African media breaks ‘culture of silence’

African media breaks ‘culture of silence’

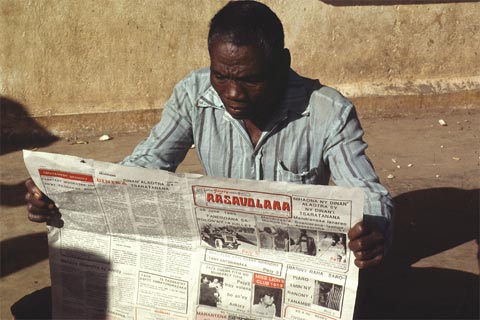

Reading a newspaper in Madagascar: Since the early 1990s, independent newspapers have broken government monopolies on the press, but in many countries the media remain under threat.

Reading a newspaper in Madagascar: Since the early 1990s, independent newspapers have broken government monopolies on the press, but in many countries the media remain under threat.When on 18 March this year the Daily Nation, one of Africa's biggest and most successful independent newspapers, celebrated its 50th anniversary, Charles Onyango Obbo, a columnist for the Nairobi, Kenya, paper, wrote, "It has mostly been hell on earth for the African media for most of these 50 years. In fact the freest period for the African media generally has been the 15-year period between 1990 and 2005."

The media boom of the late 1980s and early 1990s, accompanying the movement for democratic reforms in Africa, transformed the continent's media landscape virtually overnight. It ended near-absolute government control and monopoly and ushered in a vibrant pluralism. Suddenly the streets of Africa's capitals were awash with newspapers. The "culture of silence," imposed first under colonialism and then by post-colonial military dictatorships and autocratic one-party states, was rudely broken.

Independent media boom

At independence in 1960 most newspapers were privately owned, organs either of the nationalist political movements and parties or of businesses mostly established by European investors. But by 1970 most newspapers of any significance across the continent were government-owned. Any newspaper expressing independent editorial attitudes was censored, banned or so controlled that most of the owners gave up publishing. Besides apartheid South Africa, only Kenya and Nigeria accommodated private and independent press businesses, even then under enormous political constraints.

In a few countries, such as Gambia and Niger, the first daily newspapers appeared in the period of media liberalization and boom. One man, the Liberian journalist Kenneth Best, started the first daily in Liberia (1981) and the first daily in Gambia (1992). Mr. Best eventually had to flee both countries.

Since the 1990s the independent media have grown like the savannah grass after prolific rainfalls following a long drought. In West Africa, according to a 2006 study sponsored by the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), there were over 5,000 newspapers and radio and television stations in 15 countries.

By far the most earth-shaking development was the burst of radio stations. From the capitals to the provinces, the booming force of private and independent voices initially threatened to drown out the states' authoritarian broadcasting systems. In semi-desert Mali, for instance, there are today nearly 300 radio stations. In the war-ravaged Democratic Republic of the Congo there are about 196 community radio stations. Across the continent, the Internet and mobile telephony augment old media to expand Africans' sources of information and means of mass communication.

The armed conflicts of the 1990s did not seem to hinder the emergence of independent media anywhere, although many media outlets did become targets. Somalia saw the emergence of its first independent press, radio and even TV after it plunged into continuing anarchy. Numerous stations and newspapers emerged in Liberia and Sierra Leone during their notoriously bloody conflicts, while the state-owned broadcasting systems all but collapsed.

Today, two decades since the media boom, Eritrea is about the only country in sub-Saharan Africa in which government has a total monopoly on press and broadcasting.

A DJ on Mozambique’s Radio Komati: The radio is crucial for reaching audiences in Africa’s rural areas, and sometimes in their own indigenous languages.

A DJ on Mozambique’s Radio Komati: The radio is crucial for reaching audiences in Africa’s rural areas, and sometimes in their own indigenous languages.Strengthening democracy

Linus Gitahi, chief executive of Kenya's Nation Media Group (NMG), said at the Pan-African Media Conference during the Daily Nation's anniversary, "More Africans live in relative freedom today than they did 50 years ago."

No doubt the media's role has been central in strengthening democracy in those countries where there has been tangible progress in governance and respect for human rights.

Weak though they may often be, the media, especially the independent outlets, have made remarkable contributions to peaceful and transparent elections in Benin, Cape Verde, Ghana, Mali, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia; to post-conflict transitions and the restoration of peace in Liberia, Mozambique and Sierra Leone; and to sustaining constitutional rule in times of political crises in Guinea, Kenya and Nigeria. And many continue to push to open up the space for freedom in suffocating environments.

Radio has expanded local news and information production. And the mobile phone has enhanced citizens' participation in public affairs discussions on the air. Radio, by incorporating many local languages more widely, has promoted positive cultural identity in many communities. At the 10th anniversary this January of Ghana's Radio Ada, a community station at Ada, a coastal town about 100 kilometres from the capital, the chief lamented, "Until the station came here, we did not hear our language on radio. We did not feel that we belonged in Ghana."

In some cases, however, the media have been an instrument of hate, xenophobia and crimes against humanity. While Rwanda's Radio Milles Collines, which played a role in the country's genocide, is the most known, there have been other disturbing examples of media promotion of ethnic hate, as in the bloody aftermath of Kenya's 2007 elections. Even in Ghana's much-celebrated successful election in 2008, some radio stations incessantly preached violence and mobilized partisan mobs to attack opponents. In all such cases the perpetrating media were owned by or were supporters of powerful persons in government, political parties or factions in conflicts.

Continuing repression

The progressive thrust of the media has generally come up against violent repression. When the media have dared to question or uncover criminality and corruption in high places, they have usually earned the extreme wrath of "where power lies."

Thus virtually all assassinations of journalists, such as that of Norbert Zongo in Burkina Faso in 1998, Carlos Cardoso in Mozambique in 2000 or Deyda Heydara in Gambia in 2004, have had similar motives. The report of an independent commission on the Zongo case concluded that "Norbert Zongo was assassinated purely for political reasons, because he practiced committed investigative journalism. He defended a democratic ideal and was committed, through his newspaper, to fight for the respect of human rights and justice against bad governance of the public goods and against impunity."

Various international media rights advocacy groups, such as the New York–based Committee to Protect Journalists, calculate that around 200 journalists have been killed in Africa in the last two decades. The majority of the victims fell in circumstances of war.

The use of repressive legislation has been a major tool in reversing the media's freedoms. Outside of South Africa, where the post-apartheid transition included fundamental reforms in media legislation, the new atmosphere of media pluralism elicited very negligible legal and policy reforms beyond constitutional clauses reaffirming UN principles on free expression.

By 2005 legislative and policy frameworks in most countries were so constraining that the ECA said in a study, "The need for a critical review and overhaul of the legal and policy environment in which the media operates across Africa cannot be overstated."

While individual countries may not have made significant reforms to media legislation and policy, the African Union and regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Southern African Development Community and the 11-member Regional Conference of the Great Lakes have all adopted binding protocols and declarations advancing press freedom and freedom of expression.

Most member governments may be violating or ignoring the protocols they have signed, but civil society groups use institutions such as the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information of the African Commission on Human and People's Rights to promote media rights. Some, such as the Media Foundation for West Africa, also use the new regional ECOWAS Community Court of Justice to challenge violations of journalists' rights.

Constraints and limitations

If violent attacks and disabling laws have been used to arrest the media's growth and relevance, professional and financial weaknesses have tended to limit their impact.

Despite the phenomenal growth of the media, Professor Guy Berger of the Rhodes University School of Journalism and Media Studies in South Africa insisted in 2007 that "Africans are the least-served people of the world in terms of the circulation of information, for the reason that this continent exhibits a mass media that is everywhere limited in terms of quantity, and also sometimes quality."

Professor Berger noted, for example, that Africa had the world's lowest number of journalists per capita. South Africa, the continent's highest performer, had one journalist per 1,300 citizens, while Ghana had one per 11,000, Cameroon one per 18,000, Zimbabwe one per 34,000 and Ethiopia one per 99,000.

The huge deficit in trained professionals keeps increasing, despite donor support for short ad hoc courses and the emergence of private training schools.

Of all the constraints and limitations, economic factors appear to be the most critical threat to the survival of media pluralism. Most media outlets remain small operations, with poor business management capacity. But a few like the NMG in Kenya and Multimedia in Ghana have expanded investment into other media, and extended operations across borders into other countries. Yet while a few are growing into huge, multimedia transnational conglomerates, many face the possibility of shrinkage and perhaps extinction.

As media pluralism grows and African economies open up, the media's growing dependence on the market threatens to limit editorial independence. Businesses that are visibly dominant in advertising and sponsorships are reported by journalists to be exerting pressure on media to do their bidding, such as by killing stories unfavourable to the businesses.

Such pressures and attacks on press freedom have also propelled the emergence of advocacy and defence organizations across the continent. The Media Institute of Southern Africa in Windhoek, the Media Foundation for West Africa based in Accra, the Media Rights Agenda of Nigeria and Journalists in Danger in Kinshasa are among the best known. National and regional professional journalists' associations have also stepped up their defence of media professionals.

Although state broadcasting persists, dominating the airwaves in most countries, independent and pluralistic media in Africa are here to stay, despite the many challenges. And that may be the guarantee of the growth and strengthening of democracy in Africa.

Professor Kwame Karikari is executive director of the Media Foundation for West Africa, headquartered in Accra, Ghana, and heads the School of Communication Studies at the University of Ghana.