Africa begins to tap crisis funds

Factory in Nigeria: Donor institutions have promised some financing to help stimulate economic activities in Africa and other poor regions.

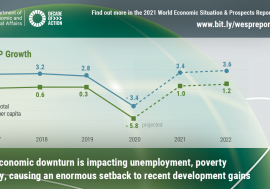

Factory in Nigeria: Donor institutions have promised some financing to help stimulate economic activities in Africa and other poor regions.African countries are beginning to get some of the additional aid and other financing they need to navigate the current economic downturn without lasting damage to vulnerable development programmes. But there is considerable doubt that such funding will be sufficient and timely enough — particularly if the anticipated upturn in world economic growth for 2010 fails to materialize.

The Group of 20 (G-20), a high-level consultative body of the world’s major economies, proposed a set of measures to deal with the crisis at a 2 April meeting in London. But its proposals have met with a mixed response. While significant, the steps pledged by the G-20 “may not be enough to meet the challenges posed by this worldwide crisis,” warns the UN’s World Economic Situation and Prospects, 2009. Altogether, some $50 bn would be available to low-income countries. Yet how much of what the G-20 offered is new and how much of it Africa will receive and when remains unclear, said the Africa Progress Panel, an advocacy group, in a June report.

While it promised stimulus measures to help kick-start renewed growth, the G-20 meeting was short on details. It focused instead on measures to strengthen the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) so that it could lend more to countries affected by the crisis. In addition, the G-20 pledged support for increased lending by regional banks like the African Development Bank (ADB), and more trade financing (see box).

IMF Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn visiting Tanzania: The Fund is promising to impose less exacting conditions on its lending to African countries in crisis.

IMF Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn visiting Tanzania: The Fund is promising to impose less exacting conditions on its lending to African countries in crisis.Action on the IMF would treble its resources, allocate to all member countries additional Special Drawing Rights (SDRs, the Fund’s monetary unit), provide greater and speedier concessional lending (with fewer conditions) and strengthen surveillance of the economic policies of all members (including the wealthiest). The G-20 leaders also expressed support for reform of the IMF and its sister institutions, “including a greater voice and representation” for developing countries.

‘Rich countries can do more’

A retooled and replenished IMF with greater political oversight would represent “a great victory for Africa,” then South African Finance Minister Trevor Manual said in mid-April.

Other African officials welcomed the G-20 measures, but urged further action. “The general impression is that the rich countries can do more to assist developing countries,” Tanzanian Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs Mustafa Mkolo told journalists at an April meeting of the Fund and World Bank in Washington.

IMF Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn has confirmed that Africa can expect a doubling in its concessional lending to some $6 bn over the next two–three years. The World Bank has established a $2 bn quick-dispersal facility for crisis-affected countries, while the ADB has created new emergency liquidity and trade finance facilities to help its members.

In late May, Kenya and Tanzania accessed the IMF’s new Exogenous Shocks Facility (ESF), set up to help countries with sudden crises caused by external factors. According to the Fund, lending to Africa totalled $1.5 bn by the end of May, both from the ESF and from existing poverty-reduction support programmes.

‘More breathing space’

The Fund says it is also easing the conditions it imposes on lenders and doing more to preserve social programmes through better targeting of spending and subsidies to ensure that the vulnerable directly benefit. Government budgetary targets have been eased in 80 per cent of African countries, Mr. Strauss-Kahn claimed, “giving them more breathing space to adjust to the crisis.”

Implementation of the agreement for a new allocation of SDRs awaits formal approval by the IMF Board of Governors. But once the allocation is made it will automatically boost Africa’s foreign exchange reserves by some $16 bn, helping to steady the nerves of central bankers and investors.

The ADB’s shareholders at the May annual meeting agreed to begin discussions on a possible expansion of the bank’s capital. The bank is scheduled to increase lending annually by 14 per cent. At the meeting the ADB, the World Bank, the Development Bank of Southern Africa and a number of bilateral lenders announced a coordinated strategy to make some $15 bn available for key sectors like infrastructure.

The ADB is also mobilizing more trade finance, as is the World Bank’s private-sector affiliate, the International Finance Corporation. The drying up of trade financing has had a major impact on Africa, says Mr. Kaberuka. As the G-20 meeting was under way, the World Bank announced the launch of a coordinated initiative between multilateral and bilateral lenders to make an initial commitment of $5 bn available.

Aid uncertain

Despite the new initiatives, aid prospects continue to be mixed. Aid to Africa in 2008 rose by some 10 per cent. But this was after declines in the previous two years. As the African Union and the UN Economic Commission for Africa point out in their Economic Report on Africa 2009, aid levels are well down on the $72 bn a year considered necessary to meet the Millennium Development Goals set by world leaders in 2000.

The new administration in the US has said it will double aid over the next five years. The UK has pledged to maintain commitments, and Denmark has pledged $3 bn for youth employment and private sector investment. However, the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the industrialized countries’ Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development acknowledged in late May that some members have already decreased their aid and that others are unlikely to meet their commitments.

Even if aid budgets are not cut, the World Bank says that some $5 bn could be lost this year as a result of exchange rate losses among DAC members alone. In its latest Global Development Finance report, the Bank warns that the additional aid that Africa has received has not been sufficient to close the widening financing gap, which is expected to reach $30–40 bn this year.

Longer-term needs

But short-term cash also carries dangers, the ADB warns in a paper at its annual meeting. The promise of scaled-up resources is a “mixed blessing,” with many countries forced to borrow. This, it fears, could lead to renewed debt, possibly undermining recent advances in lowering the continent’s debt burden. The bank also warns of a risk that resources may shift towards crisis responses to the detriment of long-term development programmes.

To ensure that Africa’s development needs are kept in focus, leaders have been urging a strengthened voice — and voting power — in the international financial institutions and other forums. Measures to date still do not sufficiently take into consideration developing countries’ concerns, Nigerian Foreign Minister Ojo Maduekwe complained after attending a meeting of the finance ministers of the Group of Eight in Italy in June.

Some tentative steps are being taken, such as sub-Saharan Africa’s acquiring a third seat on the executive board of the World Bank. But the pace and extent of change remains unclear.

Some critics have urged new or at least more democratic institutions, more regulation and different policy prescriptions. The European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad), a coalition of 55 non-governmental organizations, argues that the IMF is still promoting stringent fiscal and monetary policies in poor countries to meet the financial gaps caused by the crisis.

A 24–26 June UN General Assembly conference on the impact of the crisis on development heard numerous calls for major reforms in the international financial system. “The crisis exposed the need for a greater voice for developing countries in how the international financial system is operated and regulated,” said Gambian Vice-President Isatou Njie-Saidy. “For a crisis that we did not trigger, but for which we bear the greatest burden,” she added, “it is absolutely logical that decisions about us be taken with our full participation.”

G-20 promises

At their April meeting, the G-20 members agreed to make available $1,100 bn to help support renewed economic growth. Areas of agreement included:

- Trebling the resources of the IMF to $750 bn

- A new $250 bn allocation of the IMF’s currency, the Special Drawing Right

- Increased lending by the multilateral development banks of at least $100 bn

- A $250 bn increase in trade finance

- Doubling the IMF’s concessional lending capacity

- Strengthening the IMF’s monitoring and surveillance role

- New flexible lending by the IMF and World Bank

- Reform of the international financial institutions to give better representation for emerging and developing economies