Seeking the ‘shoots’ of economic recovery

Coffee pickers in Kenya: Across Africa, many workers are losing their jobs as economies slow down

Coffee pickers in Kenya: Across Africa, many workers are losing their jobs as economies slow downHas the economic crisis reached bottom, with slow recovery under way? Or is the world facing continued recession and with it deepening poverty for many Africans? “No one can tell with any degree of certainty whether the worst for the global economy is over,” Donald Kaberuka, president of the African Development Bank (ADB), responded at the opening of the Bank’s annual meeting in Dakar, Senegal, in May. There is consensus among forecasters that global output will decline this year, but they disagree about the depth of the recession and when and how strongly growth will be renewed.

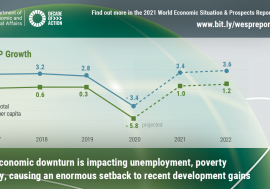

In June the World Bank predicted that the world economy would shrink by 2.9 per cent this year, by more than either its April forecast of a 1.3 per cent drop or projections by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The ADB, in a paper for the May meeting, lowered its forecast for Africa’s growth to 2.3 per cent from the 2.8 per cent it had predicted just three months earlier, amidst fears that “the worst may be yet to come.”

‘Wintry landscape’

That is exactly what worries the United Nations. In a May update to its World Economic Situation and Prospects, 2009, Africa’s economic growth is forecast for less than 1 per cent this year. The UN is less hopeful than some others that the “green shoots” of economic recovery are emerging, Rob Vos, a senior official in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs that produced the report, told journalists. There are few signs of springtime “in this very wintry landscape,” Mr. Vos said.

“For a large number of countries, there are no green shots of recovery,” UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said at the opening of a 24–26 June conference of the General Assembly on the impact of the global crisis on development. “There are only fallow seeds.”

The weak integration of African countries into the world economy initially helped shield the continent from the direct impact of the turbulence in financial markets, UN Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser on Africa Cheick Sidi Diarra pointed out at a special session on Africa and least developed countries (LDCs) during the General Assembly conference. But, Mr. Diarra added, “Most African countries have suffered significantly from the second-round effects arising from the decline in investment, tourism receipts, as well as falling export earnings.” For Africa and the LDCs, “the crisis constitutes a development emergency.”

A poor neighbourhood in Freetown, Sierra Leone: The UN warns that an additional 12–16 million people will be thrown into poverty in Africa because of the economic crisis.

A poor neighbourhood in Freetown, Sierra Leone: The UN warns that an additional 12–16 million people will be thrown into poverty in Africa because of the economic crisis.Because of the crisis, an additional 12–16 million people will be thrown into poverty in Africa, the UN estimates. For the first time since 1994, per capita income will contract for the continent as a whole, the ADB adds.

The major forecasters all agree that economic growth in Africa will again pick up next year. The ADB is predicting a 4.1 per cent upturn in 2010, and the UN report cites forecasts ranging from an optimistic 5.3 per cent to a pessimistic 1.7 per cent. The World Bank sees sub-Saharan Africa growing by 3.7 per cent in 2010, but warns that the risks are “heavily tilted to the downside.”

Years of relatively strong growth and deep policy reforms are helping many African countries weather the present economic crisis better than previous downturns. But the resilience of African economies is limited.

Economic pain

The pain of the global crisis is being felt across Africa. South Africa, the continent’s leading economy, went into recession in the first quarter, contracting by 6.4 per cent compared with the same period a year earlier. Over 180,000 people lost their jobs between December and March, pushing the unemployment rate to 23.5 per cent. Standard Bank predicts that up to 400,000 jobs could be lost in 2009.

Few countries have escaped the impact:

- In Egypt over 100,000 workers were laid off in the six months ending in March, and up to 500,000 could lose their jobs this year.

- In Kenya more than 10,000 workers were laid off in the first quarter.

- Some 12,000 miners have lost their jobs in Zambia.

- In Tanzania some 20,000 horticultural workers face redundancy as demand for vegetables and cut flowers in Europe and the US plummets.

- In Nigeria government revenues are 30 per cent below expectations, largely because of lower oil prices and falling production.

The ADB forecasts that African export earnings will plunge this year by $250 mn. A similar collapse is forecast for foreign investment. Tourist numbers are down just about everywhere, and countries from Senegal to Kenya are reporting lower receipts from citizens working abroad.

With aid levels also vulnerable, more and more governments are facing a cash crisis. From a surplus in national government accounts last year amounting to 2.8 per cent of total output, Africa now faces a deficit equivalent to some 5.8 per cent, according to the ADB. That could mean cancelled development projects and lower social spending.

Most countries are also facing tough export competition. These range from Mauritius — with its relatively sophisticated manufactured exports hit hard by growing competition from China and others even before the downturn — to Burkina Faso, still heavily dependent on cotton and gold.

Uneven impact

Nevertheless, the impact of the global economic crisis is hitting unevenly. According to Mr. Kaberuka, 14 African countries still grew by more than 5 per cent in the first quarter of 2009, and another 13 above the rate of population increase.

Significantly, it is in Africa’s low-income and fragile states, with their lower exposure to the global economy, that growth rates and income are forecast to hold up best, albeit at low levels. The exceptions are countries like Lesotho, Madagascar and Swaziland, which are heavily dependent on trade or migrant labour remittances.

Africa’s major oil and mineral economies are forecast to see the sharpest downturns. The UN forecasts growth in sub-Saharan Africa this year of only 0.9 per cent. But if Nigeria and South Africa are excluded, the region is projected to grow by a slightly healthier 1.5 per cent.

While countries like Algeria, Angola and Botswana are facing significant per capita declines this year, they also have a comfortable financial cushion to help see them through. But many will be cautious about drawing too heavily on their foreign reserves in order to preserve their credit ratings. They will prefer, like Botswana, to access ADB or other multilateral funds.

Signs of recovery?

Despite the gloomy numbers, some analysts see signs of an upturn. The sharp depreciation of many African currencies, which raised import costs, has eased for many. Fund managers working on Africa report that portfolio investors are beginning to look again at prospects on the continent. Both the Nigerian and South African stock exchanges registered higher volumes and prices in April and May, although they remain well down on levels a year earlier.

Commodity prices, usually a bellwether for recovery in most African countries, have shown signs of reviving. Oil and mineral prices have begun to rise. Cocoa and tea prices have been sharply up, but largely because of production problems in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Kenya, which promise little relief for those exporters. Overall, recovery is still modest, and caution remains the watchword.