Young Africans put technology to new uses

Young Africans put technology to new uses

Young Kenyans pioneered the use of cell phone calls and text messaging to monitor political conflict, and their “Ushahidi” software is now used in different parts of the globe for humanitarian relief, election monitoring and other purposes.

Young Kenyans pioneered the use of cell phone calls and text messaging to monitor political conflict, and their “Ushahidi” software is now used in different parts of the globe for humanitarian relief, election monitoring and other purposes.At 11 p.m. on 2 January 2008, back from Nairobi, Kenya, an exhausted Ory Okolloh — a Johannesburg-based Kenyan lawyer in her thirties — posted the following message on her blog: “For the reconciliation process to occur at the local level the truth of what happened will first have to come out. Guys looking to do something — any techies out there willing to do a mashup of where the violence and destruction is occurring using Google Maps?”

For most of the previous week, post-election violence had flared up in Kenya, leaving scores of people dead. Ms. Okolloh herself had left the country in an evacuation. “The trip to the airport was one of the scariest moments in my life,” she wrote on her blog.

Live media broadcasts had been suspended and, among the large Kenyan diaspora around the world, many relied on bloggers like Ms. Okolloh to follow what was happening in their country. “I was updating my blog almost every five minutes,” she recalls. But she soon realized that more information was needed and launched the appeal. A flurry of contributions by dozens of compatriots followed. One person suggested a webpage listing casualties with details on where and how they had died. Another envisaged posting information on displaced persons in need of help. “It could help raise awareness,” he explained.

Days later, after many other such postings, Ms. Okolloh, along with four young bloggers from Kenya, launched the website Ushahidi, a communication forum that allows anyone to report cases of violence through text message, e-mail or web submission, and to portray the information on an online map. In order to ensure reliability, one member of the team used government sources, aid groups’ information and press reports to verify events submitted to Ushahidi (“testimony” in Swahili).

Ushahidi illustrates how young Africans are using new technologies to enter the political arena. According to a study by Harvard University scholars*, Ushahidi has been the most comprehensive tool in gathering crisis-related information in Kenya. The platform, the report adds, performed better than mainstream media by reporting more cases of violence and covering a wider geographic area.

Although the website was intended mainly to get the word out about the crisis in Kenya, it also functioned as a gateway for increased political participation. Using their cell phones, ordinary citizens helped counter rumours and what they perceived to be official underestimations. They were able to help record trends and patterns of violent incidents.

Democratizing information

In an e-mail to Africa Renewal, Erik Hersman, one of Ushahidi’s co-founders, affirms that the “only goal was to create a simple means for ordinary Kenyans to say what was going on.” The idea, he adds, was “to democratize information in what was a very closed media at the time.”

Juliana Rotich, another Ushahidi co-founder, shares that view. Yet she notes the limited impact the platform had within Kenya at the time. No communication campaign was designed to help people learn about the platform. Those who used it were mostly people already connected to the Internet regularly. “We were not able to reach a critical mass of people in the country, partly because we did not get much local awareness,” Ms. Rotich told Africa Renewal. “But at the same time, it did help since no one threatened to shut us down.”

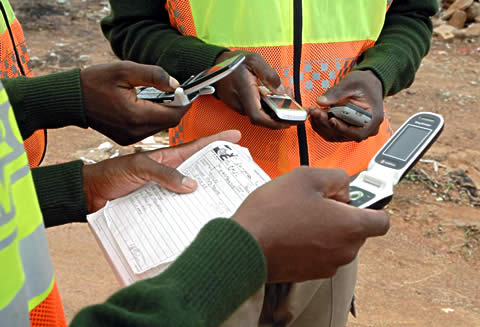

Non-governmental peace workers sharing information by cell phone to help monitor

Non-governmental peace workers sharing information by cell phone to help monitorand prevent violence in the South African township of Soshanguve, near Pretoria.

By allowing young Africans to contribute to ongoing discussions and events, new technologies provide them with unparalleled access to political debate. “In the African context, being able to voice one’s opinion freely is not that easy, especially for young people,” comments Théophile Kouamouo, who has run IvoireBlog, a lively blogging platform in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, since December 2007. Having set up Abidjan Blog-camps, a training seminar in which bloggers from around the country regularly share views and experiences, Mr. Kouamouo believes that African bloggers are walking in the steps of independent media outlets that led the battle for free speech in the early 1990s. “This is part of our efforts in building a democratic society,” he explained to Africa Renewal.

A similar site CongoBlog was launched in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) by Cédric Kalonji, a young citizen journalist from Kinshasa. He too aims at providing better access to the public sphere for young Congolese. CongoBlog has lately come to function like a news agency, with correspondents based in all regions of the country.

Speaking to Africa Renewal, Ms. Okolloh of Ushahidi notes that in the digital arena “the barriers to entry are generally lower and the space more open” than with traditional media. Her colleague Mr. Hersman concurs. “Technology is one of the few ways that young Africans can bypass the inefficiencies in the system that allow the status quo to hold on,” he says. “It lowers the barriers to entry for everyone to get involved and be heard.”

From Kenya to the world

Since Ushahidi (which is also downloadable software) was designed to be used by ordinary people, allowing users to report an incident by filling in a very simple form with a description of what happened and when it took place, it has proven to be easily adaptable. The software has been used to help rescue victims in Haiti in the wake of a devastating earthquake in January. It has also been used to monitor violence in the DRC, South Africa and Gaza.

In addition, Ushahidi has helped people to use cell phones and the Internet to track the availability of medicines in pharmacies in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi and Zambia.

The platform allows ordinary people to report vote tallies as they are compiled. Cuidemos el Voto, an independent online mapping project in Mexico, used Ushahidi to monitor the last federal elections. So did Vote Report India, a collaborative citizen-driven election monitoring initiative, for the 2009 Indian general elections. Ironically, in February people in Washington, DC, the US capital, relied on the Kenyan software to help organize snow removal during a massive storm.

Revolutionary changes

Long before this latest trend, Africans have been using new technologies for various purposes with positive results, including in business, health care, distance learning and banking (see Africa Renewal, January 2008 and April 2008). According to the latest African Economic Outlook report of the industrialized countries’ Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the increasing use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Africa is helping to sustain parts of the African economy during these times of economic turbulence.

The recent use of such technologies in the political field is taking place amidst revolutionary technological changes across the continent. Africa’s mobile phone industry is growing at twice the global rate, according to the International Telecommunications Union. “The mobile phone, easy to carry around, and whose infrastructure is cheaper to deploy, has led Africa’s revolution,” adds the OECD report. As major undersea cables are being laid off the east and west coasts of the continent, broadband Internet access is also expected to vastly improve, a fact that prompts some to predict an end to the “digital divide” — the gap between those who have access to ICTs and those who do not.

Africa’s political bodies are striving to catch up. In late January an African Union (AU) summit took up the theme of ICT links to development. Earlier, in 2007, the continental body adopted a science and technology plan of action and asked the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to help. Talks are being held among the OECD, UNESCO and the World Bank, while UNESCO is supporting a review of science, technology and innovation in 20 African countries. Under the AU’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), all primary and secondary schools are to become “e-schools,” with computers, software and Internet access, by 2025 (see Africa Renewal, April 2007).

All these are welcome developments, notes Ushahidi’s Ms. Rotich. Africa, she concludes, “should invest in its brilliant minds and encourage its entrepreneurs.”

* Patrick Meier and Kate Brodock, “Crisis Mapping Kenya’s Election Violence: Comparing Mainstream News, Citizen Journalism and Ushahidi.” (Boston: Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Harvard University, 2008).