New WTO proposals stir controversy

New WTO proposals stir controversy

On the way to industrialization, developed countries utilized a number of state intervention measures. These included favouring local over foreign companies, directing investment towards certain sectors and restricting market competition for the benefit of domestic enterprises. However, under a highly controversial set of proposed new agreements at the World Trade Organization (WTO), industrial nations are seeking to end many such arrangements, denying developing countries the option of using them.

Known simply as the “ Singapore issues,” the proposals are emerging as thorny obstacles to the current round of trade negotiations, pitting developing against industrial nations. Disagreements over the four issues — trade and investment, trade and competition policy, transparency in government procurement and trade facilitation — contributed to the collapse of a crucial WTO meeting in Cancún, Mexico, in September (see Africa Recovery, October 2003).

At present, a country may grant preferences to domestic companies by taxing them less or allowing them to utilize domestic distribution channels barred to foreign firms. However, “proponents of the Singapore issues in the WTO would particularly target these and other similar flexibilities,” warns former Indian Ambassador to the WTO Bhagirath Lal Das. His country leads a group of mainly developing countries, many of them in Africa, that are opposed to launching negotiations on the Singapore issues at the WTO as part of the current round.

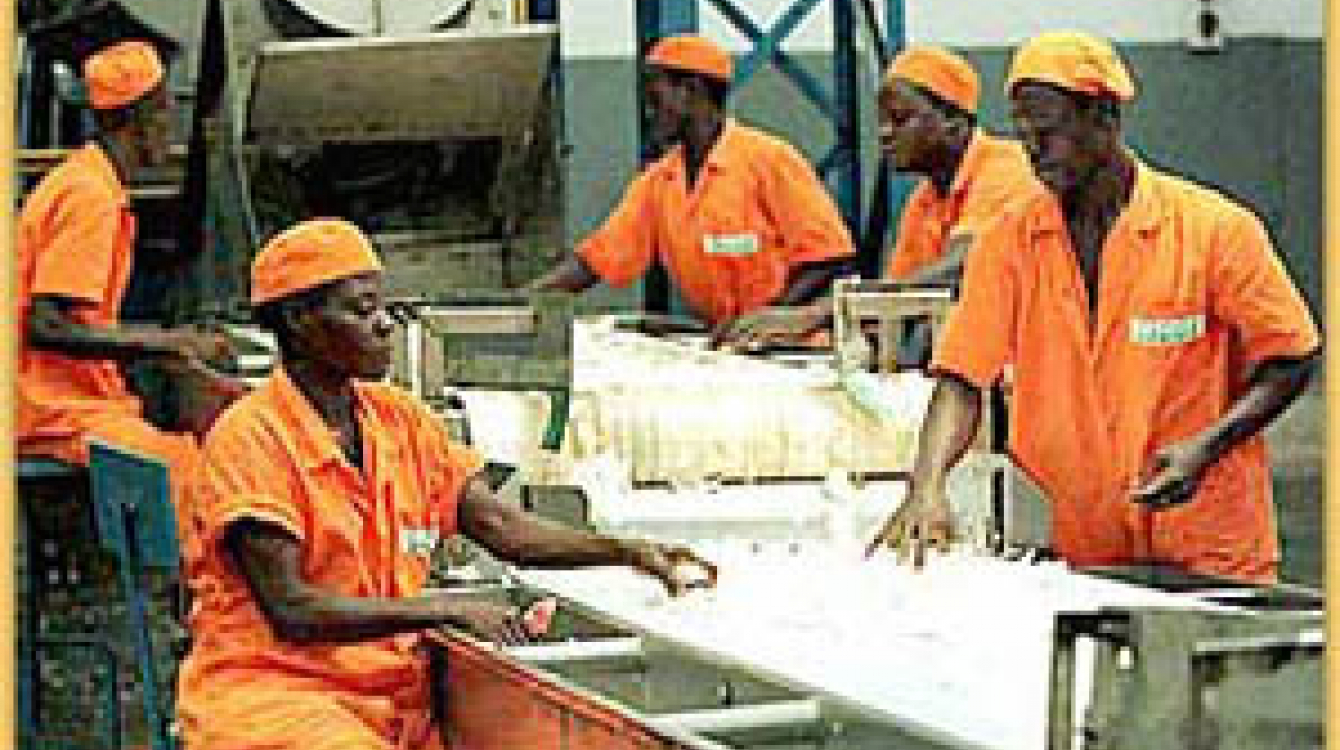

Agricultural processing factory in Côte d'Ivoire: to be able to industrialize, African countries want the same kind of domestic protection measures that developed countries have utilized.

Photo: © AfricaPhotos.com

Kicking away the ladder

“The large industrial economies had effective protection from competition long after their industry took root, through explicit or informal rules, or from being first into a market,” notes Mr. Bill Rosenberg, a trade and investment analyst from New Zealand . “That greatly helped their development.”

Japan's highly restrictive policies on foreign direct investment are well-known. It began relaxing them during the 1960s, allowing a maximum of 50 per cent foreign ownership in 33 industries where Japanese firms were already well established. Full foreign ownership was permitted in only 17 sectors where Japanese companies had achieved a dominant position at home and a strong foothold abroad.

Having had a head-start, industrial countries are now “proposing to kick away the ladder they used, to prevent other countries from ascending it,” says Mr. Rosenberg.

The four issues, pushed mainly by the European Union (EU) and Japan, were first brought up for negotiation at the WTO during a ministerial conference in Singapore in 1996. (Ministerial conferences are the WTO's highest decision-making gatherings and are held every two years.) Industrial nations pushed for agreements that would be binding on all WTO members. But many developing countries refused, unconvinced of the need for increasing their WTO obligations and wary of the possible consequences to their development policies. Many were more concerned about ironing out outstanding issues from the previous round of trade talks, the Uruguay Round, concluded in 1994. A compromise was reached, with the Singapore conference agreeing to set up four working groups to study and clarify the new issues. Since then, pressure to transform the study groups into negotiating committees has been growing.

The first Singapore issue, a proposed trade and investment agreement, seeks to expand the rights of foreign investors. The second, on trade and competition, would regulate “hard core” cartels and require the creation of national rules to ensure free competition among foreign and domestic companies. Trade facilitation, the third proposal, involves establishing rules to simplify and lower the costs of customs procedures. Under the fourth proposed agreement, on transparency in government procurement, member states would be required to publicly announce bids for supplies purchases and allow competition between domestic and foreign companies seeking to provide them.

Developing countries regard the first two issues as potentially damaging. “Many countries still do not see the need or the use for a multilateral agreement on investment or competition, while many can see the benefit of agreements on transparency in government procurement and trade facilitation,” says Dr. Youssef Boutros-Ghali, Egypt's trade minister. But, he says, even the latter two agreements “have to be drafted so as to take into account the capacities, constraints and needs of developing countries.”

Trade and investment

The push for a single multilateral agreement on foreign investment comes at a time when international capital flows are rapidly increasing. Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows rose from $203 bn in 1990 to $735 bn in 2001. While FDI may stimulate economic growth, countries often attempt to ensure that it falls in line with national development goals and does not undermine local enterprise. In 1962, the UN acknowledged the right of states to regulate the behaviour of foreign investors. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), more than 2,100 bilateral (government to government) treaties currently regulate FDI flows.

It is common for countries to support the development of local industry, for instance, by offering incentives to domestic companies. Some have regulations restricting foreign ownership of certain “strategic” sectors such as the media, telecommunications, aviation and atomic energy. Others require joint ventures with domestic companies, the hiring of local workers, restrictions on remittances and mandatory technology transfers, to maximize the benefits of foreign investment.

Daimler-Chrysler auto plant in South Africa : New WTO proposals seek to minimize regulation of foreign companies.

Photo: © Das Fotoarchiv / Markus Matzel

Proponents of liberalization argue that such regulations impede the free flow of capital. And as international investors aggressively seek to set up shop in countries that offer the best returns, there is pressure to erode many such national measures. Most current investment agreement proposals aim to remove regulatory practices perceived as discriminating against foreign investors in the host countries, notes Mr. Kavalji Singh, director of the India-based Public Interest Research Centre. Recently, he says, there have been several efforts to establish multilateral policies on investment, most notably the failed attempt by the industrialized countries' Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in the 1990s to negotiate a Multilateral Agreement on Investment (see box, at bottom of page).

Easing regulation

The proposed WTO agreement on investment would seek to reduce controls known as performance requirements, conditions that foreign companies must meet if they are to continue operating in a given country. These may include meeting production or export quotas or purchasing inputs locally. Critics of the WTO proposal say eliminating such measures would reduce the ability of governments to utilize investment for national development goals.

Yet many industrial nations have benefited from similar measures. When car maker Nissan established a plant in the UK, it was on condition that 60 per cent of the value of the goods it made would come from local inputs, a proportion that would eventually rise to 80 per cent.

“Our strongest arguments still remain that the WTO is not the right forum, that the traditional WTO principles of non-discrimination, particularly national treatment [equal treatment for both foreign and domestic industry] are not appropriate for a development policy-related issue like investment,” says India's Industry Minister Arun Jaitley. “Trade negotiators are not the right people to deal with movements of capital that have dynamics of their own.”

Governments opposed to a WTO investment agreement are also concerned about signing away power over domestic policies to foreign corporations. Transnational corporations are generally large, some with assets greater than the economies of entire countries. Belief that some corporations now wield more power than many developing countries is fuelling concerns about how to regulate them. An often cited example is the investment agreement signed by Canada, Mexico and the US under the North American Free Trade Agreement. The agreement confers unprecedented powers to foreign investors and all three governments have either been forced to reverse domestic policy decisions or face suits by foreign investors.

Some countries that are reluctant to enter into a WTO investment agreement argue that they have already done a lot to improve their investment climates. Between 1991 and 2001, for instance, more than 95 per cent of the 1,400 regulatory changes to national investment policies were aimed at creating a more favourable environment for FDI, reports UNCTAD. The majority of these were carried out autonomously. “Today, nearly all countries have removed entry restrictions and limitations on foreign equity shares in manufacturing,” concurs Mr. Richard Newfarmer, a World Bank economic advisor.

Trade and competition policy

Those calling for a WTO agreement on competition policy would like it to regulate hard core cartels, which they blame for anti-competitive practices such as price-fixing. It would also restrict monopolies, mergers (that limit competition) and arrangements between suppliers and distributors that close out markets from other competitors. It is estimated that developing countries bought products worth $11 bn annually from cartels during the 1990s. The WTO notes that these cartels often mark up the price of their products by between 10 and 45 per cent. In a submission to the WTO study group on competition, the EU notes that it envisages an agreement that places an “obligation for WTO members to enact in their domestic competition law a ban on hard core cartels.”

But, says Ms. Cecilia Oh of the Ghana-based Third World Network-Africa, there is no generally accepted definition of a hard core cartel. Also, the assumption that all such cartels have an adverse impact on development is questionable. “The experience of some Asian countries in which cartelization was, for a time, an element of their industrial policies, challenges this assumption,” says Ms. Oh. In addition “nearly all developed countries have had exemptions on the basis of overriding economic or public interest grounds.” Some governments also allow cooperation by small or medium-sized enterprises to counteract the market power of a dominant company. At various stages, countries such as Korea encouraged various cartel arrangements and mergers among domestic companies in order to compete against the might of Western firms.

Meanwhile, industrial countries maintain policies that shelter their own companies from foreign competition, in direct conflict with standing WTO rules. Only under threat of economic retaliation by the EU did US President George Bush lift tariffs on steel imports in December. He had imposed them 21 months earlier to shelter US producers from foreign competitors and “give the industry a chance to adjust to the surge in foreign imports,” he said.

India's industry minister, Mr. Jaitley, says countries at different stages of development view competition issues differently, based on the effects they have on their economies. He believes agreement on these issues can only occur between countries at similar stages of development, and that WTO membership is too diverse to allow a framework that would be suitable for all.

Transparency in government procurement

n agreement on government procurement already exists within the WTO. It was originally negotiated during earlier trade talks in the 1970s. However, it is one of only four WTO agreements known as “plurilateral” — they only bind willing participants. Just 28 WTO members, mainly industrial nations, signed onto the existing agreement. Only they are required to treat foreign and domestic suppliers of government purchases equally. Current attempts to establish a new agreement are aimed at extending some of the existing provisions to all WTO member countries.

The current agreement also requires member countries to ensure that adequate information on procurement is made available and decisions are taken fairly. “It requires publication of laws, regulations, judicial decisions, administrative rulings and notices of invitation to participate in covered procurement,” writes Mr. Joseph Finger, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC . Developing countries fear that if the agreement were extended to them, they would have to establish new bureaucratic procedures and enact new legislation, both burdensome and costly.

Discussions in the WTO study group currently focus on the scope and definition of government procurement, what, if any, exemptions would be extended to developing countries and issues of technical assistance for poorer countries. The chairman of the group reports that most developing countries say they lack sufficient skills to properly negotiate an agreement in this area and are requesting clarity on its implications before participating.

Trade facilitation

The proposed agreement on trade facilitation seeks to cut red tape at the borders by simplifying import, export and customs procedures. It also aims to increase transparency, for instance by requiring the publication of trade regulations. UNCTAD estimates that the average customs transaction is handled by 20-30 different parties, requiring at least 40 documents and the re-input of 60-70 per cent of all data. As global tariffs begin to fall under the WTO's international trade rules, it is becoming apparent that at times the cost of complying with customs formalities is exceeding that of the duties on a product. Consumers end up paying higher prices.

Many developing countries broadly support the objectives of the trade facilitation agreement, but are unprepared for new legal commitments that would stretch their already limited resources. They also disagree with their industrial counterparts over how trade facilitation measures would be framed under the proposed agreement. For instance, many oppose an agreement that would bind them to dispute settlement — a WTO procedure for settling violations that is legally binding and that can recommend compensation or trade sanctions.

Mounting pressure

Since the Singapore ministerial meeting in 1996, pressure to launch negotiations on these issues, especially from the EU and Japan, has been growing. Japanese Foreign Minister Yoriko Kawaguchi says agreements on the Singapore issues would benefit all, including developing countries, by establishing uniform rules in these areas while also allowing for enough policy space for development. “Our aim is to maximize the benefits of globalization and minimize its negative effects,” he says. “That is because globalization with rules is far better than globalization without.”

At the WTO's 2001 ministerial conference in Doha, Qatar, developing countries, led by India, continued to argue against launching negotiations on the Singapore issues. The disagreement almost resulted in the collapse of the Doha meeting and a failure to launch a new round of trade negotiations. At the last minute, developing countries conceded, on condition that negotiations on the new issues would only begin “on the basis of a decision to be taken, by explicit consensus,” in Cancún.

he September 2003 ministerial meeting in Cancún marked the mid-point of the Doha round. Despite the round being dubbed the Doha Development Agenda, poor countries noted that deadlines on all the issues of primary importance to them had been missed. Indeed, subsidies in agriculture were still on the rise, despite promises by industrial nations to reduce them. A grouping of 70 developing countries, led by Malaysia and including many African countries, refused to give the go-ahead to launch negotiations on the new issues, contributing to the impasse in Cancún.

Botswana's Trade Minister Jacob Nkate warned in Cancún that there was a need for “realism and pragmatism, given the complexity of these issues and the limited institutional, human and technical capacities in most of our countries.” Speaking on behalf of the African, Caribbean and Pacific group of countries, Mr. Nkate called on the WTO to “continue the clarification and study processes in these areas in order to enable us to have a deeper understanding.”

Collapse of the Multilateral Agreement on Investment

During the 1990s, big capital-exporting countries intensified efforts to establish a Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a grouping of rich countries. Negotiations began in 1995. Once completed, the agreement would also be open to a number of developing countries, which were invited to participate as observers.

But the talks came under intense global criticism by non-governmental organizations and trade unions, which charged that the agreement would undermine domestic policies, threaten the environment and work against fair labour practices. Opponents argued that rich countries, which had benefited from protectionist investment regimes in the past, were now seeking to remove such regulations, impeding the development prospects of poor countries.

While at the beginning there was general consensus among OECD countries about the need for such an agreement, a number of differences soon emerged among them. For instance, while the EU and Canada preferred negotiations to be moved to the WTO where the agreement would be provided with a legally binding dispute settlement mechanism, the US did not. The negotiations eventually collapsed in November 1998.