an especially volatile environment for cross-border military action. In the 1990s Burundi, Rwanda and Congo were all swept by national conflicts, while the insurgency led by the LRA continued to inflame northern Uganda and became entangled with the conflict in southern Sudan.

After predominantly Tutsi insurgents took power in Rwanda in 1994, many people who had taken part in the genocide, as well as soldiers of the defeated government and hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees, fled to the eastern provinces of Zaire (as the DRC was then called). Supported by the Zairean dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, the Hutu fighters struck back at the new Rwandan government. In 1996 Rwanda and Uganda retaliated by supporting dissident Congolese forces, which succeeded the following year in deposing Mobutu.

But then a new Congolese civil war erupted in 1998, eventually spawning numerous armed factions and drawing in troops from a half dozen neighbouring countries. Meanwhile, civil war raged in Burundi, and rebel groups took advantage of the chaos in the DRC to use its territory for staging attacks.

To maximize their leverage, African governments must better analyze emerging-market trends and develop a strategic focus, argues the UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa.

While fighting was under way, there were few options for reducing the involvement of foreign combatants. But as the wars came to an end, foreign government support declined and some groups either returned home or lost strength.

The DRC peace agreement signed in 2002 provided for the withdrawal of foreign armies and the formation of a transitional coalition government of the main Congolese contenders. But some dissident groups remained active in the eastern DRC, at times with tacit support from neighbouring countries.

In 2006, area governments held an International Conference on the Great Lakes Region to try to ease the animosities. They pledged to stop supporting armed groups in neighbouring countries and allowing foreign insurgents to operate from their own territories. In that spirit, the Rwandan government decided in January 2009 to arrest Laurent Nkunda, head of a Congolese dissident faction that had previously enjoyed some support from Rwanda. “His intransigence had turned him into an obstacle to peace,” Rwandan President Paul Kagame explained. Following General Nkunda’s arrest, his group reached a peace agreement with the Congolese government.

Meanwhile, in Burundi, a peace accord in 2003 led the largest rebel group to demobilize and join the political process. But a hard-line group, the Forces nationales de libération (FNL), remained in opposition, operating mostly from within Burundi, but with a few hundred fighters in the DRC as well. Eventually, in April 2009, the FNL also agreed to disarm, merge some of its forces into the Burundian army and transform itself into a political party. From a Congolese perspective, another foreign group was on its way home.

Between persuasion and force

Although both Uganda and Rwanda have also sought to persuade their opponents to demobilize and repatriate, the response has been mixed. In response to an amnesty offer by the Ugandan government, some 15,000 LRA fighters, mainly in northern Uganda and southern Sudan, renounced violence and disarmed. Most of the remaining LRA forces today operate from the DRC’s Orientale province (where two smaller and less active Ugandan rebel groups, the Allied Democratic Forces and the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda, are also based). Similarly, between December 2001 and December 2006, about 6,700 FDLR combatants and an equal number of dependents returned to Rwanda from bases in the DRC.

But some feared that if they gave themselves up they would face charges. Several top leaders of the LRA have in fact been indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes. It is also believed that between 200 and 300 commanders and long-time fighters of the FDLR took part in the Rwanda genocide. Those with greater responsibility could be prosecuted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, based in Tanzania, while the rest may face charges in Rwandan courts.

Ironically, as the more moderate elements of both groups agreed to repatriate, their leaderships were left increasingly in the hands of such hard-liners. They actively sought to discourage repatriation by executing many of those caught trying to leave.

Acknowledging the particular challenges in the eastern DRC, the UN Security Council decided in December 2008 to authorize MONUC to help forcibly disarm foreign armed groups, so as to advance efforts to demobilize and repatriate their fighters. That decision came just as the Congolese government invited in troops from Uganda and Rwanda to go after the LRA and FDLR, respectively. By the time the Ugandan and Rwandan armies pulled out in late February, several hundred fighters of the two groups had been killed and scores of commanders captured.

By making it harder for the surviving rebel commanders to communicate with each other, those military operations also created a “temporary vacuum” that loosened the leaderships’ overall control, explains the UN’s Mr. Donat. “It allowed some mid-level FDLR leaders to have some leeway.” With MONUC providing security and logistical support, those who favoured returning home finally saw a chance to make their move.

“I always wanted to come back” to Rwanda, said Joseph Karege, an FDLR soldier. But he feared execution as a deserter. Then, with the Rwandan and Congolese army operations in North Kivu, “War provided the room to manouevre,” he explained, allowing him to successfully return to Rwanda in mid-February.

Though somewhat weakened and dispersed, both the FDLR and LRA continue to attack Congolese civilians, and many villagers have been displaced by the ongoing fighting. Mr. Donat, who has since moved from MONUC to the DDR section of the UN’s peacekeeping department in New York, hopes the problem will diminish over time. He finds it particularly encouraging that many thousands of Rwandan refugees have also chosen to return home. By repatriating refugees, he observes, “you are also diminishing the pool of civilians from which the armed groups can recruit.”

MONUC peacekeepers and Congolese troops are now maintaining military pressure on the FDLR and LRA. Those foreign fighters who remain in the Congo “must disarm and return home,” said Alan Doss, the UN special representative for the DRC, during a visit to North Kivu in late April. “MONUC is ready to help them return safely.”

During an earlier visit, Mr. Doss praised a group of FDLR combatants who had turned themselves in for repatriation. By giving up their arms, he said, they “have chosen a better future.” And when security is restored in the area, he added, it would become possible for the Congo and UN to begin “the real battle, the economic and social development of the population.”

Former Rwanda exiles should ‘feel at home’

Benoït Barabwiriza returned to Rwanda in January for a short visit with several other former combatants and some of their wives and children. It was the first time in a number of years that he had seen his homeland. “We have come here to assess how the country is doing,” he explained to a journalist, “after which we will go back to our colleagues in Congo and tell them of our experiences. Then we will decide whether to come back for good.”

Mr. Barabwiriza is a member of a splinter group from the Front démocratique de libération du Rwanda (FDLR), the Hutu rebel force that opposes the government of Rwanda. For several years the government has been seeking to convince such exiles — disenchanted rebels or civilian refugees — that they are welcome back. Such outreach efforts are part of a broader process of national reconciliation intended to reknit social ties torn apart by the 1994 genocide, in which some 800,000 Rwandans, mostly from the Tutsi ethnic group, were slaughtered.

In December 2001, the Rwanda Demobilization and Reintegration Commission (RDRC) decided to expand an ongoing military demobilization programme to also embrace the government’s former enemies. These included ex-soldiers of the Forces armées rwandaise (FAR) — the army of the regime in power at the time of the genocide — and former combatants of the Rwandan rebel groups that later emerged in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Over the next five years, some 13,000 ex-FAR soldiers were demobilized and given small financial settlements to help their social and economic reintegration. More than 6,700 former rebels from bases in the DRC were also demobilized and given reintegration assistance. That aid included cash, scholarships, vocational training, access to credit and other support for setting up small businesses and income-generating projects.

The number of Congo-based rebels who agreed to join Rwanda’s reintegration process was less than half the RDRC’s initial target. The rest remained in the DRC, kept there by the hardline FDLR commanders or fearful of what awaited them back home. In an effort to erode such mistrust, the Rwandan government and the UN have mounted an information campaign to show the group’s rank-and-file members — and Rwandan refugees more generally — that there is little to fear. This campaign has included radio interviews with returnees who describe progress in rebuilding their lives, as well as occasional “go and see” visits by combatants based in the DRC who afterwards inform other exiles of the conditions in Rwanda.

RDRC Chairman Jean Sayinzoga welcomed Mr. Barabwiriza and his fellow visitors, emphasizing that they could go wherever they wanted in Rwanda, including to visit former FDLR combatants who had previously been repatriated. “Feel free,” he told them, “and feel at home.”

Congolese women protest rebel brutalities

In somber silence, more than a thousand women marched through the town of Buta in the Congo’s Orientale province for more than two hours on 2 April. The action, called to protest brutalities against civilians by rebels of the Ugandan Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), was organized by all the women’s associations in the district. At its conclusion, the women staged a sit-in and presented a declaration to local officials and observers of the UN Mission in the DRC (MONUC). The protesters not only denounced the LRA, but also criticized the Congolese government for not acting quickly enough to restore security. They appealed for humanitarian aid for those displaced or victimized, and urged the UN to conduct an investigation.